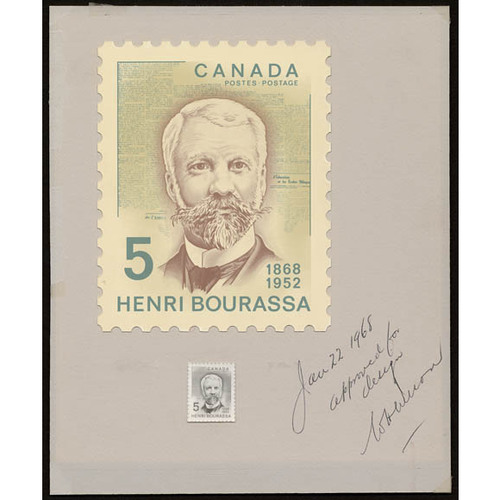

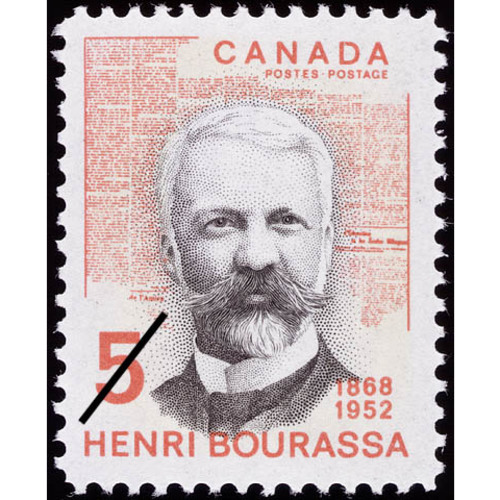

BOURASSA, HENRI (baptized Joseph-Henry-Napoléon), politician, journalist, newspaper owner, editor-in-chief, publisher, and author; b. 1 Sept. 1868 in Montreal, son of Napoléon Bourassa* and Azélie Papineau; m. 4 Sept. 1905 his distant cousin Joséphine Papineau in Sainte-Adèle, Que., and they had eight children, six of whom outlived him; d. 31 Aug. 1952 in Montreal.

Originally from Poitou, France, Henri Bourassa’s paternal and maternal ancestors came to New France at the end of the 17th century. According to some sources, it is thought that they were initially soldiers. Among their descendants were a number of commanding figures in Henri’s life. In the Bourassa family, there was first of all his bilingual grandfather, François, a strong personality who enjoyed controversy; conservative both politically and socially, he had vigorously opposed the Patriotes in 1837. Then there were three of his sons. The eldest, also named François*, was a liberal and made his mark in the family by joining the Patriotes in 1838. Elected to the provincial parliament in 1854, he sat without interruption in it and in the House of Commons until 1896. After that, there was Augustin-Médard, an Oblate missionary among aboriginal peoples and later, from 1858 to 1888, curé of the seigneury of Petite-Nation (which had become Montebello). An unyielding ultramontane with a caustic wit, he gave young Henri the run of his library, and his reading would encompass the works of Louis Veuillot, Joseph de Maistre, and Jules-Paul Tardivel* (through the pages of his newspaper, La Vérité), authors who became the principal influences on his thinking. “It was there,” Henri affirmed on 13 Oct. 1943, in the first of the talks devoted to his political and journalistic “Mémoires,” “in my uncle’s library and in reading L’Univers, that I found my lifelong ideas about the role of the church in society [and] the relationship that ought to exist between the church and the secular authorities.” Lastly, there was Henri’s father Napoléon, the artist of the family. He took little interest in politics in 1868, the year Henri was born, but this would not prevent him from offering advice to his son later on. From this “very good father” he inherited an “innate taste ... for artistic things, for music [and] painting.” On the Papineau side, there were lively and even more interesting personalities. First and foremost there was Henri’s illustrious grandfather, Louis-Joseph*, who, in 1868, was enjoying his final years in part at the luxurious manor of Montebello. Bourassa would say in 1943 that he had acquired from him “the temperament of an orator and an unconquerable independence of character, a congenital inability to say what I do not think and not to say what I do think.”

Some six months after Henri was born, his mother died of severe “brain fever.” For Napoléon and his children, life was turned upside down. Aunt Ezilda Papineau took over, sometimes in Montreal in the winter, sometimes at Montebello in the summer, in the homes belonging to grandfather Papineau. Following Louis-Joseph’s death in 1871, Napoléon would occasionally rent a house in Montebello, or rooms in Augustin-Médard’s presbytery, for the summer. An energetic and disciplined woman, Ezilda was young Henri’s first teacher. As an ultramontane, she brought him up to revere Pope Pius IX and Bishop Ignace Bourget* of Montreal. She had him read the Bible and then Sir Walter Scott and James Fenimore Cooper. In Montreal, Henri often went with his father to the homes of friends, where problems of the day were discussed. The boy, who by the age of nine had read Émile Keller’s Histoire de France and when he was 12 would read the French translation of John Lingard’s massive History of England, took great delight in listening to these debates.

Bourassa began his studies in Montreal in 1876-77 at the Institution des Sourdes-Muettes, after which he took private lessons from Jane Ducondu for two years. In 1879 he enrolled in the Catholic Commercial Academy in Montreal, where he spent two and a half years. The regime at the school was a little too structured for his liking, although Bourassa would acknowledge in 1943 having “acquired the basis of all my beliefs and religious practices” there. From 1882 to 1885 he was instructed by two private tutors, the more important of whom was Frédéric André, a cultivated Frenchman and excellent pedagogue, who taught him to be open to nature and new horizons, and to give himself wholeheartedly to his inclination to learn on his own. This burst of enthusiasm led him to enrol at the École Polytechnique in 1885. However, because of mental exhaustion, and, apparently, a religious crisis, he left the institution after a month. In September 1886 he went to Holy Cross College in Worcester, Mass., to perfect his English and finish his classical studies. He left after one trimester, once again for reasons of health. Henri’s academic career came to an end at the age of 18, although he would be drawn to the study of law between 1897 and 1903 he would neither have a profession nor be a priest. A self-educated man by then, he had not been subjected to the often narrowing conformism of the classical colleges of his day. He had acquired a taste for reading a broad range of subjects, for critical thinking, and for closely argued debate. He now entered a period that would establish the main interests of his life.

This period, from 1887 to 1896, saw Henri turn towards three new activities. While continuing to further his education by reading voraciously, in 1887 he began to take charge of the seigneury of Petite-Nation, which the Bourassas, along with his aunt Ezilda and his uncle Louis-Joseph-Amédée Papineau, had inherited at the death of Louis-Joseph. That year Napoléon made him responsible for administering the part of the estate bequeathed to the Bourassa children. This duty gave Henri an opportunity to learn about problems related to small farmers, colonization, and local institutions. He set up, probably between 1887 and 1890, a model farm that he would continue to work until 1898. In 1893 he won the Medal of the Order of Agricultural Merit and became president of the Ottawa county agricultural society. He even helped establish settlers in what would become the parish of Notre-Dame-de-la-Paix in 1902, and was elected churchwarden in 1893 and syndic in 1894 of the parish of Notre-Dame-de-Bon-Secours. A man of action, Henri built up a storehouse of knowledge and created an ideal political springboard for himself.

Bourassa had politics in his blood – it was his second activity. His passion had been triggered by the Riel affair [see Louis Riel*] in 1885. Like French-speaking Quebecers, he had been outraged by the hanging of the Métis leader and he was stirred by the speeches of Honoré Mercier* and Wilfrid Laurier* in Montreal’s Champ-de-Mars on 22 November. By the time Laurier became leader of the Liberal Party of Canada on 18 June 1887, Bourassa had developed great admiration for him. From then on he prepared for his move upward into federal politics. In January 1890, at the age of 21, he was elected mayor of Montebello, an office he held successfully until 19 Feb. 1894. He then took part in political campaigns during which he revealed his gifts as an orator, with a strong though somewhat piercing and high-pitched voice and impeccable diction. Word of him spread so rapidly that in the winter or at the beginning of the spring of 1895 the Liberals in the riding of Labelle nominated him as their candidate for the federal election expected in 1896. He would immediately make his views known: “The right to vote with or against my party, according to my convictions” and a point-blank refusal to be financed by the party. Laurier, who reportedly had known him since childhood, turned a blind eye to his rather free spirit. This period marks the real beginning of the connection between these two exceptional men who shared a mutual fascination for each other and who were fated to reach a parting of the ways.

