Source: Link

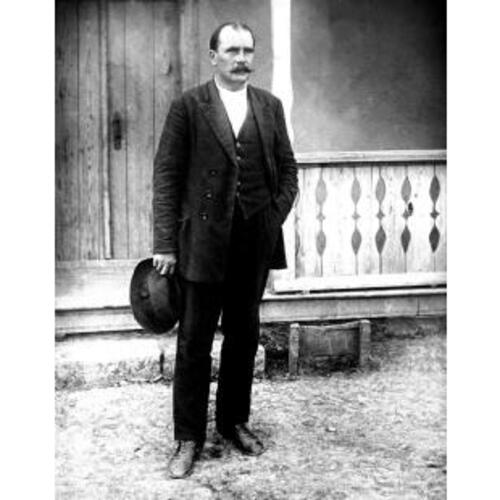

VERIGIN, PETER PETROVICH, Doukhobor leader; b. probably 2 Jan. 1881 in Slavianka (Azerbaijan), son of Peter Vasil’evich Verigin* and Evdokiia Grigor’evna Kotel’nikova; m. there Anna Fyodorovna Chernenkova (d. 1940), and they had a daughter and a son; d. 11 Feb. 1939 in Saskatoon.

Peter Petrovich Verigin was born into a Russian Christian sect, the Doukhobors [see P. V. Verigin], in inauspicious circumstances. His father had divorced his mother during her pregnancy on the instructions of the leader of the Doukhobor community in southern Russia, Luker’ia Vasil’evna Kalmykova, who wished to groom Peter Vasel’evich as her successor. Peter Petrovich was raised by his mother’s family, although his father provided some material support. As a young boy he was sent to boarding school in Elisavetpol (Gyandza, Azerbaijan), where he received excellent marks. He later studied at the Russian technical institute in Tiflis (Tbilisi, Georgia). Upon his return to Slavianka, he married Anna Fyodorovna Chernenkova, who came from a prominent family in the village.

Although a majority of Doukhobors – the group that would become known as the Large Party – acknowledged P. V. Verigin as leader several weeks after Kalmykova’s death in 1886, a minority, later known as the Smaller Party, rejected him. His opponents fought to have him arrested by tsarist authorities as a troublemaker, and the following January he was. When he was released in 1902 after 15 years of exile in northern and eastern Russia, he was allowed to join his followers in what would soon become Saskatchewan, where almost all of them had settled after emigrating in 1899; his son, however, was left behind in Russia. Peter Petrovich twice visited his father in Canada, in 1905 and probably in 1906, with the intention of immigrating along with a group of Russian Doukhobors. Relations were nonetheless strained, and the immigration plans were cancelled. Peter Vasel’evich was cool towards his son, who in turn publicly criticized and demeaned his father in front of his followers.

Within a year after returning from his first trip to Canada, the younger Verigin assumed leadership of the Vorobyov Doukhobors, also known as the Middle Party, in Transcaucasian Russia, and he weathered both local antagonisms and the vagaries of the Russian revolution. In 1921, at the behest of the Bolshevik government, he moved north with approximately 4,000 followers to the Sal’sk region, where he was recognized by Soviet authorities as the head of the collective farm that the settlers established there.

In late 1924 the senior Verigin died unexpectedly in a mysterious railway explosion in southeastern British Columbia. After his death the vast majority of Canadian Doukhobors invited Peter Petrovich to be their new leader. Although father and son had not gotten along, devotees of the former had heard that there was a family resemblance, and their choice was consistent with how leadership had most often been transmitted in the past. The federal Liberal government led by William Lyon Mackenzie King*, concerned about possible turmoil in the Doukhobor settlements, gave the invitation its blessing.

