BROWN, ERIC, office holder, arts administrator, author, lecturer, and farmer; b. August 1877 in Nottingham, England, one of the nine children of John Henry Brown and Emma Wardle; m. 25 Dec. 1910 Florence Maud Sturton in Toronto; they had no children; d. 6 April 1939 in Ottawa.

Eric Brown’s father was a Nottingham city councillor; his mother died when he was four. A sports injury interrupted his education at Nottingham High School by requiring a prolonged convalescence, during which he read voraciously and converted to Christian Science. Both reading and Christian Science would be lifelong passions, the latter helping to shape his conviction that art needed to be morally improving. Forgoing university, Eric trained as an artist with his elder brother, the landscape painter Arnesby Brown; grew cotton with a cousin on the island of Nevis in the West Indies; and farmed in Lincolnshire. While in Lincolnshire he became engaged to Maud Sturton, who had been educated at the women-only Newnham College (officially affiliated with the University of Cambridge in 1948), despite her family’s objections about his apparently dismal career prospects.

Around 1909 Arnesby introduced Eric to Montreal art dealer Frank Robert Heaton, who convinced him that an ambitious Englishman could thrive in Canada’s inchoate arts community. In Maud’s words, Heaton’s intervention was “an answer to prayer.” On his arrival in Canada shortly thereafter, Brown worked initially in Montreal, taking care of an exhibit of British paintings on loan, and then went to the Art Museum of Toronto, where he was in regular contact with banker and collector Byron Edmund Walker*. In June 1910 Walker became chair of the Advisory Arts Council [see Sydney Arthur Fisher*], which oversaw the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa. He arranged for Brown’s September appointment as the institution’s first full-time curator, one of the very few salaried arts posts in Canada. (The part-time curators who preceded him, John William Hurrell Watts* and Lawrence Fennings Taylor, had been architects in the Department of Public Works.) Financial stability enabled Brown to marry Maud, who was teaching in Toronto. Theirs was a devoted personal and professional alliance, based on shared religious faith (Maud was also a committed Christian Scientist), interests, and values.

Brown took over a 30-year-old gallery that was located in a federal-government building devoted to fisheries and administered by the Department of Public Works. Years later, Brown would tell the story that, not long after he became curator, a small boy asked him, “Say, Mister, where’s the whale?” The gallery had no national profile, a small staff, a minuscule budget, and an unremarkable collection. In 1912 it moved into a wing of the new Victoria Memorial Museum, and Brown helped draft the National Gallery of Canada Act, which made it an independent institution in June of the following year. He was now the gallery’s director, with a budget in 1915 of $100,000, most of which was spent on art. This budget shrank dramatically over the course of World War I and was rarely as generous again. Brown’s greatest legacy is the collection he assembled within these financial constraints, initially in close collaboration with Walker. Convinced that “no country can be a great nation until it has great art,” Brown aimed to accumulate the finest possible collection of European paintings and the most complete representative collection of Canadian ones. He and Walker regularly visited European dealers and collectors and used advisers to find affordable old masters as their prices rose sharply after the war. In the 1920s they acquired the works produced under Canada’s war-art program (formally known as the Canadian War Memorials Fund), amassed prints and drawings, and founded the sculpture collection.

Brown also greatly influenced the evolution of Canadian art by befriending, encouraging, and championing contemporaries such as Thomas John (Tom) Thomson*, the members of the Group of Seven, and Emily Carr*. Many critics treated this new generation of artists with derision; for example, Hector Willoughby Charlesworth*, preferring the work of more traditional painters such as Mary Augusta Catharine Reid [Hiester*] and Carl Henry Ahrens, dismissed them as painters of “inferior quality” lacking in “aesthetic sensibility”; and Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King* described their art as a “perversion.” Brown disagreed. He was convinced that, by “believing in and understanding Canada,” these artists were creating a uniquely Canadian idiom. As he wrote in 1913, “a national spirit is being slowly born.… There are painters who are finding expression of their thought in the vast prairies of the far West, in the silent spaces of the North, by the side of torrent and tarn, and in the mighty solitudes of the winter woods.”

