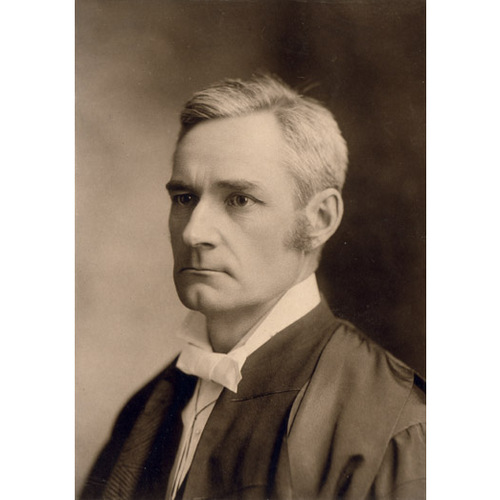

![Photograph of Edward Douglas Armour (1851-1922), a member of the Osgoode Hall Law School faculty.

Date: [ca. 1900]

Photographer: Lyonde

Reference code: P960.3

Source: Archives of the Law Society of Upper Canada. Original title: Photograph of Edward Douglas Armour (1851-1922), a member of the Osgoode Hall Law School faculty.

Date: [ca. 1900]

Photographer: Lyonde

Reference code: P960.3

Source: Archives of the Law Society of Upper Canada.](/bioimages/w600.14016.jpg)

Source: Link

ARMOUR, EDWARD DOUGLAS, lawyer, educator, journalist, and poet; b. 26 May 1851 in Port Hope, Upper Canada, son of Robert Armour and Marianne Burton; m. 30 March 1880 Alma Sarah Wossell Ponton (d. 1921) in Belleville, Ont., and they had three sons and three daughters; d. 3 Oct. 1922 in Toronto and was buried there in Prospect Cemetery.

Douglas Armour’s Scots grandparents on his father’s side immigrated in 1825 with the Robinson settlers [see Peter Robinson*] to Peterborough, Upper Canada, where the Reverend Samuel Armour founded the first Church of England parish. The family then turned to the law. Armour’s father, Robert, was a barrister and Conservative party activist in Bowmanville and Port Hope, and his uncle John Douglas Armour became chief justice of Ontario before being appointed to the Supreme Court of Canada shortly prior to his death in 1903. Sons and grandsons of Robert and J. D. Armour followed them into the Ontario legal profession.

Having graduated from Trinity College School, Port Hope, in 1869, Douglas Armour enrolled at Trinity College, University of Toronto, but soon left to focus on legal studies. He was called to the bar and admitted as a solicitor in 1876. He practised in Toronto with Alexander Leith, a specialist in real-property law, and eventually succeeded Leith as a local authority on that subject. For most of his career Armour was head of his own firm in partnership with Henry Walter Mickle and other lawyers. D’Alton Lally McCarthy*, later a prominent Toronto counsel, described Armour as a litigator much respected in real-property matters, with “a keen mind but perhaps a rather bitter tongue.”

Nineteenth-century law relied on self-education by lawyers, and Armour became a prolific member of the Ontario bar’s text-writing fraternity. A treatise on the investigation of titles to real estate in Ontario . . . (known as “Armour on titles”), one of several works he wrote, went through four editions between 1887 and 1925. In 1881, with the support of the Toronto legal publisher Carswell and Company, Armour had launched the Canadian Law Times, a magazine that provided case reports, theoretical articles, professional news, and commentary. Armour contributed news and editorials to almost every issue, usually asserting Olympian standards and looking sceptically at innovations. Pressure of work obliged him to pass the journal to other editors in 1900; in 1923 it was merged into the Canadian Bar Association’s Canadian Bar Review.

In his editorials Armour had advocated a centralized law school in Ontario run by the Law Society of Upper Canada. When the society opened such a school at Osgoode Hall in Toronto in 1889 [see William Albert Reeve*], he became one of its founding lecturers. Until 1910 he taught real-property law and constitutional law, while continuing his private practice and legal writing. He had been appointed a qc in 1890 and would receive an honorary dcl from Trinity College in 1902.