At the time, Canadian Doukhobors were divided over several issues. Their communal farming project, founded in the late 19th century on homesteads in what would become Saskatchewan in 1905, had taken a major blow that year when the federal minister of the interior, Frank Oliver, required homesteads to be registered individually. This action prompted Peter Vasil’evich, two years later, to lead the majority of Canadian Doukhobors to British Columbia, where he had been able to buy land for communal farming; this group, known as Community Doukhobors, would number about 6,000 after Peter Petrovich arrived in Canada in 1927. A minority of Doukhobors, however, refused to follow him and began to farm individually, mainly in Saskatchewan; they were known as Independents and numbered about 2,000 in 1927. There were also smaller Doukhobor populations in Alberta and Manitoba. Independents recoiled at the notion of a divine leader (a status that had been given to Peter Vasil’evich and was transferred to his son) and interacted more positively with outsiders than did others of the sect. Many Doukhobors were suspicious of public education, and efforts to improve school attendance had resulted in widespread absenteeism. A radical branch called the Freedomites (Svobodniki, later known as the Sons of Freedom), which probably totalled two dozen members in the mid 1920s, had been protesting the Community Doukhobors’ concessions with regard to public education [see Verigin] and their perceived materialism by appearing nude in public and burning down Community businesses, homes, and schools.

Peter Petrovich was aware of these issues when he accepted the invitation to be leader, and he gave an indication of his attitudes when he transmitted a message to Canadian Doukhobors instructing them to send their children to school. Shortly thereafter they held a meeting during which they announced their intention to respect Canadian institutions in the future. Verigin’s departure was delayed by his doubts about the move and his lengthy preparations, and then, more ominously, by his arrest and conviction before a Soviet workers’ court on charges of violence, habitual intoxication, extortion, and misuse of Community funds. He was stripped of his official leadership of the communal farm in the Sal’sk region, jailed for two years, and then slated to be exiled to central Asia. Verigin had a penchant for vodka and gambling and possessed a violent temper that periodically led him to get into physical fights with his followers as well as outsiders.

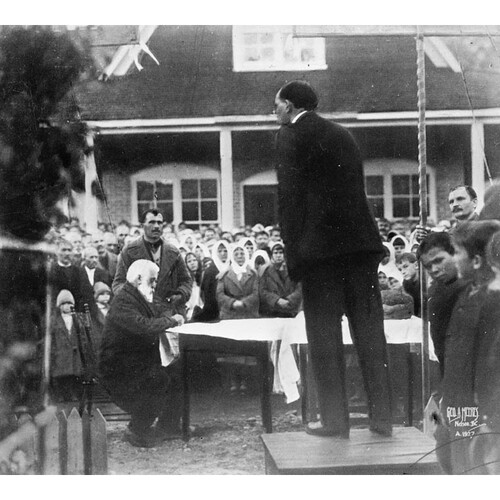

The Soviets, persuaded that Verigin was better banished from the country than sent into internal exile, permitted him to leave in September 1927. His wife and children remained behind. Canadian Doukhobors had sent him thousands of dollars, nearly all of which was spent by the time he departed. When he landed in New York, he was met by Michael Cazakoff, the acting chairman of the Christian Community of Universal Brotherhood (CCUB), which was the Community Doukhobors’ corporation and the official name of the Doukhobor organization in Canada. On his arrival in Canada he made a positive impression on federal politicians and the press, stressing the need for good relations with Canadians and their government while exhorting Doukhobors to preserve their culture and the Russian language. He visited Ottawa and Winnipeg, and then Doukhobor communities in Yorkton and Veregin, Sask., where he gave a speech reclaiming unity, thus revealing himself to be a good orator with a certain philosophical depth. It is then that he gave himself the name Chistiakov (meaning “the purger” or “the cleanser”). He toured settlements in Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta before travelling to British Columbia to visit Nelson and then Brilliant, the primary Community settlement. The more mercurial side of his character rapidly became evident as he engaged in verbal attacks on the officers of the CCUB for their alleged mismanagement of communal funds, arrived late at meetings, and gave way to violent outbursts of anger. His propensities to excessive drinking and gambling were noted. Many believed, however, that their leader was semi-divine, so they accepted his injunction “Don’t do as I do, but as I say” and his excuse that if he were to live a good religious life, he would be killed by the government like Christ.

