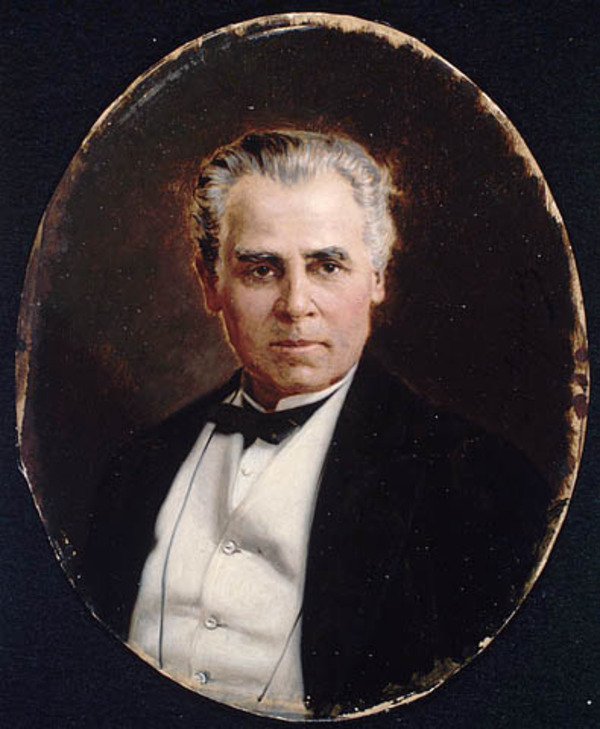

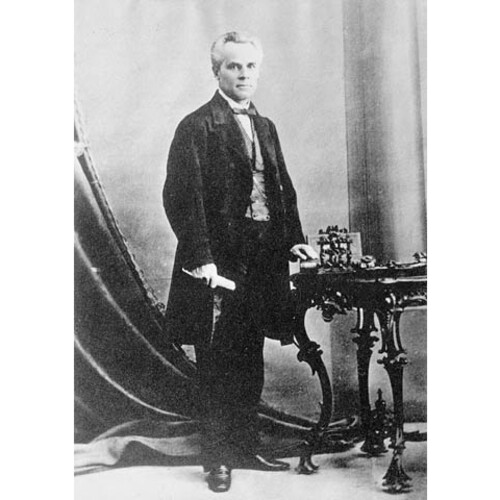

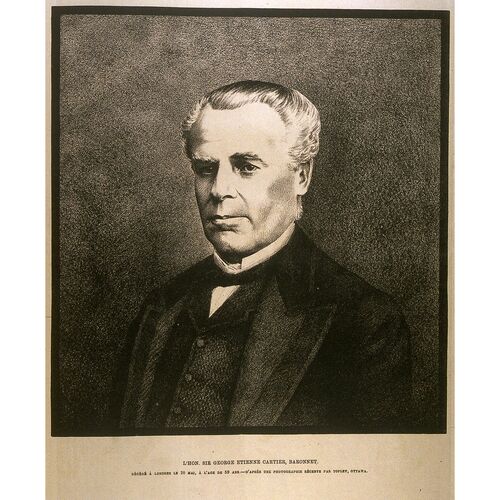

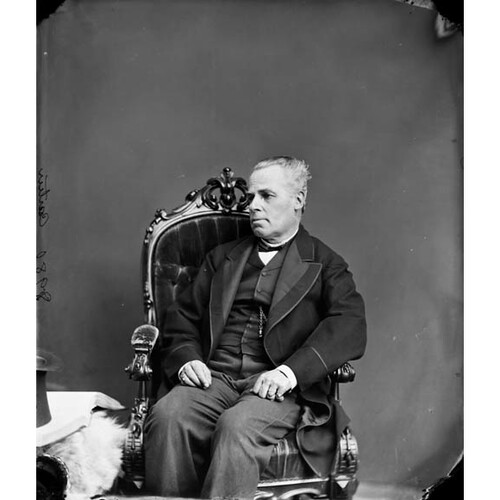

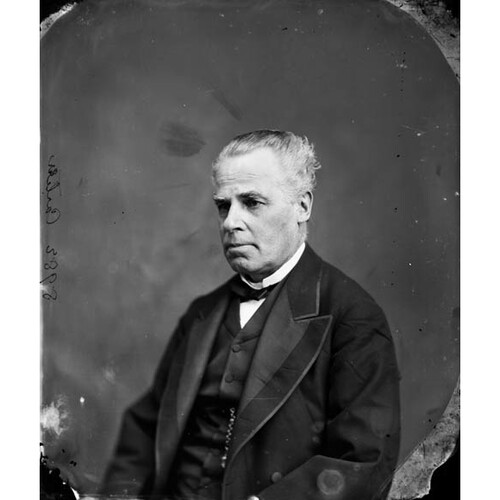

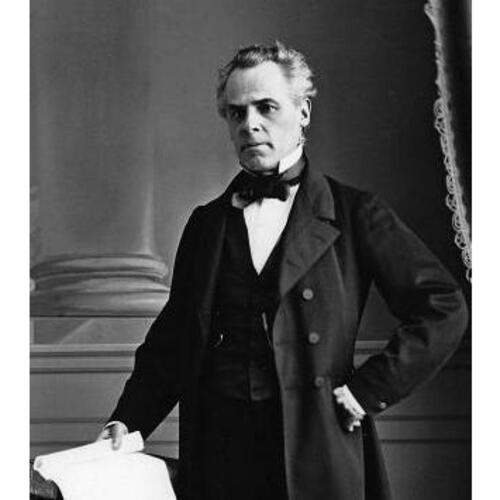

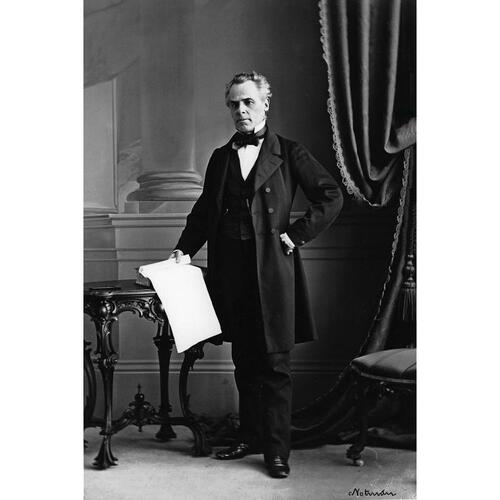

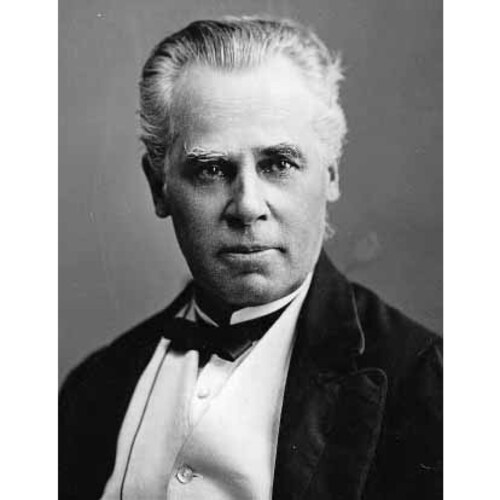

CARTIER, Sir GEORGE-ÉTIENNE, lawyer, politician, prime minister of the Province of Canada; b. 6 Sept. 1814 at Saint-Antoine-sur-Richelieu (Verchères County, L.C.), son of Jacques Cartier (1774–1841) and Marguerite Paradis; d. 20 May 1873 in London, Eng.

