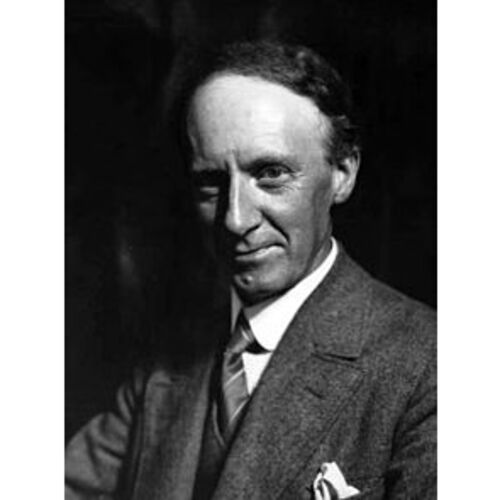

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

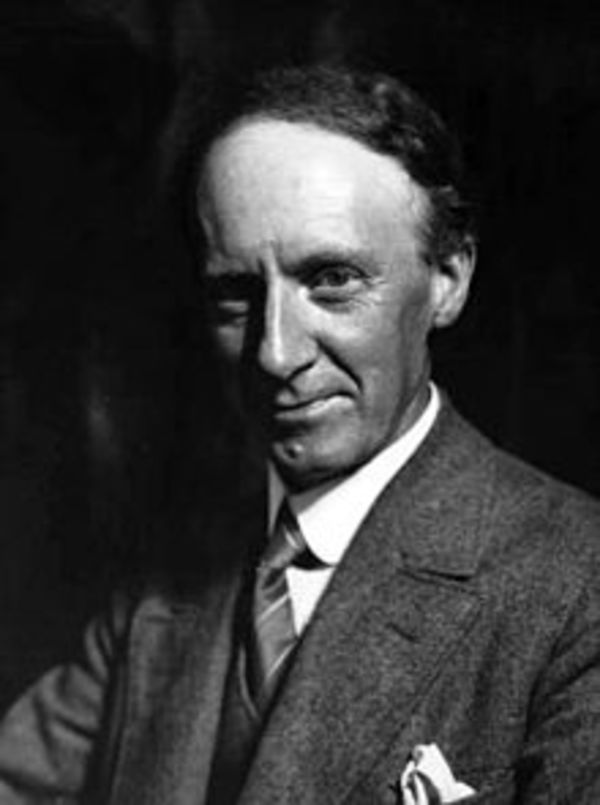

MacDONALD, James Edward Hervey (Harvey), artist, educator, and author; b. 12 May 1873 in Durham, England, son of William Henry MacDonald, a cabinetmaker, and Margaret Usher (Ussher); m. 12 May 1899 Harriet Joan Prior Lavis (named Harriet Joanna Dionysius Lavis at birth; 1871–1962) in Swansea (Toronto), and they had one son, Thoreau*; d. 26 Nov. 1932 in Toronto.

J. E. H. MacDonald was a critical force behind the formation in 1920 of the Group of Seven, the Toronto-based painters who gave Canada a visual identity to accompany its birth as a nation in the years leading up to and the decade and a half following the First World War. Since he was the eldest by about ten years of the members of this creative circle (except for Thomas John (Tom) Thomson*, who died in 1917 before the group was formally established), he had a degree of authority by default. More telling were his varied talents as painter, designer, teacher, poet, writer, administrator, and aesthetic trailblazer, which made him their spiritual leader: no one else had as strong and lasting an influence on Canada’s major artists of the period.

MacDonald’s importance was due to his deep involvement as a teacher of and mentor to practitioners of both commercial and fine art. Commercial art was a huge part of his life, but he was able to separate it from his work as an artist who broke conventions, took risks, and led innovation by example. When his bold and inventive paintings were attacked by critics, he batted back their gibes with witty and trenchant arguments that were widely published.

A tall, lean, and somewhat frail man with slightly wavy, reddish hair, he was sensitive, almost delicate, capable, and possessed of a buoyant sense of humour. He was intensely curious about everything – industry, agriculture, gardening, construction, wilderness, and fishing. He was not, however, adept at paddling, camping, or other so-called manly activities. An early biographer, art curator Edmund Robert Hunter, wrote in 1940: “He held that life was all of a piece, and the duty of every man was to understand it, find his right place in it, and be useful and happy. The tyranny of tradition in art or in any other form repelled him.… He despised humbug, the charlatan, the poseur, the go-getter, the coward, the man who grovelled, and dismissed them with contempt. Of formal religion he had none.… His religion resembles that of [poet Robert] Burns in his passion for decency, kindness, and justice.” Surrounded as he was by colleagues in thrall to transcendentalists Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau – he named his only child after Thoreau – and by intense theosophists (Lawren Stewart Harris* particularly), and being himself an admirer of Walt Whitman, MacDonald became a proponent of a gentle spiritualism based on these sources.