To ground his political aspirations more securely and to stay in touch with public debates, Bourassa devoted himself in these years to a third activity: journalism. In 1892 he became “publisher-owner” of L’Interprète (Montebello), a weekly created in 1886 that was dedicated to the interests of the riding of Labelle and Franco-Ontarians [see François-Eugène-Alfred Évanturel*]. On 11 April 1895, from the vestiges of this publication, he and a number of others launched Le Ralliement (Clarence Creek, Ont.), which he would continue to publish until 3 June 1897. Already, in the pages of these two newspapers, the depth of his thinking, his skill as a writer, and his mastery of the crushing retort, indeed, even his immoderate language, are evident. Here the man of principle emerges, obedient to the Roman Catholic Church and dedicated to defending the rights of French Canadians, which, he maintained, were “guaranteed by the treaties and constitutions.” One problem above all stirred his passion at that time: the Manitoba school question [see Thomas Greenway*; Sir Wilfrid Laurier]. He wrote article after article decrying the inaction of federal MPs since 1890, demonstrating the constitutional obligation to restore the rights of the Catholic minority in that province, and proclaiming the “wisdom” of the “noble” and “worthy” Laurier, though he recognized his leader’s ruses. To the bishops who were restive, especially after the Conservatives introduced their remedial legislation on 11 Feb. 1896, Bourassa retorted that he was always ready to listen to them on spiritual concerns, but that on political and civil matters he remained free to decide for himself.

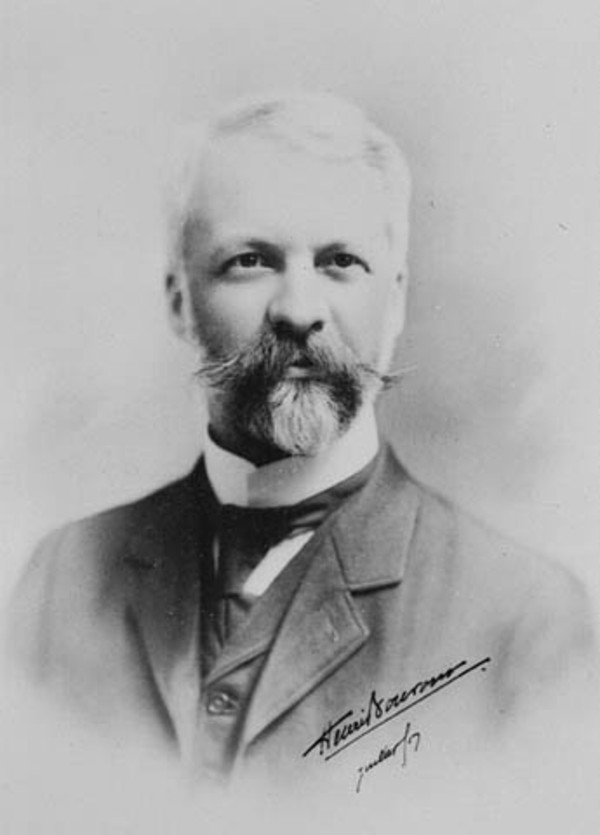

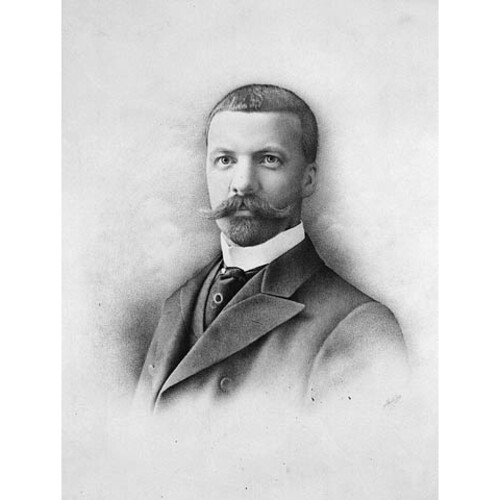

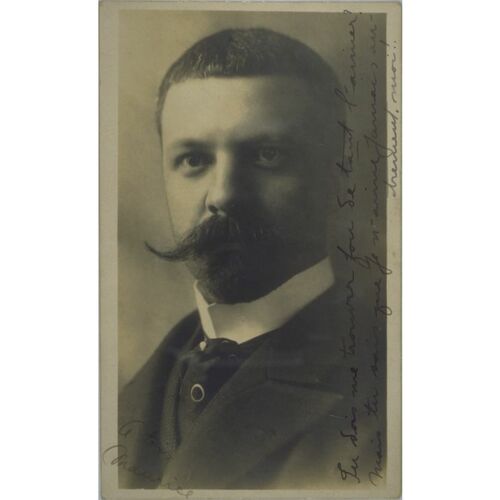

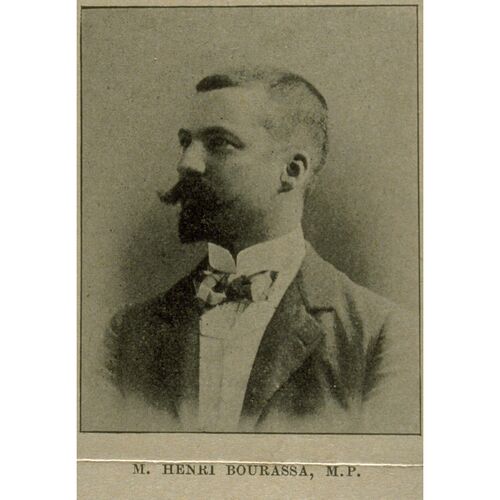

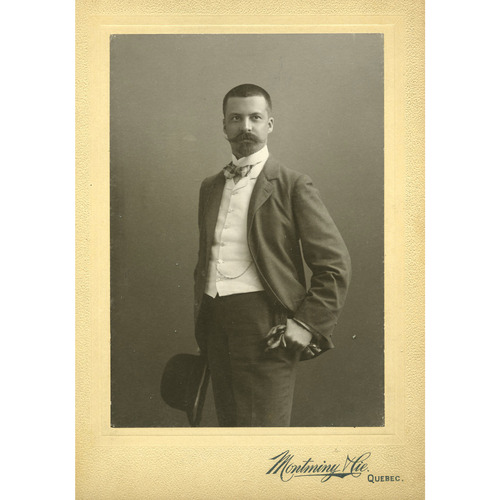

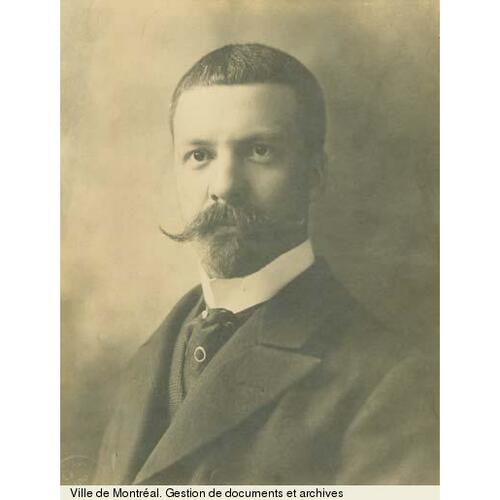

On the evening of 23 June 1896, after an intense campaign during which he discussed the Manitoba school question, among other issues, Bourassa shared in the victory of Laurier’s Liberals. At the age of 27, he was elected in Labelle by 469 votes. It was a euphoric time for him. As his leader’s protégé, gifted with exceptional powers of oratory, and bilingual, he had the talent, culture, and work ethic to succeed. Although he made no secret of his ultramontanism, he also openly declared himself a liberal, of the moderate cast of liberalism promoted by Laurier since 1877. A Castor Rouge: such would be the prime minister’s caricature of him. He had self-confidence. Living off the income from farming and from his land, as well as the inheritance of the Papineaus, which was assessed at some $24,000 in 1894, he had made his home since then in Papineauville, where he resided in moderate comfort and would serve as mayor from 1896 to 1898. (He and some associates would open a sawmill there in 1898.) A man of medium height, with short black hair, a large moustache, and a Vandyke beard, he cut a haughty figure, with his refined elegance and somewhat solemn presence. His piercing, intimidating eyes revealed a determined individual, ready to assume whatever destiny lay ahead.

