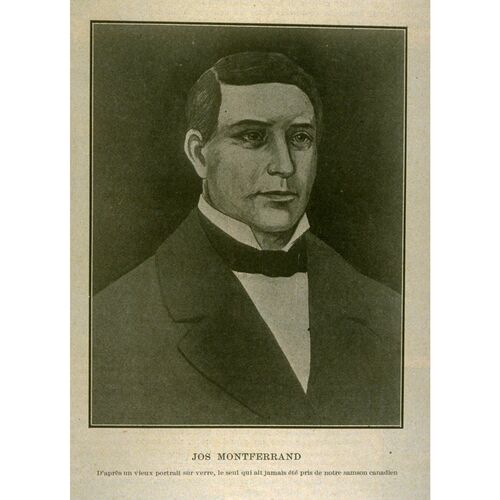

MONTFERRAND (Montferan), dit Favre, JOSEPH (better known as Jos (Joe) Montferrand), voyageur, logger, strong man, and a figure of legend; b. 25 Oct. 1802 at Montreal, son of François-Joseph Favre, dit Montferrand, voyageur, and Marie-Louise Couvret; d. 4 Oct. 1864 in his native town.

Joseph Montferrand, dit Favre (the Favre comes from his grandfather François Favre, dit Montferrand), belonged to the third generation of Montferrands in Canada. His grandfather, a soldier in the troops of the Chevalier de Lévis*, had settled at Montreal after the conquest of New France and opened a fencing salon. Powerfully built and renowned for strength, the Montferrands acquired a certain fame in the working class districts of Montreal, whose people made a fetish of physical skill and strength. According to Benjamin Sulte*, the faubourg Saint-Laurent where they lived had “some ten boxing halls and many taverns” in which foreign sailors and voyageurs engaged in combat, under the amused gaze of idle bystanders, sometimes including soldiers and citizens, who shared the popular love of the “noble art.”

It was in this cosmopolitan, picturesque faubourg that Joseph Montferrand grew up. He was supposed to have learned the shorter catechism from his sister Hélène (he also had two brothers) and the art of foot fighting and boxing from his father, but his sister was born on 9 Nov. 1804 and his father died prematurely on 16 Sept. 1808. Joseph’s natural gifts quite early won him respect as a boulé (from the English “bully”). At 16, Montferrand had almost reached his full height. Six feet four inches tall, he had a clear complexion, blue eyes, and fair hair, and did not look at all like a ruffian. His contemporaries seem to have been struck by the regularity of his features and his distinguished bearing. It was not so much his physical strength as his agility and litheness that were impressive. By trade he was a carter. Around 1818 he established himself as the cock of the faubourg Saint-Laurent by thrashing three hooligans who were terrorizing the neighbourhood. At the same period, before a crowd of boxing enthusiasts on the Champ de Mars, he took on an English boxer who had declared himself champion and had challenged him. With one punch he knocked him out. In 1820 or 1821, on his way through Kingston, Upper Canada, where his work as a carter had taken him, he beat a mulatto boxing instructor who was greatly admired by the garrison. These two exploits brought him fame. People began to say that Jos Montferrand “struck like the kick of a horse,” and that he “used his leg like a whip.”

Montferrand, along with many young people around him, was drawn to the west by the tales of the voyageurs who came to spend their money in the inns of his neighbourhood. In 1823, at the age of 21, he signed on with the Hudson’s Bay Company, but nothing is known of his activities during his four years with it. In 1827 he became an employee of Joseph Moore, who was exploiting the pine forests of the Rivière du Nord, in Lower Canada. Subsequently he worked for Baxter Bowman, a lumberman with camps on the upper Ottawa River. In turn foreman, crib guide, and trusted agent of his employers, Montferrand lived a logger’s adventurous life for 30 years. In the autumn he would leave Montreal with his men to proceed to the upper Ottawa, stopping at all the many taverns along the route. For months on end the men were busy felling trees, getting up at dawn and slaving away until nightfall. In spring the woodcutters became “raftsmen.” Then the logs were driven down towards the lower Ottawa, where they were collected into cribs to be steered with the currents as far as the port of Quebec. The men lingered at Montreal and Quebec, where they were always ready to show off their strength and skill, and when the occasion arose to hire out their talents to the organizers of elections.

