Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

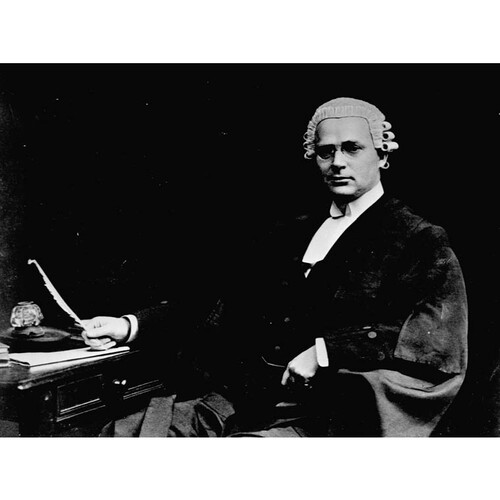

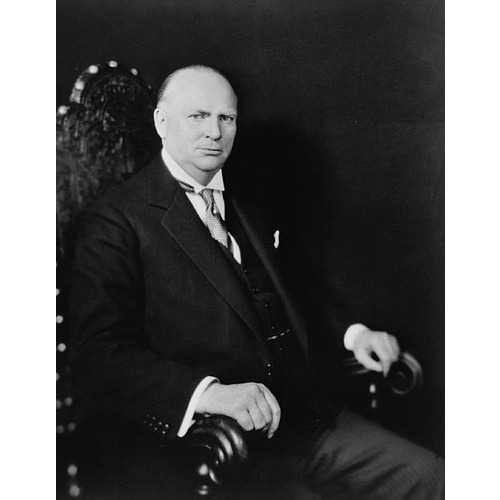

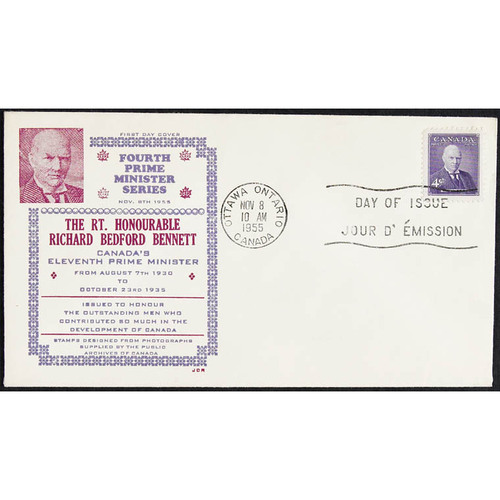

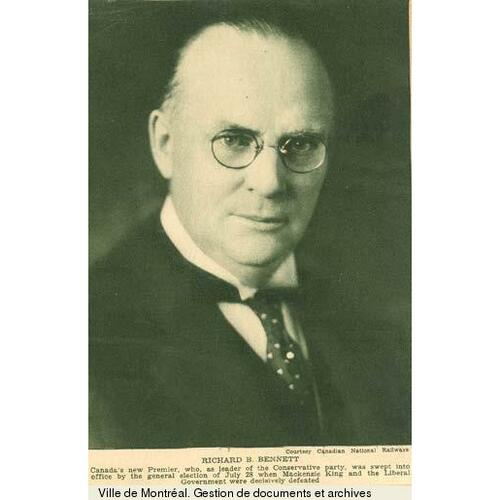

BENNETT, RICHARD BEDFORD, 1st Viscount BENNETT, lawyer, businessman, and politician; b. 3 July 1870 in Hopewell Hill, N.B., eldest of the six children of Henry John Bennett and Henrietta Stiles; d. unmarried during the night of 26-27 June 1947 near Mickleham, England.

The Bennett family came from England to Connecticut in the early 17th century. In 1761 they migrated eastward, part of a movement of New Englanders to take up old Acadian lands in Nova Scotia [see Robert Denison; John Hicks*]. The family settled first near present-day Wolfville and then moved across the Bay of Fundy to the estuary of the Petitcodiac in southeastern New Brunswick. There Nathan Murray Bennett, Richard Bedford Bennett’s grandfather, established a shipbuilding yard at Hopewell Cape. Henry Bennett, R. B.’s father, was apprenticed at age 20 to a relative to learn the shipping business. By 1868 he was a partner in the Bennett firm. On 22 Sept. 1869 he married Henrietta Stiles of Hopewell Hill, some eight miles west of the Cape.

Henrietta was a staunch Wesleyan Methodist, her husband an easygoing, occasionally bibulous, Baptist. Her stern teetotal Methodism became in her family the law supreme, its emphasis on work, diligence, and self-denial. Make sure, John Wesley had said, not to waste time on “silly unprofitable diversions”: “Gain all you can. . . . Save all you can. . . . Give all you can.” Bourgeois to the core, those lessons that Henrietta urged upon her first-born inculcated a way of life austere, sober, and hard-working. Charitable to the outer world, they could be exacting to the inner person. Self-indulgence was sin.

His mother also imbued him with ambition. Her aspirations for Dick, as the family called him, came probably from hopes frustrated by her husband and the difficulties of their shipyard. There were four children born between 1870 and 1876, just at the time when it was finding trouble. With increasing competition from iron hulls and steam engines, the shipyards of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia were being outclassed. Yards like the Bennett one had to content themselves with building schooners for the coastal trade. Those schooners would be around for many a year yet, but in the depression of the 1870s Henry Bennett’s shipbuilding was not enough to support his growing family; there were hints that he was an ineffective businessman. He had to turn himself into a general merchant, blacksmith, and farmer. R. B.’s penury started early. In 1934 he reportedly remarked to a friend, “I’ll always remember the pit from which I was [dug] & the long uphill road I had to travel. I’ll never forget one step.”

A small legacy his mother received allowed him at age 16 to attend Normal School in Fredericton, and he eked out a living as teacher at Irishtown, north of Moncton. He raised his licence to first class in 1888 and that autumn was appointed at age 18 as principal of the school at Douglastown, on the north bank of the Miramichi six miles downriver from Newcastle. Alma Marjorie Russell, then a schoolgirl, described him on his arrival, six feet tall, slim, freckled, sitting bolt upright on the wagon seat under a bowler hat too large for him, looking even younger than his age. He was a good teacher, able, firm, and fair. He liked to have his students memorize poetry, as he himself did all his life. His examinations were stiff going, but he was also prepared to criticize even the school authorities. His report of June 1890 noted that in his two years at Douglastown “I have not been favoured by a visit from one of the trustees.”

In his spare time he worked at Lemuel John Tweedie’s law office across the Miramichi at Chatham. By the autumn of 1890 he had saved enough to go to law school at Dalhousie University, Halifax. R. B.’s notes that first term include a poem, “The crossing paths,” that seems to have been of his own making.

As passing ships whose wide-flung sails

Are for an instant furled

We hail, and banter words of cheer,

Brought from the other world,

With eager question, quick reply

Across the deck we lean,

Then part and put the Silences

Of ocean wastes between.

At Dalhousie he plunged into work. His fellow students never saw him at rugby games; his interests were in the library, the moot court, debating. His record was sufficiently remarkable that when the dean of law, Richard Chapman Weldon, was later asked by Senator James Alexander Lougheed, a fellow Conservative, to recommend a good junior for his law office in Calgary, Weldon suggested Bennett.