Early on, Verigin was vigorous in addressing the economic and social problems facing the Doukhobors. Through reorganization of CCUB finances, improved bookkeeping, and appeals to the faithful, he was able to decrease the debt. To encourage his followers to take more economic initiatives, he decentralized the commune system established by his father, dividing Community Doukhobors into smaller groups (around 25 to 100 people), which he called Families, who were located on communal property in British Columbia, Saskatchewan, and Alberta. He also got rid of the barter system established by his father. Henceforth, Families were to direct payments to the central coffers, in amounts proportionate to their population or the acreage of their settlement.

The unity achieved by Verigin was evident in the 1928 establishment of the Society of Named Doukhobors, which had members in all four western provinces. The organization adopted a set of resolutions called the Protocol, which adhered to the teachings of Christ, non-violence, marriage based on love, support of public education, peaceful internal resolution of disputes, and expulsion of criminal offenders. He had Community homes built in Saskatchewan and British Columbia among Independent settlements, established regional libraries, and in 1932 formed the first Doukhobor youth organization. Verigin’s initial apparent public approval of the Freedomites as “the ringing bells” (by which he meant the conscience) of Doukhoborism, had been delivered in a speech at Brilliant in 1927 (during which he had coined the designation Sons of Freedom). Verigin’s approval of the group was short-lived, however, because they increasingly believed that his meaning was the opposite of what he stated. Thinking that his instructions were a test of their allegiance, many responded by acting against them. In 1929 Verigin spoke of a plan to lead Doukhobors out of Canada on a “white horse,” eventually selecting Mexico as their destination. Although the scheme came to nothing, by 1932 he had raised over half a million dollars from lenders, most of which was never repaid, and he personally profited by about $46,000, having lent out the capital and charged interest.

From 1929 the torching of schools and nude protests by the Sons of Freedom, and Verigin’s seemingly benign contact with the group (in fact, he denounced their actions and expelled them from Community land), had generated the belief in the outside world that he was both their closet leader and a Bolshevik provocateur. Undercover work and speculation by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police was crucial to the development of these ideas in the Conservative governments of Richard Bedford Bennett* in Ottawa, James Thomas Milton Anderson* in Regina, and Simon Fraser Tolmie in Victoria. They made plans to move against the radical Sons of Freedom and deport the man considered to be leader. In 1931 the federal government, under pressure from the provinces, increased the penalty for appearing nude in public, thus allowing British Columbia to proceed the following spring with mass arrests of nude adult Doukhobors and the seizure of their children for re-education.

Verigin fell into the hands of government authorities by perjuring himself in litigation over a land dispute with a Doukhobor in Saskatchewan. He was found guilty in 1932 and received a prison term of three years. At the end of January 1933, nine months into his sentence, Ottawa quietly granted him clemency, and two immigration officers rearrested him on a deportation charge. They moved him from Prince Albert, Sask., to Halifax, where he was to be sent back to the Soviet Union. This attempt and another in Winnipeg in early June were thwarted, however, by his shrewd lawyers and by incompetent immigration officials. No further attempt was made to remove him since a Soviet diplomat sent the message to Canadian authorities in June that his country had no intention of allowing him back in, and because Verigin acquired permanent residency status in Canada the following month.