Montferrand enjoyed this roving life, which led him to spend part of his time in the “tough spots” of Lower Canada: the lumber camps, ports, and taverns, where the law of the strongest prevailed and where the fighters of each ethnic group valiantly defended the honour of their race. Because he was the strongest and quickest, Montferrand was king. But king though he was, he constantly had to defend his crown. On more than one occasion he had to take up a challenge or extricate himself from an ambush. His adventurous life was studded with exploits in which skill, speed, and strength were of prime importance. In 1828, on the Quai de La Reine at Quebec, Montferrand is said to have beaten a champion of the Royal Navy in the presence of a large crowd. The following year, on the oak bridge leading from Hull to Bytown (Ottawa), he managed, according to legend, to rout a band of “Shiners” [see Peter Aylen] 150 strong. During the violent by-election of May 1832 at Montreal, he put to flight a band of braggarts who were threatening his friend Antoine Voyer; the latter, with one blow of his fist, had instantly killed an adversary whom Montferrand had once thrashed. In 1847, again at Montreal, he defeated a man by the name of Moore who was an American boxing champion. But later there were fewer such exploits.

No doubt Montferrand was feeling the weight of his years: from 1840 on he no longer went to the upper Ottawa region; he was content in spring and summer to direct the raftsmen who brought the cribs down to Quebec. Around 1857 he retired to Montreal to a house on Rue Sanguinet. He was only 55 but had declined physically; his back was bowed from constant rheumatic pain. But he was still king of the Ottawa River, and in his faubourg was worshipped as a hero. On 28 March 1864, Montferrand, whose first wife Marie-Anne Trépanier had died, married Esther Bertrand; after his death she bore him a son, Joseph-Louis, who grew to be as tall as his father. Montferrand died at his home on 4 Oct. 1864.

Well before his death, Montferrand was enshrined in a legend that was to embellish his life and magnify his exploits. The hero of this legend had two destinies, one given him by the oral tradition of folklore, the other by writers. Even in his lifetime, perhaps before the 1840s, Montferrand was a hero whose deeds were exaggerated in taverns, logging camps, and at home. André-Napoléon Montpetit was to write: “Before I was eight years old Joe Montferrand had captured my imagination, his French Canadian personality blotting out the fanciful figures of the stories by [Charles] Perrault.” Wilfrid Laurier* had written in 1868 that “no name, after that of the great Papineau [Louis-Joseph*], has become more popular, wherever the French language is spoken in the land of America.” The most notable feats oral tradition seems to have attributed to him are routing the best known English, Irish, Scottish, and black bullies, scattering 150 “Shiners” on the bridge from Hull to Bytown, impressing his heel-mark on tavern ceilings by a fantastic somersault, and lifting his plough at arm’s length with one hand. It is impossible to be precise about all these exploits, since no one knows to what extent Sulte’s work, which was widely read, influenced the oral tradition. Montpetit wrote that “the popular panegryists have taken advantage of it [the tradition] to credit him with a host of stories and similar valorous deeds completely unconnected with him, while wantonly misrepresenting and distorting his real exploits.” The Montferrand of tradition owes a lot to our innate need for the fanciful and the marvellous, but it is virtually certain that many of this hero’s feats were designed to increase the self-esteem of the community and to exorcize popular fears. Heroes are for small groups what self-images can be for individuals.

As there is no collection of legends, it is impossible to follow the development of the oral tradition. Laurier, in 1868, was the first prose writer to attempt to popularize the hero. His work marked the beginning of Montferrand’s third life, in which he was neither a real person nor a creation of folklore, but a popular figure whose image was transmitted first by the printed word (Montpetit, Sulte, etc.), then by the theatre (Louis Guyon*), then by song (La Bolduc [Mary Travers*], Gilles Vigneault). As a popular figure Montferrand came to embody the ideals, ethics, and aspirations of the French Canadian community. These writers retained and emphasized elements of the oral tradition which corresponded most closely to their vision of French Canadian society. The Montferrand of Montpetit and Sulte is the prolongation of the élite’s clerical, rural, and nationalist ideology. He is not quite an altar boy but certainly resembles one. He has a gentle nature, he displays piety in his childhood, and when he makes his first communion a Sulpician points him out as an example. He has great trust in God and profound reverence for the Virgin Mary, and knows instinctively that he must only use his strength to redress wrongs and punish the wicked. He protects the children of his neighbourhood, and later the widows. He collects alms for the destitute and for those in prison. He does not like brawls, “but subordinates his temper to the dictates of the law and justice.” The miscreants he chastises are always enemies of religion or the country or the people. If he accepts a challenge for honour’s sake, he hands the takings of the fight to his defeated opponent. To those who suggest that he should take revenge, he replies: “I much prefer to forgive than to avenge.” The real Montferrand had a weakness for the fair sex, but Montpetit keeps silent about his nocturnal gallantries “in order to display our hero against a background of poetry and light.” For his part, Sulte proceeds to make this voyageur the prophet of colonization: on Bowman’s farm at the Lac des Sables, near the Rivière du Lièvre, Montferrand is said to have urged that new territories be conquered, “otherwise the English will crush us.” Thus 19th century writers sanctified and nationalized Jos Montferrand, just as the church sanctified popular festivals, place names, church and charitable groups, and the French Canadian society as a whole.

