Source: Link

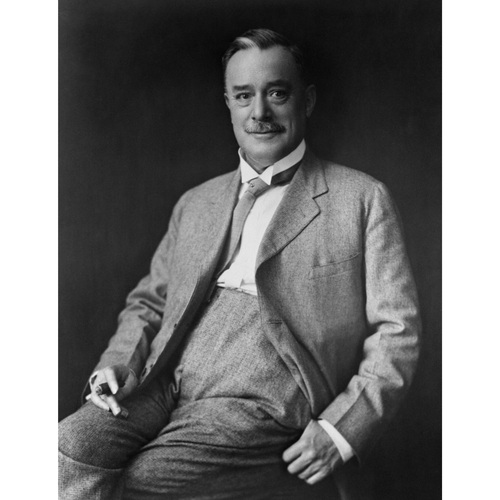

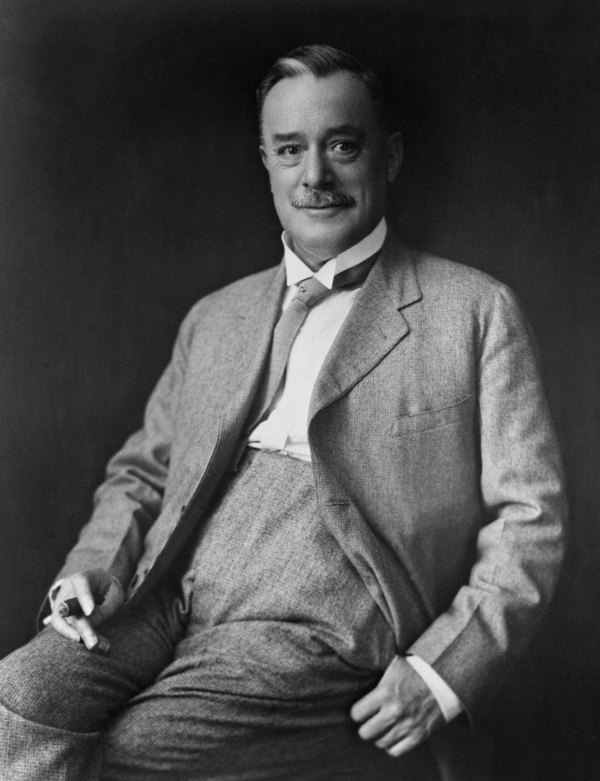

EDWARDS, ROBERT CHAMBERS, journalist and politician; b. 1859 or 1860, probably on 12 September, in Edinburgh, son of Alexander Mackenzie Edwards and Mary Chambers; m. 30 June 1917 Katherine Penman in Calgary; they had no children; d. there 14 Nov. 1922.

Bob Edwards’s father was a medical doctor in Edinburgh and his mother, according to his own testimony, was a member of the famous Scottish publishing family. Orphaned as a youth, the boy was raised by two maiden aunts. He was apparently educated at a private school in St Andrews and at the Royal High School, Edinburgh. Later he attended the University of Glasgow for three sessions, between 1877 and 1880, but did not graduate.

After he left school Edwards travelled to France where he briefly published an English-language newspaper, the Traveller (Boulogna). In 1884 he joined his brother Jack in emigrating to the United States. They first went to Wyoming; there they spent their summers on a ranch at Horseshoe Creek and the winters in Cheyenne. Three years later, Edwards and his brother bought a farm in Iowa but the next ten years of his life are a mystery, revealed only in part through hints in his writings. He mentions being in Chicago, St Paul, Minn., Kansas City, Arkansas, and San Francisco, adding “the only really useful knowledge we possess today has been obtained while knocking about the continent and the United States – broke.” In 1897 he arrived at Wetaskiwin (Alta), where he launched the Wetaskiwin Free Lance. It was a professional weekly of news, wit, and social comment, produced by a man of considerable journalistic talent and experience. Owning no presses, he had it printed by other newspapers. Within a short time, it was popular far beyond the Wetaskiwin area, but quickly lost its local support after Edwards made humorous comments about local merchants and they cancelled their advertising. Employed briefly by the Winnipeg Free Press in 1899, he soon discovered that he preferred to be his own boss. He returned to Alberta later in the year to publish the Alberta Sun at Leduc; he then moved the weekly to Strathcona, across the river from Edmonton. In 1901 he started the Wetaskiwin Breeze but the next year, when his friend Jerry Boyce opened a hotel in High River, Edwards decided to join him. On 4 March 1902 he published his first edition of the Eye Opener, thus named “because few people will resist taking it.”

Although it was the forerunner of the famous Calgary Eye Opener, the newspaper was still a small-town weekly which contained a mixture of local news and humour. It was well supported by local advertisers, but Edwards encountered considerable hostility from the clergy because of his excessive drinking and his frequent comments about liquor. During his two years at High River, he invented the character of Peter J. McGonigle, editor of the mythical Midnapore Gazette who spent much of his time at the bar of Nevermore House. McGonigle was a sage, a gentleman, and a drunk – not unlike Edwards himself. Edwards also invented Albert Buzzard-Cholomondeley, an English remittance man whose “letters” home contained ingenious and hilarious methods of extracting money from his father.