After graduating in 1893, Bennett was back in Chatham in the law office now called Tweedie and Bennett. About 1895 there was a new office boy, William Maxwell Aitken* (the future Lord Beaverbook), at the age of 15 getting an early start on assorted mischief. In 1896 he persuaded a hesitant Bennett to run as alderman in the new municipality of Chatham; with Max for publicity on the Bennett bicycle, Bennett squeaked in by 19 votes out of 691. He received Lougheed’s invitation that same year, but he did not jump at it. Calgary was smaller than Chatham; Calgary was new, raw, untried; Alberta was not yet a province. There was the call of western opportunity to be sure, but there were also risks. In his mind, however, were (and would remain) Robert Browning’s lines “Ah, but a man’s reach should exceed his grasp, / Or what’s a heaven for?”

Bennett, tall, lean, and 26 years old, got off the train at Calgary in late January 1897. It was not an inviting place, -40 F with a hard wind, a skiff of snow holding down the dust of unpaved streets. The station had no cabs; Bennett lugged his bags over to the Alberta Hotel a block or two away. He was something of an outsider from the very first. Never one to follow the crowd, he neither smoked nor drank and he dressed formally at all times. He could work like a horse, long hours with no play. When some years later a friend sent him, along with New Year’s wishes, hopes for “a quiet mind,” Bennett replied, “Just why you should contemplate such a disaster I cannot understand.” Bennett’s was not a quiet mind: if amazingly retentive, it was an intensely restless one, his thought translated into action with enormous energy and by quick decisions.

The Lougheed-Bennett practice went slowly at first but by 1900 Calgary was growing and by 1905, when Alberta became a province, growing rapidly. Bennett was now buying and selling land, and with the firm’s retainer from the Canadian Pacific Railway, making a good thing of it. Calgary had become the centre of a large farming and ranching community. There were soon oil leases and oil companies as well. Bennett invested in William Stewart Herron*’s Calgary Petroleum Products Company, of which he became director and solicitor. Under manager Archibald Wayne Dingman* it struck oil in the Turner valley. Bennett also became involved with Aitken in the successful promotions that produced the Alberta Pacific Grain Company, Canada Cement, and Calgary Power. His reputation grew throughout, as an honest, versatile, clever, persistent lawyer. By 1914 he had an extremely busy and profitable practice. And R.B.’s teetotal principles would never obstruct legitimate legal business; among his clients was Alfred Ernest Cross*’s Calgary Brewing and Malting.

He was then well into Conservative politics. He had first been elected in 1898, as the member for West Calgary in the Legislative Assembly of the North-West Territories at Regina. There he challenged the view of the premier, Frederick William Gordon Haultain, a Conservative, that party politics had no place in the territories. After Alberta’s creation as a province in 1905, its capital at Edmonton, he was put forward by friends for the new Legislative Assembly. He lost, but was elected in 1909. In that contest the Liberals took 37 seats; there were 3 Conservatives and 1 Socialist. Of this unpromising opposition, Bennett was soon the spokesman, giving the government little quarter, especially in the matter of the Alberta and Great Waterways Railway contract [see Charles Wilson Cross]. He was a vigorous debater, not afraid of challenges, confident, perhaps too confident, of his own knowledge. In the subsequent litigation deriving from this issue that pitted the province against the Royal Bank of Canada [see Arthur Lewis Watkins Sifton], he acted for the bank and would ultimately be successful in 1913 on appeal to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council.

Bennett was that rare being, a successful Alberta Conservative, and was elected to the House of Commons for Calgary in 1911. His leader, Prime Minister Robert Laird Borden, gave him the honour of moving the address in reply to the speech from the throne. R. B.’s red Toryism was a little ahead of Borden’s, embracing workmen’s compensation, trade unions, government grain elevators, and government control of freight rates. As he put it in his maiden speech in the commons, 20 Nov. 1911, “The great struggle of the future will be between human rights and property interests; and it is the duty and the function of government to provide that there shall be no undue regard for the latter that limits or lessens the other.”

He had come to Ottawa feeling, however, that the party owed him more than just the address in reply. He had given up his CPR retainer of $10,000 a year the day after he was elected and there seemed to be few compensations. He could not be appointed to cabinet because Lougheed was government leader in the Senate. Three weeks after his commons speech he wrote to Aitken impatiently: “I am sick of it here. There is little or nothing to do & what there is to do is that of a party hack or departmental clerk or messenger.” But he believed in Borden’s Naval Aid Bill of 1912-13 and made a four-hour speech supporting it. He thought that the self-governing nations within the empire should be federated, that there must be recognition, as he had written to Aitken in 1910, “of common interests, common traditions, & above all common responsibilities and obligations.” “I hold out to this House” he said in the commons in 1913, “the vision of a wider hope, the hope that one day this Dominion will be the dominant factor in that great federation.” The Naval Aid Bill nevertheless foundered in the Liberal-dominated Senate.

As a new mp, Bennett was a maverick, his views on Canadian railways, tariffs, and Canada’s position within the empire not always conforming to party policy. His independence was starkly revealed in his opposition to the Canadian Northern Railway Guarantee Bill of 1914. His speech against his government’s financial support of this line was buttressed by wide experience and knowledge of railways. His targets included not only the railway and its principals, Sir William Mackenzie and Sir Donald Mann*, but Arthur Meighen, the solicitor general. Meighen was Borden’s bully boy whom the prime minister had given the job of piloting this complicated legislation. Meighen kept interrupting Bennett’s speech. Bennett did not like it: he was not going to have his argument broken up by “the gram[o]phone of Mackenzie and Mann.” Borden was uneasy about Bennett’s independence, but both he and Meighen recognized that Bennett’s long denunciation of the Canadian Northern was condemnation in detail of the most dubious of former Liberal prime minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier’s railway adventures.

When World War I came late that summer, Bennett tried to enlist, but he was turned down as not medically fit, for reasons that he never revealed. Then the sudden death of his mother, whom he had visited in New Brunswick each Christmas, supervened in October. His father had died in 1905, probably without much insurance, and it is reasonably certain that Dick supported his mother and Mildred Mariann*, the younger of his two sisters. The other sister, Evelyn Read, was about to be married to Horace Weldon Coates, a physician. They soon moved to Vancouver, where Dick bought them a house. Mildred followed them, and Dick’s next Christmases, 1915-27, would be spent on the west coast.

In July 1915 Borden invited Bennett as his assistant to London, to ascertain how Canada might help British military and civilian needs. The following year he was made director general of the National Service Board, charged with determining the number of prospective recruits in Canada. The war seriously affected his practice in Calgary, enlistments taking his political organizer, George Robinson, and several others from his office. The loss of these men, he told Max in London, “leaves me absolutely without assistance and heartbroken.” He then added a strange qualification: “so far as it is possible for a man of my type & temperment [sic] to be heartbroken about anything.”

What did that signify? He had been a devoted son, a dutiful and loving brother. Benevolence was an obsession; he was giving money to deserving students, needy widows, and a host of charities, altogether ten per cent of his gross income. What then were the springs of his nature? He loved hard work for the sheer satisfaction of mastery, in finance, accounting, law. He was a wizard with legal precedents and uncanny with errors in a balance sheet. At the same time he was a sublime egotist, clever, irascible, unsparing of himself or others. Forgiveness was one of the Christian virtues he found difficult to practise. He had a volatile temper, explosive while it lasted. Wound up in the coils of his own nature he seems rarely to have considered the effects of his words and actions. His receiving antennae were weak; sometimes they did not appear even to be deployed. R. B.’s limited receiving capacity was often the source of his strength and courage. His future rival William Lyon Mackenzie King’s sensitive antennae made him timid, his hypocrisy more crafty as he got older. Bennett scorned hypocrisy. He had the dangerous habit of saying what he really thought. What drove Bennett was his own mind, not what others might think of him.