Although Peter Petrovich had eluded deportation, his leadership of Canadian Doukhobors was in tatters. The CCUB was still burdened with debt: the number of members had decreased from 5,485 in 1928 to 3,103 in 1937, and only about two-thirds of them had paid their fees. Cumulative losses due to incendiarism were estimated at over $437,000 that year. Verigin had nonetheless managed to reduce by more than half the $1.2 million debt left by his father, but it was not enough to satisfy creditors. In 1937 mortgage companies moved to foreclose on loans, and the Independents left the Society of Named Doukhobors. The Sons of Freedom, many of whom had served prison terms for public nudity and whose ranks had increased in number because of disaffection among Community Doukhobors, were already following their own program. Verigin himself was thrice convicted, either of assault or drunk and disorderly behaviour.

Peter Petrovich Verigin died of liver and stomach cancer in Saskatoon in 1939 and was buried beside his father at the Verigin Memorial Park in Brilliant. A few weeks later Verigin’s son in the Soviet Union, Peter Petrovich Jr (known as Iastrebov, meaning “the hawk”), was chosen as leader. Peter Petrovich Verigin Sr’s grandson, John J. Verigin*, who had immigrated to Canada in 1928, was selected as secretary of the Union of Spiritual Communities of Christ, which had succeeded the CCUB in 1938. The death of the Canadian Doukhobors’ second leader was to be the harbinger of increased turmoil within the organization and between its more radical elements on the one hand and the state and non-Doukhobors in British Columbia on the other.

Peter Petrovich Verigin’s birth record has not been found and his birth year varies in secondary sources. The probable birth date of 2 Jan. 1881 comes from the Canadian Doukhobors’ website: Union of Spiritual Communities of Christ – Doukhobors, “Verigin Memorial Park – Castlegar”: usccdoukhobors.org/veriginpark/veriginpark.htm (consulted 19 Sept. 2018). For the overall history of the Doukhobor community and relations with the non-Doukhobor world, see George Woodcock and Ivan Avakumovic, The Doukhobors (Toronto, 1968; repr. Ottawa, 1977); K. J. Tarasoff, In search of brotherhood: a history of the Doukhobors (Vancouver, 1963) and Plakun trava [Willow-herb]: the Doukhobors (Grand Forks, B.C., 1982); and A. B. Androsoff, “Spirit wrestling: identity conflict and the Canadian ‘Doukhobor problem,’ 1899–1999” (phd thesis, Univ. of Toronto, 2011). Plakun trava includes excellent photos from Tarasoff’s extensive collection, which is now held at the BCA (PR-0137). For insights into Verigin’s life and times written in Russian and translated into English, see A. P. Markova, “A biography of Peter Petrovitch Verigin-Chistiakov,” in Summarized report: Joint Doukhobor Research Committee symposium meetings, 1974–1982, comp. and trans. E. A. Popoff ([Castlegar, B.C., 1997]), 253–65 (Markova was Verigin’s daughter). Also useful is Kathy Morell, “People and places: the life of Peter P. Verigin,” Saskatchewan Hist. (Saskatoon), 61 (2009), no.1: 26–32. On Verigin’s stormy life in Canada, see LAC, RG76-B-1-a, vol.739, file 527744 (Veregin [sic], Peter (the younger), Doukhobor leader), and J. [P. S.] McLaren, “Wrestling spirits: the strange case of Peter Verigin II,” Canadian Ethnic Studies (Calgary), 27 (1995), no.3: 95–130. The history and outlook of the Sons of Freedom are addressed in J. C. Yerbury, “The ‘Sons of Freedom’ Doukhobors and the Canadian state,” Canadian Ethnic Studies, 16 (1984), no.2: 47–70.

Winnipeg Free Press, 11 Feb. 1939. Yorkton Enterprise (Yorkton, Sask.), 20 Nov. 1931; 2 Feb., 10 May 1932.

Cite This Article

In collaboration with John P. S. McLaren, “VERIGIN, PETER PETROVICH,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 30, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/verigin_peter_petrovich_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/verigin_peter_petrovich_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | In collaboration with John P. S. McLaren |

| Title of Article: | VERIGIN, PETER PETROVICH |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2022 |

| Year of revision: | 2022 |

| Access Date: | December 30, 2025 |