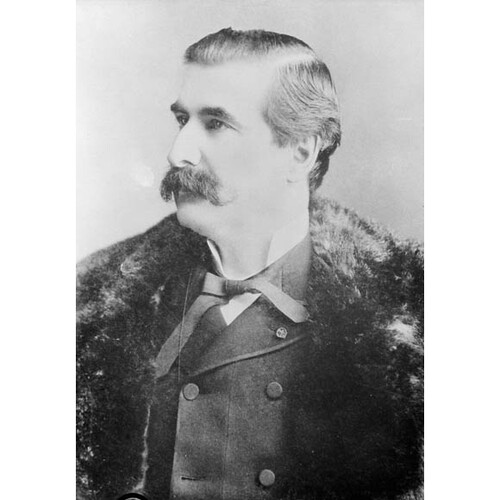

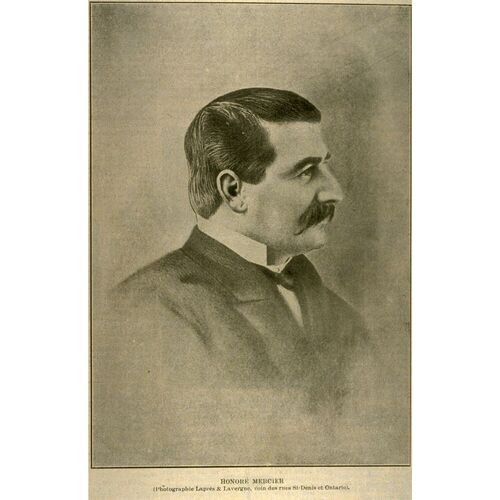

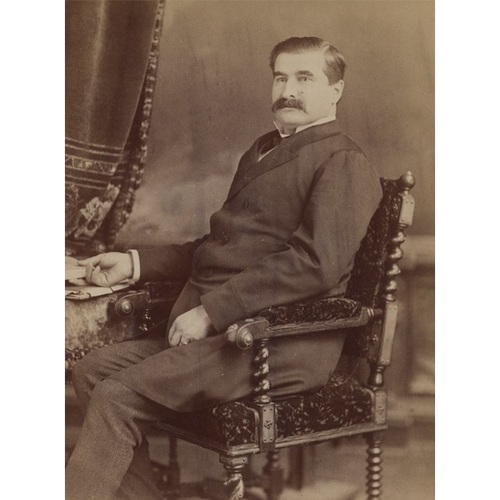

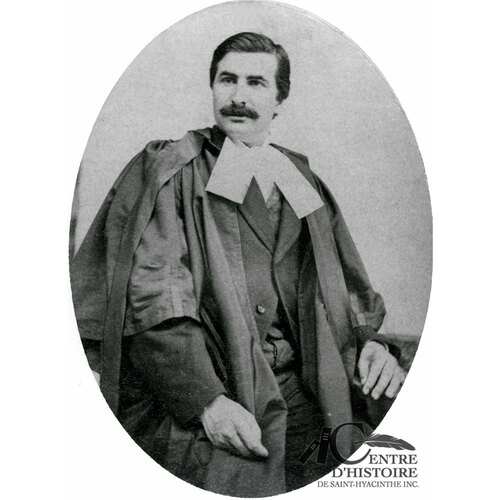

MERCIER, HONORÉ, journalist, lawyer, and politician; b. 15 Oct. 1840 in Saint-Athanase (lberville), Lower Canada, son of Jean-Baptiste Mercier, a farmer, and Marie-Catherine Timineur (Kemener); m. first 29 May 1866 Léopoldine Boivin in Saint-Hyacinthe; m. there secondly 9 May 1871 Virginie Saint-Denis; d. 30 Oct. 1894 in Montreal.

Honoré Mercier was a descendant of a family originally from Tourouvre in Le Perche, whose ancestor Julien Mercier had settled at Quebec in 1647. Father and son, the Merciers were farmers. Jean-Baptiste Mercier, a staunch supporter of Louis-Joseph Papineau*, was imprisoned for helping two Patriotes flee to the United States. His patriotic fervour did not subside with time and his house was a hotbed of liberalism frequented by Rouges of all shades. The young Honoré was raised in the ambiance of the events of 1837–38.

Mercier was enrolled on 23 Sept. 1854 at the Collège Sainte-Marie in Montreal, which provided the course of studies that was still being offered in European Jesuit colleges. Whether as day student or boarder, he maintained steady habits of work and was consistently among the best pupils. In May 1857 he was admitted into the Congrégation de la Très Sainte Vierge and the following year was made responsible for arranging recreational activities. He displayed such astonishing qualities as an organizer that in the fall of 1860 he assumed the leadership of a “militia” of some 30 boys. A classmate, writing in the college paper, described him as “pale,” with “piercing grey eyes,” “a graceful bearing,” and “attractive manners.” According to those close to him, he recruited people by his way of speaking and his moral integrity; he compelled recognition with his logical reasoning, energy, and lively mind; through his natural inclination to trust in true friends he attained his goals. Father Jean-Baptiste-Adolphe Larcher, who taught him in the first form (Latin elements) and later in the sixth form (Rhetoric) and with whom he formed a deep friendship, endeavoured to develop his oratorical gifts in the college’s Académie Française. He instilled in Mercier a profound attachment to the church, to France, and to Lower Canada as the mother province and protector of all French Canadians wherever they were in North America. Honour, unity, and loyalty were recurring themes in the young orator’s speeches.

Writing in his diary in the summer of 1861, Mercier pondered the choice of a career. Life seemed a vale of tears “for virtually its whole length.” He counted upon God to guide him in his choice, which would lie in “becoming committed to one of the essential things in life, working for the commonweal in this station in life or that, helping one’s compatriots in this employment or that.” He considered four professions: artist, lawyer, soldier, and priest. Although he seems to have been drawn more to the law, he did not manage to make a choice. Returning to the college in September, he remained in a state of nervous tension, swinging rapidly from hyperactivity to depression. His teachers thought that he was suffering from overwork. He took to his bed on 15 December, went home to rest for a while, and then on 10 Feb. 1862 withdrew from the college for good. His education had instilled in him a deep faith and dreams of greatness in the service of others, as well as good work habits and a horror of mediocrity. He left vowing a filial attachment to the Society of Jesus and to Father Larcher in particular.