Both the stories of lumberjacks and the written material distributed by certain lumbering companies spread the legend and the popular tales through the forests of North America from Newfoundland to British Columbia. Sometimes Montferrand squares the Laurentian forests, sometimes he takes a roller to the plains of Saskatchewan, sometimes he notches a maple 600 feet high. George Monteiro has analysed the Montferrand legend in the United States. It is thought to have been imported by French Canadian immigrants to New England around the 1870s. Only at the turn of the century, apparently, did it spread to the tree-felling centres in Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota. The hero was called Mouffreau, Mufferon, Maufree, Murphy, etc. Monteiro accepts Max Gartenberg’s theory that W. B. Laughead of the Red River Lumber Company first associated Montferrand with the celebrated Paul Bunyan, the legendary American hero, in material written for the company. It widely distributed Laughead’s writings, in which Montferrand is reduced to the role of Bunyan’s cook. This assimilated Montferrand bore little resemblance to the hero of the Canadian legend: “Joe Le Mufraw was enormously squat, shaggy, and wide. His feet and legs bulged like two mammoth black stumps sawed close to the ground . . . [He] was a man without a neck. His head merged with his shoulders like a black camel’s hump.”

The Montferrand legend creates two problems for historians. The first is to understand why French Canadian society valued strong men and physical strength so highly. Our hypothesis would be that the more a society feels weak and threatened the more it clings to giants. Legends are not simply a means of repression in society, but also serve to heighten a sense of importance, even to exalt. Between the situation of the French in North America and their cult of the strong man there is more than mere coincidence.

The second problem is to ascertain why, among the ten or so strong men credited with what were often legendary exploits, Montferrand so attracted the popular imagination and the attention of writers that he became an exemplary figure and in certain respects acquired the quality of myth. Laurier proposed an answer in 1868: “The secret of this popularity is that Joe Montferrand combined all the features of the national character, each as completely developed as humanly possible. In him undaunted bravery, muscular strength, thirst for danger, resistance to fatigue – the distinctive qualities of the race 50 years ago – were heightened to an almost miraculous degree. In a word, Joe Montferrand was the most truly Canadien of all Canadiens ever known.” We can see three reasons: the personality of the hero, the place of his exploits, and the period in which he lived. Montferrand, an athlete endowed with a fine physical presence, who had never been on exhibition in a circus, was an engaging figure in his lifetime. The fact that a fair number of his deeds of valour were performed against the “Shiners” or the Orangemen in the Ottawa valley, which for 50 years was a no man’s land where Irish and Canadiens, Catholics and Protestants, English merchants and French settlers were pitted against one another, made it possible for him to become a symbol at a time when a national ideology based on faith and language was about to be formulated. Because his exploits belonged to the period which saw the disappearance of the coureur de bois and the voyageur, and the suppression of the Patriotes by British soldiers, he was a proper hero for a nostalgic and anxious people in search of a symbol onto which it could project its fears, frustrations, and dreams. Unable to realize their visions, French Canadians, between 1840 and 1880, built a symbolic country in their ideology, their legends, their literature, and their art. In the struggle they continued to wage against the English and against nature, French Canadians found hope and greater self-respect in the Montferrand legend.

