Source: Link

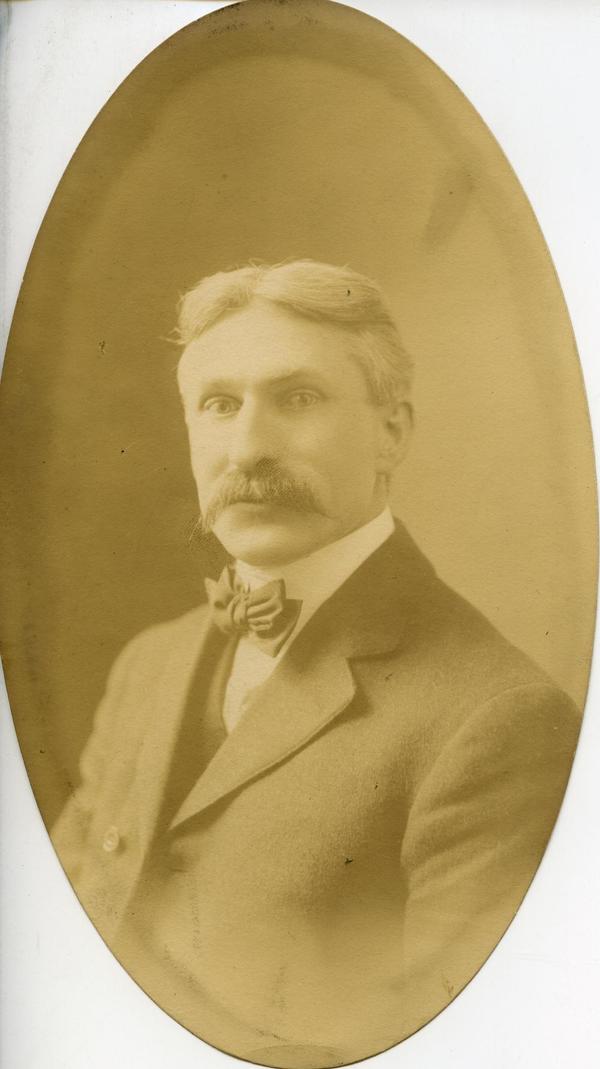

Mackenzie, Arthur Stanley, professor and university president; b. 20 Sept. 1865 in Pictou, N.S., son of George Augustus Mackenzie, a lawyer, and Catherine Denoon Fogo; m. 29 May 1895 Mary Lewis Taylor (d. 1896) in Indianapolis, Ind., and they had one daughter; d. 2 Oct. 1938 in Halifax.

A. Stanley Mackenzie was born into an Anglican family in the predominantly Presbyterian world of Pictou County, and had an upbringing that was a mixture, as he was later to say, of “religion, politics and porridge.” Educated at Pictou Academy as well as high schools in New Glasgow and Halifax, he came to Dalhousie University – the old Dalhousie on the Grand Parade in downtown Halifax – with a bursary in 1881. He took up the school’s tough regimen of Latin with John Johnson, mathematics with Charles Macdonald*, philosophy with Jacob Gould Schurman, chemistry with George Lawson*, and physics with James Gordon MacGregor*. The standards of teaching were high and the examinations unsparing. Young Mackenzie was a six-footer who loved sports and was on the school’s first rugby team; they played against Acadia College on 15 Nov. 1884 and lost by one point. As secretary of the new Dalhousie Athletic Club, Mackenzie penned a wry appreciation of Acadia’s victory: “You did nobly[,] Acadians…. And, although, it would have been an advantage to us if you had read the rules a little more carefully, and acted up to them a little more closely, yet we make no complaint.”

He graduated six months later with first-rank honours in mathematics and physics, for which he got the Sir William Young Gold Medal. After two years as assistant master at Yarmouth Seminary, he returned to Dalhousie as a tutor in mathematics and physics from 1887 to 1889. He then went to Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Md, for his phd, which he would receive in 1894. In 1891 he had been appointed lecturer in physics at Bryn Mawr, the Quaker women’s college near Philadelphia. He was rapidly promoted and would be a full professor by 1897. In 1895 Mary Lewis Taylor, whom he had met at Bryn Mawr, had become his wife. Their brief marriage ended sadly; she died in 1896 giving birth to their daughter. She had remarked, in a strange and prescient way, “You won’t marry again.” He never did. Mackenzie buried her in Indianapolis and took little Marjorie to Bryn Mawr, raising her as best he could. He tried to make her life a happy one, and she came to share his fishing trips, his curling, and his golf.

In 1900 Mackenzie published The laws of gravitation …, and he later spent a year at the Cavendish Laboratory at the University of Cambridge, where he was working on particle physics. He published an important paper on the alpha rays of radium (of which he was the first to measure the mass and velocity) and polonium in 1905, inspiring this verse in a Cambridge song:

Electrometers get in a frenzy

When quietly by them I lay,

So they sent me downstairs with Mackenzie

Who’s wanting my last alpha-ray.