At 21 years of age Mercier began articling in the law office of Maurice Laframboise* and Augustin-Cyrille Papineau in Saint-Hyacinthe, a small provincial town where the priests at the seminary and the seigneur, Louis-Antoine Dessaulles, were the poles of intellectual and political life. He boarded with two students, Louis Tellier and Paul de Cazes, and became friends with Abbé François Tétreau, an intellectual who was committed to the cause of French Canada and who had great influence on young people. His employers introduced him into liberal circles. He also fell in love with Léopoldine Boivin, whose guardian set as a condition for their marriage that Mercier secure permanent employment. In a hurry to succeed, caught up in the political restlessness that was stirring the local élites, consumed with ambition, he neglected his studies and in July 1862 agreed to succeed Raphaël-Ernest Fontaine as editor of Le Courrier de Saint-Hyacinthe, a newspaper with Liberal-Conservative leanings. Mercier, who never stayed out of any debate, displayed great independence of mind. During discussion of a militia bill of that year he proposed that retention of the colonial tie be made contingent on Great Britain’s willingness to contribute to the military defence of Canada. He denounced the principle of representation by population, claiming it “would lead to the death of French Canadian society.” He advocated a credit institution for farmers to stop emigration to the United States. Following Louis-Victor Sicotte*, the member of the Legislative Assembly for Saint-Hyacinthe, he endeavoured to reconcile national sentiment and liberal ideas.

In May 1863 the premier of the Province of Canada, John Sandfeld Macdonald*, forsook the principle of the double majority and replaced Sicotte with Antoine-Aimé Dorion as his lieutenant. Mercier refused to support Dorion’s Rouges, whose orientation he considered too anticlerical and insufficiently national, but he promised to judge the new cabinet by its actions. In the election of June and July 1863 the government, including George Brown* and the champions of “rep by pop,” was returned. Mercier was forced to draw one conclusion: the party spirit splitting French Canadians worked in favour of English Canada. He thus arrived at a strategy designed to bring liberals and conservatives into a patriotic formation that, leaving “past resentments and present jealousies” behind, would present a common front to the Rouges allied with the Grits. Le Journal de Québec reprinted Mercier’s proposal, endorsing it, and Mercier endeavoured to publicize it. He assailed the Rouges in Le Courrier; he confronted Laframboise, a candidate in a summer by-election, on the hustings; in public lectures he advanced traditional Christian propositions to counter Dessaulles’s philosophical Darwinism; and he condemned his former leader Sicotte for deserting the political arena in favour of a comfortable berth on the Superior Court. That autumn he campaigned for Rémi Raymond, brother of the vicar general of the diocese Joseph-Sabin*. Raymond was the candidate of the Séminaire de Saint-Hyacinthe and was running in a by-election against Augustin-Cyrille Papineau, a disciple of Dorion.

When the debate on Canadian confederation got underway in 1864, Mercier was a leading local figure, but also a man without a permanent situation. In order to assure his future and earn Léopoldine’s hand, he went to Montreal in the spring to continue his law studies, which he thought he could finance by making irregular contributions to Le Courrier. Its owners enjoined him to support the proposed confederation, which he regarded as a mechanism for crushing French Canadians, and he left the paper on 4 May. Then began a difficult period. Mercier worked like a demon, longed for his fiancée, and lived by his wits, especially by borrowing small sums right and left. He took François-Maximilien Bibaud*’s law course at the Collège Sainte-Marie and occasionally agreed to deliver a speech against confederation. On 3 April 1865 he was finally called to the bar.

Mercier established himself in Saint-Hyacinthe. There he was again with his fiancée, with Abbé Tétreau, with his friends Pierre Boucher* de La Bruère, Paul de Cazes, and Michel-Esdras Bernier. Life went on as before – still hectic. Mercier was caught up in his love, his law practice, the political fights, and the intellectual sparring. Following the example of the episcopate, he came around to accepting confederation. He was president of the Union Catholique of Saint-Hyacinthe, a study group that had a library and a reading-room where young and old faced one another in public debates. The Union Catholique was modelled on the Institut Canadien, except that it had a chaplain, Abbé Tétreau. In February 1866 Mercier and his three friends were on staff at Le Courrier de Saint-Hyacinthe, which was backing the team of George-Étienne Cartier* and John A. Macdonald. But Cartier’s desire to have the British government arbitrate the disagreement between the Maritime provinces and Canada in the confederation negotiations led Mercier to resign on 23 May. In his view, appealing to London perpetuated an antiquated colonial status and constituted a dangerous precedent for the autonomy of the future provinces.

Undoubtedly the party yoke weighed upon Mercier. He was more successful in his profession, for he was considered the best criminal lawyer in the region. This reputation, and probably the money that came with it, swayed Lépoldine’s guardian. Mercier was married on 29 May 1866 in the cathedral of Saint-Hyacinthe. The couple’s first child, Élisa, was born in 1867, but their family bliss was short-lived. Léopoldine, who had always been frail, died on 16 Sept. 1869. Mercier sought refuge in his work and kept himself busy in public life. He was one of those people who gave lectures and concerts in aid of wounded French soldiers and sang La Marseillaise in the streets when the German victory over France was announced. He found a certain consolation in de Cazes’s home. There he met Virginie Saint-Denis, who was his friend’s sister-in-law and 13 years younger than he. A romance began and Mercier was married again on 9 May 1871. He had gradually recovered his emotional stability, his joie de vivre, and his zest for a great political adventure.

The moment came late in 1871 when the Parti National was being set up by Louis-Amable Jetté* and Frédéric-Ligori Béïque*. In theory it was to bring together Conservatives and Liberals willing to “put the national interest” ahead of party interest. This was an idea dear to Mercier, who helped develop the platform, agreed to act as secretary, and was elected to the House of Commons for Rouville on 28 Aug. 1872, thanks to the backing of the curé of Saint-Césaire. A Mercier, fired with enthusiasm, moved to Ottawa, perhaps not sufficiently conscious of the real status of the Parti National, which had recruited few Conservatives, lacked an organization, and sat in the opposition with the Liberals under the leadership of Alexander Mackenzie and Antoine-Aimé Dorion; the party was merely an election stand-in for the Liberal party. That year John Costigan*’s motion for the disallowance of New Brunswick’s Common Schools Act of 1871 and for the legal establishment of publicly funded Catholic schools in that province provided the occasion for Mercier’s maiden speech. He argued that the rights of minorities should prevail over short-lived parliamentary majorities, warned the Protestant majority that it might one day find itself in the minority, rebuked Hector-Louis Langevin* for being spineless, and called for a sacred union of French Canadians and Catholics. This fiery speech, which was highlighted by an allusion to the independence of Canada, displeased Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald as much as it did the leaders of the opposition. Macdonald found a way out by persuading John Sweeny*, the Catholic bishop of Saint John, to let the school question be handed over to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council; the others warned Mercier to stick to the party line and respect party discipline. Mercier reacted to the warning with indignation. When the Macdonald government fell over the Pacific Scandal [see Sir John A. Macdonald; Sir Hugh Allan*], Mackenzie formed a government with no members of the Parti National, and in the 1874 elections the Liberal leaders let Mercier know that he was persona non grata in their party. Mercier did not insist and did not run for re-election.