Bennett supported the Military Service Act of July 1917, which was guided through the house by Meighen and which brought in conscription, but he opposed Borden’s idea of the Union government. He thought an alliance between Conservatives and Liberals, even for purposes of war, would end in disaster for his party. It did. Thus while in the election of December 1917 R. B. campaigned for the Conservatives, he did not run himself. In February 1918 he was further alienated by Borden’s failure to honour a promise Bennett believed the prime minister had made, to appoint him to the Senate. Borden chose instead an obscure Alberta Liberal, William James Harmer, to satisfy coalition arrangements. Bennett was furious. As for being senator, Bennett needed neither position nor money; his object was to put his knowledge and experience at the service of his country. He wrote Borden an aggrieved 20-page letter. There was no reply.

By 1918 Bennett had acquired a growing commitment to the E. B. Eddy Company of Hull, Que. This had developed from his long friendship with Jennie Grahl Hunter Eddy [Shirreff*], whom he had met in New Brunswick. After her husband, Ezra Butler Eddy, died in 1906, leaving her a controlling interest in his lumber company, she called on Bennett to help her manage her financial affairs. When she herself died in 1921, her will left 500 shares to Bennett and 1,009 to her younger brother, Joseph Thompson (Harry) Shirreff. Harry died suddenly in 1926, bequeathing all his shares to Bennett. They were now being assessed at $1,500 each, a valuation that made Bennett’s holdings worth $2,263,500. He thus became the principal director of the company. He kept watch on the firm but claimed an arm’s-length relationship, which most of the time it was. After Bennett had been given Mrs Eddy’s shares, there were rumours that there had been a romance between them. Some said that Mildred Bennett, born in 1889, was really their daughter. There was no truth in it. Bennett replied that when Mildred was born he had not even met Jennie Shirreff. As to romance, he said, Jennie was almost eight years older than he was, as if that were an impediment.

On 1 July 1920 Sir Robert Borden resigned, worn out with the war, Versailles, and politics. When the Unionist caucus chose Arthur Meighen as successor, many Liberals in it were already feeling the tug of ancient loyalties. Laurier had died in 1919 and the Liberals had chosen Mackenzie King as leader. In 1921 Meighen, with his majority crumbling, called an election for 6 December. To strengthen his government he asked Bennett to be minister of justice. Canada was in disarray socially and politically: a post-war recession, rising unemployment, continued labour unrest following upon the Winnipeg General Strike in 1919, industrial decline and discontent in the Maritimes, and an agrarian revolt on the prairies that had led to the formation at the national level in 1920 of the Progressive Party under Thomas Alexander Crerar*. Bennett decided to put his influence “on the side of law, order and constituted authority.” He was sworn in on 21 Sept. 1921. Soon enough he knew that there was little hope for the Meighen government. Bennett and his friends were also too confident of his own seat in Calgary West; the contest was so close that the outcome of a judicial recount depended on the way the X on the ballots was made. Bennett lost by 16 votes.

By March 1922 he was spending much time with the Eddy firm in Hull. He was thinking of giving up his 25-year old partnership with Lougheed. Sir James was 67 years old, was doing little work, and had been hiring juniors whose quality Bennett distrusted. He was seeing Lougheed about dissolving the partnership when a Privy Council appeal called him to England. Arrangements with Lougheed were left in suspense, but Sir James was persuaded that he could proceed with dissolution. His unilateral action set off irascible cables from Bennett, who indignantly bounced back to Canada. Thus began a messy litigation. The old Lougheed-Bennett firm split three ways, Bennett’s group, Bennett, Hannah, and Sanford, retaining most of the important clients, including A. E. Cross and fellow businessmen William Charles James Roper Hull* and Patrick Burns*.

By the mid twenties Bennett was extremely well off. His total income in 1924 was $76,897. Only 25 per cent came from his legal practice. His 1924 director’s fees, from E. B. Eddy and Alberta Pacific Grain mostly, totalled 7 per cent. The bulk of his income, 62 per cent, derived from dividends. Half of these came from Alberta Pacific Grain, of which he was president; he sold this firm to Spillers Milling of England late in 1924. Two other firms, E. B. Eddy and Canada Cement, represented 16 and 13 per cent of dividend income. The dividend portion kept growing. In 1930 he made $262,176, of which 85 per cent was dividends. That was the high point until 1937. Bennett was also a director of Metropolitan Life Insurance of New York and by the mid 1920s was on the board of the Royal Bank of Canada.

At the same time Bennett was being urged by Meighen to get back into politics. Going into the election of 1925 Meighen offered the justice portfolio should he be prime minister. Bennett threw himself into the campaign. He won Calgary West with a comfortable majority, and in Alberta his party gained three seats and 32 per cent of the vote. (The 1921 election had resulted in no seats and 20 per cent of the vote.) Across Canada the Conservatives took 116 seats, the Liberals 99. King was personally defeated in York North. It looked like a Liberal defeat, but King did not resign; he believed that with 24 Progressive mps he could carry on. It was dangerous going. Then came the customs scandal, an unholy mixture of rum, money, and bribery that began to unhinge King’s precarious coalition.

A select committee was set up to inquire into the administration of the Department of Customs and Excise, with Bennett and Henry Herbert Stevens* as the leading Conservatives. Its report, tabled in the commons on 18 June 1926, sharply criticized the former minister, Jacques Bureau*; Stevens, dissatisfied, moved for censure of King’s government. By this time Progressive loyalty to the Liberals was nearly gone. King, who had been returned to the commons at a by-election in Prince Albert, Sask., in February, managed to adjourn the house at 5:00 a.m. on 26 June by only one vote. That was when, to avoid the defeat of his government, he asked Governor General Lord Byng* for a dissolution. Byng refused, King resigned, and the King-Byng crisis was on.

Bennett had promised to go to Calgary to help provincial Conservative leader Alexander Andrew McGillivray* in an election. He tried to renege, but his Alberta friends held him to it. While he was gone, the new Meighen government was defeated by one vote, 2 July 1926, on an ingenious but spurious attack by King and James Alexander Robb on the legality of the acting ministers that Meighen had quickly appointed. Meighen did not, as yet, have a seat; Bennett was paired and in Calgary. Had Bennett been in the house, he would have been able to face down King, and Meighen almost certainly would not have been defeated. Meighen got the dissolution he had to ask for, with the election set for 14 Sept. 1926.

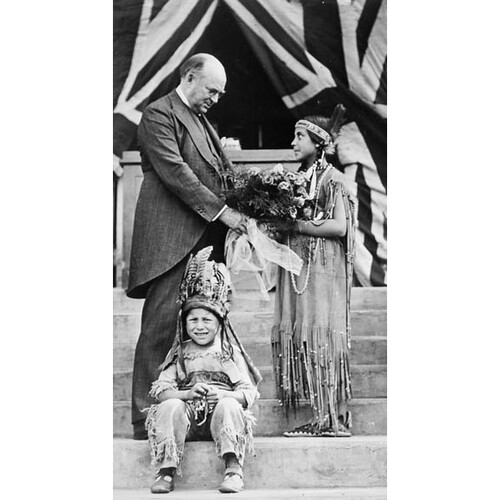

Immediately upon Bennett’s return to Ottawa he was sworn in to a clutch of portfolios: minister of finance, acting minister of mines, acting minister of the interior, and acting superintendent general of Indian affairs. Meighen expected to win the 1926 election with the customs scandal; King won it with an obscure constitutional issue made vital by the throb of Canadian nationalism that King put into it. Meighen was devastated. He resigned the Conservative leadership and caucus selected as temporary leader Hugh Guthrie*, a former Liberal who had joined Borden in 1917. It then called a convention to elect a new leader, to be held after the 1927 session of parliament.

