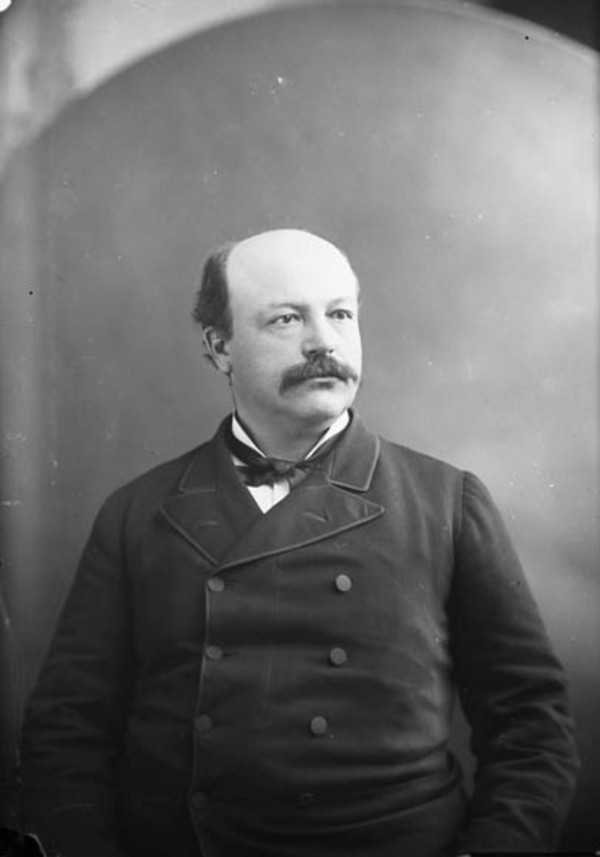

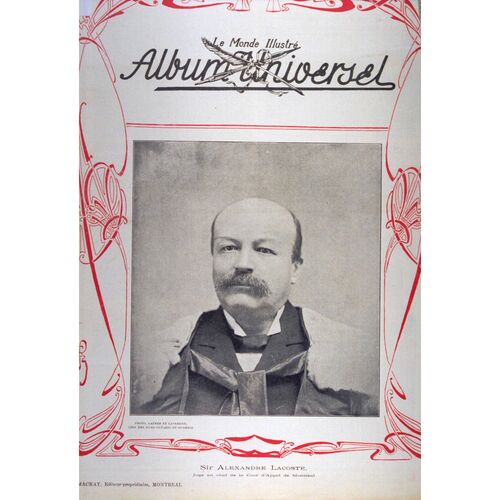

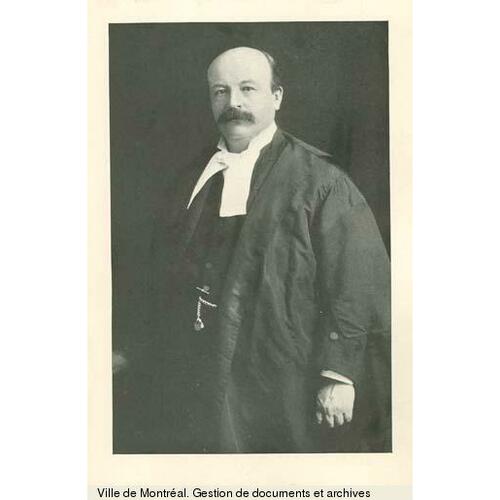

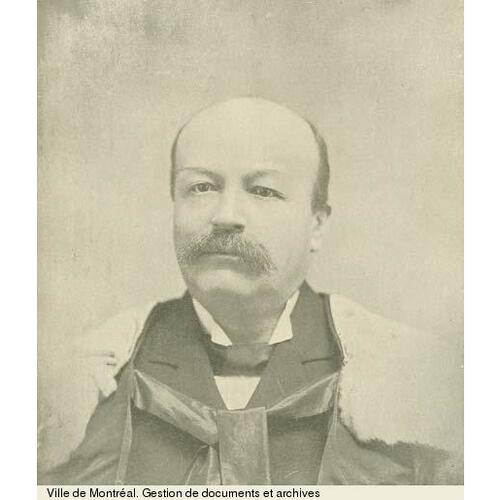

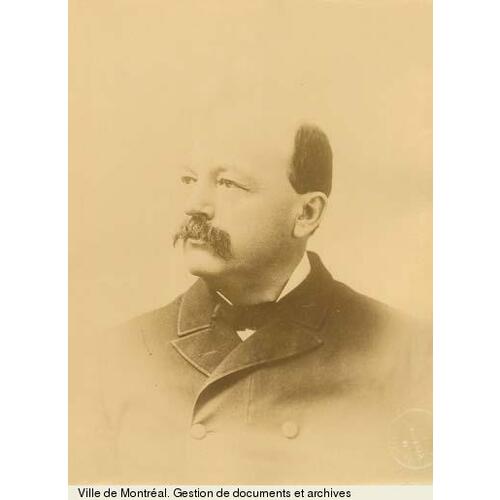

LACOSTE, Sir ALEXANDRE (baptized Alphonse-Charles-Alexandre), lawyer, professor, politician, and judge; b. 13 Jan. 1842 in Boucherville, Lower Canada, son of Louis Lacoste*, a notary and politician, and Marie-Antoinette-Thaïs Proulx; m. 8 May 1866 Marie-Louise Globensky in Montreal, and they had at least seven daughters and three sons; d. 17 Aug. 1923 in Montreal and was buried 21 August in Notre-Dame-des-Neiges cemetery there.

Alexandre Lacoste did his classical studies at the Séminaire de Saint-Hyacinthe, where he enrolled in 1851. His father’s reputation as one of the most highly regarded legal practitioners of his time no doubt drew him to a career in law. After studying at the law faculty of the Université Laval at Quebec in 1858-59, he attended the law school of the Collège Sainte-Marie in Montreal, which was directed by François-Maximilien Bibaud*; there he obtained an llb. He entered the law office of Pierre Moreau, Gédéon Ouimet*, and Joseph-Adolphe Chapleau* as a clerk. In February 1863 he passed the bar entrance examination brilliantly.

Lacoste practised as a lawyer solely in Montreal. From 1863 to 1891 he was a partner, in turn, with Isaïe-A. Jodoin, Charles-André Leblanc*, Francis Cassidy*, William D. Drummond, Benjamin-A. Globensky, Toussaint Brosseau, François-Joseph Bisaillon, and his son-in-law Henri Gérin-Lajoie. He served as bâtonnier of the Montreal bar from 1879 to 1881. Working in particular in commercial law, real estate law, and estate law, he built up a heterogeneous clientele. As a result of the connections he