Source: Link

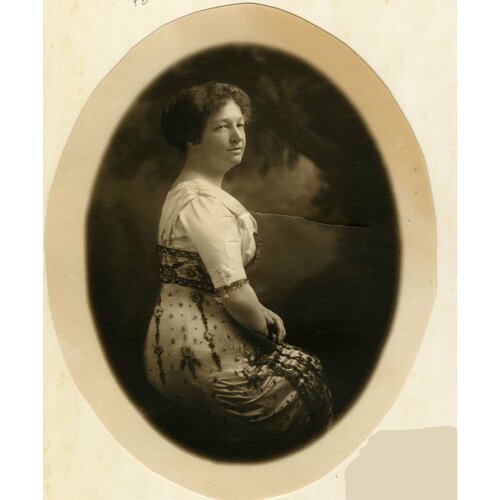

LACOSTE, MARIE (baptized Marie-Thaïs-Élodie-Coralie) (Gérin-Lajoie), feminist, social reformer, lecturer, educator, and author; b. 19 Oct. 1867 in the parish of Notre-Dame, Montreal, daughter of Alexandre Lacoste*, a lawyer, and Marie-Louise Globensky; m. 11 Jan. 1887 Henri Gérin-Lajoie in the parish of Saint-Jacques, Montreal, and they had four children; d. 1 Nov. 1945 in Montreal.

Marie Lacoste was born at a time when French Canadian life was beginning to change drastically as a result of the Industrial Revolution. In growing numbers, men and women were heading to the factories and workshops of Montreal. Far from the working-class suburbs of the city, she grew up in a house in a fine neighbourhood, where she lived with her parents and many brothers and sisters. Among the latter, Justine and Thaïs were to become active social reformers, as she would. Accompanying her mother in her charitable activities, she early on became acutely aware of the problems of urban poverty and, above all, of the fact that women did not have the power to take charge of their own destinies.

At the age of nine Marie was placed in the convent in Hochelaga, run by the Sisters of the Holy Names of Jesus and Mary. Spontaneous and frank, she was repelled by the austerity and coldness of life there, and by the required obedience to arbitrary rules. Subsequently, encouraged by her father’s promise to let her use his library as she pleased, with his guidance, upon leaving the convent, she completed her secondary education with honours in 1883. At home the young girl started studying on her own. Intelligent and eager to learn, she began to tackle the laws of physics and rudiments of chemistry, and acquainted herself with classical authors.

Aware of the demanding work of household servants and surprised to see that married women in her circle sometimes seemed to be victims of their neglectful spouses, Marie became conscious of the inferior social position of women and was indignant that they were confined to the domestic sphere or to badly paid, unrewarding jobs. Her sense of revolt was fuelled by her personal sacrifice, which she saw as unjustifiable: she would have loved to pursue her education, but all Quebec’s Roman Catholic francophone university faculties at that time were closed to women.

Anxious to learn more about what seemed to her a terrible anomaly, Marie set about studying the history of societies and of women as well as law. It was during this time that she formed several convictions that were to guide her all her life. Among them was her belief that civil law was unjust to women, mainly with regard to changes in their civil status after marriage: they then came under the guardianship of their husbands and became incompetents from a legal standpoint. Without the formal approval of her spouse, a woman had no power of consent.

The husband’s authority in the family and in civil society, which was inscribed in law, made the wife into a powerless dependant and even, in certain cases, a victim of abuse. Taking a stance that was opposed to the specious theories about the physical and intellectual inferiority of the members of the so-called weaker sex, Marie believed that such notions were a monstrous error that must be put right as soon as possible. Yet the inferiority of women was also part of the expressed ideas and practice of religion, and Marie was an ardent believer. She wondered how she could overcome this contradiction without being called a heretic. She found the answer by steeping herself in the story of the life of Jesus, who came to save all the souls on earth, because only souls - and not inferior and superior beings – appear before God.