One of the principal issues in 1927 was old age pensions, which Bennett strongly favoured. King had been hesitating about them for many reasons, not the least of which was the fact that existing war pensions, introduced by Borden’s government in 1919, ate up over 14 per cent of government expenditure in 1926. King had tried to bring in old age pensions that year, but the legislation had been killed in the Conservative-dominated Senate. In 1927 he reintroduced it, revised but still with weaknesses that Bennett thought unfortunate. The cost was still to be shared 50-50 with the provinces, though the provinces had not been consulted about the plan. “We are imposing our will upon the provincial legislatures,” Bennett said. He thought old age pensions should be funded wholly by Ottawa. He believed as well that the pensions should, like Britain’s, be contributory. Thrift in the form of pension contributions would thus earn its own reward. Those who could not afford such contributions would have them paid by Ottawa. In March, however, the bill as King presented it passed both the commons and the Senate, the upper house having apparently decided that the Canadian people had endorsed the scheme in the election.

Bennett was also an advocate of unemployment insurance and supported proposals put forward in the house that session by labour politician Abraham Albert Heaps*, though with conditions. Unemployment insurance should be funded by premiums paid by both the person concerned and the government, he argued. The subscription principle would encourage economy and industry. But Heaps’s proposals were voted down. Another major debate in 1927 arose over the administration of war pensions, mainly the narrow way entitlement was being viewed by the Board of Pension Commissioners. Bennett said the Pension Act was being handled too harshly, putting on the applicant the onus of proving his case. Bennett’s amendment won Progressive and Labour support; the government had to defeat it, which it did 95-78, but promised the act would be revised. Bennett’s contributions to the 1927 session well illustrate the forward thrust of his mind. “Shall we be statesmen or politicians?” he asked in one debate.

The Conservative convention opened in Winnipeg on 10 Oct. 1927. Various candidates were mooted. As late as the end of August, Bennett seems not to have entirely made up his mind whether he wanted to be leader. Some friends were trying to dissuade him, one contrasting “prestige, liberty, ease . . . delights, leisure” with “abuse, ingratitude, selfishness and slavish work.” Bennett was but 57 years of age, brimming with energy and ambition. Except for Robert James Manion, he was the youngest candidate. He was not concerned about ease or delights or prestige. There was such a thing as duty. Canada had been good to him. But as late as the day of the convention he may not have been fully decided. Then on the 13th he had a plurality on the first ballot and a majority on the second, rather to his surprise. His acceptance speech was sincerity and sentiment. He admitted being rich, but stressed that he had made his money from hard work. As elected leader, he would resign his company directorships. “No man may serve you as he should if he has over his shoulder always the shadow of pecuniary obligations.” Service to Canada would be his motto; out of Mark 9:35 he would be “servant of all.”

Bennett’s leadership of the party, prospective or real, induced offers to buy E. B. Eddy, all or part. Immediately after the convention he and Mildred went to New York and London. The Eddy match business, which had always been a headache, was sold to Bryant and May of London in December 1927, with a new entity called Eddy Match Company Limited established at Pembroke, Ont. Bennett retained a considerable block of Eddy Match stock. Eddy Pulp and Paper at Hull was more awkward to unload; Bennett would not accept any fire-sale price, and it was only in 1943 that it was sold to Willard Garfield Weston*. Bennett returned to Calgary late in 1927 to a flood of congratulations. He baled out of his many directorships as he had promised. “Must you?” asked Haley Fiske, president of Metropolitan Life, noting that Premier Louis-Alexandre Taschereau* of Quebec had kept his directorship in the company. Bennett insisted.

He had more pressing work now on hand. The state of the party was not promising. In Ottawa its national office was the back rooms of senior Conservative mps. It had no money; moreover, Bennett discovered that after what had happened in 1926, “it is exceedingly difficult to obtain money.” Newspaper support was unreliable. Across Canada there were only 11 dailies that could be called Conservative. Quebec Conservative papers had been devastated, as the party had been, by Borden’s and Meighen’s war policies. R. B. had been given authority by the Conservative convention to establish a central office in Ottawa. By February 1930, under national director Alexander Duncan McRae, there would be 27 full-time employees using modern office equipment to spread the Conservative word across the provinces. The money for this enterprise, and some provincial ones, came from Bennett and senior party members; they each put up $2,500 a month. More would be needed and by April 1929 Bennett had added a considerable chunk of his capital. By May 1930 he had contributed $500,000 since becoming party leader. About one-fifth went to Quebec.

In that province the Conservatives, French and English, were riven by faction, both communities apt to have more generals than soldiers. Bennett was urged to appoint a Quebec leader, but with so many groups he hesitated. He made a major speech in Montreal at a party banquet in October 1928, mostly in English, but with Quebec Conservative leader Arthur Sauvé, long estranged from Borden and Meighen, on the platform giving him warm praise. The party that in 1927 was described as “utterly helpless” was by the end of 1929 looking distinctly better. Some of the credit was owing to Conservative Ontario premier George Howard Ferguson’s repeal of repressive rules against bilingual schools, some to Sauvé’s successor, Camillien Houde*, and some to Bennett. In English-speaking Canada the situation was also fairly optimistic, with the Conservatives in power in five provinces.

The party’s fortunes had also been bolstered by Bennett’s considerable success as leader of the opposition. He went cautiously, Borden congratulating him on his excellent judgement and good results. After the session of 1928 ended he dutifully and energetically toured the constituencies, as he did again in 1929. He was not, however, without rueful reflections about his role: “Sometimes I wonder why I ever undertook this work at my time of life, after all my years of toil and effort.” In parliament his speeches were seldom marked with partisan venom. Bennett seemed rather to disarm enmity. The cheerfulness and charm with which the 16th parliament ended in May 1930 owed something to him. At dissolution, he and King shared a joke; mps flocked across the floor shaking hands. King remarked how pleasant it all was. And so the campaign of 1930 started.

Bennett left Ottawa at 2:10 a.m. on Sunday, 8 June 1930, in a private railway car attached to the Winnipeg train. He was glad to go; campaigning was hard work but in the capital that last week he had, as he told a friend, “been driven to death” by party demands of all kinds on the eve of a general election. Private railway cars were the way much electioneering was done. Radio was the big change from 1926. Bennett’s first campaign speech, out of Winnipeg on 9 June, was heard by Mackenzie King in Ottawa and by perhaps a million others. Bennett came over well on radio, having a resonant voice that carried better than King’s wheeziness. In 1926 there had been 134,000 radios in Canada; in 1930 they numbered close to half a million. Most operated by battery and did not require power lines, so the isolation of rural areas began to change. Radio also meant politicians did not need so many meetings. Nevertheless, from 9 June until 26 July Bennett travelled some 14,000 miles, delivering as many as five speeches a day.

There were not sufficient women candidates. Liberals were running women in hopeless constituencies simply to attract the female vote. Bennett wanted them in safe seats but was unable to persuade the constituencies. His sister Mildred campaigned with him. She had a remarkably deft political sense, as well as style, charm, empathy, and a sense of humour that often made up for her brother’s occasionally strident bluntness. She was a political asset in her own right and party officials were well aware of it. There were plenty of issues. After some years of steadily increasing prosperity, the stock market crash of 1929 and a collapse in the price of natural products had begun to undermine the Canadian economy. Wheat prices were down from $1.75 a bushel in July 1929 to below $1 a year later, causing great hardship in western Canada where the situation was worsened by drought and crop failure. Other agricultural areas contended with a flood of New Zealand butter. The malaise spread to the transportation and construction sectors and to the manufacturing industry, which began to experience lower prices and a decline in production and investment. Unemployment was greatly on the rise, and there was no security net. King’s angry assertion in April 1930 that he would not give any Tory government even a five-cent piece to help with joblessness was exploited by the Conservatives in cartoons and speeches. Bennett promised employment, through tariff protection for Canadian industries and a large program of public works. It was the issue that won him the election.