Disappointed and fully aware that there was little room in politics for independent spirits, Mercier fell back on his law practice and concentrated his affections on his family. Children came: Iberville, born in 1872, did not survive but Héva was born on 7 June 1873, Honoré* on 20 March 1875, Paul-Émile on 16 March 1877, and Raoul-Joseph-Arnaud on 15 Dec. 1878, though he died in infancy. Mercier also took an interest in the development of Saint-Hyacinthe. In 1872 he invested in a factory making ribbon and braid, and in 1874 he helped found the Compagnie d’Aqueduc de Saint-Hyacinthe. But he could not forget politics and bided his time. Dorion’s departure to the bench in 1874, and the Liberal party’s development of more conciliatory positions towards the church led him back to politics within its ranks. Like a novice he had to prove himself and show some flexibility. In April 1876 he took the first step with a lecture before the Club National, which had been founded by Maurice Laframboise in 1875 to counterbalance the Club Cartier, where Joseph-Adolphe Chapleau shone. Then he put his oratorical talent at the service of the party. He supported Toussaint-Antoine-Rodolphe Laflamme, the lawyer for Joseph Guibord*’s widow, in the by-election in Jacques-Cartier on 28 Nov. 1876, and backed Wilfrid Laurier* in Drummond and Arthabaska and then in Quebec East in 1877. He aided the party cause in the provincial general election of 1 May 1878, which followed the dismissal from office of Charles Boucher* de Boucherville’s Conservative government by Lieutenant Governor Luc Letellier* de Saint-Just. Conservatives and Liberals were neck and neck on election night. A parliamentary majority for the government that Liberal leader Henri-Gustave Joly* was preparing to form would depend on a few votes, indeed on that of Arthur Turcotte*, the independent member for Trois-Rivières. Mercier thought himself entitled to the party’s gratitude and, doubtless with Laurier and Laflamme pulling strings for him, he ran in Saint-Hyacinthe in the federal general election on 17 Sept. 1878. He was narrowly beaten and earned the customary charivari and the black mourning crape hung above his door. His adversaries at Le Courrier thought they had finished him off. They forgot destiny.

On 3 Nov. 1878 Pierre Bachand*, member for Saint-Hyacinthe and provincial treasurer, died suddenly. He had been the linchpin in the Joly cabinet. The premier looked for a strong man, a popular speaker able to hold his own in the house and on the hustings against Chapleau, the rising star of the Conservative party and one of the great orators of his generation. Chapleau, who was often bombastic, favoured the rhythm of long, periodic sentences in his speeches. Mercier, closer to the people and more sensitive to national frustrations, used clear logic, connecting his arguments by short sentences full of facts and figures. Chapleau sought to please, Mercier to convince. It was evident that Joly had to choose Mercier and on 1 May 1879 he was appointed solicitor general. The following month, with the support of all the party’s leading performers, he was elected in Saint-Hyacinthe.

Mercier took his seat in a house caught in full crisis. As a backdrop there was Letellier de Saint-Just’s dismissal of Boucher de Boucherville, which had unexpectedly brought the Liberals to power. The Conservatives, who were in control of the Legislative Council, were seeking revenge for this “coup d’état.” They proceeded in three stages. Macdonald, who had been returned to power as prime minister in 1878, removed Letellier de Saint-Just from office and replaced him with a long-time Conservative, Théodore Robitaille, on 26 July 1879. In August the Legislative Council paralysed the government by refusing to vote supply. While the Liberals were organizing a popular campaign against the council, Chapleau was busy behind the scenes negotiating the defection of dissatisfied or ambitious Liberals, in order to create a strong administration. He won five of them over, and Joly thereupon lost his majority in the assembly. The lieutenant governor called upon Chapleau to form a government; Mercier then became just another member of the legislature and resumed his practice at Saint-Hyacinthe in partnership with Odilon Desmarais.

Hardly had the political crisis occasioned by Letellier de Saint-Just been resolved when another, more far-reaching one came to the surface. Both the Conservatives and the Liberals were outflanked, the former on their right and the latter on their left. Chapleau was unable to curb his party’s ultramontane wing, which was seeking the heads of his friends and advisers Louis-Adélard Senécal* and Arthur Dansereau*. On the Liberal side Joly anxiously watched Honoré Beaugrand* and Senator Joseph-Rosaire Thibaudeau launch La Patrie, a new hotbed of Rouge ideas, in Montreal in 1879. In fact ultramontanes and radicals wanted to dominate their respective parties. To escape being controlled by the extremes, the centre of each party contemplated a coalition with the other. They were in agreement on the fundamental questions: keeping the current social and political arrangements with the church, reforming the franchise, broadening the school system by introducing technical and professional instruction, and reorganizing the public service. All that separated them were questions of personality, individual antipathies, and party discipline. In February 1880, through an intermediary, Chapleau took the initiative of sounding out Mercier, the Liberals’ rising star. Mercier set as conditions the abolition of the Legislative Council and a fair distribution of cabinet portfolios. Word of the discussion was leaked, and the anger of ultramontanes and radicals put an end to negotiations. Chapleau concentrated on running the province, and through borrowing on the French market and the formation in 1880 of the Crédit Foncier Franco-Canadien he strengthened his hold on public opinion. Mercier pursued his dreams of coalition. He was edging past Joly in popularity within the party and with the public, and he was shaping the future. Twice in the spring of 1881, during a Liberal convention and at a banquet for Edward Blake*, he repudiated “all the ungodly, revolutionary or socialist doctrines which are unsettling the world.” He added: “Our enemies . . . have attributed principles to us that we do not profess, and they have reproached us for ideas that we have never expressed.” In secret, under the benevolent eye of curé François-Xavier-Antoine Labelle, Mercier and Chapleau undertook new negotiations, which foundered on fresh indiscretions.