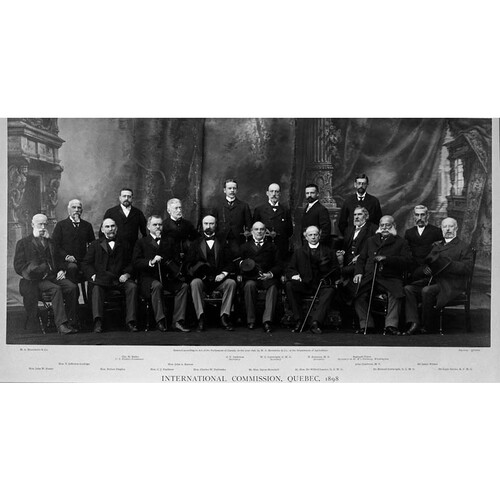

Bourassa could not hope for a portfolio in Laurier’s cabinet, but the prime minister soon bestowed on him three marks of confidence. First, he sent him to Manitoba with Joseph-Israël Tarte*, the minister of public works, to negotiate an agreement on the delicate school question. Laurier counted on linking Bourassa in this way to the hoped-for accord. When the Laurier-Greenway agreement, which offered only crumbs to the minority, was made public on 19 Nov. 1896, Bourassa could not distance himself much from it. He accepted it as an honourable compromise, “a step on the path of justice.” In the face of the outcry from the bishops, he is believed to have written a request to Rome, on Laurier’s behalf, to have a delegate come and study the question on the spot. This was the assignment taken up in March 1897 by Monsignor Rafael Merry del Val, who met the young mp and assigned him the task of being vigilant in the House of Commons. In December the encyclical Affari vos would ratify the Laurier-Greenway compromise, with some qualifications. Bourassa thought at the time that his opinions had been confirmed by Rome, but the ensuing events would drive him to despair. Laurier’s second mark of confidence in his mp had to do with his profession as a journalist. Early in 1897, through the good offices of Tarte, who had just bought La Patrie, the prime minister had Bourassa made editor of this influential Montreal daily in hopes of moderating its radical liberalism. Flattered, the young parliamentarian decided to turn it into an ultramontane paper championing moderate liberal ideas in politics. It did not take long, however, for this hope of reconciling his ultramontanism, independence, and membership in the Liberal Party to founder. After only eight days, and one editorial, he resigned, a step precipitated by the revolt of the party’s old guard and a disagreement with Tarte. This disappointment, especially on top of the preceding one, led him to take a crucial decision, as he would affirm in 1930: in all matters, “I resolved from that moment to obey the Pope.” The ultramontane won out permanently over the liberal. Then there was Laurier’s third gesture. In 1898, with the obvious intent of exposing his young protégé to international issues, he made him one of the secretaries of the Anglo-American joint high commission to settle disputes between Canada and the United States, including that of the Alaska boundary. Bourassa discovered the game of quiet diplomacy, the world of high society, and his own interest in international questions and the men who guide their destinies. Even though the discussions collapsed in the face of American intransigence on 20 Feb. 1899, Bourassa was seized by a passion that would never leave him. Then, in April he made a speech in Ottawa, which he would repeat in Montreal in May, castigating the budding feminist movement and urging women to shun public office and devote themselves to home and family.

On 13 Oct. 1899, without consulting parliament, Sir Wilfrid Laurier agreed to send Canadian volunteers to South Africa to support Great Britain in its war against the Boers. Canadian participation squarely posed the question of Canada’s status within the empire and its contribution to imperial wars. British imperialism, ever present as background, prompted two different visions of the country’s future [see Sir Wilfrid Laurier]. What would Bourassa do? Moved by a religious conscience averse to concessions, he resigned from the commons on 18 October. In his view, sending troops set a precedent that made a mockery of the traditional political relations between Canada and the empire. Even worse, by going against the constitution, the government had relegated the country to the status of a simple colony dependent on England. Participation in imperial wars should take place only if Canada were represented on the councils of the empire, if parliament and the Canadian electorate were consulted, and if the country were threatened. Suddenly there was a crisis in Ottawa. Laurier tried to appeal to his good sense in order to dissuade him, but without success. Despite genuine and mutual affection, their relationship clouded over. Bourassa went around his riding to present his point of view and to secure his re-election by acclamation as an independent on 18 Jan. 1900. On 13 March he forcefully resumed his arguments in his first major speech in the House of Commons. Laurier made a brilliant reply and had enough effect on the members that they easily defeated Bourassa’s motion, which incorporated his thinking since 18 October. Nevertheless, the fact remained that a political star had been born. Henceforth, Bourassa, who retained his seat in the general election of 7 Nov. 1900, had a mission in life: to create enlightened public opinion by communicating to Canadians a clearer understanding of Canada’s relations with the empire and the nature of the relationship between the country’s English Canadian Protestant majority and its French Canadian Catholic minority.

A pragmatic man, Bourassa developed a strategy to achieve this end that bore witness to his political acumen. He would create a network of friends, promote political campaigns, become well informed in order to produce articles and speeches, and use the press. Among his supporters, one man stands out: Jules-Paul Tardivel, with whom he carried on a regular correspondence. Tardivel offered him space in the columns of La Vérité. Beginning in March 1900 the two men even considered founding a third party, which would be anti-imperialist and independent, but Bourassa would abandon this unrealistic idea. Besides Tardivel and individuals such as Goldwin Smith* of Ontario, Bourassa attracted the young francophones of Quebec, who were tired of the old parties. Some of them, full of progressive ideas, worked at Les Débats (Montréal) until 1903. That year, others organized the Association Catholique de la Jeunesse Canadienne-Française and especially the Ligue Nationaliste Canadienne, which was led by Olivar Asselin*, Armand La Vergne*, and Omer Heroux*, to whom Bourassa was particularly helpful. Thus was born a popular educational movement, the Nationaliste movement, which promoted a defined program [see Olivar Asselin] and organized the political campaign for the mp from Labelle. As an individualist anxious to maintain his independence, Bourassa would not become a member or a leader of either group.

During these years, Bourassa became more knowledgeable about the British empire. In 1901 he went to London, where he met a number of important figures, both pro-imperialist and anti-imperialist, and then to Ireland and Scotland. On 20 October, shortly after his return, he delivered a speech in Montreal about Great Britain and Canada in which he scathingly attacked British imperialism. He nevertheless refused to opt for Canadian independence because of the lack of unity between its two peoples, French and English, or for annexation to the United States, proposing instead to “strengthen and broaden [Canadian] patriotism.” In another speech, given in Montreal on 27 April 1902 and reprinted in La Revue canadienne (Montréal), under the heading “Le patriotisme canadien-français: ce qu’il est, ce qu’il doit être,” he gave further shape to his budding nationalism. He began by arguing that French Canadians ought to love Canada, which he described as a “geographical absurdity” that must nonetheless be protected against any vague desire of its constituent parts to separate. He urged them to respect the double contract made with English Canadians in 1867: first, the national contract that declared French and English Canadians to be “partners with equal rights,” and secondly, the political contract that had as its goal the unification of the scattered colonies of British North America. This was the first time since 1895 that he spoke openly about this pact. Then he identified the distinctive characteristics of the French Canadian race that had to be safeguarded: the Catholic religion, central to everything, the French language, and the traditions, history, and institutions. He touched on some social aspects that underscored his conservatism: the importance of the elite, and the moral weight of the masses, who should not speak English, receive too much education, or earn a lot of money. Showing a slight progressive leaning, he called for the updating of curricula and the creation of secondary schools for teaching trades and business subjects. On 3 April 1904, when Tardivel’s La Vérité and Le Nationaliste, the organ of the Ligue Nationaliste Canadienne, diverged in their views, he summed up his opinion: “The fatherland, for us, is Canada as a whole, that is to say a federation of distinct races and autonomous provinces. The nation ... is the Canadian nation, composed of French Canadians and English Canadians.” This was the heart of his nationalist thinking, which he would flesh out by degrees, especially in the social sphere. He was imbued with these ideas on the eve of the 1904 election, while Laurier, who was once again his leader, was extolling his policy of developing the country. But Bourassa, who was re-elected in November in a transformed Canada, would soon face another nightmare.

