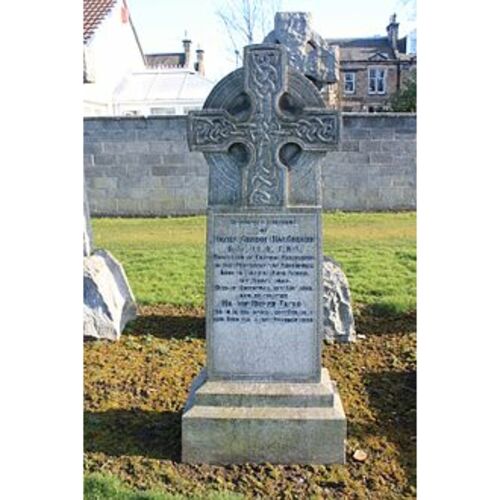

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

MacGREGOR, JAMES GORDON, professor; b. 31 March 1852 in Halifax, son of the Reverend Peter Gordon MacGregor and Caroline McColl; grandson of the Reverend James Drummond MacGregor*; m. 1888 Marion Miller Taylor of Edinburgh, and they had a son and a daughter; d. 21 May 1913 in Edinburgh.

James Gordon MacGregor was educated in Halifax at the Free Church Academy and Dalhousie University, from which he received a ba in 1871 and an ma in 1874. He went to the University of Edinburgh on scholarship in the latter year and did natural philosophy (physics) there, in Leipzig, Germany, and at the University of London, where he took his dsc in 1876. He returned to Dalhousie in 1877, becoming lecturer in physics, and, in 1879, George Munro professor at the age of 27.

MacGregor was brilliant, energetic, nervous, impatient. He was not willing much to suffer fools. In a senate meeting, when some colleague was blundering about a rule he would smile and say, “Read your calendar.” Work was his element. Afflicted from youth with a bad heart, he drove himself, in classroom and laboratory, in season and out. He found it hard to take a holiday. One he did take was with Professor William John Alexander*, climbing Mount Washington, N.H. To his science and his students he gave most of his intense and blazing energy.

He was a born researcher, gifted with a singularly alert mind. He had little equipment at Dalhousie to work with, but from his laboratory, making do with much homemade apparatus, he produced some 50 papers, mostly on kinematics and dynamics. They earned him charter-membership in the Royal Society of Canada and membership in the Royal Society of London. Physics was, he believed, next to literature the best of all subjects for a general education, since it brought the student up against the fundamentals of science. In the 1880s he led a successful attack on the old Dalhousie regimen of classics and mathematics to broaden it and make it more flexible.

Having devised often enough his own laboratory equipment, MacGregor declared that failures were the best school of success. It was perhaps this fundamental difficulty over the proper equipping of a good laboratory that led him early to the conclusion that the only way Nova Scotia could put its young men and women on the same footing as those of McGill and Toronto was by consolidation of what he regarded as the weak, poorly endowed colleges into one well-equipped university. He led every movement to this end, urging King’s College to join Dalhousie in 1884 and 1885 and expressing enthusiasm over a similar effort in 1901. He spent his summers in the University of Edinburgh laboratory of Professor Peter Guthrie Tait.

It was to Tait’s chair of natural philosophy at Edinburgh that MacGregor succeeded in 1901. He found the invitation impossible to resist: salary better, equipment good, pension laid on. But he said later that it was the absence of the last at Dalhousie, remedied in 1906, that had persuaded him to go. For he was fond of his Dalhousie colleagues and hated to leave them. He wrote Professor Archibald McKellar MacMechan* a sad letter from London on his way north to Edinburgh in September 1901: “There are some things a man can’t say to a man face to face. But now that[?] the ocean is between us I feel impelled to tell you how deeply I regret that this translation to Edinburgh must separate us & how much your friendship meant to me in the years we have had together. . . . Don’t let the pessimists dishearten you. The day of better things must come.”

MacGregor was a radical in spirit, disliking rules and regulations almost on principle. He hated sham and humbug, and that comprehended petty university regulations. He was often on the side of Dalhousie students when various misdemeanours came before senate. They should have room, he believed, “to play the fool,” though if they broke rules they should pay for their fun. He found those sympathies strained by the rough student manners at Edinburgh.

There he had a battle getting accepted the principle that all physics students should have laboratory classes. It was not yet the norm in Scotland; MacGregor thought it essential. He set to work to realize it, getting authority and the money to do so. None of it was easy. The laboratory, when finally ready, would accommodate 40 students; there were 250 applicants.

What MacGregor missed at Edinburgh was the freedom and flexibility of Dalhousie. When in 1904 his former student Arthur Stanley Mackenzie* was getting fed up as professor of physics at Bryn Mawr College in Pennsylvania and was considering an offer to return to Dalhousie, MacGregor wrote a bit wistfully: “I often sigh for [Dalhousie] here – complete freedom in regulating one’s course, making improvements, laying new plans – old friends to deal with, a fine body of students to teach &c. . . . So far [here] my whole time has been taken up with routine work & I see little prospect of improvement unless the new laboratory brings an additional assistant which is not likely. . . . I sigh for the old Dalhousie days from this point of view and others as well. . . . And after all we have but one life to live & it is a great matter that one’s daily associations should be characterized by sweetness & light rather than nagging & disagreeableness.” Bigger fields are not always greener.

On the morning of 21 May 1913 MacGregor was in his room dressing, felt ill, called his son, but died almost at once. He was 61.

James Gordon MacGregor’s publications include An elementary treatise on kinematics and dynamics (London and New York, 1887) and numerous other scientific reports, most of which are itemized in Science and technology biblio. (Richardson and MacDonald).

No MacGregor papers have as yet been discovered, but there is correspondence from him in both the A. McK. MacMechan (MS 2-82) and the A. S. Mackenzie papers (MS 2-43) at Dalhousie Univ. Arch. (Halifax). Obituaries of MacGregor are found in the Edinburgh Scotsman and in the Halifax Daily Echo, Halifax Herald, and Morning Chronicle of 22 and 23 May 1913.

Dalhousie Univ. Arch., MS 2-43, box 1, MacGregor to Mackenzie, 3 Aug. 1904; MS 2-82, box 3, MacGregor to MacMechan, 9 Sept. 1901. Dalhousie Gazette (Halifax), September 1912, September 1913. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898 and 1912). Standard dict. of Canadian biog. (Roberts and Tunnell). Wallace, Macmillan dict.

Cite This Article

P. B. Waite, “MacGREGOR, JAMES GORDON,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 14, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/macgregor_james_gordon_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/macgregor_james_gordon_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | P. B. Waite |

| Title of Article: | MacGREGOR, JAMES GORDON |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1998 |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | December 14, 2025 |