Born in England to a Canadian father and an English mother who moved the family to Canada when James was nearly 14, he lived first in Hamilton, where he attended night classes at the Hamilton Art School, and then in Toronto. He was apprenticed at the Toronto Lithographing Company and on evenings and weekends frequented the Central Ontario School of Art and Design. In 1894 he took his abilities to Grip Printing and Publishing Company (from 1901 Grip Limited), a commercial art and engraving firm.

He went back to England in 1903 to work for London’s renowned Carlton Studio, a design firm established by Canadian friends, before returning four years later to Grip Limited as head designer. One of the first men subsequently hired was Tom Thomson, in whom MacDonald recognized a latent talent. Before MacDonald left the company in 1911 to paint full time, encouraged to do so by Harris and art patron Dr James Metcalfe MacCallum, the firm had taken on Arthur Lismer*, Franklin Carmichael*, and Francis Hans (Frank) Johnston*; Frederick Horsman Varley* began work at Grip just as MacDonald departed. The latter artists were a mere few years, and a horrific war, away from forming the Group of Seven.

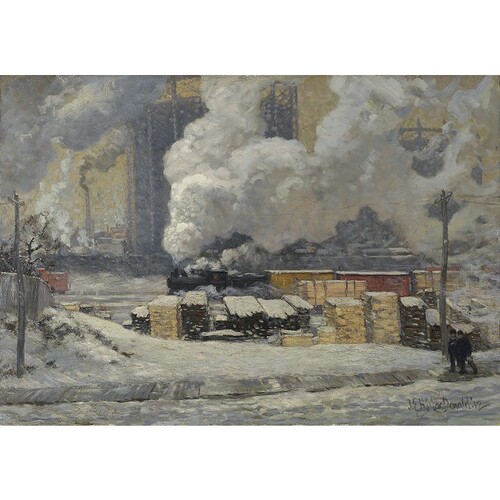

In 1911 MacDonald was made a member of the Arts and Letters Club, where in November that year he had his first one-man show, an exhibition of small oil sketches of subjects in Toronto and vicinity, including the city’s High Park, close to his home. Harris and landscapist Charles William Jefferys* were immediately excited by the originality of his work: it was “as native as the rocks, or the snow, or pine trees, or … the lumber drives that are so largely his themes,” Jefferys wrote in the club magazine, and rare in “a country so provincial and imitative in its tastes.”

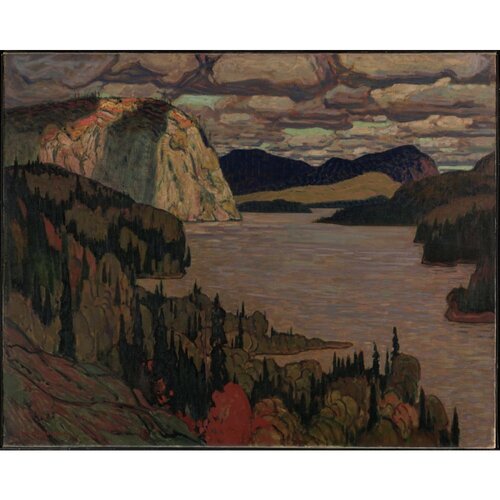

MacDonald painted urban locales in Toronto with Harris. Harris also took him on sketching trips to the Laurentians, the Gatineau hills, Algoma, Lake Superior, and finally, in 1924, the Rocky Mountains, which became MacDonald’s summer retreat for another six years; MacDonald would paint at Lake Simcoe, Georgian Bay, and Algonquin Park as well, and in Nova Scotia. Although his health was never robust, he managed to pack in over 20 sketching trips to various parts of Canada; he painted in Barbados as well while recovering from illness. A defining moment occurred in 1913, when MacDonald and Harris saw an exhibition of contemporary Scandinavian painters at the Albright Art Gallery in Buffalo, N.Y. The way those artists painted their landscapes, which featured a terrain similar to Canada’s, was a revelation. MacDonald described his and Harris’s reaction: “It seemed an art of the soil and woods and waters and rock and sky.… It was this song of praise to their countries that captured our susceptible Canadian souls.” The experience spurred MacDonald and Harris to urge Canadian artists to tackle their own country’s geography with equal ambition and originality. This mission was stalled by the war in Europe, but the revelation was a lasting stimulus. In Toronto, Harris and Dr MacCallum erected the Studio Building, which opened in 1914 and provided six professional spaces to encourage full-time painting by MacDonald, Thomson, Alexander Young Jackson*, and others. The Group of Seven held its first exhibition in May 1920 (works by the late Tom Thomson and others were included). It is likely that MacDonald and Harris had chosen the painters invited to join the group. Over time, as more artists became associated with the original members and some turned to abstraction, MacDonald began to feel that standards were not being maintained. The group would hold its last exhibition in 1932.