By the beginning of 1905, Bourassa had become a politician of considerable stature. In his own province he was even seen as a possible cabinet minister at Quebec, indeed as leader of the government. He was hoping instead to become deputy speaker of the House of Commons or postmaster in Montreal, where he was living at the time. Laurier needed him, however, for the main project of his third term: carving the provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan out of the Northwest Territories. This undertaking involved a major problem: the system of education to be given the two provinces. The prime minister wanted to preserve the separate schools of the small Roman Catholic minority. Without the knowledge of his senior English-speaking ministers, he drew up legislation, along with Charles Fitzpatrick*, his minister of justice and attorney general, and consulted Bourassa. On 21 February he introduced a bill giving concrete expression to his wishes. Bourassa and La Vergne were overjoyed. For English-speaking Canada, it precipitated a crisis. The powerful Clifford Sifton* resigned and other ministers threatened to follow suit. Laurier procrastinated, while Bourassa urged him to hold firm. The prime minister opted for compromise, thereby in effect destroying the separate school system. In the House of Commons, Bourassa openly rebelled and moved or seconded one amendment after another, all of which were defeated. On 17 April he held a huge meeting in Montreal at which he stood out as the leader of a minority seeking justice and moral support. Laurier’s image was damaged. Yet Bourassa’s efforts achieved little for the victimized minority. He came out bruised, disappointed with his leader – from whom he again distanced himself – but especially with the Liberal caucus and the Liberal press. While he stayed on in Ottawa until October 1907, mainly to criticize immigration policy, it was the provincial scene that attracted him from now on.

This move to the provincial scene, “the biggest mistake of my public life,” Bourassa would declare in his “Mémoires,” was prompted mainly by an awareness of the economic and social problems that Quebec was then experiencing. The province was becoming industrialized and urbanized, while the Liberal government of Lomer Gouin*, rather like a business, was sometimes tainted with corruption. In the summer of 1907, with the strong backing of Le Nationaliste and the support of La Vergne, who was becoming his leading disciple, Bourassa denounced the mismanagement of colonization and natural resources. He held numerous meetings and displayed the slogan “Free land for free settlers.” He revealed some of the elements of his economic thinking: opposition to monopolies, as well as to socialism and communism; acceptance of free enterprise and even of trusts, whose practices must be well defined; government ownership and control of public utilities, in conjunction with private enterprise; moderate tariffs to help industry; and support for the caisses populaires of Alphonse Desjardins*. He extolled the rural life of farmers, which was centred on the parish church, and criticized the unwholesome atmosphere of the cities. He spoke to workers and wanted to set up a workers’ assembly where they and their employers could discuss their respective rights and interests. He took aim especially at Adélard Turgeon*, the minister of lands and forests, and at Jean Prévost*, the minister of colonization, mines, and fisheries. Turgeon challenged him to stand for election in his riding of Bellechasse to settle their differences. Bourassa agreed to do so. On 4 November Turgeon defeated him decisively by 749 votes. The Conservatives immediately proposed a tacit alliance for the next provincial election, which Bourassa entered into in return for their support in launching a newspaper that would reflect his views. He tried his chances in Saint-Hyacinthe and in Montreal, Division no.2, where his opponent was Premier Gouin. On 8 June 1908 he won narrow victories in both ridings.

Allied with the Conservative leader Joseph-Mathias Tellier and with La Vergne, Bourassa attacked Gouin (who had been elected in Portneuf) in the 1909 session. When he had the floor, the galleries were full and journalists came in droves. It was only during that first session that he truly shone. He touched on a great many subjects. Gouin always had a ready answer: it was an equal contest between the two men. Bourassa gradually lost interest in the Legislative Assembly, and in 1912 he left the provincial capital. The Nationaliste movement, which he refused to turn into a party with himself as leader, ceased to be a force in provincial politics. Meanwhile, he had influenced the government to exercise better control over speculation, to lease waterfalls on a long-term basis rather than selling them, to appoint a commission to regulate the granting of water resources, and to impose an embargo on the export of pulpwood cut on crown lands in order to have it processed in the province.

Bourassa’s priority was still to launch a daily newspaper. Since the 1908 election he had been working on this project with Asselin and others, having received the approval of Archbishop Paul Bruchési* of Montreal. Ever a pragmatist, he insisted that his financial backers, who were mainly Conservatives, give him control of 50 per cent plus one of the company’s shares, with full control of the paper and complete independence. Le Devoir, with its motto Fais ce que dois (“Do what you must”), published its first issue on 10 Jan. 1910. A daily focused on ideas and principles, with a militant voice, this moral force would be basically Catholic and nationalist. In his first editorial Bourassa indicated clearly how he would work. “We will take men and facts one by one and we will judge them in the light of our principles.” He surrounded himself with a solid and experienced team, including Asselin, Héroux, La Vergne, Georges Pelletier*, and Jules Fournier*. The signed articles they wrote appeared first in a four-page newspaper, which grew to six, eight, ten, and twelve pages, with a circulation of 12,529 in 1910 and 13,504 in 1930.

Through the various crises it experienced, Le Devoir would survive through the substantial efforts of its editor-in-chief, who had connections with businessmen such as Guillaume-Narcisse Ducharme*, president of the Life Insurance Company La Sauvegarde, of which Bourassa had been secretary-treasurer from 1903 to 1908. Until he left the newspaper of his own will on 2 Aug. 1932, Bourassa would retain control of it, although from 1918 he often turned the administration and management over to Héroux and Pelletier. From the outset, his salary was a little less than $1,820 a year, lower than that of journalists he hired. In general, his relations with his employees were friendly, but not familiar. Though poorly paid, the staff spared no effort for the cause of Le Devoir. By his rigorous thinking and his clear, direct, and concise style, Bourassa made it one of the most prestigious and influential newspapers in the province. Le Devoir was undoubtedly Bourassa’s greatest achievement, and he became the most important intellectual in Quebec. He brought to it almost in their entirety the ideas he had enunciated since entering public life. Despite some progressive points, they had one characteristic in common: their conservatism.

From the very first days of Le Devoir, Bourassa threw himself into the campaign against the creation of a Canadian navy, set out in a bill that Laurier introduced in the House of Commons on 12 Jan. 1910. On 20 January he convened a huge meeting in Montreal to denounce this non-Canadian navy, which would cost much more than anticipated and would lead to participation in Great Britain’s wars, to the abyss of militarism, and, even worse, to conscription. To Bourassa, it represented the resurgence of British imperialism. In his view, the Canadian people had to be consulted by plebiscite. In May he agreed to ally his Nationaliste movement with Frederick Debartzch Monk*, the leader of the federal Conservatives in Quebec, who, on this question, opposed both their own leader, Robert Laird Borden*, and Laurier. A coalition was born that would become the Parti Autonomiste or Conservative-Nationaliste alliance. The two leaders held many meetings in Quebec during the summer of 1910. On 10 September Bourassa’s reputation was enhanced by his reply, in the church of Notre-Dame in Montreal, to Archbishop Francis Alphonsus Bourne of Westminster, who asserted that in Canada Roman Catholicism ought to be linked to the English language. “There are only a handful of us, it is true, but we count for what we are, and we have the right to live.” There was instant elation. To put a stop to Bourassa’s progress, Laurier called a by-election in Drummond and Arthabaska, a traditionally Liberal riding. On 3 November the Liberals conceded defeat. The general feeling in the province of Quebec was that, through the candidates who ran for office, Bourassa had defeated Laurier.