Tired of it all and influenced by advice from Macdonald, who did not much favour coalitions, Chapleau changed his strategy. At the height of his popularity, he called a general election in the autumn of 1881, made a sweep of the Liberals, settled the thorny problem of the Quebec, Montreal, Ottawa and Occidental Railway to the satisfaction of his friend Senécal, and then put his influence at Macdonald’s service in the federal election of 20 June 1882. In July he laid his cards on the table: Joseph-Alfred Mousseau*, secretary of state in the Macdonald government, became premier of the province and Chapleau went off to Ottawa to take over Mousseau’s office in the hope of supplanting Langevin, running Quebec through an intermediary, and making the ultramontanes fall into line. These grand manœuvres disconcerted the Liberals. Early in 1881 Mercier had moved his family to Montreal and gone into partnership with lawyers Cléophas Beausoleil* and Paul Martineau, fully determined not to run in the next election and to make his living solely through practising law.

But events again outran the control of those who were involved in them. The ultramontanes were not taken in by Chapleau’s scheming and they kept up their opposition to Mousseau. Friends and voters persuaded Mercier to remain in the fight. Once again Mercier was negotiating, this time with Mousseau, and once more he was being thwarted by the extremists in both parties. Damaged by these dealings undertaken without his knowledge, somewhat disillusioned, and doubtless weary, Joly resigned as leader of the party and on 18 Jan. 1883 designated his successor: Honoré Mercier. At the opening of the session Mercier stated his position on two fundamental questions in order to reassure both the Catholic Church and the people. First, in the educational field, the Liberal party intended “to ensure a practical and Christian education for [the] children.” “And to obtain this result,” added Mercier, “let us not be afraid to accept respectfully, but without abdicating our rights, the wise and prudent advice of the Council of Public Instruction.” Secondly, confronted with Quebec’s budgetary deficit, he proposed that, instead of a provincial resort to direct taxation as a means of restoring public finances, the federal government raise its annual grant, as fair compensation for the customs and excise duties handed over by the provinces at confederation. Outside the house he made open war on La Patrie. These goodwill gestures reassured the ultramontanes, who were still being kept out of the government by Mousseau. Mercier saw in their reaction signs of a new era. His pragmatism and appetite for power now led him to seek common ground with the ultramontanes. In July 1883 he had founded a newspaper in Montreal, Le Temps, to dissociate himself clearly from the radicals. That month, at a political rally in the riding of Saint-Laurent, he and Senator François-Xavier-Anselme Trudel*, the ultramontane leader, had criticized the old triumvirate of Chapleau, Senécal, and Dansereau. Mercier’s rapprochement with the ultramontanes, when the moderate Conservatives were still trying to reach an understanding with him, had the potential to change the political playing field. In Ottawa, Langevin, who was pulling the strings, took things in hand. Mousseau resigned on 10 Jan. 1884. John Jones Ross*, an old hand at politics whose position on ultramontanism was not sharply defined, formed a government in which the pivot turned out to be the ultramontane Louis-Olivier Taillon*. Mercier’s strategy had simply forced the Conservatives to reforge party unity.

Mercier now had to achieve a similar feat. The bitter struggle that Oliver Mowat*, the premier of Ontario, was engaged in with the federal government over provincial rights suggested a theme calculated to rebuild party unity. Mercier interpreted it for Quebec tastes: the federal conspiracy against provincial autonomy. Macdonald was a centralizer; his ministers Chapleau and Langevin were running Quebec through intermediaries; the central government was taking revenue from Quebec and blithely redistributing it among the other provinces. The constitutional theory formulated by judge Thomas-Jean-Jacques Loranger* gave Mercier the legal foundation on which to base a claim of provincial autonomy: the Canadian confederation is a pact between the provinces, which retain real sovereignty. This proposition coincided with the tradition of the Rouges, who had fought for provincial autonomy in 1865 and whom Mercier now endeavoured to restore to public favour. On 10 Dec. 1884, in a lecture on Charles Laberge*, he bluntly asserted that “there are no ungodly people or atheists in the ranks of the Liberal party; there may be a few men whom the unfair fighting and the deliberate calumnies of the politico-religious school [read: the ultramontanes] have driven to indifference but they are singular exceptions.” Some time later he backed Honoré Beaugrand of La Patrie as a candidate for the mayoralty in Montreal. The unity of the Liberal party seemed to have been sealed.

This unity rested, however, upon bases that existed because of special circumstances. Mercier was tolerating rather than accepting the radicals, whose anticlericalism ran counter to his deep-seated convictions and blocked his road to power in a province where the Catholic Church had great influence among the voters. The Métis uprising in the spring of 1885 [see Louis Riel*] showed how fragile these bases were. Public opinion in French Canada condemned the rebellion, but French Canadians saw reasons that made it excusable. Riel had alienated the Catholic episcopate with his messianic dream, but he retained the sympathies of the mass of French Canadians because of the ties of blood and culture. His surrender in May, his trial in July, and his death sentence on 1 August caused a turmoil intensified by the acquittal of two of his associates, William Henry Jackson* and Thomas Scott, who had been charged with treason-felony. Committees were formed, public meetings held, and petitions sent to the French-speaking ministers in Macdonald’s cabinet. This activity, designed to get Governor General Lord Lansdowne [Petty-Fitzmaurice*] to reprieve Riel on cabinet recommendation, rekindled the bitter struggle between Catholics and Protestants, French and English Canadians. Fearing that if the debate became too political it might harm Riel, Mercier stayed officially in the background in the tumult. In confidence he begged Chapleau to resign if Riel was not reprieved and to come and lead the movement on his behalf: “I shall be at your side to help you with my feeble efforts and to bless your name along with our brother Riel, spared the gallows.” Rather than risk a civil war, Chapleau remained in office.