Cartier’s family made no claim to have descended from the discoverer of Canada, who had no children, but they were content to believe, without seeking proof, that a distant ancestor had been a younger brother of the Saint-Malo navigator; they were wrong, although he may have belonged to the same family. All the same, George-Étienne Cartier was coquettish enough to call the country house that he owned near the village of Hochelaga “Limoilou,” after Jacques Cartier*’s manor.

In 1738 Jacques Cartier, dit l’Angevin, of Prulier in the diocese of Angers, France, set out for New France. In 1744 he married Marguerite Mongeon at Beauport, and became a salt and fish merchant at Quebec. In 1772 one of his sons, Jacques*, settled at Saint-Antoine-sur-Richelieu, about 36 miles from Montreal. There he engaged in the grain trade and from 1804 to 1809 represented the constituency of Surrey, later Verchères, in the House of Assembly of Lower Canada. He left his son Jacques a sizeable fortune, which allowed him to lead the agreeable and easy life of a wealthy country squire. Eight children were born of the marriage of Jacques Cartier and Marguerite Paradis in 1798; George-Étienne was the seventh. Another son, François-Damien, also practised law, and was the professional partner of the politician.

Cartier, baptized on the day of his birth at Saint-Antoine-sur-Richelieu, received the name of George in honour of the reigning sovereign George III, hence the English spelling. As there was no school at Saint-Antoine, the boy was first educated by his mother. In 1824 he entered the college of Montreal, directed by the Sulpicians, with whom he retained connections all his life. He was a diligent and brilliant pupil. He completed his secondary education in 1831, and then started his legal training in the office of Édouard-Étienne Rodier*, a Montreal lawyer, who was favourably disposed towards the demands of the Patriote party. Called to the bar of Lower Canada on 9 Nov. 1835, he began to practise his profession with his former employer, also continuing to take an active interest in the struggles that marked these years of great excitement, especially in the region of Montreal.

While he was a student Cartier had worked during the 1834 elections on behalf of Louis-Joseph Papineau and Robert Nelson. On 24 June of the same year, at a banquet in Montreal which heralded the birth of the Société Saint-Jean-Baptiste, he had sung a song that he had just composed and that was to survive him, O Canada, mon pays, mes amours. At the 1835 banquet he sang another patriotic song he had composed, Avant tout je suis Canadien, which later became a rallying-call for the Fils de la Liberté, an association of French Canadian militants, to which Cartier belonged [see Leblanc]. Furthermore, in May 1834 he had been one of two secretaries of a political organization set up under the name of the Comité Central et Permanent du District de Montréal, which demanded that the government respect civil liberties. During the autumn of 1837, when the situation worsened in Lower Canada and rumbles of revolution were heard in assemblies [see Papineau], Cartier took part in the events in circumstances which, although unclear, enable us to situate him among those called Patriotes. Later on, his participation in the 1837 disturbances did not seem to him a gesture against England, even if he took pleasure in recalling with a smile that he had been a “rebel”; he claimed that it was, rather, a youthful escapade in which, as he wrote on 20 Sept. 1838 to Charles Buller*, the secretary of Lord Durham [Lambton*], he had not “forfeited his allegiance to the government of Her Majesty in the province of Lower Canada.” It was, he said, against an oppressive minority rather than against the crown that he had fought, as is shown by these words uttered on 24 Sept. 1844 in a speech at Saint-Denis: “There is no longer any danger of a return to the events of 1837, caused by the actions of a minority which desired to dominate the majority and exploit the government in its own interests. The events of 1837 have been badly interpreted. The object of the people was rather to reduce this oppressive minority to nothingness than to bring about a separation of the province from the mother-country.” However that may be, Cartier, who was probably not present at the assembly of the six counties, held at Saint-Charles on 3 October, was at the battle of Saint-Denis on 22 November, and far from deserving the accusations of pusillanimity heaped upon him by some of his opponents, he seems to have acquitted himself bravely. In his speech at Saint-Denis in 1844 he was able to exclaim without being contradicted: “I was of your number, and I do not think I showed lack of courage.”

After the Patriotes’ defeat at Saint-Charles, Cartier, who had remained at Saint-Denis, had to hide, with his cousin Henry Cartier, at Verchères, where he spent the winter with a farmer. His death was announced in the papers, but in reality he had to flee to the United States after his hiding place was discovered. He lived at Plattsburgh and Burlington (Vermont) from May to October 1838. A proclamation of 9 Oct. 1838 annulled Durham’s ordinance, by which on the preceding 28 June Cartier had been included among those accused of treason. He then returned to Montreal and took the authorities to witness that his conduct was “the most pacific and the most irreproachable.”

The following year Cartier returned to the practice of law with his brother François-Damien. His great period of activity as a lawyer extended from this year until 1848. After he became a minister, in 1854, he no longer had the time or the opportunity to concern himself personally with his clientele. He had as partners later François-Pierre Pominville, Louis Bétournay, and Joseph-Amable Berthelot, and his office numbered among other clients the Grand Trunk and the Sulpicians. In 1852 Cartier introduced in parliament the bill creating the Grand Trunk Railway Company. On 11 July 1853 he was appointed its legal adviser for Canada East. His opponents were quick to accuse him of collusion with the biggest railway company of the day. In 1854, to an mla who accused him of being an agent of the Grand Trunk and receiving money from it, Cartier replied: “But I do not depend upon the company. I am independent, my private clientèle renders me so . . . the public has had sufficient confidence in me as a lawyer to render me independent of all emolument I may receive from the Grand Trunk company.” One must nevertheless note that according to the deed of partnership between Cartier and Pominville, the politician was entitled to only one fifth of the income received, and that this restriction did not apply to the business of the Grand Trunk Company.