In 1911 Bourassa carried on the struggle alongside Monk, even though their alliance might have been damaged by Laurier’s scheme for commercial reciprocity with the United States, which Bourassa favoured but Monk opposed. At that time, Monk and his group accepted all the fundamental principles of the Nationaliste movement. When the prime minister, irritated by the resistance to reciprocity, called an election for 21 Sept. 1911, the Parti Autonomiste was ready. Its strategy was simple: send enough independent mps to Ottawa to hold the balance of power. Bourassa formed a shocking electoral alliance with Borden, who helped him financially in his struggle in the province. Bourassa and La Vergne did not run, but they led the attacks against Laurier’s naval policy and even against Borden’s. When the votes were counted Laurier had been defeated, mainly on the issue of reciprocity. Bourassa and Monk got 17 candidates elected. The editor of Le Devoir was at the pinnacle of his glory.

With a 47-seat majority, Borden could govern the country as he wished. Bourassa recognized the limits of his electoral success. Though he refused a seat in the Borden cabinet, he agreed to the appointment of three of his Conservative allies from Quebec, including Monk. He himself would oversee these ministers and the other Conservative Nationaliste mps. Two issues would be especially close to Bourassa’s heart until 1913. The first was the extension of the boundaries of Manitoba by adding part of the District of Keewatin [see George Robson Coldwell*]. On 27 Feb. 1912 the Borden government decided to proceed without taking into account the Catholic minority in this district, which would thereby lose its separate schools. Bourassa protested and asked the Conservative Nationaliste ministers and mps to act as nationalists. All but seven supported Borden. This was the first defeat of Bourassa that involved his allies of 1911. Next, when on 5 Dec. 1912 Borden decided to give $35 million to England for the construction of three Dreadnoughts, only eight Conservative Nationaliste mps, including Monk, opposed the prime minister. Bourassa published more and more articles in Le Devoir, but since the majority of the Conservative Nationaliste mps disassociated themselves from his 1911 speeches, he broke with them. The Nationaliste movement now became the object of Laurier’s ridicule. With its Liberal majority, the Senate would block Borden’s naval bill in May 1913, but, whatever he might say, Bourassa, who wrongly claimed credit for its defeat, had lost face. He paid the price for not having played strictly by the rules of the party system and for having left his colleagues on their own by refusing to run in 1911.

Bourassa did not, however, lose his personal credibility in these years. He made many speeches, travelling to Ontario, western Canada, and the United States, where he championed, among other things, the French language as guardian of the faith and of confederation. In 1913 he outlined the basis for Canada’s foreign policy: the settlement of conflicts by international arbitration. As an intellectual, he exercised considerable moral authority. He was quick to defend the cause of the Franco-Ontarians, who in large part were deprived of their right to instruction in French by Regulation 17, which had been enacted in 1912 by their provincial government [see Sir James Pliny Whitney*]. On 21 May 1914 he set off on another fact-finding trip to Europe, where he met Winston Churchill and David Lloyd George, among others. On 1 August, as the threat of war was intensifying in Europe, he was in Strasbourg (France), a city then under German control. He managed to get back to Paris two days later, in the nick of time. On 4 August World War I broke out. By 21 August he was back home. An extremely troubled period was about to begin for him.

At the outbreak of the conflict, Canada, which was automatically at war by virtue of its status as a colony within the British empire, was bursting with enthusiasm. When the political parties agreed to help the mother country and send volunteer troops overseas, both francophones and anglophones supported these measures. Since Bourassa had condemned the decisions taken in 1899, 1910, and 1912, he had to react publicly. On 8 September, in Le Devoir, he accepted – “with reluctance,” he would later say – Canada’s involvement as a nation, to the extent of its power and by means of action of its own. In other words, he repudiated his past and tried to go along with the prevailing mood. Immediately after his editorial appeared, however, he published a series of forceful articles in which he assigned blame to both belligerents and exposed England’s hidden financial ambitions and egotism, the overzealous policies of the Canadian government, the economic risks of participation, and the excessive number of volunteers in uniform. Furthermore, he challenged the “Prussians of Ontario,” who were persecuting the French schools in that province. It was all too much for his adversaries, in both Quebec and English Canada, and for bishops such as Bruchési. This “traitor” to the nation, this troublemaker, was brewing up a storm. It was worse in 1915, when the war dragged on, requiring ever more soldiers, and when the crisis in Ontario persisted. His articles in Le Devoir, his speeches, his book Que devons-nous à l’Angleterre?: la défense nationale, la révolution impérialiste, le tribut à l’Empire, which was published in Montreal that year, all combined to stir debate. He became the public enemy of English Canadians, who urged that Le Devoir be shut down and its editor-in-chief arrested. Bourassa’s rising influence among his own people made the political and religious authorities fear the worst.

Bourassa went even further in 1916, acknowledging that he had reverted to “undiluted nationalism.” As the champion of the minority in Ontario, he made their cause that of all French speakers in North America, even putting it ahead of the struggle in Europe. He manifestly had an impact on francophones, who, subject to other influences as well, had virtually stopped enlisting. When Borden proposed conscription in May 1917, the province of Quebec was on the brink of violence. Bourassa’s prestige was at its peak; even the bishops declared their support for him. He could have taken over the province at a stroke, as Laurier and Borden feared. He was responsible enough, however, to call for resistance by constitutional means, and backed Laurier’s solution: a referendum (which he also referred to as a plebiscite). He repudiated the Union government formed by Borden in the fall and joined forces with Laurier in an effort to defeat him in the election of 17 December. Together, they swept the polls in the angry province of Quebec, but they were crushed in English Canada. In the divided country, Bourassa tended to support isolation for French Canadians, but not separation from the rest of Canada. His correspondence shows, in fact, that he opposed the separatist motion presented in the Quebec Legislative Assembly by Liberal Joseph-Napoléon Francœur in December 1917 [see Sir Lomer Gouin]. Gagged by Borden’s strengthened wartime censorship, Bourassa set aside his stinging articles in April 1918. He had earlier found time to denounce women’s suffrage, a right accorded by Borden, as well as those responsible for the deadly riots at Quebec [see Georges Demeule*]. Above all, he discussed the coming peace, “the Christian peace,” at the centre of which he placed mediation by Pope Benedict XV. More than ever, perhaps, Bourassa viewed politics through the lens of religion. This is where he stood at the end of the war, as his career was about to take another turn.

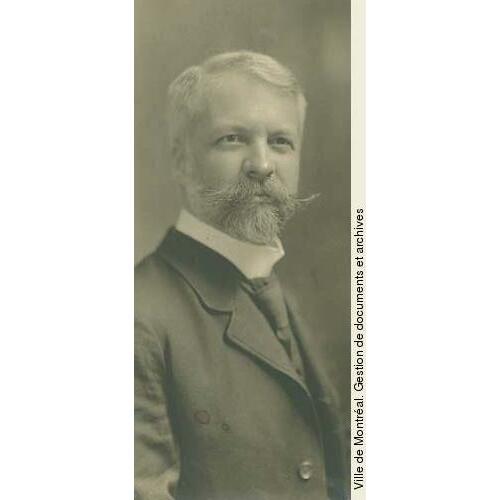

A man with a touch of mysticism, he was now 50 years old, white-haired, and worn out. He suffered a heavy blow on 26 Jan. 1919, when his wife died after a long illness. He was left with eight children, the eldest of whom was only 12 years old. The death of Laurier, the man he had both admired and despised, whose importance in his life he had always recognized, followed soon after. The former prime minister differed from him by education and in character, as well as in terms of relations with the church, the party system, a spirit of compromise, and political realism. Less brusque, Laurier was more affable, intensely disliking the clear-cut situations so dear to Bourassa. Of course, these two great humanists were similar in a number of respects as well. They had the same openness to culture, learning, and humanity in general, the same rational approach, the same attraction to classical liberalism, social conservatism, and British institutions, and finally, the same Canadian nationalism and love of their compatriots, even though from 1899 their methods of displaying these had driven them far apart. It was the end of an era. The war had also wrought havoc. Bourassa saw many dangers facing Canada: Bolshevism, socialism, feminism, secular trade unionism, strikes inspired by revolutionary forces, individual selfishness, extreme materialism, class rivalry, and the failure of parliamentary government. The Catholic social order was threatened by the desire of individuals to take the place of God. He now decided to promote a program of Catholic social action that would attack the roots of evil.