Riel was hanged on 16 November. In Quebec, flags were flown at half mast and the patriots wore mourning bands. Bleus and Rouges came together spontaneously in a political movement aimed at bringing down the Macdonald government. On 22 Nov. 1885, before a crowd on the Champ-de-Mars in Montreal, Trudel proclaimed, “The nation’s duty compels us to break alliances of more than 20 years duration, to condemn leaders whom we have been proud to follow.” Mercier pleaded for the union of all true patriots to “punish those who are guilty,” and clearly sought to transform this movement into a national party. By mid December the movement was losing momentum with the rigours of winter, the disapproval of the clergy, and the warnings of journalist Joseph-Israël Tarte*, but Mercier and Trudel kept the agitation going. In January 1886 the National Conservatives – those breaking with the Conservative party over the Riel affair – founded their own newspaper, La Justice, in Quebec City. In the Legislative Assembly, Mercier was still evoking blood brotherhood, the call of the race, the example of the Patriotes, and the historic obligation for the province of Quebec to federate and protect the French minorities throughout North America. In June he launched a manifesto in anticipation of the forthcoming provincial election. It was an appeal for the union of all patriots to strengthen the position of Quebec within confederation. In it Mercier again took up the ideology developed by the élite among the rural clergy, but he remained open to the new realities emerging with industrialization and urbanization. The main planks of his platform were these: asserting the provinces’ autonomy; decentralizing the provincial government; retaining a denominational school system which would be broadened to include technical and professional instruction; guaranteeing minority rights; putting public finances on a sound footing; amending legislation on crown lands in a way favourable to settlers; improving the regulation of working hours; and reforming the legal system. The Liberals, the National Conservatives, and the ultramontanes, except for those in the diocese of Trois-Rivières, rallied to Mercier. The campaign lasted more than three months. Mercier conducted it at a furious pace, holding some 100 meetings. When the votes were counted Liberals and Conservatives were tied and the five National Conservatives who had joined Mercier held the balance of power. Cherishing the hope that they could be won over, Premier Ross, and then his replacement, Taillon, vainly clung to power. On 27 Jan. 1887 Taillon was defeated on the vote for speaker of the assembly and on 29 January Mercier was sworn in as premier. The coalition government had eight ministers, including two National Conservatives, Pierre Garneau* and Georges Duhamel.

When Mercier opened the session on 16 March, he had two priorities in mind: consolidating the bases of the Parti National, which was still only a coalition of ill-fitting, disparate elements, and then implementing the program he had set out. Consolidating the party was a matter for the medium term. For the time being, Mercier proceeded with the customary dismissals and appointments, and carried on negotiations to reinforce his parliamentary majority. As well, no doubt mindful of the Parti National’s misadventure in 1872, he entrusted organizing and financing the party to Ernest Pacaud* and Cléophas Beausoleil. In the medium term he hoped, through his speeches and charisma, to rally the mass of voters to his banner, and thus make himself independent of the ultramontanes, the radicals, and the National Conservatives. From this aim arose certain fundamental characteristics of his administration. It was marked by a personal, authoritarian style of leadership and, to cement unity, was punctuated with speeches to the public, attention-getting actions, and warnings against outside enemies. Mercier had an innate sense of publicity, and he was the first Canadian political leader to make systematic use of the nascent popular press to win the masses to his cause. Born of patriotic sentiment, the coalition would live by expressing it.

Another trait of Mercier’s government was the impetus he gave to the administrative machinery. He was a man who by temperament worked unremittingly and with unusual efficiency to get things done. On 16 March 1887 the speech from the throne announced a series of measures that included a complete review of the province’s finances and the holding of an interprovincial conference. The first bill brought forward by Mercier dealt with the incorporation of the Society of Jesus, which George III had slated for extinction right after the Treaty of Paris in 1763 by forbidding it to recruit new members. In Mercier’s view his was an act of justice, a gesture of personal gratitude, and a way to win the loyalty of the Montreal ultramontanes, who wanted the Jesuits to establish a university in that city. Civil recognition, a step that would allow the Jesuits to open educational establishments anywhere in the province, split the Catholic hierarchy. Cardinal Elzéar-Alexandre Taschereau feared for the monopoly held by the Université Laval. A compromise was reached in the committee for private members’ bills: the Jesuits could open teaching institutions in the dioceses of Montreal, Ottawa, and Trois-Rivières, but elsewhere they would have to obtain the diocesan bishop’s assent. This success prompted Mercier to look into the matter of the Jesuit estates. By virtue of the right of escheat the government had laid hands on the properties belonging to the Society of Jesus – seigneuries, urban lots, buildings – when the last Jesuit had died in 1800. In 1831 it had entrusted them to the House of Assembly to finance higher education. But since the 1850s the Jesuits, who had returned to Canada in 1842 [see Jean-Pierre Chazelle*] and now were backed by the ultramontanes, had been demanding compensation as despoiled owners [see Antoine-Nicolas Braun*]. Taschereau, on the basis of canon law, urged that this compensation be paid to the Catholic Church as a whole. The Protestants declared that the 1831 law had also given them rights to these assets. Mercier thought that he had sufficient strength to settle the question, which was poisoning the political climate, dividing Catholics, and holding up urban development. He took it upon himself to short-circuit the episcopate, negotiate behind the scenes directly with the Jesuits and the Vatican, and bring in a bill allocating $60,000 to the Protestant schools and a compensation of $400,000 which it would be up to the pope to redistribute as he pleased within the Catholic Church in Quebec. Mercier insisted on papal ratification of the arrangement in order to avoid any future dispute among Catholics on the matter. The Jesuits’ Estates Act was passed in July 1888. In January 1889 Leo XIII divided the sum, awarding $160,000 to the Jesuits, $100,000 to the Université Laval, $40,000 to the Montreal branch of the Université Laval, $20,000 to the prefecture apostolic of the Gulf of St Lawrence, and $10,000 to each diocese.

The ultramontanes were pleased that the question of the Jesuit estates was in the process of being settled, and the interprovincial conference held at Quebec from 20 to 28 Oct. 1887 shed lustre on the Mercier régime. All the provinces were represented at the meeting except British Columbia and Prince Edward Island, which had not dared displease Prime Minister Macdonald. In all, 20 ministers, including 5 premiers, took part in the discussions. Oliver Mowat, the premier of Ontario, chaired the deliberations. Mercier had prepared the agenda: 22 subjects that directly or indirectly concerned provincial autonomy. The delegates agreed upon 26 resolutions, which included protests against the federal government’s right to disallow provincial laws, against life appointments for senators, and against the continued existence of a legislative council in Quebec and Manitoba. Calls were made for an increase in federal subsidies to the provinces, recognition of provincial jurisdiction over matters not specifically mentioned in the constitution, increased powers for lieutenant governors, appointment by the provinces of a certain number of senators, and trade reciprocity with the United States. Macdonald gave a cold reception to Mowat, who went to Ottawa to provide him with an account of this memorable meeting. The prime minister did not act on the resolutions, but, perhaps unknowingly, Mercier had forged a mechanism that in the end would bring the provincial premiers into the running of the country. Mowat later paid him homage: “He was head and shoulders above every one of us.”

