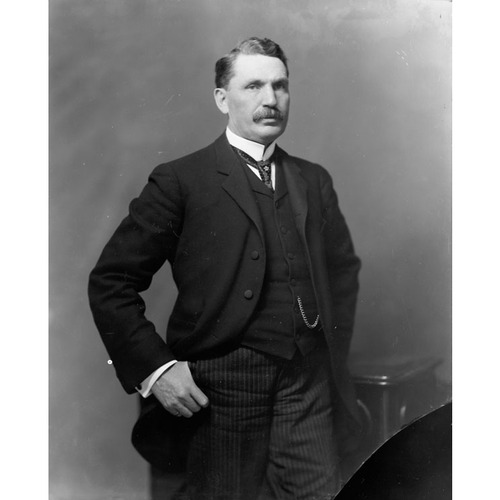

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

AHEARN, THOMAS, telegraph operator, electrical engineer, inventor, industrialist, and office holder; b. 24 June 1855 in Ottawa, son of John Ahearn, a blacksmith, and Honorah Power; m. there first 25 June 1884 Lilias MacKey Fleck (d. 22 Aug. 1888 in childbirth), and they had a son, future mp Thomas Franklin, and a daughter, Lilias, who would marry publisher Harry Stevenson Southam*; m. there secondly 16 Dec. 1892 his first wife’s sister Margaret Howett Fleck (d. 3 Jan. 1915); they had no children; d. there 28 June 1938.

Thomas Ahearn grew up in Le Breton (LeBreton) Flats, then a working-class neighbourhood of Ottawa, in a family of Irish Catholic immigrants. He attended the College of Ottawa, but he was expelled for misbehaviour and did not complete his formal education. He would go back to school in his seventies to be officially certified as a telegraph and telephone operator. In 1868 Ahearn started work as a messenger at the Chaudière (Ottawa) office of the Montreal Telegraph Company, and in 1873 he moved to New York, where he was employed as an operator in the head office of the Western Union Telegraph Company. This post exposed him to the best management strategies and technologies in the field. Two years later he returned to Ottawa and was appointed the chief operator of the Great North Western Telegraph Company of Canada.

The big break for Ahearn came in 1879 when, together with his friend and business partner Warren Young Soper, he won a contract to install telegraph sets across the country for the Canadian Pacific Railway. The contract provided them with enough capital to form an electrical-consulting company, Ahearn and Soper, in 1882. The following year the young men were awarded a contract to introduce electric lights into the House of Commons. The lights were switched on in January 1884, a full year earlier than at the Capitol in Washington, D.C. In 1887 Ahearn and Soper, who now represented the Westinghouse Electric Company in Canada, incorporated the Chaudière Electric Light and Power Company under a federal charter, which allowed them to conduct business in both Ottawa and Hull (Gatineau), Que. Through his connections to Westinghouse, Ahearn was familiar with the newest technical developments in power generation. Unlike other companies in the field, Chaudière Electric Light and Power invested in an incandescent, alternating-current system, then still experimental and virtually unknown in Canada.

Ahearn’s companies grew faster than the others in the city; he had the most clients and the best technologies. By 1895 he and Soper had built an empire in Ottawa. They owned Ahearn and Soper, which made control equipment and small electric appliances and distributed Westinghouse products in Ontario; as well, they ran the Ottawa offices of the Bell Telephone Company of Canada and controlled Chaudière Electric Light and Power. In 1891, after Ahearn and Soper had won a city contract to install an electric-powered transit service, the partners established the Ottawa Electric Street Railway, the first such system in Canada to offer a winter service. They also acquired majority ownership in the older Ottawa City Passenger Railway [see Thomas Coltrin Keefer*], which operated horse-drawn cars, and in 1894 they consolidated the two firms to create the Ottawa Electric Railway Company, the only street railway in Canada to receive a federal charter.

The previous year they had also invested in an old Ottawa carriage-building shop, which became the home of the Ottawa Car Company (renamed the Ottawa Car Manufacturing Company in 1913). Its production was geared to the needs of the Ottawa Electric Railway and other street-railway companies in Canada. It built streetcars, locomotives, and snow-removal equipment and was one of the most important manufacturers in the city. OCC streetcars were furnished with heaters produced by the Ahearn Electric Heating and Manufacturing Company. In 1894 Ahearn, together with John William McRae*, Erskine Henry Bronson, and others, incorporated the Ottawa Electric Company, creating a monopoly on commercial and residential illumination in the city. A year later he and Soper further extended their business and formed Ottawa Porcelain and Carbon to supply their electric companies with insulators, battery jars, arc-light carbons, motor brushes, and other small related articles.