The legend has not died out. It still lives in town and countryside, and reappears with more vigour than ever in difficult periods. During the crisis of the 1930s, it was perhaps Montferrand that La Bolduc revived under the name Johnny Monfarleau. Early in the quiet revolution, the poet Gilles Vigneault made Montferrand a philosopher sitting on Cap Diamant. This new Montferrand, very different from the hero of preceding generations because he reflects the new values of Quebec culture, continues none the less to be a part of the symbolic country.

[Jos Montferrand still awaits his historian or folklorist. In the present state of research, it is impossible to distinguish clearly history from legend and to give their true proportions to both the voyageur and the figure of folklore.

This description of the real individual and of the legendary hero is based on Benjamin Sulte, Histoire de Jos. Montferrand, l’athlète canadien, published in Montreal in 1899. Sulte’s text went through several editions prior to 1899: a first edition probably in 1883, a second in 1884, a third in the Almanach du peuple (Montréal) in 1896. Since 1899 Beauchemin of Montreal has evidently published several popular editions of Sulte’s text. The reader should, however, consult Sulte’s article entitled “Jos. Montferrand,” which Gérard Malchelosse* annotated and published in volume XII (1924) of Mélanges historiques (21v., Montréal, 1918–34). In it Malchelosse provides the dates of the hero’s genealogy and life. Further material was found in the anecdotal work of André-Napoléon Montpetit, Nos hommes forts . . . (Québec, 1884), of which certain passages were published in L’Opinion publique of 9, 16, 23, 30 Nov., 7, 21 Dec. 1871, and 25 Feb. 1875, as well as in Le moniteur acadien (Shédiac, N.-B.) of 3 and 10 Nov. 1881. Sulte borrowed from Montpetit, who had known Montferrand around 1863, probably through Montferrand’s second wife, Esther Bertrand, who had been brought up by Montpetit’s uncle.

Around 1866 young Wilfrid Laurier amused himself while resting at L’Avenir, Lower Canada, by writing a biography of Montferrand. To his friend Médéric Lanctot* he noted: “These stories were about Joe Montferrand, and one day I perceived that unwittingly I had recounted almost the whole life of the famous voyageur.” He gave his friend the task of publishing them in instalments in the weekly L’indépendance canadienne (Montréal), which, after two issues–22 and 25 April 1868 – apparently ceased publication. We only have the introduction to the biography which contains a picturesque description of the town of Montreal. In the review Asticou (Hull, Qué.), no.8 (déc. 1971), 27–34, Gilles Lemieux published with an introduction “La vie de l’illustre Joe Montferrand par sir Wilfrid Laurier.” It is regrettable that we do not have the other parts of Laurier’s article, which seems to be the first biography of Montferrand based on the oral tradition. Judging by the text of Laurier quoted above, it would appear that his biography follows that tradition more closely than those of Montpetit and Sulte, and that it was not influenced by the post-1850 clerico-nationalist ideology. Ludger Gravel*’s Recueil de légendes illustrées (Montréal, [1896]) and the articles on Montferrand in magazines and in the weekend press seem to be watered-down versions of Sulte’s work. We note also that Louis Guyon composed a play about Montferrand in 1903.

Jean Du Berger of Université Laval, who has kindly read this article, presents some of the oral traditions relating to Montferrand in his “Introduction à la littérature orale” (roneoed copy, Québec, 1971). In “Histoire de Montferrand: l’athlète canadien and Joe Mufraw,” Journal of American Folklore (Philadelphia), 73 (1960), 24–34, George Monteiro makes an interesting analysis of the Montferrand legend in the United States. Finally, the dates of birth, marriage, and death of Montferrand and his family have been checked in the ANQ-M, État civil, Catholiques, Notre-Dame de Montréal. g.g. and j.h.]

Cite This Article

Gérard Goyer and Jean Hamelin, “MONTFERRAND (Montferan), dit Favre, JOSEPH (Jos (Joe) Montferrand),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 9, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 25, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/montferrand_joseph_9E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/montferrand_joseph_9E.html |

| Author of Article: | Gérard Goyer and Jean Hamelin |

| Title of Article: | MONTFERRAND (Montferan), dit Favre, JOSEPH (Jos (Joe) Montferrand) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 9 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1976 |

| Access Date: | April 25, 2025 |

![Jos Montferrand [image fixe] Original title: Jos Montferrand [image fixe]](/bioimages/w600.3986.jpg)