While carrying on his profession, Cartier continued to take an interest in public affairs. At the time of the reorganization of the Société Saint-Jean Baptiste in 1843, he became its secretary. In the political sphere, he accepted the union, became a supporter of Louis-Hippolyte La Fontaine*, and demanded the application of the principle of responsible government. On 18 Sept. 1842, immediately following the formation of the first ministry of La Fontaine and Robert Baldwin*, Cartier wrote to La Fontaine to congratulate him and tell him of his enthusiasm: “Your appointment has electrified our hearts and our spirits.” Cartier seems to have quickly accepted the idea that armed resistance to authority was useless, and that it was better to seek to bring about constitutional reforms. In 1844, when the La Fontaine–Baldwin ministry resigned as a result of the refusal of the governor, Sir Charles Theophilus Metcalfe*, to accept its recommendations, Cartier campaigned in favour of ministerial responsibility in the general elections that followed. Because he did not feel sufficiently established in his profession, he rejected a number of proposals that he should himself be a candidate, but finally agreed to stand against Amable Marion in a by-election in Verchères; on 7 April 1848 he was elected a member of the Legislative Assembly of United Canada. It was then that his true political career began; it continued uninterrupted until his death.

Cartier took his seat at the session that began at Montreal on 18 Jan. 1849, and that was marked at the end of April by the adoption of the rebellion losses bill and by the ensuing riot. He was in favour of the measure, although he did not take part in the debate. He also sided with La Fontaine in the debate that pitted the latter against Papineau. To the former leader who had returned to politics after his years of exile and who asked for the repeal of the union, La Fontaine replied that the regime had been planned in order to crush the French Canadians, but that the latter had succeeded in utilizing it for their own benefit, and they must continue to extract every advantage from it. Cartier was to put this idea into practice. Only one of his speeches during this session has been preserved, one dealing with the St Lawrence and Atlantic Railway and delivered on 15 Feb. 1849; in it all the interest he was to take in railway development, to which he was accused of being slavishly devoted, is already apparent. That same year, as an mla, he protested against the movement started among politicians and businessmen, particularly of English origin, in favour of the annexation of Canada to the United States, and the subsequent published Annexation Manifesto [see Holton]. Cartier all his life had an almost morbid fear of the United States, and was always strongly opposed to its republican institutions. He continued to dread annexation, and in 1870, in a speech against a possible customs union with the United States, he went so far as to say: “Individually, the Americans are good neighbours, but as a nation, there are no individuals in the world who are less liberal towards other peoples, except the Chinese.”

Cartier soon showed himself to be one of the most important French Canadian mlas. He was re-elected by acclamation in Verchères in the general election of December 1851, and in 1852 took his seat at Quebec, now once more the capital. La Fontaine had just retired, and power was held by the moderate Reformers, led by Augustin-Norbert Morin* and Francis Hincks*. In general, Cartier supported the two men, but he refused to join the government they directed; he frankly admitted, in a speech on 22 Sept. 1852, that the inadequate stipend attached to the post offered was one of the reasons that prevented him from accepting. Cartier defended the government’s policy, nevertheless, against the opposition, which reproached it for postponing the discussion of important questions, such as the secularization of the clergy reserves and the abolition of seigneurial tenure. The government was however in a minority, and it decided to appeal to the governor general, Lord Elgin [Bruce*], to dissolve parliament and call a general election. In August 1854, Cartier was re-elected in Verchères over L.-H. Massue. Of the three groups of representatives returned – the moderate Reformers of Lower and Upper Canada who supported the Hincks–Morin government, the radical Reformers of Upper and Lower Canada, and the Conservatives – none possessed an absolute majority, and none could form a stable government. From the first day of the session, when the speaker was elected, the Hincks–Morin ministry saw how precarious its position was. The Reformers had decided at a general meeting that Cartier should be their candidate for this post. For their part, the Clear Grits and the Conservatives of Upper Canada were in favour of John Sandfield Macdonald, who had already held the post, and the Lower Canadian opposition wanted Louis-Victor Sicotte*, the mla for Saint-Hyacinthe. Cartier was proposed on 5 Sept. 1854, but only collected 59 votes against 62, and it was Sicotte who was finally elected. Despite its weakness, the government continued to sit until 7 September, when it was defeated on a question of privilege. The Hincks–Morin government resigned, and an alliance of the Conservatives and moderate Reformers then took place; it was the origin of the Liberal-Conservative party. This coalition supported the ministry of Allan Napier MacNab* and Augustin-Norbert Morin, who was replaced on 27 Jan. 1855 by Étienne-Paschal Taché*. When the MacNab-Taché government was set up, Cartier was called upon to assume the office of provincial secretary for Canada East. As the law required that a minister should have his mandate renewed by his electors, Cartier stood again in Verchères. His opponent was Christophe Préfontaine, and he emerged victorious from a violent struggle waged against him by the radical Reformers, the Rouges, with whom he would have to contend from then on. On 24 May 1856 the MacNab-Taché ministry was replaced by that of Taché and John A. Macdonald*, and Cartier became attorney general for Canada East. On 26 Nov. 1857, as Prime Minister Taché had decided to give up active politics, John A. Macdonald, with Cartier, formed a government; in this government, which was called Macdonald–Cartier until 1 Aug. 1858 and then, from 23 May 1862, Cartier–Macdonald, Cartier remained attorney general.

Since La Fontaine had departed and Taché was growing old, Cartier had become the most influential man in the Lower Canadian section. At the elections held at the end of 1857, following the formation of the ministry, Cartier was re-elected in Verchères over his former opponent Préfontaine but was defeated in Montreal, where he had also stood, by Antoine-Aimé Dorion*. (In the general election of 1861, Cartier stood only in the newly created riding of Montreal East, and this time he emerged victorious from the battle against A.-A. Dorion.) For some years the assembly had been discussing the selection of a permanent capital: the cities of Quebec, Montreal, and Bytown (Ottawa) had been suggested. In 1857, nonplussed by varying opinions, the Macdonald–Cartier ministry obtained approval for an address to the queen in which she was requested to choose a capital. On the advice of her Canadian ministers, she decided on Ottawa. At first a supporter of Montreal, Cartier had finally come round to Ottawa, a choice which at the time seemed surprising, but which was consistent with the development of Canada westwards. In July 1858, when the royal decision was made known, a motion passed by a vote of 64 for and 50 against stating that “in the opinion of this House the City of Ottawa should not be the permanent seat of the government of this province.” The Macdonald–Cartier ministry decided to resign and was replaced for two days by a ministry led by George Brown and Antoine-Aimé Dorion; it was unable to preserve the majority required to remain in power because of the necessity for the new ministers to be re-elected. To avoid this difficulty the Cartier–Macdonald ministry, which replaced it, resorted to a device that has remained in history under the name of “double shuffle.” Interpreting strictly the law that dispensed with re-election for a minister called to another ministerial post within a period of one month after his resignation, the ministers first accepted portfolios different from those they had held in the former government, and the next day resumed their former offices, thus being freed from the obligation to be re-elected. The Cartier–Macdonald ministry did, however, have to resign in May 1862, after being defeated in the house on the second reading of the Militia Bill: several supporters of Cartier deserted him on the grounds that the new law would result in excessive expenditure.