formed in the business world, he sat on a number of boards of directors, including those of the Manitoba Assurance Company and the Liverpool and London and Globe Insurance Company. He also became chairman of the board of control of the Banque Provinciale du Canada. Because of his activities within the Conservative party, he frequently represented politicians involved in contested elections. In 1882 the provincial government retained him as counsel and negotiator in the sale of the Quebec, Montreal, Ottawa and Occidental Railway to the Canadian Pacific Railway and the syndicate put together by Louis-Adélard Senécal* [see Sir Joseph-Adolphe Chapleau], who happened to be one of his clients. He appeared on a number of occasions before Canadian courts at different levels. He also went to London, England, to represent various clients before the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council.

Lacoste was one of the first professors in the law faculty of the Montreal branch of the Université Laval. As was customary, he was granted an honorary lld when he took up his duties in December 1879. He held the chair of commercial law and maritime law for the rest of his life. At the time he received his appointments, the expansion of the Université Laval to Montreal [see Édouard-Charles Fabre*] was meeting with opposition. There were those who questioned its right to open a branch there on the basis of the prerogatives granted in its royal charter. The university undertook to put an end to the controversy by asking the Legislative Assembly to intervene. In 1881 the rector, Thomas-Étienne Hamel, and Lacoste appeared before the committee on private members’ bills and successfully defended a measure confirming the university’s powers [see Chapleau].