In 1884 she met the young lawyer Henri Gérin-Lajoie, a son of the man of letters Antoine Gérin-Lajoie* and Joséphine-Henriette Parent, a daughter of the moderate Patriote Étienne Parent*. She developed a high regard for him and realized that the liberal milieu to which he belonged would be of service to the goal she had set herself: working to elevate the status of women. Their marriage was celebrated on 11 Jan. 1887 and subsequently she gave birth to Marie*, Henri, Alexandre, and Léon. While devoting several hours a day to her reading and charity work, thanks to the presence of servants, she saw to the smooth running of her household and to the religious, moral, and academic education of her children, who could read, write, and count before they started school.

The publication of the papal encyclical Rerum novarum in 1891, which reconciled Catholicism with certain social values such as the right to strike, as well as the rise of Christian feminism in France, allowed Marie Gérin-Lajoie to combine her desire for reform with her personal faith. She had already realized that the Catholic religion was not immutable and that its precepts had evolved over the centuries in a manner much more human than divine. Her contact with Christian feminists, notably Marie Maugeret, who wanted to promote women’s equality while denouncing the libertarian tendencies of the early European and American feminists, gave a definitive direction and meaning to her commitment. Marie finally could openly declare herself a feminist and act accordingly.

In a society that was as Christian in its institutions and morality as the one in which she lived, the feminist movement, to be accepted, had to ally itself with the social-reform movement in which women were already very engaged. This movement, which came within the Christian tradition of charity, endeavoured to denounce the sometimes-deplorable living conditions of the working class and it had been well received by the male elites for several decades. There was a natural shift towards feminist action since women of the labouring classes were generally the worst off of all.

Brought together within charitable organizations or literary societies, female militants, who were mainly anglophone, began to take public action to supply solutions for the social problems of their day. In 1893 the National Council of Women of Canada and its Montreal chapter were founded. Marie joined in, participating for the first time in an organized movement that saw the common situation of women as one of the most glaring contemporary problems. She already believed firmly that women had to unite in order to improve their collective and individual lot.

In a province dominated by Catholicism and where speaking in public was a daring act for a woman, a francophone Catholic woman’s membership in the NCWC, an anglophone and non-denominational organization, was neither obvious nor simple. Within the council Marie met avant-garde French Canadian women: Marguerite Thibaudeau [Lamothe*], a woman committed to numerous causes, as well as the journalists Joséphine Dandurand [Marchand*] and Robertine Barry*. The latter two would publish articles by Marie in their respective periodicals in Montreal, Le Coin du feu and Le Journal de Françoise. In 1900 she became a member of the executive committee of the NCWC’s Montreal chapter and led several awareness-raising campaigns focused on increasing the categories of women eligible to vote in Montreal municipal elections and defending the rights of female workers.

Increasingly assertive, Marie got involved in various controversies regarding, among other things, the right to higher education and the right to have the job of one’s choice. In a book published by the NCWC in 1900, Women of Canada: their life and work; compiled … for distribution at the Paris International Exhibition, 1900, she again took up one of her favourite subjects in a chapter entitled “Legal status of women in the province of Quebec.” Her interest in law, combined with her desire to combat women’s ignorance, which was the source of their inferior status, led to an ambitious project: writing a book about law for the general public. Thus in 1902 she published A treatise on everyday law (Montreal), which dealt with the legislation governing the private life of women. With this tool, she attempted to have law introduced into school curricula as a subject. In Montreal the convent in Hochelaga, the College du Mont-Saint-Louis, and the Académie Sainte-Marie, among others, welcomed her as an instructor or guest lecturer, as did a few anglophone secondary schools and the McGill Normal School. Her reputation as an educator grew and she was invited to address a number of women’s associations.

Marie was resolved to remedy the deficiencies in the teaching of girls. She was also determined that her daughter, Marie, would be able to go to university. Yet no francophone establishment in Quebec at the time awarded females the diploma necessary for entry into higher education. In 1906 she helped set up the Écoles Ménagères Provinciales, of which she was a founding-committee member [see Jeanne Anctil*]. Subsequently, owing to her discreet pressure on Archbishop Paul Bruchési* of Montreal, and with the help of Mother Sainte-Anne-Marie [Bengle*], a nun in the Congregation of Notre-Dame whom she held in high esteem, Marie Gérin-Lajoie would be able to attend the opening of the École d’Enseignement Supérieur pour les Jeunes Filles in 1908. Thus young Marie would become the first French Canadian woman to obtain a baccalauréat ès arts.