In the summer of 1903 Edwards ran foul of a Presbyterian minister in High River, calling him a “misfit man of God.” Shortly thereafter Edwards moved to Calgary, where the Eye Opener was soon established as a national newspaper of wit, satire, and political comment. By 1908 it had a circulation of 18,500 copies, with 4,000 being sold in Toronto, 2,600 in Winnipeg, 1,000 in Vancouver, and 1,800 on Canadian Pacific Railway trains.

Politically, Edwards leaned towards the Conservatives, but no party or individual was safe from his vitriolic attacks. When William Mackenzie and Donald Mann* (“Bill” and “Dan” in the Eye Opener) attempted to sell their share in the Winnipeg street railway system for $24 million, Edwards described their holdings as a pile of junk. On learning that Robert J. Stuart was a candidate for Calgary alderman, Edwards ridiculed him with the following comment: “We understand – ha ha! – that – haw haw! – R. J. Stuart – ah-yaw-haw – ha ha ha! – is going to run – oh oh ha ha – for alderman – ha ha ha ha ha ha! – Ha ha ha ha ha ha – ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha!” Edwards considered Sir Wilfrid Laurier*’s government to be corrupt, but at the same time he commented, “A propos Liberal and Conservative parties; of two evils it is best to choose neither.”

Because of his outspoken comments, Edwards gained the ill will of a number of politicians and businessmen. In 1905 he fended off a libel suit filed by John Stoughton Dennis and the CPR after he attacked the railway’s irrigation project east of Calgary. Richard Bedford Bennett*, as CPR solicitor, acted for the railway. Even though the case was dismissed, Edwards launched a bitter attack on Bennett, Dennis, and the CPR. He concentrated on unsafe railway crossings, particularly the ones at Calgary. In 1906 he began to publish photographs of train crashes, labelling each a CPR wreck. Then, on 7 April 1906, he featured a large portrait of Bennett and captioned it “Another C.P.R. wreck.” By 1911, however, Edwards had made a complete about-face and he became a supporter of Bennett, predicting that he might some day become prime minister of Canada. In the meantime, in 1908 the Eye Opener had accused Conservative leader Robert Laird Borden* of fathering an illegitimate child. Although no action was taken against Edwards in this instance, a court order was issued to prevent distribution of the newspaper in Borden’s home riding of Halifax.

Perhaps the most ludicrous legal case occurred in 1906, when Edwards carried a story about his mythical editor, Peter J. McGonigle, purportedly released from jail after serving time for horse theft. At a banquet tendered for McGonigle in Calgary, a telegram supposedly sent by Lord Strathcona [Donald A. Smith*] was read to the audience. It stated in part, “The name of Peter McGonigle will ever stand high in the roll of eminent confiscators. Once, long ago, I myself came near achieving distinction in this direction when I performed some dexterous financing with the Bank of Montreal’s funds. In consequence, however, of CPR stocks going up instead of down, I wound up in the House of Lords instead of Stony Mountain [penitentiary].” Strathcona was reportedly infuriated by the article and instructed his solicitors to take legal action. However, when the nature of the Eye Opener was explained by the solicitors’ Calgary agents, he was persuaded to abandon the suit.

Another of the Eye Opener’s opponents was Clifford Sifton, whom Edwards accused of having relations with a married woman in 1905, at the time of negotiations for the formation of the provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan. Three years later, Edwards heard a rumour that Sifton was backing the establishment of a Liberal newspaper in Calgary to counteract the influence of the Eye Opener. A short time after, Daniel McGillicuddy launched the Calgary Daily News and immediately prior to the election of 1908 he published a stinging personal attack on Edwards, calling him a “miserable wretch of a depraved existence,” a libeller, character thief, coward, liar, drunkard, drug addict, and degenerate. Edwards sued for criminal libel and won the case, but McGillicuddy was fined only $100.

Edwards never forgave those involved in the lawsuit. He ridiculed McGillicuddy’s lawyer, Edward Pease Davis, to such an extent that the man initiated a successful libel suit and Edwards was forced to publish an apology. Edwards also accused the judge, Nicholas Du Bois Dominic Beck, of political bias, describing him on one occasion as the “narrow, prejudiced, fanatical Beck.” As for McGillicuddy, Edwards was bitter even after the man was dead. When Edwards was elected to the Legislative Assembly of Alberta 13 years after the suit, he would write, “Isn’t it remarkable, here we are in the legislature and McGillicuddy is in hell?”