Like most of his fellow artists, MacDonald was unable to make a living by painting alone; most of the work he sold went to public museums, including the National Gallery of Canada, where curator Eric Brown was a firm supporter. Over the years he continued his commercial work on a commission basis, producing magazine and catalogue illustrations, book decoration (often at the invitation of publishers John McClelland* and Lorne Albert Pierce*), and stage-set designs, as well as posters (among them war posters), advertisements, bookplates, memorial plaques, and similar items. For a number of years he was an instructor – along with John William Beatty* and others – for the Shaw Correspondence School, and he taught at summer schools held by the Ontario Society of Artists and the Ontario College of Art. Active as a lecturer, he also contributed articles and poetry to such journals as the Canadian Forum (Toronto). He returned to a full-time job in 1921, joining the staff of the Ontario College of Art. A popular and able teacher, he was made head of the department of graphic and commercial art six years later. In 1929 he took on the principalship as well, in succession to George Agnew Reid*. His classroom and administrative work were heavy since he never refused a responsibility; he became one of the college’s great principals.

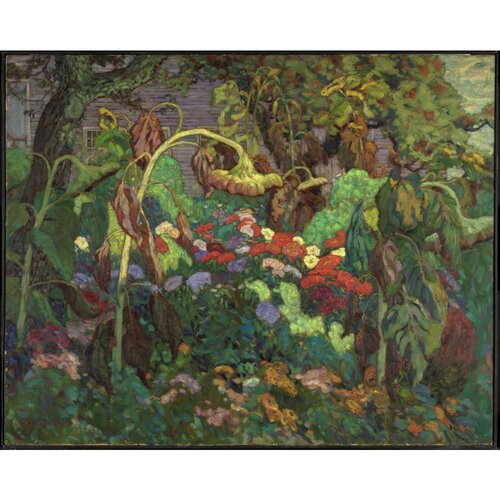

During the course of his career MacDonald painted between 600 and 800 oil sketches and 150 canvases. His major works include Tracks and traffic and The elements (1912 and 1916; both held by the Art Gallery of Ontario), Laurentian hills (1914; private collection), The tangled garden and The solemn land (1916 and 1921; National Gallery of Canada), Church by the sea (1924; Vancouver Art Gallery), and Rain in the mountains (1924; Art Gallery of Hamilton). In 1915–16, with Thomson and Lismer, he planned and executed wonderful decorative panels for Dr MacCallum’s Georgian Bay cottage (now in the National Gallery of Canada). Another of his great achievements was designing the artwork for the domed chancel of St Anne’s Anglican Church in Toronto in 1923. To complete the murals and other embellishments, he assembled a team of nine additional artists, including two fellow members of the Group of Seven (Varley and Carmichael) and sculptors Frances Loring* and Florence Wyle*. The church is now a national historic site.

Ill health dogged MacDonald most of his adult life. He often worked when he should have been resting. In 1917 he suffered a collapse under the strain of his difficult financial circumstances, his distress over the death of Tom Thomson, and his revulsion against the continuing slaughter in Europe. Recovery from a stroke in late 1931 was the occasion of his trip to Barbados. He died in 1932 following a severe stroke. He had been a member of the Ontario Society of Artists from 1909 and an associate of the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts from 1912 until the RCA, belatedly, made him a full academician in 1931, when he was 58.

For a lecture in 1930 he had written, “Art is the successful communication of a valuable experience.” An essay by Dr Shirley Lavinia Thomson [Cull*] on MacDonald for the Thomson Collection at the Art Gallery of Ontario concludes that he had achieved this goal: “The Canadian public still responds to the brilliance of his colour, the vigour of his compositions and the rich variety of his landscapes.”