The gallery first purchased canvases by future members of the Group of Seven in 1912, eight years before the group’s formation, and added Thomson’s Northern river in 1915. Brown remained an enthusiastic supporter of the Group of Seven in the years afterwards, including their work in the collection of Canadian art displayed at the British empire exhibitions in Wembley (London), England, in 1924 and 1925, and at the Musée du Jeu-de-Paume in Paris two years later, the first showings of the group’s paintings outside Canada. As for Carr, Brown first met her in Victoria in 1927. According to her own account, which was more dramatic than accurate, she had long since given up painting in frustration. Brown persuaded her to contribute to a gallery exhibition, purchased three canvases, and motivated her to paint again. Carr’s presence in the collection cemented the gallery’s national reach, and after Brown’s death, she attested to his inspirational qualities in a letter to Maud, saying that he “saved me from being a quitter.” She also wrote, “I owe him so much for I was overwhelmed by despair about my work when he came west and pulled me out and made me start again.”

Brown’s promotion of his favourites in exhibitions, lectures, and articles sometimes caused tension with the gallery trustees, while artists working in more traditional styles felt marginalized. In 1932 over 100 artists, led by Edmund Wyly Grier* (who had been the best man at Brown’s wedding) and reflecting the conservative instincts of the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts, petitioned the government of Richard Bedford Bennett* to dismiss Brown. This effort prompted more than 300 other artists, including Alexander Young Jackson*, to come to Brown’s defence. Thereafter, his authority was unassailable.

Brown was an indefatigable proselytizer who saw the gallery as a tool for stirring Canadians out of an ingrained apathy towards the arts. Maud led tours of the collection; Saturday mornings were reserved for children; and the doors were unlocked on Sundays, a Canadian first for an art gallery. Further evidence of Brown’s innovative approach occurred when a fire destroyed the centre block of the Parliament Buildings in February 1916. With mps and senators taking over the Victoria Memorial Museum, the gallery found itself without a home for five years, but Brown saw this development as an opportunity to extend the institution’s influence through loans, travelling exhibitions, and lectures that he, Maud, and others delivered throughout the country. He also organized annual exhibitions of Canadian art, sent colour reproductions to schools, circulated lantern slides and art films, trained gallery professionals, and awarded scholarships. He published catalogues of the collection and pioneering essays on Canadian art history, and gave groundbreaking lectures on the radio service of the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation and the television arm of the British Broadcasting Corporation. Many ventures were funded by the American Carnegie and Rockefeller foundations, with which Brown and his assistant Harry Orr McCurry began working in the late 1920s because they understood the importance of this financing at a time when no comparable Canadian sources existed. Brown capped his career in 1938 with a retrospective exhibition, A century of Canadian art, at London’s Tate Gallery.

Brown’s peers elected him president of the Association of Art Museum Directors and vice-president of the Museums Association of Great Britain. He was an honorary member of the Royal Scottish Society of Painters in Watercolours and received the King George V Silver Jubilee Medal (1935) and the King George VI Coronation Medal (1937). Yet for all his accomplishments, Brown failed in two notable ways. First, his support for contemporary Canadian artists was accompanied by a conservative, and sometimes complete, disdain for influential international art movements such as Post-Impressionism, Futurism, and Cubism. The gallery began acquiring paintings in these genres after his death, at vastly higher prices. Secondly, despite Brown’s continuous lobbying, his goal of a permanent, purpose-built national gallery was not achieved until long after his time, when the doors of the building designed by Moshe Safdie were opened in 1988.