The result on 28 July 1930 was that the Conservatives won 137 seats against 91 for the Liberals and 17 others and a majority of seats in six of the nine provinces. The cabinet that he formed, 19 members in all, sworn in on 7 August, had able people, Guthrie, Stevens, Charles Hazlitt Cahan, Edgar Nelson Rhodes, and Edward Baird Ryckman*, but it was thin on similar French Canadians. Bennett himself took on Finance besides the portfolio usual to the prime minister, External Affairs (which he almost single-handedly saved from extinction, his caucus wishing to abolish it).

There would be a lot of cabinet meetings, proportionately almost double the number held by King. The oft-repeated story that Bennett was a tyrant in cabinet is, as Manion recalled, “just so much balderdash.” Most of Bennett’s ministers handled their departments without either his direction or his interference. In caucus it was much the same. Where Bennett did fail was in thanking cabinet colleagues in parliament or in public for things well done. In 1932 Manion would say to him, “My first ambition is that some day I may make a speech that will meet with your approval.” Bennett fairly fumed at this remark. But he telephoned the next day to make amends, though not apologies. R. B. hated to apologize. He was a critical taskmaster. He knew so much and hated to see questions incompetently handled; he found it difficult to praise those who did not meet his standards.

Bennett took office with action on his mind. Action he had promised and action Canada got. A special session of parliament was called for 8 September. He believed that tariffs were necessary not only to keep Canada independent of the United States but to create markets for Canadian producers, so tariff revision, steeply upward on a range of manufactured goods, was instituted. The emergency Unemployment Relief Act, providing $20 million for public works at the federal and local levels, was also passed. Parliament prorogued in two weeks. Then it was organization for the Imperial Conference in London, which was to start on 30 September and which Bennett hoped would provide a solution to Canada’s economic difficulties through the establishment of a reciprocal preference in trade. The conference was mostly a Canadian idea but Canadians would be a day late for it.

The composition of the Canadian delegation was a question in itself. Oscar Douglas Skelton, under-secretary of state for external affairs, came to Bennett about it. At first Bennett distrusted Skelton; he was too anti-British. “I’m not going to have you monkeying with this business,” Bennett was reported to have said. “It is for the Prime Minister’s office, not for External Affairs.” Skelton explained the role of External Affairs in imperial conferences under Borden and King, and a compromise was reached whereby John Erskine Read*, a legal adviser at External, was put on Bennett’s delegation.

At the second plenary conference at the Foreign Office in London on 8 October, Bennett came to the point. “I offer to the Mother Country and to all the other parts of the Empire, a preference in the Canadian market in exchange for a like preference in theirs.” The proposal was bold, blunt, and frank. It left the British government, committed to free trade, in shock. By that weekend the British papers were full of Bennett and Canada. “Empire or not?” asked the Observer (London). When the conference ended on 14 November there was still no answer. The real response came late that month in the British House of Commons when the rough-spoken James Henry Thomas, the dominions secretary, simply said that Bennett’s proposal was “humbug.” Nevertheless, when Bennett left London for Canada, Thomas was at Euston Station to bid him farewell. “On to Ottawa!” said Bennett as they shook hands. The conference would be renewed in the Canadian capital.

Bennett returned to an economic situation that was far more intractable than he had thought. Wheat prices had continued to drop and drought on the prairies was in its third year. Another series of tariff increases was instituted in 1931, and the Unemployment and Farm Relief Act was passed to provide funds for further public works as well as direct relief (more than $28 million would be spent and similar acts would be passed in 1932, 1933, 1934, and 1935). Bennett also began to try to find ways to help market the wheat crop, efforts that would culminate in the establishment of the Canadian Wheat Board in 1935.

In the later 1920s and early 1930s the Ontario school primers had a colour picture of the Union Jack under which was printed, “One Flag, One Fleet, One Throne.” By 1931 that neat logic was no longer quite tenable. “We no longer live in a political Empire,” Bennett declared after the adoption that year of the Statute of Westminster, which gave Canada and the other dominions autonomy in external relations. But he still hoped to construct “a new economic Empire.” He knew, however, that the “Empire Free Trade” being promoted by Beaverbrook in London was a chimera. His ideal continued to be an imperial preferential trade arrangement in which Canada would “play a part of ever-increasing importance.” The Imperial Economic Conference was supposed to have been held in Ottawa in 1931, but impediments had arisen and it had been put off until July 1932. Meantime Britain introduced a general tariff of 10 per cent, a development that gave some encouragement to Bennett’s hopes.

By the time of the conference Bennett had acquired much needed help in Finance. He appointed Edgar Rhodes as minister on 3 Feb. 1932. That spring he hired William Clifford Clark, professor of commerce at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ont., to prepare position papers. They were so useful that in October Bennett asked Clark to be deputy minister of finance. It was a brilliant appointment; Bennett was unerring in his judgement of able financial men. Nevertheless the Canadian civil service was weak to mount such an important conference. When the British were running them, the agenda had been circulated six months ahead. The Canadian agenda was ready only on 7 July, after the antipodean delegates had already sailed. The delay was also because, as Sir William Henry Clark, the British high commissioner in Ottawa, explained, “the Prime Minister is waiting as usual until he can find time to deal with matters himself.” During the conference Arthur Neville Chamberlain, Britain’s chancellor of the exchequer, would come to think “that the reason for Bennett’s difficulties is really inadequate preparation on his side. He has no professional civil service & no minister whom he trusts.”

When the conference opened in the Parliament Buildings on 21 July, Bennett was chosen to chair it. His opening speech suggested that Britain might have free entry into Canada for any products that would “not injuriously affect Canadian enterprise.” Only on 4 August, however, did the British get a list of Canadian concessions and it was much less than they expected. Bennett was subjected to many political pressures: his cabinet was deeply divided; he no longer quite trusted Stevens, his minister of trade and commerce; and there was intense lobbying by Canadian industrialists on cotton, coal, iron, and steel. Bennett did not want to wreck his own conference, but he and his cabinet colleagues believed that Britain was offering very little. Among the British representatives his reputation declined sharply. Walter Runciman, the president of the Board of Trade, became so annoyed with Bennett’s bullying manner that in mid August he warned him privately the conference was heading straight for failure and “the world would put the failure down to him.” Bennett had an aggressive style, he admitted it himself.

What emerged from the Ottawa conference was not any great imperial economic principle but hard-fought bilateral treaties. The British-Canadian one, as it turned out, benefited Canada more than it did Britain. Canadian wheat, apples, and other natural products got British preferences; the British got Canadian preferences for certain metal products and textiles not made in Canada. In a few years, Canadian exports to Britain were up 60 per cent; Britain’s to Canada were up 5.

One of Bennett’s constant advisers that summer was Major William Duncan Herridge. A lawyer and a former Liberal, he had broken with his party in 1926 and joined Bennett’s election campaign in June 1930. Mildred Bennett’s marriage to Herridge, now minister to Washington, took place on 14 April 1931. As she was packing up her things in the Château Laurier suite where she and R. B. had lived for nearly four years, she wrote a heartfelt note to “Dick, my dear dear brother.” It says much about them both: “If I could only say all that is in my heart but I can’t . . . in the midst of my most sacred and divine love you have never for a moment been out of my mind. . . . I sometimes think that loving Bill as I do - I’ve loved and valued you even more.” After Mildred had gone, R. B. seems to have become sharply aware of the huge interior space she had left vacant. “We’re the bumpers on his car,” Mildred had once remarked to Bennett’s long-time secretary, Alice Millar. “We save him from a lot of damage.”