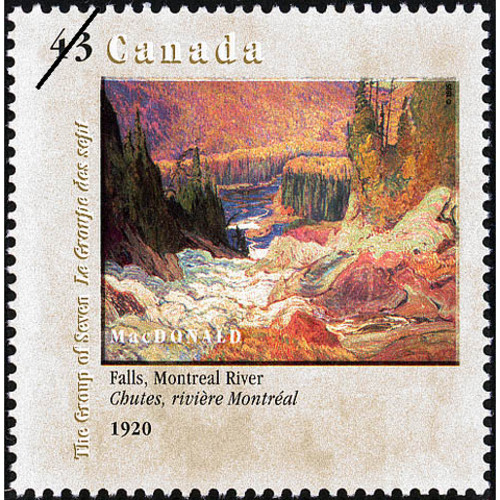

James Edward Hervey MacDonald published four books of poetry: The manger (n.p., n.d.); Village & fields: a few country poems (Thornhill, Ont., 1933); West by east and other poems (Toronto, 1933); and My high horse: a mountain memory ([Thornhill], 1934). One of his paintings, Mist fantasy, northland (1922; Art Gallery of Ont.), formed the basis of a stamp issued by Canada Post in 1973, and another, Falls, Montreal River (1920; Art Gallery of Ont.), was reproduced in 1995 as part of a series featuring the original and three later members of the Group of Seven. In 2013 the Royal Canadian Mint issued, in its Group of Seven series, a $20 silver coin bearing an image of MacDonald’s decorative panel Sumacs, painted for Dr McCallum’s cottage. In May 2020 the Group of Seven was recognized in a set of stamps on the 100th anniversary of its first exhibition; MacDonald is represented by a reproduction of The church by the sea. Early in 2015 it was announced that previously unknown works by MacDonald had been identified in a private collection. These items, said to have been buried in 1931 on a property the artist had purchased in Thornhill and not retrieved until 1974, were acquired by the Vancouver Art Gallery, and some were sent to the Canadian Conservation Instit. in Ottawa for authentication. Its report, delivered in September 2016, has not been made public and the gallery has not commented on it. In using the spelling Hervey for MacDonald’s third given name, this biography follows that written by E. R. Hunter (infra), who was his student and knew him well. It may well be that Hervey was MacDonald’s own preference. It should be noted, however, that Harvey appears in his christening, marriage, and death records. See FamilySearch, “England births and christenings, 1538–1975”: www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:NJJQ-SZ6; “Ontario deaths, 1869–1937 and overseas deaths, 1939–1947”: www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:JKHC-W43; and “Ontario marriages, 1869–1927”: www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:KZBH-VCW (consulted 9 July 2020).

Lisa Christensen, The Lake O’Hara art of J. E. H. Macdonald and hiker’s guide (Calgary, 2003). I. A. C. Dejardin et al., Painting Canada: Tom Thomson and the Group of Seven (exhibition catalogue, Dulwich Picture Gallery, London, 2011). E. R. Hunter, J. E. H. MacDonald: a biography & catalogue of his work (Toronto, 1940). J. E. H. MacDonald and Paul Duval, The tangled garden (Toronto, 1978). Marylin McKay, “St. Anne’s Anglican Church, Toronto: Byzantium versus modernity,” Journal of Canadian Art Hist. (Montreal), 18 (1997): 6–27. [N. E. Robertson], J. E. H. MacDonald, R.C.A., 1873–1932 (exhibition catalogue, Art Gallery of Toronto [Art Gallery of Ont.] and National Gallery of Can., [Toronto?, 1965]). D. P. Silcox, The Group of Seven and Tom Thomson (Toronto, 2003; subsequent eds., Richmond Hill, Ont., 2006 and 2011). Robert Stacey, J. E. H. MacDonald, designer: an anthology of graphic design, illustration and lettering ([Ottawa], 1996). S. L. Thomson, “J. E. H. MacDonald,” in J. E. Adamson et al., Canadian art: the Thomson Collection at the Art Gallery of Ontario ([Toronto and Seattle, Wash.], 2008). Bruce Whiteman, J. E. H. MacDonald (Kingston, Ont., 1995)

Cite This Article

David P. Silcox, “MacDONALD, JAMES EDWARD HERVEY (Harvey),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 30, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/macdonald_james_edward_hervey_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/macdonald_james_edward_hervey_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | David P. Silcox |

| Title of Article: | MacDONALD, JAMES EDWARD HERVEY (Harvey) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 2023 |

| Access Date: | April 30, 2025 |