During this period from 1857 to 1862, Cartier gave evidence of great activity. In the autumn of 1858 he went to London with Alexander Tilloch Galt* and John Ross to put before the English government a plan for the federation of the provinces of British North America. Cartier had expressed approval of such a measure in August 1858, when Galt had entered the government on condition that it accept his plan of federation. However, in the face of the reticence of the other provinces, the English government did not deem it wise to put the plan into effect. Cartier was received by Queen Victoria, and it was on this occasion that he stated that an inhabitant of Lower Canada was an Englishman who spoke French. In the summer of 1860, in his capacity as prime minister, he accompanied the Prince of Wales during his visit to Canada and with him, on 25 August, officiated at the opening of Victoria Bridge, of which he had encouraged the construction [see Hodges].

As a minister and prime minister, Cartier was the guiding spirit behind many legislative measures; these measures contributed, in the middle of the last century, to the development of United Canada, and established institutions out of which have grown those that still govern Canada, and more particularly Quebec. In 1855 the government of which Cartier was a member had passed the Lower Canada Municipal and Road Act of 1855 (18 Vict., c.100), which created municipalities corresponding to the church parishes and grouped them in county municipalities; it was the basis of the system still to a great extent in force in Quebec. In 1860 Cartier had this law reshaped, and on 6 March declared that “our municipal system is one of the principal institutions in Lower Canada.” He was also a supporter of the organization of primary education in Lower Canada. In 1856 he completed the fundamental 1846 Act (9 Vict., c.27), which established schools in all parishes and confirmed the principle of the religious duality of these schools, by having parliament decree that a council of public instruction be formed, made up of Catholics and Protestants (19 Vict., c.14), and that there be established some training schools for male and female teachers (19 Vict., c.54). He was not a member of the government when, on 18 Dec. 1854, an act for the abolition of feudal rights and duties in Lower Canada (18 Vict., c.3) was ratified, but he had long been in favour of this measure, and in 1853 he had declared categorically: “The seigniorial tenure retards the progress of the country.” In 1859, he was to have a law passed which Upper Canada scarcely liked, and on which discussion was lengthy – one sitting lasted 39 hours – to increase the compensation to be paid to former seigneurs, a law that in Cartier’s words “will satisfy all the large interests and . . . do justice to the seigniors as well as to the censitaires” (22 Vict., c.48). In 1856 he took part in a reform of the Legislative Council, accepting with some reservations, its elective basis.

It was in the sphere of the administration of justice, and in that of law, that Cartier was to accomplish his greatest reforms. In 1857 he got parliament to enact that in the Eastern Townships, populated mainly by Anglophones, French laws would apply as elsewhere in Lower Canada (20 Vict., c.43). The uncertainty that had hitherto prevailed threatened to create a system of personal law under which persons of the same territory were judged according to different law, by reason of their origins. In the same year, going against old traditions, he brought about the decentralization of the judiciary (20 Vict., c.44). By this measure, the number of judges in Lower Canada was considerably augmented, and new judicial districts were instituted outside the large towns. The work of which he was most proud was the codification of civil law. In 1857 he had an act passed “to provide for the codification of the laws of Lower Canada relative to civil matters and procedure” (20 Vict., c.43). To this end provision was made for the setting up of a commission; its president was Judge René-Édouard Caron, who did excellent work during the period 1859 to 1865. Cartier had parliament approve the plan that was drafted (29 Vict., c.41), and the civil code of Lower Canada came into operation on 1 Aug. 1866. The commission then codified the rules of civil procedure, and they were given effect on 28 June 1867. Cartier also, with John A. Macdonald, initiated the great legislative compilations which in 1859 made it possible to publish, in English and French, The consolidated statutes of Canada, and, in English, The consolidated statutes for Upper Canada; in addition, in 1861 The consolidated statutes for Lower Canada appeared in French and English. Hence La Minerve was able to write on 21 May 1873, at Cartier’s death: “Besides what he has done for the advancement and material prosperity of our country, M. Cartier can claim the honour of having remoulded the legislation of Lower Canada, and of having endowed us with a code of laws which, in this respect, raises us to the level of the most civilized nation in Europe.”

Standing out as he did against the ministry of John Sandfield Macdonald and Louis-Victor Sicotte from 24 May 1862 to 15 May 1863, and that of J. S. Macdonald and Antoine-Aimé Dorion from 16 May 1863 to 29 March 1864, Cartier was the government’s chief opponent. In the general election of July 1863, he again was a candidate in Montreal East, where he defeated Antoine-Aimé Dorion. The latter had for several years been Cartier’s principal opponent in Lower Canada. The liberal ideas that he defended were precisely those that Cartier despised. Dorion’s alliance with George Brown harmed him in the minds of the Catholic hierarchy, with which Cartier was on good terms, and despite his great qualities he was forced to spend almost all his life in the opposition.

The session that opened at Quebec on 19 Feb. 1864 was to return Cartier to power and bring about the birth of confederation. At the beginning of the session, Cartier violently criticized the government of J. S. Macdonald and Dorion, which enjoyed only a slight majority. On 25 February he began one of the most fiery and lengthy speeches of his career, which went on for 13 hours and throughout several sittings, and in which he attacked the entire policy of the government. Finally, on 21 March, without waiting to be overthrown, the government resigned. The governor general, Lord Monck*, then called on Cartier to take office, but the latter refused, alleging as a pretext that in the circumstances it was better to put at the head of the administration a man less involved in the political struggles of the last few years. The governor followed his advice, and asked Étienne-Paschal Taché, a legislative councillor and former prime minister, who had almost entirely retired from political life in 1856, to form a ministry. Taché accepted, with John A. Macdonald as his counterpart for Upper Canada, and Cartier entered the government as attorney general for Canada East.