On 21 Aug. 1932, as the Empress of Britain was sailing down the St Lawrence with exhausted British delegates aboard, Bennett was on his way to a restored 18th-century seigneurial house at Mascouche, Que. It was owned by Hazel Beatrice Colville of Montreal, the twice-widowed daughter of Sir Albert Edward Kemp, an old colleague of Bennett’s from the 1921 cabinet. Hazel, attractive, intelligent, and wealthy, was 43 years old, and her romance with R. B. had begun in April. Bennett went to Mascouche that summer whenever he could. Perhaps it was this intimacy that J. H. Thomas meant when he described Bennett’s private life as “very disreputable.”

Bennett’s relations with women have a strange history. He liked them, they liked him; he was tall, well-made, and rich. Why had he not married? The problem, according to one contemporary account, was phimosis, a tight foreskin that could be very painful at erection. That may well have been corrected by surgery during one of R. B.’s visits to London in 1905 or 1910. A more intractable difficulty seems to have developed by 1914, and may be the reason Canadian army doctors rejected him: Peyronie’s disease, a fibrous thickening of the penile shaft creating a distinct bend and at erection discomfort. It is a rare chronic condition of middle age and is sometimes related to incipient diabetes. What the effect of this was on Bennett’s affair with Hazel is guesswork. Certain it is that R. B. at age 62 was overwhelmed by the affair - “I miss you beyond all words & I am lonesome beyond cure without your presence,” he wrote. Then by 1933, certainly by 1934, it was over, ended by Hazel. She liked her life as a society woman, not least bridge, cocktails, cigarettes; Bennett disliked all three. There seemed to be lots of men; she did not need an exigent husband, however in love he might be.

Hazel may have been one reason why Bennett lacked time to prepare for the 1932 conference, but the House of Commons was another. The most urgent question there was radio. Canada was being inundated with American programs, hence American values. In December 1928 the King government had appointed a bipartisan royal commission, under chairman Sir John Aird*, to inquire into radio broadcasting. Its report the following September was a model of concision and decision. The text was nine pages. Radio, it maintained, had to be Canadian, English and French, but Canadian. Existing radio offered too much entertainment and not enough education. To these conclusions the leaders in the commons all subscribed, King, Bennett, and James Shaver Woodsworth, who headed the Labour group. The problem was how to put them into effect. Where lay the constitutional authority to regulate radio? Quebec claimed it fell within provincial jurisdiction. King had shied away from the question; Bennett acted as soon as he returned from London in December 1930. A reference was made to the Supreme Court of Canada and on 30 June 1931 it decided for the federal government. Quebec appealed to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council, supported by Ontario. Judgement was given in London on 9 Feb. 1932 in favour of Ottawa.

Within a week Bennett proposed a special committee of the commons. Everyone agreed, he said, that the present system was unsatisfactory. Radio was of surpassing importance, essential in nation building, and with a high educational value. The special committee reported on 9 May 1932 and the bill setting up the Canadian Radio Broadcasting Commission, to regulate all broadcasting in Canada and establish a nationally owned radio system, was presented a week later. In Bennett’s speech to the house on 18 May there was more than a touch of his red Toryism. Only public ownership could ensure to all Canadians the service of radio; no Canadian government was justified in leaving the airwaves to private exploitation. The House of Commons approved overwhelmingly the act setting up the CRBC.

The following year the country was facing even graver difficulties. Unemployment had reached 27 per cent of the workforce, as high as in the United States. On the prairies, drought, crop failures, and soil erosion continued, turning especially southern Saskatchewan into a dust bowl. The government’s budgetary deficit stood at $150 million and more than a million and a half Canadians were dependent on direct relief. The work camps for unemployed single men that had been set up in 1932 under the aegis of the Department of National Defence were becoming hotbeds of discontent. Everywhere established institutions seemed to be under threat. Bennett was doing the best he could to weather the economic storm; the problem was, as he told Sir Robert Borden, “that we are subject to the play of forces which we did not create and which we cannot either regulate or control.” People demanded action, but “any action at this time except to maintain the ship of state on an even keel . . . involves possible consequences about which I hesitate even to think.”

The pervasive feel of the depression was of this very helplessness. The lack of any vestige of hope exacerbated the climate of fear: fear induced by watching the old and familiar crumbling; fear that next month, especially next winter, there would not be enough to eat or the wherewithal to keep warm. Even for those on fixed incomes it was a distressing time, having to cope with tramps at the kitchen door and watching the freight trains going by with men riding to unknown destinations and for unknown purposes. Roots were drying up like the prairies. Borden told Bennett he and his wife fed everyone who came to the door at their Ottawa home. Two thirds of them, Borden said, were genuinely down on their luck, battered and bruised by economic forces over which they had no control.

By 4 March 1933, the day Franklin Delano Roosevelt was sworn in as president, almost every bank in the United States had locked its doors. The Canadian banking system had stood up well - there had not been a Canadian bank failure since 1923 - but there was urgent need of a central bank to regulate credit. Bennett had seen first-hand what the Bank of England could do to help Britain’s depression. On 21 March 1933 E. N. Rhodes announced there would be a royal commission on banking and currency in Canada. The commission reported in September, recommending three to two in favour of a central bank, the two dissenters being Canadian bankers. The legislation passed almost unanimously in 1934 and the Bank of Canada was established the following year with Graham Ford Towers* as its first governor. The chartered banks did not like it; they had to give up their profitable issue of bank notes in favour of a national currency, and they were required to transfer their gold reserves to the Bank of Canada. For the gold, they sought a much higher price than they had paid, a demand Bennett thought iniquitous. R. B. said to James Herbert Stitt, mp Selkirk, who asked about it, “his eyebrows bristling like quills . . . ‘Jimmie Stitt, you quit worrying. We are going to get that gold and it is just about time for us to find out whether the banks or this government is running this country.’”

There was other legislation in 1934. The Farmers’ Creditors Arrangement Act was designed to allow families to remain on their farms rather than lose them to foreclosure. The Natural Products Marketing Act established a federal board with powers to arrange more orderly marketing in the hope of obtaining better prices. The Public Works Construction Act launched a federal building program, worth $40 million, aimed at getting the unemployed back to work. A special committee (which later became a royal commission) headed by H. H. Stevens was set up to investigate mass buying by large businesses and the difference between the prices received by producers and the prices consumers were being charged. But Bennett considered the Bank of Canada his best domestic achievement.

Nevertheless, his government found the going difficult. “It may be too late,” Manion had reflected as early as 9 Dec. 1933, “to save the party from deluge.” In 1934 Conservatives lost provincial elections in both Ontario and Saskatchewan; they also lost four of five federal by-elections in September 1934. There were increasing doubts within the party that they could win a general election. Then in October the popular Stevens, having in the eyes of many in the cabinet overstepped the mark in his criticism of Canadian capitalists, was forced to resign his portfolio.

