Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

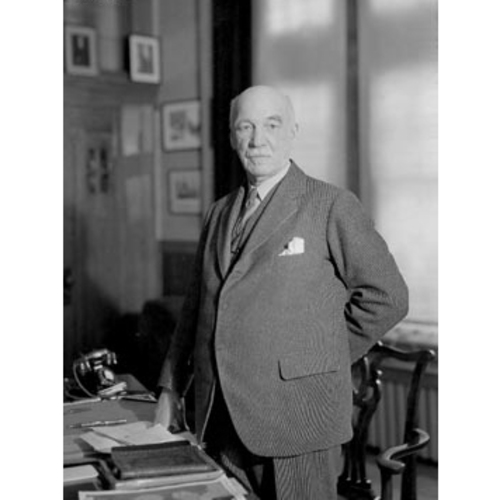

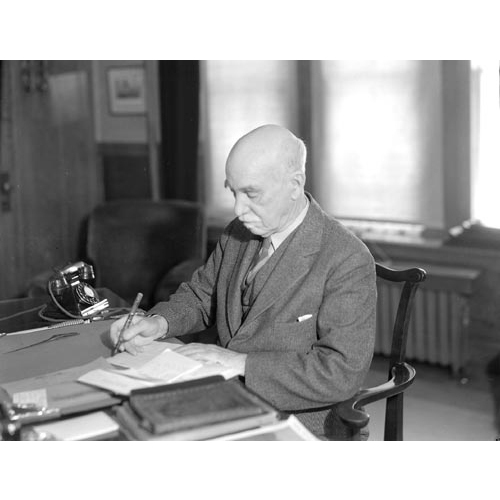

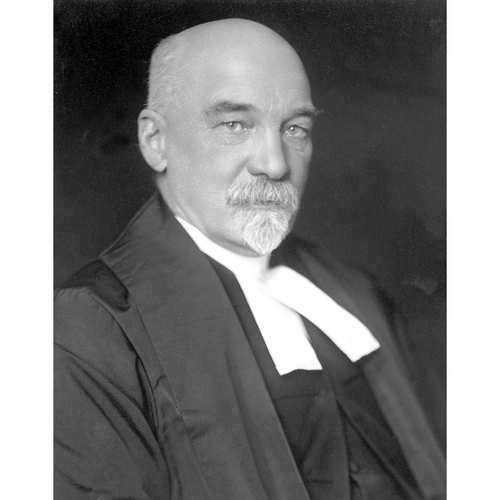

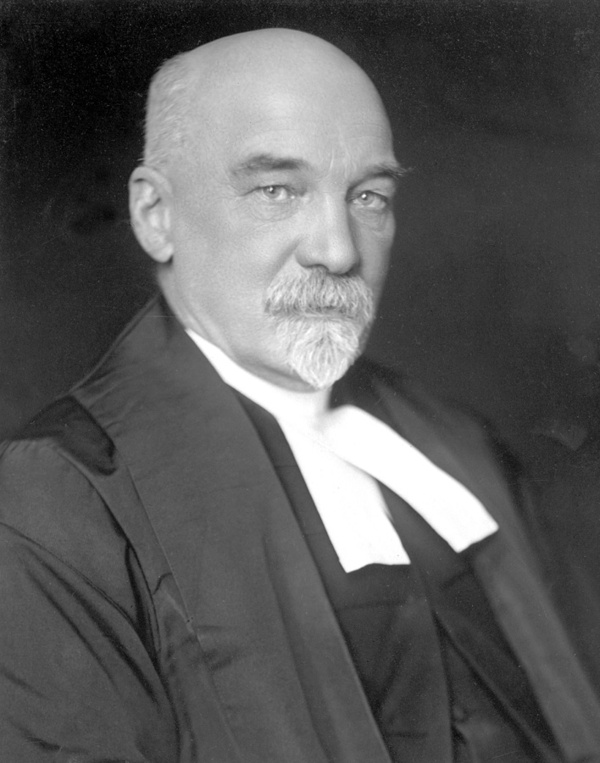

WALSH, WILLIAM LEGH, lawyer, politician, sportsman, judge, and office holder; b. 28 Jan. 1857 in Simcoe, Upper Canada, son of Aquila Walsh* and Jane Wilson Adams; m. first 14 Nov. 1883 Bessie Amelia McVittie (d. 2 Sept. 1925) in Barrie, Ont., and they had a daughter and a son; m. secondly 22 April 1931 Bertha Main Barber, née Cassady (d. 20 Aug. 1943), in Vancouver; d. 13 Jan. 1938 in Victoria.

Of loyalist descent, William Walsh’s father sat in the Legislative Assembly of the Province of Canada and after confederation in the new dominion’s House of Commons. He ended his public career in Winnipeg as commissioner of crown lands. William, who attended public and high school in Simcoe, studied law at the University of Toronto and Osgoode Hall. Called to the Ontario bar in 1880, he first practised in his hometown and the following year he moved to Orangeville. He recognized the importance of thoroughness in researching and presenting a case and displayed marked analytical power in unravelling the tangles and intricacies encountered in litigation. During his 19 years in Orangeville, he took a special interest in business, civic affairs, and sports, as well as the law. For three years he served on the public-school board, including a term as chair, and in 1891–93 and 1899–1900 he was mayor. In the federal election of 1896 he was the unsuccessful Conservative candidate in the surrounding constituency of Cardwell. An avid cricket player, he was also a member of the famed Orangeville Dufferins lacrosse team.