On 14 June 1864 the Taché–Macdonald government was defeated as a result of a vote of censure in the house for neglecting to give effect to a loan previously promised to the City of Montreal. In six years, it was the sixth ministry overthrown; no group seemed capable of taking hold, and a general election, the third in three years, did not seem to be a solution. Then on 16 June after some days of manoeuvring, discreetly directed by Lord Monck, a coalition ministry was formed; its leader was theoretically Taché, but the real leaders on the Conservative side were John A. Macdonald and Cartier, with whom George Brown had agreed to ally himself on condition that the constitutional difficulties of the past few years be settled. Like Cartier, the political leader of Upper Canada set aside his personal antipathies for the sake of a national objective. All groups, except the radical liberals of Lower Canada, whom Cartier did not need and whom he regarded as his irreconciliable enemies, were represented in the coalition, which was given its essential character by the presence in the same ministry of Cartier and Brown. Up to then they had been unyielding adversaries, but they agreed to unite in order to bring about the federation of Upper and Lower Canada, or, if possible, the confederation of all the colonies of British North America. Indeed, the new government undertook to “bring in a measure during the next session for the purpose of removing existing difficulties by introducing the federative principle into Canada, coupled with such provisions as will permit the Maritime provinces and the North-West Territories to be incorporated into the same system of government.”

Within the coalition ministry, Cartier was one of the men chiefly responsible for the birth of confederation. After the setback of 1858, he was convinced that a plan emanating from a coalition government would be more acceptable to the mother country. The British government was moreover now in favour of such a plan, as a result of the inquiry that the secretary of state for the colonies, the Duke of Newcastle [Clinton], had circumspectly conducted when he had accompanied the Prince of Wales to Canada in 1860. Cartier became the advocate of a federation of the provinces of British North America because it appeared to him the best way of extrication from the political difficulties of the period, created especially by the question of representation by population. Lower Canada, which in 1840 had received representation equal to that of the less populous Upper Canada, now was favoured by the subsequent reversal in proportions. Cartier realized that Lower Canada could not hold out indefinitely against rep by pop, and that acceptance of it would not have as many disadvantages in a federative state: several areas important for French Canadians, such as education and justice, would be dependent on a local legislature. Cartier also feared annexation to the United States, and in 1865 he declared: “We must either have a Confederation of British North America or else be absorbed by the American Confederation.” In order to consolidate the federation of the provinces, and ensure their expansion and economic development, Cartier strongly encouraged the building of the Intercolonial, which was to make Canada one country from east to west. His connections with the railway companies, and the fact that his legal office represented the Grand Trunk – which would gain from the extension of the line towards the Atlantic ports – had no doubt prompted him to favour such a programme, necessary, he felt, for the development of the south shore of the lower St Lawrence. Finally, it was natural that as a politician he should desire to play a role on a larger stage. From June 1864 to 1 July 1867, Cartier bent his energies and intelligence to the realization of the federative project.

Cartier was a member of the United Canada delegation that took part in the Charlottetown conference at the beginning of September 1864, and he was one of the principal speakers who succeeded in convincing the representatives of the other colonies of the advantages of a confederation. By his speeches in favour of the plan, he also participated in the publicity that marked the delegates’ return journey via Halifax and Saint John, N.B. At the Quebec conference, held behind closed doors from 10 to 27 October and for which no official account exists, Cartier seems to have remained on the whole silent. This attitude is explained by the fact that the delegates from the colonies were studying John A. Macdonald’s proposals, which had been prepared beforehand by the cabinet of United Canada; Cartier had preferred to defend there the measures he believed necessary to safeguard the interests of his Lower Canadian compatriots. At the session of February and March 1865, the Quebec resolutions, containing the details of the plan for federalism, were discussed and approved. Cartier defended them in a long speech on 7 Feb. 1865, first quoting certain texts at length, to prove that the French Canadians had preserved their institutions, their language, and their religion by their adhesion to the British crown, and that furthermore, by not responding to invitations from Washington at the time of the revolution, they had made it possible for British power to continue in America. He concluded: “These historical facts teach us that French-Canadians and English-speaking Canadians should have for each other a mutual sympathy, having both reason to congratulate themselves that Canada is still a British colony.” “If we unite,” he added, “we will form a political nationality independent of the national origin and religion of individuals.” He was opposed to the “democratic system which prevails in the United States,” proclaiming that “in this country we must have a distinct form of government in which the monarchical spirit will be found.” He asserted that the clergy were in favour of confederation. “The clergy in general,” he said, “are opposed to all political dissension, and if they are favourable to the project, it is because they see in confederation a solution to the difficulties which have so long existed.” Subsequently he intervened several times during the debate in the house to answer the arguments of the project’s opponents. In particular he opposed an appeal to the people that Antoine-Aimé Dorion wanted to make in order to ascertain popular feeling towards this measure. On 13 March he even went so far as to admit formally, half seriously and half in jest: “It is true, I consult no one when I want to make a decision.” He alleged as a pretext the urgency that there was to submit the project to the British government once the assembly had approved it, in accordance with the agreement with the other colonies, even if the latter had not approved in their turn. Indeed, it became evident that the Newfoundland and Prince Edward Island legislatures would not adopt the plan that had been conceived at Quebec. Furthermore in the general election of March 1865 in New Brunswick the supporters of confederation were defeated, and in Nova Scotia the legislature showed some reserve. Despite this situation, Cartier went to London in April, after the session, to present to the government the plan for federalism conceived at the Quebec conference and approved by the legislature of United Canada.

Having returned to Canada at the beginning of July 1865, Cartier continued to play the part of the real leader of the French Canadian majority in the ministry directed by Sir Narcisse Fortunat Belleau*, after Taché’s death in July 1865. He took part in the last session held at Quebec, from 8 Aug. to 18 Sept. 1865, and in the first held at Ottawa, from 8 June to 15 Aug. 1866. During the latter session Cartier won acceptance of the plan for the future constitution of Quebec, which provided for the existence of an upper, non-elective chamber; such a chamber was not proposed for Ontario. According to Cartier, economic considerations were not a reason for refusing to give more dignity to our legislative institutions. In reality, a Legislative Council had been established in Quebec for another more precise motive, which his contemporaries stressed: it was intended to protect the Anglo-Saxon minority from the possibility of being harmed by any measure emanating from a lower chamber that represented the popular feeling of the French Canadian majority. It was also during this session that the government of which Cartier was a member suffered a reverse, while attempting to settle the problem of minority rights in education. On 31 July, Hector-Louis Langevin*, solicitor general for Canada East, introduced a bill, inspired by Galt, the object of which was to ensure more rights for Protestants in Quebec. The natural reaction of the Catholics in Upper Canada was to ask that they be granted similar rights, and on 1 August the mla for Russell, Robert Bell, whose riding on the borders of French Canada was inhabited by many Catholics, introduced on behalf of the separate schools of Upper Canada a bill corresponding to Langevin’s. As the mlas for Upper Canada were opposed to the measure, the government withdrew Langevin’s bill, and Bell did the same with his. Galt resigned from the ministry, and Cartier felt obliged to declare, in a speech given at Montreal on 30 Oct. 1866: “After telling you that the Protestants of Lower Canada will have all possible guarantees, I must add that the Catholic minority in Upper Canada will have the same guarantees.” While the opposition newspapers highly approved of such a declaration, they expressed scepticism about this promise of Cartier’s, and asked what would be the concrete solutions. Cartier and his supporters never gave any precise details.