The Bennett New Deal of 1935, promising federal government intervention to achieve social and economic reform, arose from that political anguish. It was also genuine Bennett, policies he had espoused for many years, with roots in his own political instincts. He had long believed in old age pensions, unemployment insurance, and labour unions. What was new was the strong rhetoric devised by William Herridge and Bennett’s executive assistant Roderick K. Finlayson and delivered by Bennett in incisive radio speeches. “The old order is gone,” Bennett announced. “If you believe things should be left as they are you and I hold irreconcilable views. I am for reform. And, in my mind, reform means Government intervention. . . . It means the end of laissez-faire.” According to Manion, the New Deal speeches had not been discussed in cabinet. The centrepiece of Bennett’s program was the Employment and Social Insurance Act. It was followed by bills introducing a minimum wage, an eight-hour day, and a 48-hour work week. There were doubts about the constitutionality of these measures, but with elections due in a few months that was worth risking.

Herridge’s plan seems to have been to call parliament for mid January, goad the Liberals into denouncing New Deal legislation, and then dissolve late in February and go to elections. The strategy was thwarted by two things: King’s clever tactic of saying very little and, more to the point, Bennett’s illness. In February it was just a bad cold, but on 7 March atrial fibrillation of the heart was diagnosed. The doctors said he needed to rest for a month. His health was excuse sufficient that, had he chosen to retire then, it might have been managed. But the party would have had to select a new leader. The temporary house leader was Sir George Halsey Perley*, 77 years old, in voice and physique wasted and feeble; the leadership would probably have then devolved on H. H. Stevens, whom Bennett would not have had at any price. In Bennett’s absence more New Deal legislation was passed, especially the important Prairie Farm Rehabilitation Act, which set in motion a mighty enterprise that would eventually teach 100,000 farmers how to handle and restore the dust bowl in southern Saskatchewan. The house then adjourned in April.

Bennett went to England on 18 April to consult doctors and to take in George V’s silver jubilee. He returned to Ottawa a month later not much invigorated. The Canadian Wheat Board Act was then passed, as was a supplementary public works bill providing another $18 million for construction projects. Legislation was also approved to implement some of the recommendations of the price spreads commission, including the establishment of the Dominion Trade and Industry Commission to regulate business activity.

Bennett also had to deal with the On-to-Ottawa trekkers, a small army of the unemployed from the relief camps set up in 1932. The trek, begun in Vancouver, had been stopped by police in Regina. Delegates led by Arthur Herbert (Slim) Evans came on to Ottawa and met with Bennett on 22 June. It was not an amicable meeting. If Bennett was hard with the bankers of 1934, he was much more so with the trekkers of 1935, who threatened to disrupt law and order. The trek did not need to end the way it did, with a Dominion Day riot in Regina and a policeman killed and dozens injured; better communications between Ottawa and the Saskatchewan government might have avoided it. Bennett with his back up could be a chalcenterous animal.

Like many lawyers, Bennett distrusted public disorder. Strikes when legitimate he accepted, as disagreements inevitable over work or wages. But public law and order were to him fundamental. He hated the Communists with their too clever tactics at undermining the state. He himself was fearless and outspoken, able to face down and even convert a hostile crowd. There are many worse things in the world, Bennett would have said, than “Peace, Order, and good Government.” In his mind that was what Canada was all about.

Parliament prorogued on 5 July; Stevens, restless and dissatisfied, now quite at odds with Bennett, formed the Reconstruction Party two days later; parliament was dissolved on 15 August. Spurred by Stevens’s defection, and with desperate support from mps, his sister, and Herridge, Bennett fought a stirring campaign. But he was not sanguine, believing that Stevens had “crucified” the party. Bennett was indeed defeated on 14 Oct. 1935, but in terms of the popular vote it was not a massive defeat. From 1930 to 1935 the percentage of the Liberal Party’s popular vote actually decreased slightly. In 1935 the Conservatives still took 30 per cent. The Liberals really had no policy; they expected the depression would defeat Bennett and the depression did exactly that.

Seats in the House of Commons were quite another matter: the Liberals took 173, the Conservatives 40, and the other parties 32. The Reconstruction Party won only one, Stevens being elected, but their 8.7 per cent of the popular vote had cut deeply into Conservative seats. Stevens’s defection owed not a little to Bennett himself. Stevens and the wide sympathy that his price spreads commission evoked ought not to have been allowed to get away. The most popular politician nationally that the Conservatives had, Stevens should have been tolerated, even cosseted. Bennett was incapable of it. The Toronto Evening Telegram remarked about Bennett the day after the election, a “great statesman [was] defeated by a poor politician.”

For the next three years Bennett was a model opposition leader; indeed, government legislation was often improved by his interventions. In 1936 he was in the house almost every day, the most faithful of his party in his duty to parliament. Ostensibly he bore no grudges; he seemed to have accepted that the Canadian people who had suffered so much in the depression would want to punish the government. But he had given so greatly of himself, his energy, his health, and his fortune to captain the Canadian ship through that storm, he was hurt that so few Canadians seemed to be cognizant of his sacrifices. His charities, which were private, had become a huge burden. The requests he received in a single week “make life almost unbearable.” He estimated that in the years 1927-37 he had spent $2.3 million. His benevolence was in fact outrunning his income.

During the summer and autumn of 1936 he travelled to New Zealand, Australia, and South Africa. Back in Canada, he was introduced to a lively and likeable reporter from the Victoria Daily Times, William Bruce Hutchison*. Hutchison had seen Bennett at the fag end of the 1935 election campaign, backstage at a Victoria theatre, slumped, tired, a boisterous crowd ready to get at him. When Bennett came to speak he was transformed: his moral force, his booming voice, his sheer bravura triumphed over hecklers, over everybody. Hutchison had never seen anything like it. Bennett did the same with an even noisier Vancouver crowd the next night. Now in the spring of 1937 there seemed to be a newer Bennett, relaxed, his leg thrown casually over the arm of a chair in his office, talking almost continually about politics, Alexander the Great, Ming pottery, and the military geography of the South African War.

After the abdication of Edward VIII in December 1936 (”. . . speak / Of one that lov’d not wisely but too well,” Bennett quoted Othello in the House of Commons) Bennett and Mildred went to London for the coronation of George VI and then to a spa in Germany. He checked in at 228 pounds. Even for a man six feet tall, he was heavy; maple sugar and chocolates had taken their toll. His English doctor told him to lose at least 10 pounds to ease the strain on his heart. That autumn of 1937 Bennett discussed retirement, but the party persuaded him to carry on. By March 1938 he knew he could not continue. King could call an election any time and Bennett was now incapable of taking his party through it. He resigned on 6 March 1938, but stayed on until a new leader was chosen in July. There came a flood of appreciations for his work, including one from King; Bennett’s replies suggested that the compliments would have meant a great deal more to him had they come three to four years earlier, when the going was really difficult.

Then suddenly, on 11 May, Mildred, who was being treated for breast cancer in a New York hospital, died. Her death devastated Bennett; he shut himself up in her old room in their Château suite, consumed with grief, reading the Book of Ruth (“aught but death shall part thee and me”). She was only 49 years old.

The Conservative Party convention was held in Ottawa early in July. There was talk that Bennett wanted to be asked to carry on, but there is little firm evidence of it. There is strong evidence, however, that members of the party wanted him to make peace with Stevens and shake hands with him in public. Bennett was not having it. Robert Manion was chosen as leader; Bennett was not there.

Bennett had decided to live in England. In Canada he could have had positions from president of a university to president of a bank, but in Canada there were huge public pressures on his time and on his purse. He did not want to live in the United States; in London he was almost as much at home as in Canada. He went to England in August 1938 and on 1 November took over Beaverbrook’s option on Juniper Hill, a 94-acre property near Box Hill in Surrey. He proceeded to order those Canadian essentials, efficient plumbing and central heating. He then returned to Canada to take his leave. That proved to be much more difficult than he had imagined. His last farewell was aboard the Montclare in Halifax Harbour, on Saturday, 28 Jan. 1939. There was a luncheon aboard for 292; there were toasts and tears and Byron: “Fare thee well! and if for ever, / Still for ever, fare thee well.” He resigned his seat as mp Calgary West that day. The Montclare sailed in the evening.