Believing that the McGillicuddy case signified a lack of support from Calgarians, Edwards tried to relocate his newspaper in Toronto or Montreal in 1909, but finally moved to Port Arthur (Thunder Bay), Ont., for a year, and then to Winnipeg for 1910 and early 1911. By April 1911, however, he was back in Calgary. During this time, he lost much of his vitriol and began to rely more on humour as a means of political condemnation. He started to sprinkle the pages of the Eye Opener with aphorisms such as “Politics is a good game, but a mighty poor business,” and with so-called “social notes” which poked fun at the elite. For example, in 1911 he wrote, “We learn that Miss Mary E. Frobisher, of Didsbury, is engaged to be married to the well-known Calgarian, Mr. John T. Billcoe, on Nov. 20. It is apparent that Titania was not the only woman who loved a donkey.” Many of his comments related to liquor, for although he tried to stop drinking on several occasions, he never overcame his alcoholism. “Every man has his favorite bird,” he wrote. “Ours is the bat.” In spite of, or perhaps because of, his drinking problem, he fully supported the introduction of Prohibition to Alberta in 1916. Yet, once the measure was implemented and he saw how drinking had moved from the bar room into the home, he became its outspoken critic.

Bob Edwards remained a bachelor until he was in his late fifties, living in hotel rooms and publishing his newspaper from a tiny office. Occasionally he had secretarial help but he always sent his copy to one of the local daily newspapers to print. In 1913 he met Katherine Penman, a 20-year-old woman just out from Scotland, who initially was in Bennett’s law office and then worked in the land titles building. They were married, both unattended, in 1917 but Kate stayed a closed part of her husband’s life, her name seldom being mentioned in his newspaper.

Because of Edwards’s reputation as a humorist, he was encouraged in 1920 to consolidate his writings in an anthology. Not satisfied with simply reprinting old material, he added new stories and jokes, often embellishing accounts published years before. The result was a 90-page pulp magazine entitled Bob Edwards’ Summer Annual, which was sold out in a few weeks. An agreement was then made with the Musson Book Company Limited of Toronto to publish the magazine each summer. In total, five annuals were produced, two appearing posthumously.

Over the years, many people had urged Edwards to stand for public office but he had always resisted the temptation; he preferred to take a neutral stand where party politics were concerned. However, in 1921 he finally succumbed, running as an independent and easily winning a seat in the Alberta legislature. Although he had neither advertised nor campaigned, he still polled the second largest vote in Calgary’s field of 20 candidates. He sat for one session and made only one speech, in which he condemned the effects of Prohibition. Already ill, he grew worse and passed away on 14 Nov. 1922.

Throughout his life, Bob Edwards used humour and satire to advocate social change. Sympathetic to the poor, he spoke out against political corruption, exposed swindlers and fraudulent real estate salesmen, and favoured law reform, relaxed divorce laws, and Canadian nationalism. In his time he was the best-known journalist in the Canadian west.

[The Calgary Eye Opener was published and edited by Bob Edwards until 29 July 1922, and was continued by his wife until at least 18 Aug. 1923. The paper was eventually sold to a Minneapolis firm, which continued the Eye Opener as a small humour magazine.

The principle sources for information on Edwards’s career are [J. W.] G. MacEwan, Eye Opener Bob: the story of Bob Edwards (Edmonton, 1957), and the two anthologies of his writings edited by Hugh A. Dempsey, The best of Bob Edwards (Edmonton, 1975) and The wit & wisdom of Bob Edwards (Edmonton, 1976). A six-part series on his life by Andrew William Snaddon appeared weekly in the Calgary Herald between 22 Sept. and 27 Oct. 1956.

There seems to be no body of papers on Edwards or the Eye Opener. A small collection, consisting of little more than a few random letters, exists in the GA, (M 353–56, M 2623, M 3826, M 3943). Edwards’s attendance at the Univ. of Glasgow is documented in the matriculation records in its Arch. and Business Records Centre. Information confirming his father’s medical career was obtained from the Royal College of Surgeons, Edinburgh, and the Royal College of Surgeons of England, London.

No complete file of the Eye Opener has survived. In 1962 the known extant copies were microfilmed by the Canadian Library Association; some additional issues have subsequently been obtained by the Glenbow Library, Calgary, and the Univ. of Alta Library, Edmonton. The Glenbow Library holds a complete set of Bob Edwards’ Summer Annual (Toronto). h.a.d.]

G. C. Porter, “Legendary Midnapore character made Calgary laugh; Lord Strathcona was not amused,” Calgary Herald, 4 Feb. 1939. Andrew Snaddon, “Bob Edwards’ story a bit of a mystery,” Calgary Herald, 4 Dec. 1954. Alberta newspapers, 1880–1982: an historical directory, comp. G. M. Strathern (Edmonton, 1988). Max Foran, “Bob Edwards & social reform,” Alberta Hist. (Calgary), 21 (1973), no.3: 13–17. Bertha Hart Segal, “‘Bob’ Edwards,” Cattlemen (Winnipeg), June 1950: 18, 35, 42. T. U. Primrose, “Bob Edwards of High River,” Cattlemen, January 1954: 6, 33.

Cite This Article

Hugh A. Dempsey, “EDWARDS, ROBERT CHAMBERS,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 20, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/edwards_robert_chambers_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/edwards_robert_chambers_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | Hugh A. Dempsey |

| Title of Article: | EDWARDS, ROBERT CHAMBERS |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2005 |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | December 20, 2025 |