The fate of the Protestant and Catholic minorities under a future federation was to be discussed again and decided at the London conference. Cartier left Montreal for London on 12 Nov. 1866, and from 4 December on he took part in the work of the conference. The delegates from Canada, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia approved, with a few changes, the Quebec resolutions; these became the London resolutions, and finally the British North America Act, which was ratified by Queen Victoria on 29 March 1867. According to testimony published on 26 May 1873 in Le Constitutionnel of Trois-Rivières by Elzéar Gérin*, who was in London, John A. Macdonald tried to transform the federative system that had been accepted at Quebec into a much more centralized union. George-Étienne Cartier allegedly opposed it, and threatened his colleague that he would wire Prime Minister Belleau and ask for the ministry to be dissolved. Macdonald did not insist. This version has been accepted by some historians, without serious proof, but it remains true that Cartier continued in London, as he had at Quebec, to protect the interests of Lower Canada. He won for his French Canadian compatriots living in Quebec rights that he believed essential at the time. He wanted a Quebec that was master of its destiny in the matter of education, common law, and local institutions. Furthermore, he endeavoured to protect the religious rather than linguistic rights of the minorities in other provinces. One may even wonder whether Cartier believed in a veritable Canadian duality which would allow French speaking Canadians to enjoy their rights fully throughout the country from the point of view both of education and of the use of their language. On 15 January Cartier left London for Rome, where he was given an audience by Pope Pius IX. By the end of the month he was back in the British capital, where he took an enthusiastic part in social activities. He returned to Canada in the middle of May.

On 1 July 1867, the day of the official birth of the dominion of Canada, Cartier was at Ottawa. He entered the cabinet, formed by John A. Macdonald at the request of the governor general, Lord Monck, as minister of militia and defence. When the governor announced that Macdonald had been created by Queen Victoria a knight of the Order of the Bath, and that a number of other politicians, including Cartier, were made companions of the same order, a dignity inferior to the first, the French Canadian leader refused the distinction. In the spring of 1868 Cartier was created a baronet, which conferred on him the title of “Sir” and gave him a rank equal to that of the prime minister. At the end of August and beginning of September 1867, elections were held to choose representatives to the House of Commons and to the Legislative Assembly of Quebec. Cartier stood in Montreal East as candidate for both houses, as the law allowed. He was elected to Ottawa after a hot fight against the labour and liberal candidate Médéric Lanctot, and he was elected to Quebec against Ludger Labelle. His party gained a resounding victory in the federal and provincial elections. Out of 65 members from Quebec elected to the House of Commons, there were only 12 opponents of confederation. At Quebec, Cartier officially played a somewhat unobtrusive role, content to be merely a member of the house supporting the government of Pierre-Joseph-Olivier Chauveau*, which in fact was strongly under the influence of the federal body. In the general election of 1871, Cartier again managed to get elected to the Legislative Assembly of Quebec, over Célestin Bergevin, but, fearing the voting in Montreal, he stood in Beauharnois.

In August 1872, in the federal general election, Cartier was again a candidate in Montreal East. His Liberal opponent was Louis-Amable Jetté*, and he was defeated by a crushing majority, thus meeting what was called his “political Waterloo.” Instead of seeking election in another Quebec riding, which would have required the resignation of a Conservative member and probably resulted in a contested election, Cartier agreed to stand in Provencher, Manitoba, where Louis Riel* and Henry James Clarke were contestants. The latter gave up his candidacy at the request of the lieutenant governor, Adams George Archibald*. As for Riel, he withdrew after much hesitation, acceding to the earnest requests of Alexandre-Antonin Taché*, archbishop of Saint-Boniface, who was happy to avert in this way the complications that the presence of the Métis leader would certainly have brought about at Ottawa. Cartier therefore had no opponent and was elected in September 1872 without even going to the riding, which he was never to see.

Cartier’s defeat in the riding of Montreal East which he had represented for 11 years, and in a town for which he had worked diligently, occasioned surprise and even regrets among his opponents. The governor general, Lord Dufferin [Blackwood*], even wrote to Cartier to express his complete sympathy, and Ignace Bourget*, bishop of Montreal, offered him his condolences. Worn down by illness, Cartier had aged, and had lost his erstwhile ascendency over his supporters; the temporary rise of the Parti National, and to a certain extent the setback that the New Brunswick school question might have seemed to be for Cartier, explain his defeat. At the end of 1871 a certain number of young Liberals, particularly from the Montreal region, among them Louis-Amable Jetté, had attempted to make a synthesis of the best ideas of the two great parties, and had started the Parti National in order to transform the political atmosphere. They were rapidly to return to the Liberal party, but they had time, with their aggressive spirit, to contribute to Cartier’s defeat. Furthermore, during the 1871 session the New Brunswick legislature had passed a law declaring that in order to obtain state aid schools must be neutral, which to all intents and purposes made it impossible for the Catholic schools to operate. The latter existed in New Brunswick by virtue of custom, not of law, and thus they could not avail themselves of the protection afforded by article 93 of the British North America Act. In the 1872 session the federal parliament was asked to intervene, and Cartier, in a speech delivered on 29 April, while deploring that New Brunswick had passed the law which had come under attack, admitted that it was valid, and that the protection of minorities at the beginning of federalism was proving to be weak. He was seriously reproached in Quebec.

From 1867 until his death, Cartier was Macdonald’s principal lieutenant, and often replaced him as prime minister and leader of the government in the House of Commons. He was a kind of co-prime minister, practically the equal of Macdonald. Officially, he was minister of militia, and attached much importance to this task. He proposed, as a Quebec newspaper put it at the time, to take his “revenge for 1862.” He brought before the House of Commons what he regarded as one of the most important measures in his political career, a militia bill that set up a theoretical force of 700,000 men, authorized the formation of numerous regiments, and was the basis of the Canadian system of defence until the war of 1914 (31 Vict., c.40). In the speech that he delivered on 31 March 1868 to introduce the bill in the House of Commons, Cartier explained that he was establishing an active and a reserve militia comprising all the male residents of Canada, from the ages of 18 to 60. “The measure which he was about to introduce . . . would have afforded,” he was reported to say, “the means of protection and defence required during the last three years, but at a greatly reduced expenditure. Should there be another Fenian invasion they should be met with still stronger force than on the previous occasion. They would make known by their fortifications and militia measure that they were determined to be British. . . .”