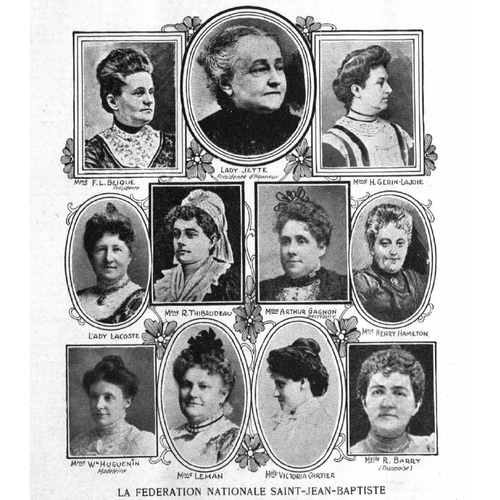

Since 1903 Marie had been considering the creation of an alliance of women’s benevolent groups like the NCWC, but one that would be francophone and Catholic. A woman of action and an unparalleled organizer, she believed that this approach was the only way for women’s charitable involvement to become truly effective and help eradicate certain social ills at their source. As a member of the women’s chapter of the Association Saint-Jean-Baptiste de Montréal since its founding in 1902, she persuaded its president, Caroline Béïque [Dessaulles], to turn the chapter into such an alliance. Thus was born the Fédération Nationale Saint-Jean-Baptiste in 1907. Caroline retained the presidency of the new organization, while Marie became secretary, a position she would hold until 1913. Archbishop Bruchési let himself be convinced that the new social Catholicism, to which he was receptive, was not dangerous to the social order; his moral authority silenced the sarcasm and criticism that arose from all quarters, especially when Marie announced her firm intention to bring about the establishment of professional associations for women. Backed by women sympathetic to the cause, including the journalist Anne-Marie Gleason [Huguenin] and the patroness Aglaé Rottot, she succeeded in setting up, in 1907 and 1908, a few of these quasi-union associations, in particular among female factory workers.

The FNSJB brought together several religious communities, among them the Sisters of Charity of Providence and parish groups as well as various women’s organizations, such as Mlle E. Viger’s academy and the Écoles Ménagères Provinciales; in all, there were 22 affiliated societies. The delegates met at annual general assemblies, celebrations, and conferences. The executive board oversaw various committees that drew public attention to several important causes. Marie was herself a member of the committees on temperance, celebrations, relief funds, and the press. The FNSJB focused first on combatting women’s ignorance, her main concern. Members of professional and parish associations were offered ever more numerous and varied lectures and classes, from sewing to law, as well as membership in study circles. Conferences greatly aided efforts to spread information and amalgamate forces. Representatives of affiliated organizations put forward, in effect, sociological surveys on both the cause they were promoting and the social fate awaiting certain kinds of women. In 1909, for example, the Sisters of Miséricorde presented a well-documented work on ways of preventing prostitution. These conferences not only allowed women to speak out at last in public and bring to light the real lives of French Canadian women but also to determine the direction of future actions.

The second cause that the FNSJB defended throughout Marie’s tenure as president, from 1913 to 1933, was the improvement of the collective lot of women. For this purpose, at the outset of her first term, she was instrumental in founding its organ, La Bonne Parole, which would be published in Montreal until 1958. All the important causes that the federation became involved in would be explained and defended in its pages. Moreover, she united the creative energies of the FNSJB volunteers in campaigns focused on making elites aware of the injustices to women created by certain laws and on getting the necessary revisions. For example, she fought for a change in the rights of inheritance, which was presented by the legislative councillor and notary Narcisse Pérodeau* and passed in 1915 by the legislative assembly. Under her presidency, the FNSJB became distinctly more militant, taking up causes such as the defence of women whose right to work was contested, a campaign to amend the Civil Code, the extension of the franchise, and the admission of women into the liberal professions and to positions of responsibility in the world of education.