Bennett came to love Juniper Hill. It was the only home he had ever had, and he acquired a devoted staff. He joined a host of organizations in England and was a popular speaker wherever he went. He seemed to be able to chair any meeting with grace and aplomb. As reward for his work as trouble-shooter at Beaverbrook’s Ministry of Aircraft Production, Winston Churchill offered him a viscountcy. Thus he headed the list of birthday honours for June 1941. He enjoyed the House of Lords and faithfully attended. He had had extensive first-hand experience of the British Commonwealth of Nations, and his presence in the Lords was felt and appreciated.

Lonely he was not. Garfield Weston in 1943 reported him “happy as a clam.” Most of the evidence runs that way. Two people, Beaverbrook and Thomas Clement Douglas*, thought him lonely, but their judgements were made perhaps after R. B.’s two nephews in the Canadian army were killed in Normandy in 1944. R. B. did find that hard. He was diagnosed with diabetes in 1944 too. But even in June 1947, Janice Amery had him to dinner at Eaton Square in London and declared him older “but happy and . . . so charming and interesting.”

He liked hot baths. He was warned to be careful, but late on Thursday evening, 26 June 1947, he neglected the warning; he died in his bath of a heart attack and was found there the following morning. The Mickleham church was crowded for his funeral, and there was a crowd too at the memorial service in Westminster Abbey on 4 July. He was buried in the Mickleham churchyard. Perhaps the best eulogy is the April 1938 letter from Harold Adams Innis*, professor of economics at the University of Toronto, when Bennett resigned the Conservative leadership: “Your leadership of the party especially during the years when you were Prime Minister was marked by a distinction which has not been surpassed. . . . No one has ever been asked to carry the burdens of unprecedented depression such as you assumed and no one could have shouldered them with such ability. I am confident that we shall look to those years as landmarks in Canadian history because of your energy and direction.”

Bennett lacked the common touch; he was too often in thrall to his own deeply held convictions. Although his charity was vast, his capacity for mercy was limited. Moral transgression he found difficult to forgive, whether in his brother George Horace, the ne’er-do-well father of an illegitimate daughter, or in H. H. Stevens, who had in Bennett’s view betrayed the Conservative Party. His inability to receive and absorb other people’s opinions and ideas made him strong and self-reliant but could also make him seem overbearing and self-righteous. His sense of humour was lively enough, but it never prevented him from taking himself too seriously. He was unable to laugh at himself. Though a statesman of note, he was a poor politician. But once out of politics, in England as the squire of Juniper Hill, he rose to an elegant maturity, hard-working, well liked, and respected.

No Canadian prime minister served Canada at greater personal cost, cost to his health and well-being, his own fortune, and even, be it said, his historical reputation. No Canadian prime minister deserved less the obloquy he received. He took Canada through the hardest years of the depression, and he did it with courage and determination. He put in place institutions and social policies that Canadians still have and still cherish. Despite his failings, perhaps he should be cherished too.

Bennett’s voluminous papers are in the Univ. of N.B. Library, Arch. and Special Coll. Dept. (Fredericton); they are available on microfilm at Library and Arch. Canada (Ottawa) (MG 26, K). Other useful papers at Library and Arch. Canada include the John Erskine Read papers (MG 30, E148), especially his “Reminiscences” in vol.10; the R. J. Manion papers (MG 27, III, B7), especially “Notes and memoranda” in vol.84; the Progressive Conservative Party of Canada fonds (MG 28, IV 2); and the J. R. H. Wilbur fonds (MG 31, D19). Also important are the Beaverbrook papers at the House of Lords Record Office (London) (Hist. Coll., 184), the Neville Chamberlain papers at the Univ. of Birmingham Library (Birmingham, Eng.), the Stanley Baldwin papers (MS.Baldwin) at the Cambridge Univ. Library (Cambridge, Eng.), the Hazel Colville papers (P030) at the McCord Museum of Canadian Hist. (Montreal), the E. N. Rhodes papers (MG 2, vols.404-21C, 562-88, 1099-205, 1216-19) at N.S. Arch. & Records Management (Halifax), and the P. B. Waite papers (MS-2-718) at Dalhousie Univ. Arch. (Halifax).

Library and Arch. Canada, MG 26, J13, 6, 30 May 1930 (the diaries of William Lyon Mackenzie King are also available online at king.collectionscanada.ca). Evening Telegram (Toronto), 15 Oct. 1935. Halifax Herald, 30 Jan. 1939. Manitoba Free Press (Winnipeg), 11-13 Oct. 1927. [W. M. Aitken], Lord Beaverbrook, Friends: sixty years of intimate personal relations with Richard Bedford Bennett . . . (London and Toronto, 1959). J. M. Beck, Pendulum of power: Canada’s federal elections (Scarborough, Ont., 1968). Can., House of Commons, Debates (Ottawa), 1911-21, 1926-38; Special committee on radio broadcasting, Minutes of proc. and evidence (Ottawa, 1932), 486-87. R. MacG. Dawson and H. B. Neatby, William Lyon Mackenzie King: a political biography (3v., Toronto, 1958-76). I. M. Drummond, Imperial economic policy, 1917-1939; studies in expansion and protection (London, 1974). Jacques Dumont, “Méditation pour jeunes politiques,” L’Action française (Montréal), 17 (1927): 28-40. L. A. Glassford, Reaction and reform: the politics of the Conservative Party under R. B. Bennett, 1927-1938 (Toronto, 1992). Roger Graham, Arthur Meighen: a biography (3v., Toronto, 1960-65. J. H. Gray, Men against the desert ([Saskatoon], 1967 [i.e. 1970]); R. B. Bennett: the Calgary years (Toronto, 1991). John Hilliker and Donald Barry, Canada’s Department of External Affairs (2v., Montreal and Kingston, Ont., 1990-95). Victor Howard, “We were the salt of the earth!”: a narrative of the On-to-Ottawa Trek and the Regina Riot (Regina, 1985). [W.] B. Hutchison, The far side of the street (Toronto, 1976). R. J. Manion, Life is an adventure (Toronto, 1936). F. W. Peers, The politics of Canadian broadcasting, 1920-1951 ([Toronto], 1969). Escott Reid, “The Canadian general election of 1935 - and after,” American Political Science Rev. (Menasha, Wis.), 30 (1936): 111-21. D. W. Smith, “The Maritime years of R. B. Bennett, 1870-1897” (ma thesis, Univ. of N.B., Fredericton, 1968). P. B. Waite, The loner: three sketches of the personal life and ideas of R. B. Bennett, 1870-1947 (Toronto, 1992). Ernest Watkins, R. B. Bennett: a biography (Toronto, 1963). John Wesley, The works of John Wesley, ed. A. C. Outler et al. (16v. to date, Nashville, Tenn., 1984-?), 2: 273, 279.

Cite This Article

P. B. Waite, “BENNETT, RICHARD BEDFORD, 1st Viscount BENNETT,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 17, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 2, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bennett_richard_bedford_17E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bennett_richard_bedford_17E.html |

| Author of Article: | P. B. Waite |

| Title of Article: | BENNETT, RICHARD BEDFORD, 1st Viscount BENNETT |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 17 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | April 2, 2025 |