In 1889–90 Armour condemned Minister of Justice Sir John Sparrow David Thompson*’s refusal to disallow the Jesuits’ Estates Act [see Honoré Mercier*]. He argued in the Law Times that the bill posed a fundamental challenge to crown sovereignty by authorizing the pope to arbitrate a settlement among contending Roman Catholics in Quebec. In the Ontario provincial election of 1890 Armour unsuccessfully ran in Toronto as an independent Conservative in support of the Equal Rights Association, founded to resist Catholic influence in Canada [see William Caven*; D’Alton McCarthy*].

As Osgoode Hall’s lecturer in constitutional law, Armour taught students that the British North America Act established the central government’s authority over the provinces. He opposed legislative interference with private contracts (which he deemed sacred), believed English was the “race language” of Canadians, and was sarcastic about the entry of women into the legal profession.

Soon after retiring from his lectureship (but not his practice) in 1910, Armour was elected a bencher of the Law Society. (His uncle J. D. Armour and his cousin Eric Norman Armour, a Toronto lawyer and crown attorney, served as benchers at other times.) As chairman of the society’s legal education committee from 1915 to 1922, Armour was in effect the employer of his former colleagues at the law school. He supervised the waiving of educational requirements for law students who joined the military forces during World War I and helped initiate abbreviated summer courses to speed returned veterans into practice.

Late in life, Armour published two collections of poetry. Law lyrics (Toronto, 1918), which ingeniously recast long legal documents into rhyming couplets, satirized and celebrated the legal community. Echoes from Horace in English verse (Toronto, 1922) was a collection of rhymes inspired by the classical poet, some of which had first appeared in the new Canadian Forum (Toronto). They suggest cleverness more than substantial poetic gifts (“Achilles the haughty / Undoubtedly thought he . . .”). In 1921 Armour became a founding member of the Canadian Authors Association.

Armour had married Alma Ponton, from a Belleville legal family, in 1880. Their son Archibald Douglas joined the Armour and Mickle law firm and edited the 1925 posthumous edition of “Armour on titles.” A devout Anglican but sceptical about rigid Sunday-closing laws and other devotional extremes, Douglas Armour was a delegate to several synods of the Church of England in Canada. Upon his death in 1922 the Law Society honoured him as a man of strong will and a Christian gentleman.

The various editions of “Armour on titles” were published in Toronto in 1887, 1894, 1903, and 1925. Armour was also the author of A treatise on the law of real property, founded on Leith & Smith’s edition of Blackstone’s commentaries on “The rights of things” (Toronto, 1901; 2nd ed., 1916); Essays on the devolution of land upon the personal representative and statutory powers relating thereto: with an appendix of statutes (Toronto, 1903); and “Notes on Canadian statutes,” in the 7th edition of H. S. Theobald, A concise treatise on the law of wills (London, 1908). In addition, he was the editor of Reports of cases argued and determined in the Court of Queen’s Bench in Manitoba both at law and in equity, and some cases determined in the county courts during the time of Chief Justice Wood, from 1875 to 1883: being principally judgments of the chief justice (Toronto and Edinburgh, 1884).

AO, RG 80-5-0-89, no.4084; RG 80-8-0-858, no.5606. Law Soc. of Upper Canada Arch. (Toronto), 1-1 (Convocation, minutes), 1911–22, esp. 23 Nov. 1922; M259 (W. G. C. Howland fonds), D. L. McCarthy, draft autobiography; Curtis Cole, “A history of Osgoode Hall Law School, 1889–1989”; Ontario bar biog. research project database. Trinity College Arch. (Toronto), Student records, 1869–70. Globe, 4 Oct. 1922. Toronto Daily Star, 4 Oct. 1922. The Canadian law list (Toronto), 1876–1922. Canadian Law Times (Toronto), 4 (1884): 232; 8 (1888): 69, 276; 9 (1889): 231; 12 (1892): 111. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1912). Directory, Toronto, 1906–28. J. R. Miller, Equal rights: the Jesuits’ Estates Act controversy (Montreal, 1979).

Cite This Article

Christopher Moore, “ARMOUR, EDWARD DOUGLAS,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 1, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/armour_edward_douglas_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/armour_edward_douglas_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | Christopher Moore |

| Title of Article: | ARMOUR, EDWARD DOUGLAS |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2005 |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | January 1, 2026 |