In 1918 the federal government granted all women the right to vote [see Sir Robert Laird Borden*]; three years later, for the first time, Canadian women would be called to the polls. Understanding the importance of the moment, Marie organized various events to raise awareness, such as a “civics course” for women at the Université de Montréal, where lecturers outlined the major principles of public action and gave practical explanations about the vote. This huge effort to inform, which also included a press campaign, produced concrete results: a great many women cast ballots without incident.

The struggle for the right to vote in the province of Quebec took off in earnest at the end of 1921. With the president of the Montreal chapter of the NCWC, Anna Marks Lyman, Marie established the Provincial Franchise Committee, a central body coordinating the efforts of several militant women’s associations, and of which the two women became co-presidents. Idola Saint-Jean, Thérèse Casgrain [Forget*], and Carrie Matilda Derick were among the 32 women present at the founding meeting. The first joint action involved introducing a bill in Quebec City in the winter of 1922 through the intervention of Henry Miles, mp for the riding of Montréal-Saint-Laurent. Although Marie had long been aware that the province’s bishops were hostile towards women’s suffrage, she was surprised at the strength of the anti-suffragist media campaign. Certain bishops used all their power to persuade their flock that granting women the right to vote was contrary to Catholic doctrine. Fortunately, Mgr Georges Gauthier*, recently appointed apostolic administrator owing to the illness of Archbishop Bruchési, left her at liberty to take part in the struggle for the franchise as president of the FNSJB.

The bill was introduced but did not get past first reading. The media build-up surrounding the presence of a feminist delegation in Quebec City nevertheless served the cause. Marie was convinced that she had to go to Rome to seek support. Pope Pius XI agreed with extending the rights of women, on condition that women’s associations, closely supervised by the church, devote themselves to improving social life, the supposedly natural expansion of women’s maternal role. She took advantage of the conference of the International Union of Catholic Women’s Leagues, which was held in Rome in May 1922, to try and obtain clear direction. But Henri Bourassa* was on the alert. Vehemently opposed to women’s suffrage, this journalist and polemicist had privileged access to the Vatican, notably through Cardinal Rafael Merry del Val, papal delegate to the conference and chairman of the sessions. Marie believed that it was Bourassa who, by influence peddling, succeeded in having added to the resolutions adopted at the conference a clause that obliged women to receive the approval of their episcopate prior to obtaining the right to vote. In Quebec such approval was impossible at the time.

Marie resigned as president of the Provincial Franchise Committee at the end of 1922. She judged it wiser to associate the FNSJB with an initiative that was less controversial but just as important in her eyes: the civic education of women. Thus, the federation sponsored a series of classes at the Université de Montréal. The federal elections held in quick succession in 1925 and 1926 led her to believe that once more the time had come to throw the weight of the FNSJB, through the Provincial Franchise Committee, behind the struggle to obtain the right to vote municipally and provincially. She sought the approval of Mgr Gauthier. He prevaricated, then refused, and shortly afterwards stated publicly that he was opposed to women’s suffrage. In 1929 Marie therefore retired permanently from the committee, of which she had remained until then a member as president of the FNSJB.

Since 1925 the FNSJB had owned the building it occupied, and its secretarial offices were run by the Institut des Sœurs de Notre-Dame du Bon-Conseil, founded by Marie’s daughter, who had become a nun. At the beginning of the 1930s Marie devoted a great deal of energy to Civil Code reform. For decades she had been proposing, on every platform, various measures to moderate, with respect to women, the terms of the matrimonial regime known as community of property. She took advantage of the Commission des Droits Civils de la Femme, set up in 1929 by the government of Louis-Alexandre Taschereau* and chaired by the judge Charles-Édouard Dorion [see Joseph Sirois], to present her suggestions. Though she did not demand the abolition of legal incapacity, which she knew would be too bold, she urged the commissioners to ensure that a married woman’s salary would become the sole property of the person who earned it. This change in the category of a wife’s reserved property was to form one of the commission’s recommendations. The legislative amendments then put into force were for the most part suggested by Marie, who had promoted them in her work and publications, such as her articles in La Bonne Parole.