Mercier had more difficulty with the $3,500,000 loan that he had been authorized by the legislature to negotiate in order to stabilize public finances. He met with a refusal on the market in New York, where Canadian government emissaries did not give him a good press. Through dependable people, he secretly set negotiations with the Crédit Lyonnais in motion, and in January 1888 he went to Paris to settle arrangements. He then moved on to Rome to discuss the Jesuit estates.

Mercier was back in Montreal on 16 March 1888, and on 10 April he reported on his first year of government: construction of the Quebec and Lake St John Railway had been completed, commissions appointed to inquire into agriculture and into insane asylums, the Central Board of Health created, and an immigration office opened in Montreal. He seized the occasion to denounce imperial federation that would condemn the province “to compulsory taxation in blood and money and would drag [her] sons away to cast them into distant and bloody wars.” Returning to Quebec, he shuffled his cabinet. He kept the Department of Agriculture and Colonization for himself and gave the curé Labelle, who would have the rank of assistant commissioner, the task of organizing it. By order-in-council on 9 May, he appointed the province’s first three factory inspectors, but it was only on 19 June that he instituted factory regulations, putting into effect an 1885 law on child labour and sanitary conditions in factories.

The second session, which opened on 15 May 1888, was centred on economic development. Mercier’s government founded night schools for workers, continued subsidizing railways, and made a start on modernizing the road network to support the expansion of settlement and of the dairy industry. He secured passage of a new law on forests that eliminated a lumbering reserve created in 1883, prohibited the granting of timber limits in inhabited areas, and made settlers life-tenants of their land with the right to cut and sell wood on payment of a fee to the state. He released funds allocated for preliminary studies on the proposed construction of the Quebec bridge. Late in June, arguing that the province of Quebec had “the rights and duties” of a motherland, he named Laurent-Olivier David* and Narcisse-Henri-Édouard Faucher de Saint-Maurice as delegates to the seventeenth convention of French Canadians held at Nashua, N.H. This session of the legislature bore the stamp of hard work, but also of good fortune and grandeur. There were two failures, however: the Bank of Montreal vetoed his plan to convert the debt, and the Legislative Council rejected a bill limiting to one-quarter of a workman’s salary the amount subject to garnishee by a creditor.

The third session, which opened on 9 Jan. 1889, continued with reforms already initiated. But Mercier postponed settling the administration of asylums, in which state control of medical care was at stake. And he had to put up with Macdonald’s slowness in fixing the northern boundary of Quebec: Mercier located it on the south bank of the Rivière Eastmain, but Macdonald preferred the 52nd parallel.

Mercier was in top form. He fascinated people. His supporters showered him with praise and his friends flattered his vanity. In Montreal he lived in a magnificent stone residence on Rue Sainte-Pierre where Louis-Honoré Fréchette*, Laurent-Olivier David, Félix-Gabriel Marchand, Lomer Gouin*, and the élite of the Liberal party were frequent visitors. At Sainte-Anne-de-La-Pérade he had bought the rebuilt manor-house of the seigneur, Pierre-Thomas Tarieu de La Pérade. He renamed it Tourouvre and set up a stud-farm. He had reduced the parliamentary opposition to fewer than 15 and, through various manoeuvres, strengthened his position in the Legislative Council and on the Council of Public Instruction. He became authoritarian, abrupt. In 1889 he had Pierre Boucher de La Bruère stripped of his office as speaker of the Legislative Council and he crushed Alphonse Desjardins*, editor of the Legislative Assembly’s debates, who refused to alter the text of a speech he had delivered. Yet there were still tensions within the coalition. The radicals at La Patrie sneered at Mercier’s conservatism. Some young Quebec Liberals, who had formed a group around L’Union libérale, a newspaper founded in 1888, wanted to break with the National Conservatives. The ultramontanes were furious at Ernest Pacaud’s influence peddling, and were alarmed by the growing rumours of scandals.

These tensions were normal, and Mercier brought them under control. Relations with the federal government and with Protestant anglophone groups looked to be more serious. Macdonald had not forgiven Mercier for holding an interprovincial conference. The proposed debt conversion had displeased the English-speaking financiers in Montreal. The influence peddling aroused the scorn of puritans. Evangelical societies, upset by the French Canadians’ push into the Eastern Townships and eastern and northern Ontario as well as by the ambition of people like the curé Labelle to resettle Franco-Americans in the Canadian west, considered Leo XIII’s arbitration on the Jesuit estates another unprovoked attack by the Roman Catholics. Openly Catholic, French, and French Canadian, Mercier worried the English-speaking minority in the province. By the summer of 1888 the press in the Eastern Townships had shown signs of apprehension and indicated it disagreed with the lines along which the Jesuit estates’ question had been settled. In the autumn the Evangelical Alliance and the Protestant Ministerial Association of Montreal called for disallowance of the act. In March 1889 the refusal of the House of Commons to vote disallowance caused deep unrest in Ontario, which resulted in the creation of the Equal Rights Association [see D’Alton McCarthy]. Once more Canadian identity was at the heart of the controversy, and Mercier at the centre of a political storm. In public he took a firm stand. On 24 June 1889, Saint-Jean-Baptiste Day, he made known his position: “The province of Quebec is Catholic and French, and it will remain Catholic and French. While affirming our respect and friendship for the representatives of the other races or the other religions, while declaring our readiness to give them their rightful share in everything and everywhere . . . we solemnly declare that we will never renounce the rights that are guaranteed us by treaties, by the law and the constitution. . . . Let our rallying cry in the future be these words that will be our strength: Let us cease our fratricidal fighting, let us unite!” Behind the scenes Mercier kept his word. He negotiated with the Protestant committee of the Council of Public Instruction and instituted a policy of appeasement. Early in 1890 he had the Jesuits’ Estates Act amended and lent his support to a bill dear to the hearts of Protestants which recognized the ba degree as sufficient for admission to study for the learned professions (the law, notarial practice, and medicine). By springtime the storm was subsiding. The Equal Rights Association was isolated. Mercier had regained the trust of Protestant voters and Montreal financial circles. He had the support of the Grand Trunk. Circumstances were favourable for going to the people.