That same year Dalhousie invited him to be George Munro professor of physics. Although he well knew Dalhousie’s weakness in scientific facilities and equipment, Mackenzie was glad to return to Nova Scotia. He was a gifted teacher and loved teaching. Yet he loved research even more, so when in 1910 the Stevens Institute of Technology in Hoboken, N.J., offered him a research post, he could not resist. There was sadness at Dalhousie, and the school’s affection for him comes through in a jocular poem by Archibald McKellar MacMechan, George Munro professor of English since 1889:

Farewell to Mackenzie, farewell to the Prof.,

Who can mingle his Physics and fishing and Goff

With a drop of the liquid that betters the score,

And we hope he’ll return to Our City once more.

Mackenzie soon did. Early in 1911 the Dalhousie board of governors bought the Studley estate [see Elizabeth Carey*]. It was an ample 43-acre site located above the Northwest Arm, amid pines, red oaks, and willows. At last, said Mackenzie, Dalhousie’s “long-delayed marching orders had arrived.” The board of governors now invited him to succeed John Forrest* as president, at a salary of $3,600 per year. He accepted. He would be in Halifax for the rest of his life.

His regime began on 1 July. Plunged at once into a vast range of problems, Mackenzie tackled them personally as Dalhousie presidents had always had to do. He started with the administration of his office. During Forrest’s tenure it used to be said that the university’s office records were on the starched cuffs of the president’s shirts. Dalhousie had got its first typewriter only in 1907. A professional secretary was hired, and by 1913 a system of documentation was emerging. Mackenzie also undertook a major fund-raising campaign, the Dalhousie Forward Movement, and set out in May 1912 to meet with Dalhousie alumni and appeal for donations. By October he had collected $444,891, much of which would help fund the creation of the new Dalhousie campus.

Mackenzie liked the old Georgian style of buildings such as Government House and the House of Assembly. Frank Darling*, the Toronto architect hired to oversee the construction project, did too. The first edifices, the Science Building and the Macdonald Memorial Library, were completed by 1915. With post-war enrolment at 622 in 1919, the school’s population was double that of the previous year, and the campus was awash with students male and female. The board of governors approved a decision to build a women’s residence, and as soon as the ground had thawed that spring, Mackenzie set out, with Professor of Engineering John Norison Finlayson and a six-foot crowbar, to check how deep the soil was at the best location. The problem there, as everywhere else in the city, was the ubiquitous hard Halifax ironstone; mercifully, it was not close to the surface, for the site that had been chosen, with tall white pines that overlook the Northwest Arm, was lovely. There came hints from one of the Dalhousie governors, Richard Bedford Bennett*, that a widow who was a former Halifax resident might be interested in funding the dormitory. In March 1920 Mackenzie went to Ottawa to meet Jennie Grahl Hunter Shirreff*, the widow of Ezra Butler Eddy*. A woman of ideas and decision, she lived in eccentric modesty in the Russell House. Within eight weeks she had offered $300,000 for the structure, which would be named Shirreff Hall [see Eliza Ritchie].

Soon Mackenzie would face the most difficult issue of his time as president: university federation. The matter had a long and tortuous history. The first post-secondary institution in Nova Scotia was King’s College, chartered in 1802. Established in Windsor as a bastion of the Church of England, it was deliberately built 40 miles from the wickedness and garrison glitter of Halifax. Lord Dalhousie [Ramsay*] in 1818 intended that his non-denominational college would be set in the middle of Halifax and would therefore be, like his alma mater, the University of Edinburgh, accessible to everyone. There had been three previous attempts to merge Dalhousie and King’s, as well as movements to unite all the province’s colleges in the 1840s and 1870s. But Nova Scotia and its legislature were fractured with sectarian rivalries between Baptists, Methodists, Presbyterians, Roman Catholics, and Anglicans, and most disliked intensely the idea of merging the colleges into a single, officially godless college at Dalhousie.

The Carnegie Corporation of New York, having had a plethora of requests from Maritime colleges for support for every shape and size of worthy cause, in 1921 sent William Setchel Learned and Kenneth Charles Morton Sills, respectively an official with the foundation and the president of Bowdoin College in Brunswick, Maine, to inquire into the state of higher education in New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island. The report, fair-minded and cool, was produced quickly. It gave high marks to Mackenzie’s Dalhousie, though the school’s serious weaknesses in libraries and laboratories did not escape criticism. Learned and Sills recommended that all post-secondary institutions in the Maritimes be federated, and the new university be located on the big new Dalhousie campus. Carnegie offered $3 million to facilitate the process; it was presumed that Acadia, Mount Allison, Dalhousie, St Francis Xavier, King’s, and the University of New Brunswick would be involved, and that smaller schools, such as St Dunstan’s in Prince Edward Island, might merge with larger denominational colleges. Mackenzie inevitably played a central part in discussions, and with one aim in mind: to improve university education in Nova Scotia, and possibly at the same time in New Brunswick and P.E.I. Integral to this goal was his belief that federation “would bring state aid” to Nova Scotia’s post-secondary institutions, which at the time received no government funding. Much of 1922 was taken up with the hard, often dreary work of conferences, committees, and compromises. Mackenzie complained to University of Toronto president Sir Robert Alexander Falconer* that the other college presidents would profess their acceptance of the principle of federation, but when it came to a binding decision would vote against what they had previously accepted. He described some of them as “slippery and hypocritical tricksters” who drove Dalhousie’s representatives “to the very limit of endurance.” The other colleges feared Dalhousie’s imperial reach, with its medical school, its law school, and its officially non-denominational enrolment, but there was the temptation of that Carnegie money. The only things imperial about Mackenzie were his physical stature, his dignity, and his patience. In February 1923 Acadia followed the path already taken by the University of New Brunswick and St Francis Xavier and baled out of the discussions; this effectively killed the substance of the plan. Only King’s, strapped for funds after a fire in 1920 destroyed its building, came to Halifax.