In May 1933, after the 25th-anniversary celebrations of the FNSJB, Marie left the office of president. She was 65 years old. She continued to work on various committees until 1936, the year that her husband, who had been struck by a car, died following the accident. After this event her intellectual abilities seemed to deteriorate rapidly. She settled into a small apartment at the Institut des Sœurs de Notre-Dame du Bon-Conseil. By the time the franchise was finally given to women in the province of Quebec in 1940, she had lost all touch with reality. She died on 1 Nov. 1945.

Marie Gérin-Lajoie did not wait for the achievement of the right to vote before becoming publicly involved and trying to correct what she considered men’s abuses of power against women or those who were badly off. Endowed with a deep sense of social justice and fairness, she devoted her talents to various causes directed at furthering women’s independence by their taking their own destinies into their hands. Her favoured causes were the encouragement of every kind of education and real participation in collective decision making, notably through the choice of parliamentary representatives. At a time when, in the province of Quebec, francophone feminists had no means whatsoever of exerting organized pressure, she set up the FNSJB. She not only made a forceful contribution to changing attitudes but also opened the way for the dramatic rise of Quebec’s feminist movement during the Quiet Revolution.

An exhaustive bibliography appears in the author’s book, Marie Gérin-Lajoie, conquérante de la liberté (Montréal, 2005).

Bibliothèque et Arch. Nationales du Québec, Centre d’arch. de Montréal, CE601-S33, 11 janv. 1887; CE601-S51, 20 oct. 1867; P578. Instit. Notre-Dame du Bon-Conseil de Montréal, Fonds Marie Gérin-Lajoie, s.b.c., 1890-1971. Le Devoir (Montréal), 2 nov. 1945. Maryse Darsigny, “Du Comité Provincial du Suffrage Féminin à la Ligue des Droits de la Femme (1922-1940): le second souffle du mouvement féministe au Québec de la première moitié du XXe siècle” (mémoire de ma, univ. du Québec à Montréal, 1994); L’épopée du suffrage féminin au Québec, 1920-1940 ([Montréal], 1990). Les femmes dans la société québécoise, sous la dir. de Marie Lavigne et Yolande Pinard (Montréal, 1977). Karine Hébert, “Une organisation maternaliste au Québec, la Fédération Nationale Saint-Jean-Baptiste (1900-1940)” (mémoire de ma, univ. de Montréal, 1997). Danyèle Lacombe, “Marie Gérin-Lajoie’s hidden crucifixes: social Catholicism, feminism and Québec modernity, 1910-1930” (ma thesis, Univ. of Alta, Edmonton, 1998). Mireille Lebeau, Répertoire numérique détaillé du fonds Marie Gérin-Lajoie (1867-1945) (Montréal, 2000). Mireille Lebeau et Marcienne Proulx, Répertoire numérique détaillé du fonds Marie Gérin-Lajoie, SBC, 1890-1971 (Montréal, 2002). M. P. Malouin, Entre le rêve et la réalité: Marie Gérin-Lajoie et l’histoire du Bon-Conseil (Saint-Laurent [Montréal], 1998). Yolande Pinard, “Le féminisme à Montréal au commencement du XXe siècle, 1893-1920” (mémoire de ma, univ. du Québec à Montréal, 1976). Marcienne Proulx, “L’action sociale de Marie Gérin-Lajoie, 1910-1925” (mémoire de ma, univ. de Sherbrooke, Québec, 1975). Travailleuses et féministes: les femmes dans la société québécoise, sous la dir. de Marie Lavigne et Yolande Pinard (Montréal, 1983). Luigi Trifiro, “La crise de 1922 dans la lutte pour le suffrage féminin au Québec” (mémoire de ma, univ. de Sherbrooke, 1976).

Cite This Article

Anne-Marie Sicotte, “LACOSTE, MARIE (baptized Marie-Thaïs-Élodie-Coralie) (Gérin-Lajoie),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 17, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 1, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/lacoste_marie_17E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/lacoste_marie_17E.html |

| Author of Article: | Anne-Marie Sicotte |

| Title of Article: | LACOSTE, MARIE (baptized Marie-Thaïs-Élodie-Coralie) (Gérin-Lajoie) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 17 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2011 |

| Year of revision: | 2011 |

| Access Date: | January 1, 2026 |