Ever the ultramontane, Bourassa put the finishing touches on his social thinking of yesteryear. From now on, the ideologist and moralist would prevail over the politician and journalist, but not completely replace them. To ensure the success of his program, he laid out a hierarchy of typically ultramontane duties. In 1921, for instance, in his important pamphlet La presse catholique et nationale, he wrote “that religion takes precedence over patriotism, that preservation of the faith and morals is more important than holding on to the language, that maintenance of national traditions, especially family virtues, outweighs the demands of higher education or the production of literary works.” On the basis of these premises, he made numerous speeches smacking of passionate homily, in Quebec and then in Ontario, Acadia, and western Canada, and wrote many articles and pamphlets. The targets of his attacks included growing urbanization and industrialism, proposals for state-funded public assistance, and trusts and monopolies. He praised agriculture, colonization, and the Catholic trade unions. He made his activities part of the promotion of the Catholic press, with the further objective of filling the empty coffers of Le Devoir.

In the same spirit, Bourassa rejected the plan that a group of intellectuals, gathered around Abbé Lionel Groulx*, the editor of the Montreal magazine L’Action française, proposed to their compatriots in 1922 as an ideal to attain: the creation of Laurentie, a country separate from Canada. Bourassa had not been consulted by Groulx, but he had referred to this idea in December 1921 and on 23 Nov. 1923 he replied in a speech that turned into another famous pamphlet, entitled Patriotisme, nationalisme, impérialisme ... and published in Montreal that year. He relied in particular on Pius XI’s Ubi arcano Dei, an encyclical written in 1922 that condemned “extreme nationalism.” Subtly connecting the separatist dream with excessive nationalism, which he again termed a threat, he proclaimed his attachment to Christian patriotism and nationalism, the only “true patriotism” and “true nationalism.” Then he analysed the separatist option. “Is this dream attainable? I do not think so. Is it desirable? I do not believe so, either from the French point of view or, even less, from the Catholic point of view, which in my opinion takes precedence over the interest of French.” He concluded: “The preservation of the faith ... is more important than the preservation of any language, than the victory of any human cause.” The master, still enjoying an aura of prestige, had dealt a hard blow to the separatist dream.

Bourassa’s project of moral regeneration had its crowning moment on 18 Nov. 1926, when he had a one-hour private audience with Pius XI. The pope’s remarks agreed in substance with the thesis of Patriotisme, nationalisme, impérialisme. In his “Mémoires,” Bourassa would describe his reaction: “I left there strengthened, comforted, enlightened for the rest of my days.” He believed from then on that he had been entrusted by Pius XI with the mission of making his ideas better known and accepted in Canada.

On his return from Europe, Bourassa plunged wholeheartedly into political debates. In 1925 he ran as an independent in the federal riding of Labelle, where he was elected on 29 October by 2,079 votes, and then again in the general election of 14 Sept. 1926 by 6,322. In parliament he aroused curiosity because of his reputation. He carried out his parliamentary duties, usually alongside the Liberals, who had been returned to power under William Lyon Mackenzie King*. Rather isolated among a cohort of parliamentarians whom he did not know, he drew closer to former opponents such as Rodolphe Lemieux*, and learned to appreciate other members such as the socialist James Shaver Woodsworth*. Increasingly taking on the role of conscience of the house, he scorned patronage to concentrate on the big political issues, both national and international. Until 1930 he discussed, among other concerns, the plans for old-age pensions, to which he was opposed, government budgets, the cause of the French language and bilingualism in the country, western Canada’s natural resources, and the law on divorce. He also touched on such subjects as world peace and Canada’s relationship with the British empire. He welcomed, with some reservations, the results of the 1926 Imperial Conference, which recognized Great Britain and the dominions as autonomous communities, equal in law, in no way subordinate one to another, and freely associated as members of the British Commonwealth of Nations. For him, it was simply a question of recognizing an accomplished fact. He attacked, among other things, the principle of solidarity in imperial obligations, which, if maintained, would be an obstacle to attainment of national independence. In the general election of 28 July 1930 he was returned by acclamation in Labelle, while the Conservative Richard Bedford Bennett* replaced King as prime minister.

During these years, Bourassa was active outside the house as well. He wrote articles on current topics, both national and international, and made several stirring speeches, in Montreal in particular, to mark the 60th anniversary of confederation, and, soon after, in the course of a patriotic teaching tour of western Canada. His most important stand had to do with the agitation that involved the newspaper La Sentinelle (Woonsocket, R.I.). Some Franco-Americans, along with their paper, were at odds with the Irish bishop of Providence, William Hickey, who wanted to raise funds among the Catholics of his diocese to build English-language Catholic secondary schools. This affair, which was followed closely by the nationalist elite, the clergy, and Quebec francophones, went all the way to the pope. In 1928 Pius XI ruled in favour of Bishop Hickey, condemned La Sentinelle, and excommunicated the rebels. They did not lay down their arms, however, and even spoke of schism in 1929. It was at this point that Bourassa, a staunch defender of minorities who had long been interested in the French Canadians who had emigrated to the United States, intervened. Beginning on 15 Jan. 1929 he published five articles that were devastating for the cause of La Sentinelle. He called for submission, explaining that the essential authority of the church had to be preserved and the subordination of Catholicism to nationalism prevented. The effect was far-reaching. The crisis was immediately resolved in the United States, but in Quebec there was an outpouring of reaction. Among the most disappointed were the nationalists of the Ligue d’Action Canadienne-Française, who no longer recognized their mentor. With Groulx at the head, they refused to accept this separation of nationalism and Catholicism so dear to Bourassa. The master was in the process of destroying his past. Bourassa replied to them in a speech on 3 Feb. 1930: “as to the root of the national and religious problem, I hold the same position that I did 10, 20, or 30 years ago.” He was right. “When conscience calls,” he added, “[the goad of public opinion] must speak out.” Pure Bourassa.

During the years from 1930 to 1935, Bourassa kept himself, for the most part, above the fray in the House of Commons. He approached men and things from the lofty height of his principles, often glorifying the pope and commenting on the encyclicals. On 30 June 1931, for example, he welcomed the Statute of Westminster, which granted partial independence to Canada, but he regretted that the country had not been completely separated from Great Britain. In 1934 he attacked anti-Semitism and racism, which he had already repudiated, in particular by his support in 1930 for the principle of establishing a system of Jewish schools in Montreal. In 1934 he also spoke about the depression; his economic-religious reflections, containing little that was original, repeated many of his dogmas from the past. In 1935 he had kind words for Bennett’s so-called New Deal and spoke in favour of the cause of preserving world peace.

Bourassa carried on these battles in Le Devoir, and dealt with other topics. In 1931 he analysed the provincial law on workplace accidents, describing it as “A well-intentioned ... monster” of state control in Quebec, while nevertheless supporting its basic features. He also touched on Germany’s positive role in blocking the expansion of Bolshevism. In Le Devoir and elsewhere, however, Bourassa’s remarks occasionally offended the paper’s readers. Besides nationalists of every stripe, other groups, such as members of the clergy, were also affected. On 4 March 1932, in an address entitled “Honnêtes ou canailles?,” printed in Le Devoir three days later, Bourassa accused the latter of enriching themselves unduly from the church’s property. Many of Le Devoir’s natural supporters were offended and cancelled their subscriptions. With the depression increasing the newspaper’s financial difficulties, it was on the verge of bankruptcy. The management of the daily and its board of directors were under great pressure. Aware of all these realities, Bourassa let slip the word “resignation” in the spring of 1932. In May the board took him at his word, and his resignation came into effect on 2 August. The information, given in a single news item, caused a sensation. Many people wondered what was behind the affair, while some mistakenly referred to a dismissal. Morose and extremely upset, Bourassa hid away in the commons and considered retiring from public life. One page of his life, probably the most important of all, had just been turned. On 7 Dec. 1933, Abbé Groulx, in a letter to Armand La Vergne, gave a general idea of the anger then being directed at Bourassa by French Canadian nationalists: “How sad some lives [are] at the end!... Could it be purely a matter of intellectual evolution this time? Might there not also be an element of cerebral evolution?... To sum up: ... no one here gives a thought to him any more. And that is really the tragic side of this man’s destiny, that while still alive, he is treated as dead.”