Ahearn held Canadian patents for items ranging from an electric oven to an iron, a water-bottle warmer, and a streetcar heating system. His patents reflect his professional life and private interests. His early efforts focused on telegraphy and telephony; these were followed by his inventions in the field of electricity. His later patents related to his personal interest in music recording and reproduction. However, it was his ability to find solutions to particular technological obstacles impeding the progress of large systems that gave his companies an edge over the competition. He was always innovating, interconnecting his machinery in new ways, and adapting inventions to his needs. He was also a master of promotion. On 29 Aug. 1892 he invited members of the Ottawa elite to an “electric” banquet. An entire meal was cooked in a powerhouse on electrical appliances that he had designed and constructed. The food was delivered to the dining room of the Windsor hotel by streetcar.

Very few families in Ottawa in the 1890s could afford a carriage for trips outside the city. Ahearn transformed a property in Rockcliffe into a recreational park with rails winding through the woods overlooking the Ottawa River, an electric merry-go-round, impressive arc and incandescent illumination, and live music. He then extended the service of the Ottawa Electric Railway from New Edinburgh to Rockcliffe Park, increasing the ridership and his company’s revenue. In 1900, when the firm introduced a Sunday service, Ahearn invested in a Britannia Bay property and built a second amusement park, which became a favourite location for weekend family picnics. He was the first person in Ottawa to drive a car – powered, of course, by electric storage batteries. Similar cars were then exhibited and offered for sale at a local fair.

A staunch Liberal, Thomas Ahearn created powerful political alliances throughout his career that allowed him to build a business empire unusually free from municipal regulation. His friendships with prime ministers Sir Wilfrid Laurier* and William Lyon Mackenzie King* were close. King recalled in his journal, for example, that Ahearn had helped to finance the purchase of Laurier’s house, which was later left to King.

In 1927 Ahearn provided the technical expertise for the first official transatlantic telephone call made by a Canadian prime minister to Britain. The same year he was appointed the chairman of the broadcasting committee for the diamond jubilee of confederation and oversaw the earliest coast-to-coast radio broadcast. Also in 1927 Ahearn was named the first chairman of the Federal District Commission (forerunner of the National Capital Commission), a position he held for five years, and in 1928 he became a member of the Privy Council of Canada. At the end of his life Ahearn was involved in real estate and finance. He served as a director of the Bank of Montreal, the Guarantee Company of North America, Royal Trust, the Ottawa Investment Company, and the Ottawa Land Association.

Thomas Ahearn’s career was truly remarkable. Although he was born in a poor working-class family, he became one of Ottawa’s richest and most influential entrepreneurs. His outstanding technical expertise, but also his intuition, allowed him to compete successfully with members of the city’s business elites and build powerful political alliances. Through the companies he founded and the institutions he led, Ahearn realized his vision of Ottawa as a modern, industrialized capital and greatly contributed to its transformation in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Thomas Ahearn held Canadian patents nos.9936, 17669, 18042, 35896, 38976, 39506, 39507, 39508, 39915, 39916, 39917, 177935, 189071, 191939, and 208058 (Canadian Intellectual Property Office, “Canadian patents database”: brevets-patents.ic.gc.ca/opic-cipo/cpd/eng/introduction.html (consulted 7 Jan. 2014)).

AO, RG 22-354, no.1592; RG 80-5-0-123, no.2304; RG 80-5-0-193, no.2596; RG 80-8-0-123, no.2793; RG 80-8-0-552, no.9342. LAC, “Diaries of William Lyon Mackenzie King”: www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/discover/politics-government/prime-ministers/william-lyon-mackenzie-king/Pages/diaries-william-lyon-mackenzie-king.aspx (consulted 7 Jan. 2014); R3084-0-5; R10811-0-X. Fred Cook, “Hon. Thos. Ahearn as I knew him,” Evening Citizen (Ottawa), 28 June 1938: 14–15. Ottawa Citizen, 30 Aug. 1892, 28 June 1938. Anna Adamek, “Incorporating power and assimilating nature: electric power generation and distribution in Ottawa, 1882–1905” (ma thesis, Univ. of Ottawa, 2003). Fred Angus, “Seven hundred days: the story of Ahearn & Soper and the beginning of electric traction in Ottawa,” Canadian Rail (Saint-Constant, Que.), no.377 (November–December 1983): 188–216. F. L. G. Askwith, “An historical sketch of the electrical utility industry in the Ottawa area” (unpublished paper, 1973; copy at the City of Ottawa Arch., Ottawa Hydro fonds (MG 039)). Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898 and 1912). Greg Gyton, A place for Canadians: the story of the National Capital Commission (Ottawa, 1999). D. C. Knowles, The Ottawa Car Company, 1892–1948 (Ottawa, 2003).

Cite This Article

Anna Adamek, “AHEARN, THOMAS,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 5, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/ahearn_thomas_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/ahearn_thomas_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Anna Adamek |

| Title of Article: | AHEARN, THOMAS |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2017 |

| Year of revision: | 2017 |

| Access Date: | March 5, 2026 |