Among Cartier’s achievements immediately following confederation, may be placed the negotiations that he conducted and the measures he had passed to extend Canada from the Atlantic to the Pacific. It was mainly Cartier who was the moving spirit behind the advance westwards; this was something in which he took great pride, but in which, in retrospect, he also saw a few flaws. In October 1868 Cartier and one of his government colleagues, William McDougall*, went to London to negotiate the acquisition of Rupert’s Land and the North-West Territory. As McDougall fell ill, the whole burden of the discussions with the British government and the Hudson’s Bay Company fell on Cartier alone. He remained in London until April 1869, and had the opportunity to mingle in the political and social life of the capital. Finally, at the beginning of spring, the British government made the company a proposal by which it would receive £300,000 for its territory and retain one-twentieth of the fertile belt. The shareholders accepted the offer, and Cartier returned to Canada in triumph, his negotiations having added more than a quarter of North America to the territory of Canada. At the end of May Cartier had approved by parliament the agreement concluded with the imperial government and the Hudson’s Bay Company (32–33 Vict., c.3); when the imperial parliament had in its turn ratified the agreement, the territories were officially joined to Canada on 23 June 1870. It was then necessary to organize these vast spaces, and create political and administrative cadres for the some 10,000 Métis, the descendants of Indians and French and Scotch white people, who lived in the Red River region. The Canadian government had made a clumsy attempt to occupy the new territory and already in the autumn of 1869 had found itself up against resistance from the Métis and from a provisional government directed by Louis Riel. It was Cartier who succeeded in negotiating a solution with Bishop Taché that satisfied most of the Métis’ requests, and that took concrete shape in May 1870 with the creation of a new province, Manitoba, which was given a political and administrative system analogous to that of Quebec (33 Vict., c.3). The Métis were guaranteed land; the rights of the two languages were recognized, and the schools of the religious minorities, whether they existed by virtue of law or of custom, were authorized.

It is also to Cartier that we owe in large part the entry of British Columbia into the Canadian confederation. During the spring of 1871, in the absence of John A. Macdonald, who was sick, he obtained the Canadian parliament’s approval for the address seeking the establishment of a sixth Canadian province, in return for the promise that it would be linked with the rest of Canada by a railway through the Rockies. “Before very long,” Cartier exclaimed prophetically, “the English traveller who lands at Halifax will be able within five or six days to cover half a continent inhabited by British subjects.” This became possible in 1885. The government, not wishing itself to build the railway, decided to entrust the responsibility for it to a company, to which in return it would ensure subsidies and grant blocks of land. In the spring of 1872, Cartier introduced a bill in the House of Commons that provided for the building of the Canadian Pacific Railway (35 Vict., c.71). It was at the time of the adoption of this bill that Cartier gave the exultant cry: “All aboard for the West!”

To carry out such a gigantic undertaking, the government had to choose between two financial groups that were competing for its favours. The Canadian Pacific Railway Company, headed by Sir Hugh Allan*, president of a large shipping concern, obtained the contract at the beginning of 1873. It was known that Allan was a political friend of Macdonald and Cartier, but it was none the less a surprise when, at the beginning of April 1873, the Liberal member Lucius Seth Huntington* rose in the House of Commons not only to expose the American origin of the capital of Allan’s company, but in particular to assert that the financier had in some sort purchased his contract by paying $350,000 into the Conservative party’s funds during the 1872 elections. In the inquiry that ensued, it was proved that Cartier had written to Allan, promising to allow him to build and run the railway, and that he had asked Allan in other letters for sums of money, which were in fact paid: Cartier himself had received $85,000. Such practices were part of the political customs of the day, but this time they were somewhat less than prudent. They are explicable in Cartier’s case only by the habit of power, the belief that the good of the party was identified with that of the country, and perhaps also by the beginning of an illness to which he was to succumb at the moment when what has been called the “Pacific Scandal” burst.

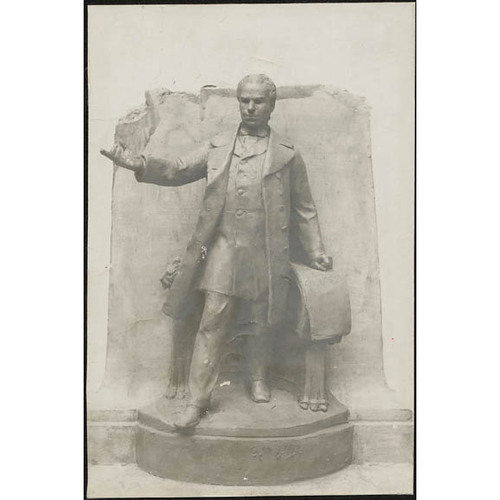

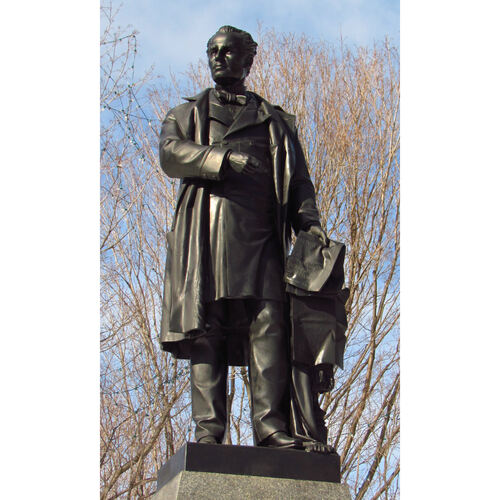

At the end of September 1872, after his defeat in Montreal East, Cartier had sailed for England to get treatment in London: he had been suffering since 1871 from chronic nephritis, known as Bright’s disease. He had spent the winter in England with his wife and his two daughters. On 20 May 1873 the transatlantic telegraph – Cartier had hailed its inauguration in July 1866 joyously – transmitted from London a telegram in which Sir John Rose*, the former Canadian minister of finance, then acting as a kind of semi-official representative of Ottawa to the imperial government, announced that Sir George had died that morning at 6 o’clock, and that his body would leave on the 29th for Quebec. The news reached Ottawa in the beginning of the afternoon, and John A. Macdonald, after announcing it to the House of Commons, burst into tears; incapable of continuing to speak, he remained with his right arm extended in a dramatic gesture over the empty seat of one who had been his companion for nearly 20 years. The Prussian, which was transporting Cartier’s remains, arrived at Quebec on 8 June. A Libera was chanted in the basilica at Quebec, and the coffin was then taken to Montreal. He lay in state in the Palais de Justice, then was conveyed, in the midst of a crowd such as Montreal had never known, to the church of Notre-Dame, where the funeral took place. Cartier was buried in the cemetery at Côte-des-Neiges, where a monument still recalls his memory.