But Bourassa would still make his voice heard in Montreal and again arouse the fury of Groulx’s nationalists. In April and May of 1935 he gave three speeches on nationalism. At the outset he asked the question, “Is nationalism a sin?” While he began by legitimizing Canadian nationalism, the kind that reacted against imperialism and colonialism and that protected the rights of minorities, he confessed to having committed five sins, the greatest of which was certainly the one of using words that could have made people think that the French language took precedence over the Catholic faith. Then he declared his “disagreement with the neo-nationalism introduced by L’Action Française of Montreal, continued and intensified by Jeune-Canada,” and he ridiculed the separatists. In his opinion, they showed a “deviation from the sense of nationality and the sense of religion” and he described them as “fomenters of race hatred.” He went on to deplore religious nationalism, which was “the antithesis of Catholicism,” and was too much in evidence in Canada. He denounced the anti-Semitism that was rife in Quebec and elsewhere. These speeches, though demonstrating the continuity in Bourassa’s thinking, aroused Groulx’s anger, and he replied immediately in the May issue of L’Action nationale (Montréal). It was an all-out, savage attack on the former mentor “who has destroyed the ideal of a generation” and who “is no longer a master.” These blunt and unfair comments show the unbridgeable gulf between the two men. Bourassa took note of them and said nothing. In the fall he agreed to seek a new term as an mp. Maurice Lalonde, a young Liberal lawyer, decided to run against him and on the evening of 14 Oct. 1935 Lalonde received a majority of 1,869. “Apart from the very slight injury to my self-esteem,” Bourassa wrote to his daughter Anne, “I feel relieved of a great burden and even delighted.”

At the age of 67, Bourassa began his long retirement. Until 1938, although he appeared less often on the public scene, he spoke occasionally on Canadian affairs and reiterated many of his ideas, arousing anger among the French Canadian nationalists. In fact, he was now looking mainly towards Europe, sunk in anxiety about another world war. He even travelled there in 1936 and again in 1938. Above all, Bourassa feared communist Russia because it threatened God, the family, and property. He had no more love for Germany and Nazism, which extolled “the worship of race” and hatred of the Jews, but he admitted that Germany, an unstable nation humiliated by the Treaty of Versailles, “is the only force capable of putting order in the Slavic chaos.” He hoped for a Franco-German entente that would involve the Italy of Benito Mussolini, whom he had met for a second time in 1936. Finally, he called on the powers to put their trust in the wisdom of the pope.

Then there was complete silence for nearly three years. Increasingly religious, Bourassa lived a life of serene solitude. A keen conversationalist in private life, he occasionally received visitors with whom he discussed Canadian and European affairs. His health was still good. He took long walks, saying his rosary as he went; for relaxation he played chess or cards, his plaster pipe in his mouth. And he read voraciously until, much to his regret, problems with his eyes forced him to stop. In May 1941 he agreed to give a speech in Montreal to support a religious endeavour. Now nearly 73 years old, he was back in the public eye. This marked the beginning of his official pronouncements about the war, which was dragging on far too long. Until 1944, Bourassa would return to the object and even the arguments of his nationalist battles of bygone days. While he denounced the Axis, dominated by Nazi Germany, he showed sympathy for Marshal Philippe Pétain’s France and Christian Italy. He frankly expressed the desire for Canada’s withdrawal from the war, which ought to end in a negotiated settlement. Above all, he called for the establishment of a Christian social order. It was in this context that a rapprochement with the French Canadian nationalists was reached at the end of 1941. The reunion, which was initiated by the nationalists, was marked by mutual respect. They were opposed, as he was, to imperialism and conscription, which they increasingly feared would be introduced by Prime Minister King. In February 1942 they founded the Ligue pour la Défense du Canada, and then on 8 September a political party, the Bloc Populaire Canadien, rekindling the flame of Canadian nationalism of their erstwhile leader. Although not a member of either of these two groups, Bourassa worked with them and supported their objectives. Opposed, among other things, to the plebiscite of 27 April 1942, which was designed to release the King government from its promise not to impose conscription, he took part in many of their political and electoral meetings until 1944.

During the months from 13 Oct. 1943 to 15 March 1944, on the advice of a number of nationalists that included Jean Drapeau* and André Laurendeau*, Bourassa recounted his “Mémoires” at Plateau Hall in Montreal. In the course of his ten talks, one of which was recorded and all of which drew a crowd of faithful listeners, Bourassa reviewed his life, displaying his prodigious memory and youthful expressiveness. He sought to show the unity of his thought and action, which in spite of some complicated detours drew their inspiration from the twin family backgrounds of Papineaus and Bourassas. Despite lapses in recall, omissions, self-congratulatory touches, and a mingling of personal memories and digressions, which weakened his argument, the “Mémoires” are still a remarkable source of information.

In the fall of 1944, Bourassa, who was now 76, had a heart attack which made his retirement complete. Although he recovered, he was still frail and was frequently unwell. He had, however, meanwhile regained enough of his sight to be able to read. He prepared for death with a daily ritual worthy of a monk: reading the daily mass, the proper in the breviary, the lives of the saints, and L’imitation de Jésus-Christ, reciting his rosary, making the Stations of the Cross, engaging in family prayers. To this he added the small pleasures derived from his pipe, his cigars, games with his family, visits from friends, and perusal of Le Devoir. On the day before his 84th birthday, Bourassa got up feeling better than usual. Suddenly, he was struck by a sharp pain in his heart. At his request, his son François, a Jesuit, gave him absolution. Surrounded by his family and conscious to the end, Bourassa breathed his last on 31 Aug. 1952.

From that day, the man and his work belonged to history. Neither would be easy to evaluate. Journalist André Laurendeau even acknowledged in 1954: “A man like Bourassa cannot be captured by a formula: he always in one way or another transcends [it].” What then is Henri Bourassa’s legacy to posterity? No doubt the memory, in the minds of Canadians, of a prestigious name constantly recalled by the various streets, boulevards, electoral constituencies, regional school boards, schools, buildings, and a subway station named in his honour. The books, theses, and articles devoted to him, both laudatory and critical, have become accounts of his era. Papineau’s grandson remains a presence symbolizing a notable contribution to the building of the country. Bourassa was not a great politician, however. Since both his character and his principles made him incapable of coming to terms with power in all its forms, he never learned to move easily within its restrictive framework, and suffered the consequences. His true path was found in militant Catholic journalism. He was first and foremost a committed intellectual, who was endowed with incomparable charisma and culture. Between 1899 and 1920 especially, he led some of his most enlightened compatriots to turn their minds to public affairs and to become involved, through thought and action, in the debates about the future of their society and their nation. The nationalist revival that Quebec experienced at the beginning of the 20th century was of his making.

Bourassa was also a trailblazer. In 1954 the magazine L’Action nationale wrote: “today, the greatest part of the political program he supported, almost in the face of complete opposition, has become that of most Canadians and serves to ensure the prestige of our major parties.” This was the case with his staunch defence of Canadian autonomy and independence, as well as respect for minorities and the bicultural character of the country. In a sense, he was the first to work at establishing, in a considered and organized way, a political philosophy capable of clarifying Canadian problems at the beginning of the 20th century. He gave his compatriots a more precise understanding of Canada’s relations with the empire and the relationships between the majority and the minority. Moreover, he was the instigator, at least in Quebec, of sustained reflection on peace and international issues. It is not surprising that he is known as the father of independent political thought in French Canada. His social and economic views, which were influenced by his ultramontanism and his own era, were not, however, either progressive or original, despite some reformist elements. They exude a sometimes anachronistic and rather narrow view of things and of people, especially of women, whose emancipation he helped delay. As a member of a petty-bourgeois elite, he had been one of its most eminent spokesmen: the vigour and logic of his pronouncements surpassed those of his contemporaries.