On 17 June 1890 Mercier, who had run in the Gaspé riding of Bonaventure, won a resounding electoral victory. In Ottawa, meanwhile, Joseph-Israël Tarte had begun to reveal the McGreevy scandal [see Thomas McGreevy], which put Langevin and the Macdonald cabinet in difficulty. On 4 Nov. 1890 the speech from the throne gave notice of a busy session for the assembly. Mercier opted for medical supervision of the insane by doctors employed and paid by the state, a decision that displeased the ultramontanes and that would later be a significant factor in his defeat at the polls. With the backing of the authorities in Rome once more, he secured passage of a bill uniting the Montreal School of Medicine and Surgery with the faculty of medicine of the Montreal branch of the Université Laval. In January 1891 he had the charter for the Baie des Chaleurs Railway Company, of which Senator Théodore Robitaille was president and Charles Newhouse Armstrong the contractor, rescinded. Mercier claimed that by failing to fulfil the terms of its charter the company was unduly delaying development of the Gaspé and wasting public funds. In February he put his prestige and campaign organization at Laurier’s service in the federal election. Macdonald won that contest, but for the first time the Liberals in Quebec emerged with an 11-seat majority. Then Mercier sailed for France, where he spent more than three months. Representing himself as the head of a French and Catholic province, he made a triumphal tour in France, Belgium, and Rome. But the Canadian government sabotaged his plan for borrowing $10,000,000 – he obtained only $4,000,000.

When he returned on 18 July 1891, Mercier found a country in turmoil. Macdonald was dead. It looked as though Tarte, who had laid 63 charges against Langevin, McGreevy, and the Department of Public Works, was going to bring down the new cabinet of John Joseph Caldwell Abbott. There were more and more rumblings of corruption in Mercier’s entourage. On 21 August the Senate railway committee made these rumours explicit. In Mercier’s absence, Pacaud had had $175,000 paid to Armstrong, the contractor, for work on the Baie des Chaleurs Railway. Armstrong had handed $100,000 back to Pacaud. “It’s the beginning of the end,” observed La Vérité of Quebec. And it was indeed the end. Mercier stood alone before a powerful Conservative machine. It had supporters in key positions in the administrative and judicial system, and it was eager to see the McGreevy scandal eclipsed and above all to overthrow the man who had removed Quebec from its hold. He faced the belligerence of people he had pushed around – for example, Philippe Landry*, the owner of the Beauport asylum, who was a major contributor to Conservative party funds. He was also confronted with the distrust of a Catholic episcopate that disliked his negotiating directly with the Vatican and filling the Legislative Council and the Council of Public Instruction with his creatures.

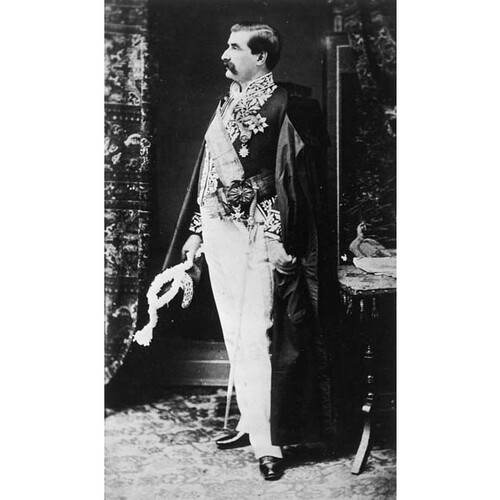

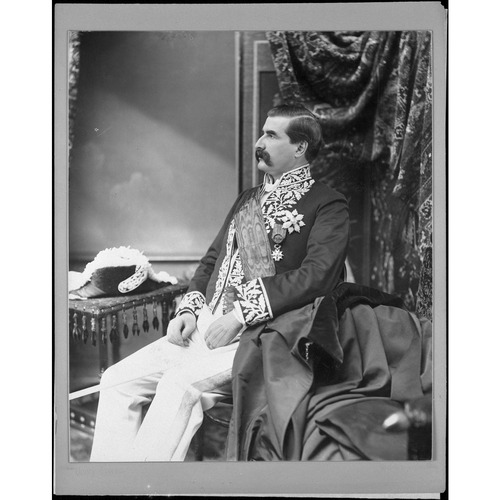

Mercier did not know what plots were being laid against him. He was slow to defend himself and did so badly before Lieutenant Governor Auguste-Réal Angers*. On 7 September Angers revealed his intentions. He restricted the government to dealing with urgent administrative matters, and then on 18 September forced Mercier to set up a royal commission. But on 16 December he dismissed him as premier, before the commission’s final report was in. He at once called on Charles Boucher de Boucherville to form a government, even though Boucherville did not have a parliamentary majority. At that moment the die was cast. While the chairman of the royal commission was writing its report, the Conservatives called an election. They also established another commission to inquire into Mercier’s administration and publish incriminating testimony day by day. On 8 March 1892, after a dirty and unusually vicious campaign, the Conservatives took 52 seats and Mercier’s people 18, with one independent being elected as well. When the chairman’s report was made public, it stated clearly “There is no evidence that any minister knew of [the Pacaud–Armstrong] agreement.” Then everyone went for Mercier. On 20 April the attorney general, Thomas Chase-Casgrain*, dragged Mercier before the courts on a charge of having defrauded the public treasury of $60,000 in the award of a contract to bookseller Joseph-Alfred Langlais. In October, Mercier, a commander of the Legion of Honour and the Order of Leopold, knight grand cross of the Order of St Gregory the Great, count palatine, appeared before the criminal court at Quebec. He was acquitted. The unrelenting harassment by his adversaries brought him renewed sympathy, and when he returned to Montreal he was carried in triumph from the station to his residence.