Lured by gold-rush fever, Walsh moved to the Yukon Territory in 1900, was called to the bar there that year, and established a practice in Dawson. Although he arrived after the rush had peaked, there was still plenty to engage him personally – he took up curling – and professionally. As a lawyer, he earned his largest cheque ever in the Yukon, though when he left he claimed he had less money than when he arrived because of his wildcat investments in gold-mining properties. Despite his energetic work for the Conservatives, in 1903 the Liberal government in Ottawa named him a kc in recognition of his able legal contributions. The same year he ran for the position of mayor of Dawson.

Defeated in this bid and facing the economic decline of the north, Walsh accepted the invitation of a transplanted law associate from Orangeville, Maitland Stewart McCarthy*, and in 1904 he moved to Calgary to join him in a legal partnership. Once more Walsh became busy in his new community. He walked and golfed to remain fit. Active in the Church of England, he would serve as chancellor of the diocese of Calgary from 1927 to 1931. He continued his political involvement, as founding president of the Alberta Conservative Association in 1905 and head of the Calgary association. It was in this circle, and in the courts, that he came to know Richard Bedford Bennett*, a local lawyer with political aspirations. In 1906 Walsh unsuccessfully contested the provincial by-election in Gleichen. Though never a candidate again, he was an organizer in the federal election of 1911, which the Conservatives won.

Following this election and eight years of practice in Calgary, Walsh secured an appointment as a judge of the Supreme Court of Alberta on 3 April 1912, a position he had coveted. On 27 Jan. 1931 he was named to its appellate division. He travelled over much of the province to hear cases. Like other early Alberta judges, including Nicholas Du Bois Dominic Beck*, he enjoyed the research side of his work, and together they helped build a body of western precedents. According to veteran lawyer James Short, he “never allowed cases or counsel to lag” and his addresses to juries were “models of clarity.” Wanting to maintain close ties with Britain, in 1931 he opposed the idea of abolishing appeals from Canada to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in London. These appeals would continue until 1949.

Walsh’s election in 1907 as a founding bencher of the Law Society of Alberta had confirmed the high esteem in which he was held by his peers. To friends, he was “Daddy” Walsh, a judge who followed the best British traditions and ran his court with dignity and compassion. However, he also became known as a hanging judge for his sentencing of 18 individuals to be executed for murder. Capital punishment, Walsh believed, was a “valuable deterrent” to crimes of violence. His most interesting case, he once told a reporter, was the Picariello–Lassandro murder trial of 1922, one of the several he conducted that aroused national and international attention [see Filumena Costanzo*].

With Walsh’s commendable record as a jurist and chair of a number of provincial inquiries, Prime Minister R. B. Bennett recommended that he be appointed lieutenant governor of Alberta, effective 5 May 1931. During his tenure he fought with the government over the upkeep of Government House in Edmonton, and he became associated with a minor constitutional issue. When Premier John Edward Brownlee* resigned in July 1934, because he had become caught up in a nasty civil action as the defendant in the alleged seduction of a young woman, he did not name a successor. The government caucus then met and chose Richard Gavin Reid*. Walsh refused to accept this decision until Reid had proved his ability by forming a cabinet, which he soon did. Walsh served as lieutenant governor until 1 Oct. 1936. Among the honours bestowed on him during his time in office was a chiefship from the Blood Indians in 1931 – he was the first non-native to be so recognized – and an lld from the University of Alberta the next year.

In retirement in Victoria, Walsh continued his keen interest in Alberta politics. He entered the debate raging over controversial legislation passed by the Social Credit government of William Aberhart*, an administration that viewed control of bank credit as essential to economic recovery from the Great Depression. In a letter published on the front page of the Edmonton Journal on 14 Sept. 1937, he maintained that the Credit of Alberta Regulation Act had been correctly disallowed by the federal government because it went beyond the province’s jurisdiction. It was banking legislation pure and simple, and not a question of property and civil rights as the province suggested. This foray from afar was his last public statement. After suffering a stroke and a heart attack, Walsh died in Victoria and was buried in Calgary’s Union Cemetery.

AO, RG 80-5-0-120, no.11079. GA, M 1278. Calgary Herald, 14, 18 Jan. 1938. Edmonton Journal, 25 April 1931. Cyclopædia of Canadian biog. (Rose and Charlesworth), vol.1. L. [A.] Knafla and Richard Klumpenhouwer, Lords of the western bench: a biographical history of the supreme and district courts of Alberta, 1876–1990 (Calgary, 1997). D. B. McDougall et al., Lieutenant-governors of the Northwest Territories and Alberta, 1876–1991 (Edmonton, 1991). Who’s who (London), 1936.

Cite This Article

Kenneth Munro, “WALSH, WILLIAM LEGH,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 23, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/walsh_william_legh_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/walsh_william_legh_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Kenneth Munro |

| Title of Article: | WALSH, WILLIAM LEGH |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2015 |

| Year of revision: | 2015 |

| Access Date: | December 23, 2025 |