A man of duty, sometimes perceived as the conscience of his people, Henri Bourassa was above all a great Catholic obedient to the directives of the pope. He formed an attachment to these instructions early in his career, and they guided his thoughts and actions for the rest of his life. Many supporters, even among his most faithful nationalist disciples, were alienated by his attitude, which was not really understood. In his Mémoires, Abbé Groulx recalled the damage Bourassa had done to the cause of French Canadian nationalism. Once this mood had been set, the Quebec nationalist generation of the 1960s also turned away from Bourassa’s ideas, which they considered too frankly Canadian. At the same time, however, other Quebecers, such as Pierre Elliott Trudeau*, promoted some essential aspects of his thought. The majority of Bourassa’s English Canadian Protestant compatriots were displeased with his thinking as a whole. They mistakenly accused him of destroying Canadian unity, creating racial division, and being a troublemaker. There was certainly nothing about the vigorous expression of his intransigent Catholicism that could attract them to the kind of nationalism he was defending. But was Bourassa entirely in the wrong? English Canadians of his day, and many of their historians since then, have not listened to him carefully enough and have not tried to grasp fully the sense of his struggles. Had they done so, they would have discovered in Bourassa what a number of better-informed English Canadian historians now realize: that he was a proud supporter of the spirit and letter of the Canadian constitution, a Canadian nationalist devoted to Canada, his only country. In sum, here was a courageous thinker who, in many respects, can still inspire Canadians.

The author would like to thank Mme Michèle Brassard for doing indispensable research for him.

The essential sources for this biography are the correspondence and the writings of Henri Bourassa. The principal Bourassa archives are held at Library and Arch. Canada (Ottawa), R8069-0-5 (Henri Bourassa fonds) and at the Centre de Recherche Lionel-Groulx (Outremont, Qué.), P65 (fonds Famille Bourassa). Mme Anne Bourassa’s patience and attention to detail in meticulously preserving her father’s memory must be acknowledged. Many discussions were held with her about her father. Other archival collections, in particular those of politicians and journalists, shed light on many aspects of Bourassa’s career. They include, at Library and Arch. Canada, those of Sir Wilfrid Laurier (R10811-0-X), the Famille Armand Lavergne (R6172-0-1), and Frederick Debartzch Monk (MG 27, II, D10A). Also useful is the collection of Olivar Asselin’s papers at the Ville de Montréal, Section des archives (BM55). The author holds several unpublished pieces of correspondence in which Henri Bourassa is a central figure. Bourassa’s baptismal certificate can be found at Bibliothèque et Arch. nationales du Québec, Centre d’archives de Montréal, CE601-S51, 2 sept. 1868.

The titles of Henri Bourassa’s numerous books and pamphlets can be found in André Bergevin et al., Henri Bourassa: biographie, index des écrits, index de la correspondance publique, 1895–1924 (Montréal, 1966). They have all been consulted and some have been quoted in the biography. These publications are indispensable for identifying the evolution of this committed intellectual’s thinking. The same is true for Bourassa’s work as a journalist, which is to be found mainly in the newspapers he edited or founded: L’Interprète, Le Ralliement and Le Devoir, which were all examined. His articles in Le Devoir, from 1910 to 1932, have been copied on microfilm. Other newspapers of the day, particularly those to which Bourassa’s friends and political opponents in Quebec and elsewhere in Canada contributed, afforded a better understanding of the reactions Bourassa aroused. By way of example, the Quebec City newspapers La Vérité and Le Soleil, as well as Le Canada in Montreal, were useful. Two sources assisted in evaluating the role played by Bourassa as an mp and as an mla: Can., House of Commons, Debates, 1896–1907, 1926–35 and Qué., Assemblée législative, Débats, 1909–12. To all these works must be added the memoirs of prominent figures of the time, the most relevant being those of Bourassa himself, held at the Centre de recherche Lionel-Groulx, P65/B9, 2-11, Armand La Vergne, published as Trente ans de vie nationale (Montréal, 1934), and Canon Lionel Groulx, entitled Mes mémoires (4v., Montréal, 1970–74).

Specialized studies, doctoral dissertations, ma theses, and scholarly articles have made it possible to examine in greater depth some aspects of the nationalist leader’s career and thought. Although many of these works are becoming dated, their contribution should be recognized. Among them, the biography by historian Robert Rumilly, Henri Bourassa: la vie publique d’un grand Canadien (Montréal, 1953), deserves mention. A sweeping chronicle developed without footnotes, it covers Bourassa’s entire life and includes a great deal of information of various kinds. Historian Joseph Levitt has written several key works, including Henri Bourassa on imperialism and biculturalism, 1900–1918 (Toronto, 1970), Henri Bourassa and the golden calf: the social program of the nationalists of Quebec, 1900–1914 (2nd ed., Ottawa, 1972), and Henri Bourassa: Catholic critic (Ottawa, 1976). So too has historian René Durocher, who produced two solid articles: “Henri Bourassa, les évêques et la guerre de 1914–1918,” Canadian Hist. Assoc., Hist. Papers (Ottawa), 1971: 248–75, and “Un journaliste catholique au XXe siècle: Henri Bourassa,” in Pierre Hurtubise et al., Le laïc dans l’Église canadienne-française de 1830 à nos jours (Montréal, 1972): 185–213.

Mention should also be made of the insightful article by journalist André Laurendeau, “Le nationalisme de Bourassa,” L’Action nationale (Montréal), 43 (1954): 9–56, and the works of historian Susan Mann: Action française: French Canadian nationalism in the twenties (Toronto, 1975); “Variations on a nationalist theme: Henri Bourassa and Abbé Groulx in the 1920’s,” Canadian Hist. Assoc., Hist. Papers, 1970: 109–19; and “Henri Bourassa et la question des femmes,” in Marie Lavigne and Yolande Pinard, Les femmes dans la société québécoise: aspects historiques (Montréal, 1977): 109–24. To these must be added the volume Hommage à Henri Bourassa (Montréal, [1952?]), reprinted from a souvenir issue published in Le Devoir, 25 nov. 1952, which contains many tributes by friends, and the essay by historian Ramsay Cook, Canada and the French-Canadian question (Toronto, 1966). Comprehensive works on Canadian history have also proved valuable sources. The best of these with regard to Bourassa and his time remains that of historians R. C. Brown and Ramsay Cook, Canada, 1896–1921: a nation transformed (Toronto, 1974). On Le Devoir, the following can be consulted: Pierre Dandurand, “Analyse de l’idéologie d’un journal nationaliste canadien-français, Le Devoir , 1911–1956” (mémoire de ma, Univ. de Montréal, 1961); “Le Devoir”: un journal indépendant (1910–1995), edited by Robert Comeau and Luc Desrochers (Sainte-Foy [Qué.], 1996); “Le Devoir”: reflet du Québec au 20e siècle, edited by Robert Lahaise (LaSalle [Montréal], 1994); P. P. Gingras, “Le Devoir” (Montréal, 1985); and Pierre Anctil, “Le Devoir”, les Juifs et l’Immigration: de Bourassa à Laurendeau (Québec, 1988). A number of obituary articles on Bourassa appeared in Le Devoir of 2 Sept. 1952.

Among recent publications mention should be made of the noteworthy work by Hélène Pelletier-Baillargeon, Olivar Asselin et son temps (2v. to date, [Montréal], 1996– ), as well as those by Sylvie Lacombe, La rencontre de deux peuples élus: comparaison des ambitions nationale et impériale au Canada entre 1896 et 1920 (Québec, 2002), and Yvan Lamonde, Histoire sociale des idées au Québec (2v. to date, Saint-Laurent, Qué., 2000– ), 2. Finally, any work devoted to Bourassa must take into account the biographies of Canadian politicians and intellectuals who may have had an influence on his career. These have all been examined, as was the body of studies dealing with the themes and subjects dominating Canadian life from 1868 to 1952.

Cite This Article

RÉAL BÉLANGER, “BOURASSA, HENRI (baptized Joseph-Henry-Napoléon),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 18, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 10, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bourassa_henri_18E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bourassa_henri_18E.html |

| Author of Article: | RÉAL BÉLANGER |

| Title of Article: | BOURASSA, HENRI (baptized Joseph-Henry-Napoléon) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 18 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 2009 |

| Access Date: | April 10, 2025 |