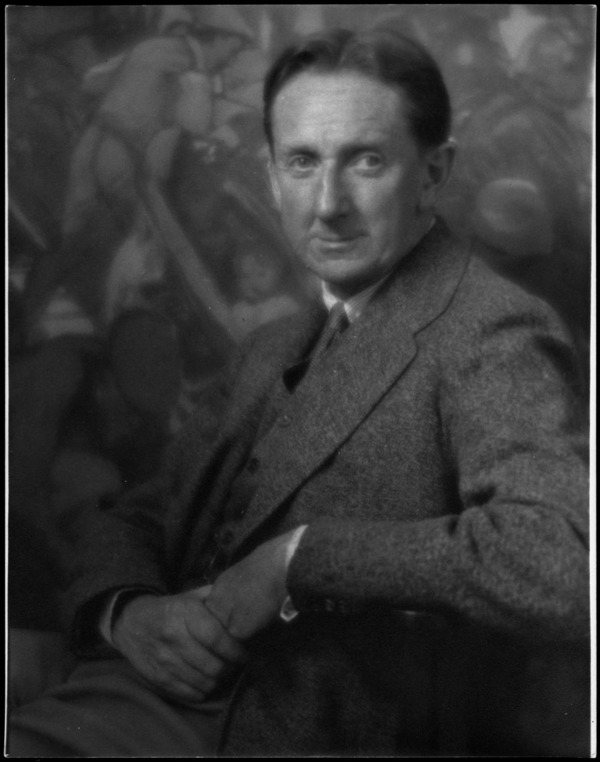

Brown was a tall, slim man with a prominent nose who dressed elegantly and sported a monocle, an improbably British appearance for Canadian art’s champion. However, he and Maud were deeply attached to Canada. Unpretentious, warm, witty, and urbane, they shared a love of hiking, canoeing, camping, and skiing with many of the country’s younger artists and were active in Ottawa’s theatre scene. Friends from the arts world and beyond regularly gathered at their home at 657 Echo Drive, where Brown died after a brief illness. He was interred at Beechwood Cemetery. He had turned the gallery into a truly national institution and his favoured artists into Canadian icons.

Eric Brown is the author of “Canada and her art,” American Academy of Political and Social Science, Annals (Philadelphia), 45 (January 1913): 171–76. He and his wife, Maud, left no correspondence and very few papers giving details of their private lives; consequently, such details as presented here are gleaned mostly from her short biography of him, entitled Breaking barriers: Eric Brown and the National Gallery ([Ottawa, 1964]). Eric Brown’s precise date of birth is not entirely clear. In his civil-service personnel file, which is held in the Library & Arch. of the National Gallery of Can. (Ottawa), PC 105/1133, he states that it is 1878 – without indicating a month or day. However, his wife’s biography and his tombstone (an image is available on Ancestry.com, “Ottawa, Canada, Beechwood Cemetery registers, 1873–1990,” Eric Brown: www.ancestry.ca (consulted 8 May 2017)) indicate 1877 as the year of his birth; the author considers these sources to be more authoritative than the personal record.

The National Gallery collection includes several portraits of Brown. There are also a number of photographs of him held at LAC.

LAC, “Diaries of William Lyon Mackenzie King,” 14 April 1934: www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/discover/politics-government/prime-ministers/william-lyon-mackenzie-king/Pages/diaries-william-lyon-mackenzie-king.aspx (consulted 8 May 2017); R2336-0-6. National Gallery of Can., Library & Arch., Eric and Maud Brown fonds. Univ. of Toronto Libraries, Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, ms coll. 1 (Sir Edmund Walker papers). Ottawa Evening Journal, 6 April 1939: 1, 12. J. S. Boggs, The National Gallery of Canada (Toronto, 1971). J. D. Brison, Rockefeller, Carnegie, and Canada: American philanthropy and the arts and letters in Canada (Montreal and Kingston, Ont., 2005). F. M. Brown, “Eric Brown: his contribution to the National Gallery,” Canadian Art (Ottawa), 4 (November 1946–summer 1947): 8–15, 32–33. Emily Carr, Growing pains: the autobiography of Emily Carr (Toronto, 1946). H. W. Charlesworth, “The National Gallery a national reproach: many fine British and French works, but selections in Canadian section away below standard,” Saturday Night, 9 Dec. 1922: 3. W. G. Constable, “Eric Brown as I knew him,” Canadian Art, 10 (autumn 1952–summer 1953): 114–19. Ross King, Defiant spirits: the modernist revolution of the Group of Seven (Kleinburg, Ont., 2010). National Gallery of Can., Annual report (Ottawa), 1920/21–1939/40. Douglas Ord, The National Gallery of Canada: ideas, art, architecture (Montreal and Kingston, Ont., 2003). Tate Gallery, A century of Canadian art: catalogue (London, 1938).

Cite This Article

Andrew Horrall, “BROWN, ERIC,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 30, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/brown_eric_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/brown_eric_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Andrew Horrall |

| Title of Article: | BROWN, ERIC |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2020 |

| Year of revision: | 2020 |

| Access Date: | December 30, 2025 |