Once again Mercier was acclaimed, but he was ruined financially and physically. On 7 June he assigned his assets to two trustees. He had resumed practising law with a pair of young lawyers, Rodolphe Lemieux* and Lomer Gouin; in reality they were supporting him. Late in September he declared bankruptcy. The sale of his assets netted $20,660, but he owed $83,163. The diabetes that sapped his strength was dimming the sparkle of his eyes and wasting his features. He went to spend the winter in Europe, probably seeking treatment, and resumed his seat in the assembly on 3 Feb. 1893. Thenceforth Félix-Gabriel Marchand led the Liberal party. Mercier found new energy and seemed to envisage a return to power. He looked for a cause, and once more the Canadian west, where the Manitoba school battle was raging, supplied him with one. The Judicial Committee of the Privy Council, which had just issued an opinion rejecting a Supreme Court judgement that had been in favour of the Catholics, put him back in the saddle. On 4 April he delivered a lecture in Parc Sohmer before 6,000 people who had come to hear various speeches on Canada’s future. He presented an argument for emancipation from colonial status and evoked the evolution of “a great people recognized and respected among free nations.” His success on that occasion and a combination of circumstances led him to elaborate his idea and strategy: to create a mass movement which with the material and moral aid of the United States and France would see Canada attain the rank of an independent republic. Mercier was off on a crusade. In July he made the rounds of the Franco-American centres. At Providence, R.I., he advocated a broad alliance, with headquarters in Paris, to safeguard all peoples of French extraction. Elsewhere he preached the idea of a Canadian republic which, if the people so desired, might well annex itself to the United States.

This crusade involved Mercier in new controversies. Not without reason he was suspected of dreaming of an independent French Canadian republic. All the time his health was deteriorating. Early in August he left his law office to take to his bed. A fortnight later he was moved to Notre-Dame Hospital, where he died on 30 Oct. 1894. A crowd of more than 70,000 accompanied his coffin to his last resting place.

The life of Mercier – to some a victim and martyr, to others a wasteful leader who misappropriated public funds – was the stuff of which heroes are made. He was no sooner dead than the popular memory, nurtured by ideologues, politicians, and historians, began to draw a portrait of him that gave meaning to their time. It became the custom for a pilgrimage to be made to his grave on All Saints’ Day; 25,000 people went there to meditate in 1898. As his adversaries passed away and resentments subsided, his stature increased. The Liberals, believing in compulsory education, called to mind “Mercier’s schools,” and supporters of a second transcontinental railway recalled his patriotic vision and Labelle’s. In 1901, on Saint-Jean-Baptiste Day, Joseph-Israël Tarte raised Mercier to the rank of a national figure. Henri Bourassa* evoked the national coalition to fight Lomer Gouin, the premier, who was Mercier’s son-in-law. On 25 June 1912, when a monument to Mercier was unveiled in the legislative gardens at Quebec, the main lines of the legend were set: “And you who pass by this bronze statue, salute it, it is the soul of the native land, it is Mercier.” This festival of patriotism was both Mercier’s rehabilitation, a gesture restoring lost rights to public esteem, and his apotheosis. Mercier, having passed the test of history’s impartiality and of the people’s infallibility, became worthy of embodying French Canadian patriotism, of which he had been the living example. Far from seeking to describe Mercier as he had been, orators clothed him in present truth: it was patriotism that would enable the French Canadian race to survive and increase. The watchword “Let us cease our fratricidal fighting, let us unite!” acquired a ritual quality fit for exorcising future dangers.

Until the 1940s the collective memory constantly exalted this example. Mercier was evoked at all patriotic celebrations. The fortieth anniversary of his death was commemorated by a mass at Le Gesù in Montreal and a pilgrimage to his grave. The centenary of his birth was marked by a program on Radio-Canada, the publication of writings about his accomplishments and deeds, and biographies in the press. At the founding of the Union Nationale in 1935 and the Bloc Populaire Canadien in 1942, at the conscription crisis in 1944 and the adoption of the Quebec flag in 1948, the “great Mercier” was always present, inspiring, exhorting, exorcising, applauding. But he had been clericalized. His respect for the church and love of humanity were emphasized. The settlement of the Jesuits’ estates question was his greatest measure, and his agricultural and colonization policy his greatest work. With the acculturation of Franco-Americans, the rout of French-speaking minorities in western Canada, and the long depression of the 1930s, horizons had shrunk for French-speaking Quebeckers. The Mercier of the 1910s was the bearer of a messianic vision thrusting Quebec to the fore within the Canadian confederation and French Canadians to the fore in North America. He pointed to the future. Like the Samuel de Champlain* and Jos Montferrand [Joseph Montferrand*, dit Favre] dear to the ecclesiastical élites, the Mercier who overcame a crisis was a tiller who cultivated the soil of the past. He urged a withdrawal into one’s self to safeguard the Catholic and the French fact. “Let us cease our fratricidal fighting” meant “preserve what we have become,” and no longer “strive for what we might be.”

The myth of Honoré Mercier burst and disintegrated in the 1960s. Only a few separatists have since evoked his memory on occasion and projected their dreams through him. “But his dream of a free French state persists,” Marcel Chaput insisted in 1977. At the time of the Quiet Revolution historians sketched three portraits of the man: Mercier the patriot, who still embodied the soul of an entire nation; Mercier the nationalist, now Conservative or Liberal, now federalist or separatist, who no longer represented the aspirations of any but a fraction of the people; and Mercier the petit bourgeois whose “politics of grandeur” “concealed the class struggle and the uncurbed development of capitalism.”

The birth, marriage, and burial records of Honoré Mercier are at ANQ-M, CE4-3, 16 oct. 1840; CE2-1, 29 mai 1866, 9 mai 1871; CE1-51, 2 nov. 1894.

Pierre Dufour provides a bibliography of studies on Mercier in “L’administration Mercier, 1887–1891: anatomie d’une légende”

Revisions based on:

Bibliothèque et Arch. Nationales du Québec, Centre d’arch. de Montréal, CE601-S51, 10 mai 1881; CE602-S1, 18 mars 1877, 15 déc. 1878; CE602-S5, 20 sept. 1869.

Cite This Article

Pierre Dufour and Jean Hamelin, “MERCIER, HONORÉ (1840-94),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 2, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mercier_honore_12E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mercier_honore_12E.html |

| Author of Article: | Pierre Dufour and Jean Hamelin |

| Title of Article: | MERCIER, HONORÉ (1840-94) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1990 |

| Year of revision: | 2021 |

| Access Date: | April 2, 2025 |

![Hon. Honoré Mercier, Q. C. [image fixe] Original title: Hon. Honoré Mercier, Q. C. [image fixe]](/bioimages/w600.749.jpg)