Not all university presidents are loved by their constituency, yet Mackenzie was. He was cool, quiet, and strict in his sense of duty. He hated humbug and pretence and self-advertisement. His advice to new members of staff was one word: “Work!” Those stern Latin imperatives in Dalhousie’s motto, Ora et labora (pray and work), were to be taken to heart. He had been brought up to follow the old, steep, lonely path to learning and he trusted in it, but he approached it with an instinctive canniness and caution. There was a democracy among Dalhousie’s staff that emanated from its history and its professor-centred constitution, but also from its president. In 1927 MacMechan, his long-time colleague and golfing rival, after almost four decades of teaching at Dalhousie, wanted out of the boring job of invigilating examinations, a three-hour-long chore. Mackenzie said, in effect, that he could not get out of the task: it was one they all had to do. In his letter he added: “I hope the time will never come … when I shall feel superior to attending to the miserable, petty, time-consuming little details and jobs that come before me every day.”

In December 1930 Mackenzie, now aged 65, announced to the board of governors his decision to retire. He did not want to wait until his departure would be greeted with sighs of relief. “I’m afraid,” he told his colleagues, “that would finish me.” So saying, he handed his resignation, effective 31 July of the following year, to the secretary and walked from the room. Every member stood up as he left. They then made the five-minute walk to the president’s house – bought for Dalhousie in 1925 by alumnus R. B. Bennett – where they drank scotch and commiserated over age and time and change.

Mackenzie, in hospital for minor surgery, died suddenly of a stroke on 2 Oct. 1938. The whole university turned out for his funeral three days later. His body was escorted to the train station so that he could be reunited with his wife in the Indianapolis graveyard. There were eulogies from professors, students, and university and college presidents across Canada. The student paper, the Dalhousie Gazette, had a full issue about him on 20 October. Walter Charles Murray*, the Nova Scotian who headed the University of Saskatchewan, declared that “Mackenzie was responsible for the transformation of a small college into a national university with buildings of great beauty.… [He was] kingly in presence, outlook, and leadership.” Mackenzie worked to raise Dalhousie and its students towards standards of learning and aspiration recognizably international; he seems never to have lost the hope that learning and even more the love of it would mark a student from his Dalhousie University.

Arthur Stanley Mackenzie is the author of numerous scientific articles, including “On the attractions of crystalline and isotropic masses at small distances,” Physical Rev. (College Park , Md), 1st ser., 2 (March–April 1895): 321–43 and “LXI. The deflexion of α rays from radium and polonium,” Philosophical Magazine (London), 6th ser., 10 (1905): 538–48; he also translated and edited The laws of gravitation: memoirs by Newton, Bouger and Cavendish: together with abstracts of other important memoirs (New York, 1900).

DUA, UA-3 (president’s office fonds), box 96, file 25 (Archibald MacMechan personnel record); box 326, file 4 (Mackenzie to Sir Robert Falconer, 3 Nov. 1922); UA-33 (student union/student organizations fonds), box 7, file 6 (minutes of the Dalhousie Athletic Club). Private arch., P. B. Waite (Halifax), Interview with Janet MacNeill Piers, 17 Sept. 1992. UTARMS, B1972-0001/013(03). Cavendish Laboratory, The post-prandial proceedings (Cambridge, Eng., 1905). W. A. Craick, “How personality creates: the task of President A. Stanley Mackenzie of Dalhousie University,” Maclean’s (Toronto), December 1913: 21–24. A. McK. MacMechan, Late harvest (Toronto, 1934). W. C. Murray, “Stanley Mackenzie of Dalhousie,” Dalhousie Rev. (Halifax), 18 (1938–39): 427–34. P. B. Waite, The lives of Dalhousie University (2v., Montreal and Kingston, Ont., 1994–98).

Cite This Article

P. B. Waite, “MACKENZIE, ARTHUR STANLEY,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 31, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mackenzie_arthur_stanley_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mackenzie_arthur_stanley_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | P. B. Waite |

| Title of Article: | MACKENZIE, ARTHUR STANLEY |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2016 |

| Year of revision: | 2016 |

| Access Date: | December 31, 2025 |