Benjamin Sulte*, a journalist and historian, who during Cartier’s last years was one of his associates, has left a portrait of him that his contemporaries considered accurate: “Sir George,” he wrote, “was of medium height, even a little short, but one’s first impression was of a man of unusual vigour. Without being fat, he was somewhat plump and chubby, so much so that his nerves and muscles were so to speak hidden under this covering. His hands and feet were small, superbly moulded. His head, set straight on his neck, was extremely mobile. . . . The very French liveliness that one noticed immediately one approached him had nothing of that importunate character that the English say is peculiar to the French temperament.” The French writer Prosper Mérimée, who had met the Canadian statesman in Paris in 1858, wrote to one of his English correspondents: “I have seen M. Cartier. I was delighted to make his acquaintance. It seems as if I saw a Frenchman of the 17th century returned to visit the country which he had left two centuries before.” Cartier was not a great speaker. He spoke with precision and logic in French and in English, sometimes making a few mistakes in the latter. He was a great worker, a strong-willed man, sure of himself, almost overweening. He was a leader who imposed his will somewhat brutally. He could also be genial, particularly at the numerous gatherings held in his home at Ottawa during the last years of his life.

Cartier had a profoundly conservative mind. True, he accepted discoveries and progress; he understood better than some others the transformations that the acceleration of communications would bring about, and it was not out of mere personal interest that he was in favour of railways. But, in the realm of ideas, he feared innovations, and particularly those advocated by liberals inspired by the 1848 revolution and by American republicanism. He was attached to British institutions, which, in conferring responsible government, seemed to him to guarantee sufficiently the triumph of a democracy tempered by a non-elective upper chamber. From the religious point of view, he was not a mystic but a sincere Catholic. Among his possessions, after his death, was found an Imitation de Jésus-Christ in Latin, which he seems to have consulted frequently and in which he had underlined the conclusion of chapter XXIX, book 3 ; in English it reads as follows: “He who does not desire to please men nor fear to displease them will enjoy great peace.” For Cartier, to be a French Canadian was to be a Catholic. He was respectful of the clergy, to whom, according to him, French Canadians owed great gratitude, but he none the less preserved his full freedom of judgement and decision in temporal matters, so much so that he was regarded as a gallican. Immediately after confederation, he supported his former masters, the Sulpicians, in their opposition to the archbishop of Montreal, Ignace Bourget, who wanted to divide the parish of Montreal. He showed his gallican convictions on that occasion by claiming that it was the job of the state and not of the bishop to intervene in the civil organization of parishes.

By his marriage, which was solemnized on 16 June 1846 in the church of Notre-Dame at Montreal, Cartier had become allied to an excellent bourgeois family of Montreal. He had married Hortense Fabre, who was born on 28 Feb. 1828. She was the daughter of a wealthy merchant, Édouard-Raymond Fabre*, and the sister of Édouard-Charles Fabre*, the future bishop of Montreal, and of the journalist Hector Fabre*. Cartier and his wife had three daughters: Reine-Victoria, Joséphine, and Hortense. After Cartier’s death, Lady Cartier never returned to Canada, and died at Cannes in 1898. Cartier’s relations with his wife and her family were not always good. This situation was made public when some time after the statesman’s death his will was published; certain provisions of it revealed some mistrust with regard to Lady Cartier and her family. Its publication revived political quarrels, and La Minerve of 7 July 1873 contented itself with saying: “We ask only one thing of our friends, that is to study the testator’s intentions with impartiality and to take note of the expression of his religious sentiments which it contains.”

Cartier’s disappearance changed Canadian political life a great deal. For the Conservative party in Quebec it was one of the first blows that shook the omnipotence it had known at the beginning of confederation, and which it was not able subsequently to recover. In practice Cartier and Macdonald had been equal political leaders for more than a decade, and the former was never replaced in the search for a Canadian equilibrium. After La Fontaine and Morin, who in a brief period in power gave a new direction to politics, Cartier was the most illustrious of a long line of French Canadian politicians who were determined rightly or wrongly to play a role within institutions which, at first sight, seemed foreign to their spirit and their interests. When we judge him, we must place him in his time, and avoid condemning him in the light of the events that have taken place in the last 100 years, and that he could not reasonably have foreseen.

[The most complete biography of George-Étienne Cartier is by H. B. M. Best, “George-Étienne Cartier,” unpublished phd thesis, Université Laval, 1969. In his introduction, Best gives a list of the archival repositories he consulted, the main ones being the PAC, ANQ, and ASSM. The papers of the Cartier estate (property of the Succession Cartier, Montreal) also contain interesting information.

Best’s thesis has lessened the importance of other works as sources of information on Cartier. The main ones are: [G.-É. Cartier], Discours de sir Georges Cartier . . . , Joseph Tassé, édit. (Montréal, 1893); Cartier’s major speeches between 1844 and 1872 are found in this collection. There is no critical editing but it includes notes which place the speeches in the political context. The Parliamentary debates on confederation (Province of Canada) contain the speeches of politicians during the debate on the plan for confederation. They give a good picture of the various opinions held by the population as expressed by Cartier’s supporters and opponents. John Boyd, Sir George Etienne Cartier, Bart., his life and times: a political history of Canada from 1814 until 1873 (Toronto, 1914). By a journalist strongly sympathetic to Cartier but without a historian’s craft, this work leaves much to be desired, but for a long time it was the most complete study of Cartier. It was translated into French by Sylva Clapin and includes a fairly extensive bibliography. Chapais, Histoire du Canada, IV-VIII; by a historian of Canadian parliamentary life, these volumes cover the period 1833–67 and provide a good background to Cartier’s career. Alfred Duclos de Celles, Cartier et son temps (Collection Champlain, Montréal, 1913); a brief, rather laudatory biography. J.-L.-K. Laflamme, Le centenaire Cartier, 1814–1914; compte rendu des assemblées, manifestations, articles de journaux, conférences, etc., qui ont marqué la célébration du centenaire de la naissance de sir George-Étienne Cartier et l’érection de monuments à la mémoire de ce grand homme d’état canadien (Montreal, 1927). Rumilly, Hist. de la prov. de Quebec, I. The first volume in this long series deals primarily with Cartier’s influence on the government of Quebec, although he was then a minister in Ottawa. Benjamin Sulte, “Sir George-Étienne Cartier,” Mélanges historiques, Gérard Malchelosse, édit. (21v., Montreal, 1918–34), IV contains some interesting personal details on Cartier. j.-c.b.]

Cite This Article

J.-C. Bonenfant, “CARTIER, Sir GEORGE-ÉTIENNE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 2, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/cartier_george_etienne_10E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/cartier_george_etienne_10E.html |

| Author of Article: | J.-C. Bonenfant |

| Title of Article: | CARTIER, Sir GEORGE-ÉTIENNE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1972 |

| Year of revision: | 1972 |

| Access Date: | January 2, 2026 |