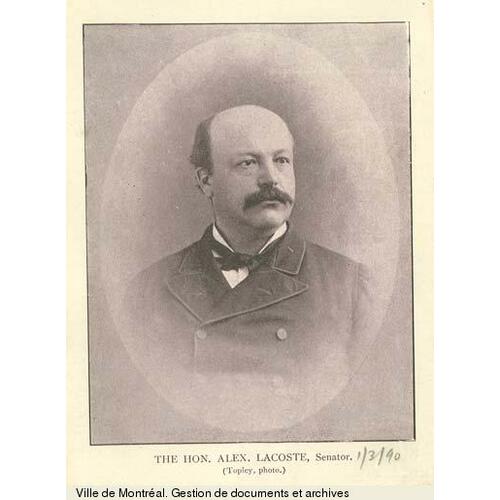

Although Lacoste, who was a moderate conservative, was interested in politics, he never sought to become an elected representative. He preferred to carry on his well-established law practice, while exerting influence within the Conservative party, where he helped to resolve thorny matters. Following the Tanneries scandal in 1874, for example, he was among those who concluded that Premier Gédéon Ouimet would have to resign. In 1880 he and a group that included Joseph Tassé*, Louis-Aimé Gélinas, and Jean-Baptiste Renaud* purchased the Conservative newspaper La Minerve. He was appointed to the Legislative Council to represent the division of Mille-Isles in 1882. Chapleau, to whom he was apparently an adviser, was premier at the time. Lacoste remained a legislative councillor until December 1883, and in January 1884 he entered the Senate to represent the division of Lorimier. Parliamentary life held little attraction for him. He rarely took the floor in the Senate and his speeches there were far from noteworthy. He concentrated his energy mainly on the work of the committee studying private members’ bills.

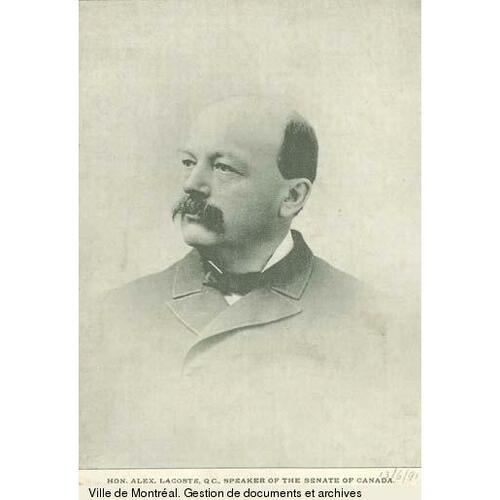

In 1891, after serving for several months as speaker of the upper house, Lacoste became chief justice of the Court of Queen’s Bench for the province of Quebec, replacing Sir Antoine-Aimé Dorion*. On accepting this prestigious appointment, however, he found that his income was reduced, especially since he stopped practising law at the same time. It was probably for this reason that he would continue to hold company directorships until the federal government forbade the judiciary to do so. According to the law reports, Lacoste frequently wrote the reasons behind the rulings on cases appealed to the Court of Queen’s Bench. His judgements were rigorous and concise, but offered scant scholarly elaboration. Unlike some of his colleagues, he confined himself to the arguments raised by the parties to a case.

At the end of the 19th century the administration of justice, in particular its high cost and the unequal division of work among the judges, was widely criticized. Around 1892 Lacoste drew up a plan for judicial reform. He proposed that the judges of the Superior Court be grouped together in large urban centres in order to share the burden more equally, work in a more collegial way, and thus develop a more coherent jurisprudence. Thomas Chase-Casgrain* introduced a bill incorporating Lacoste’s suggestions in February 1893, but it did not pass.

In 1907 Lacoste resigned from the bench and returned to the practice of law with his sons Paul and Alexandre. Shortly afterwards he agreed to become president of the Conservative Association of Montreal, a move that drew sharp criticism from his political opponents, including Prime Minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier*, who considered such conduct unacceptable in someone receiving a government pension.

An open-minded man, Lacoste likely encouraged his daughters to participate in social life. Their mother, a ready supporter of charities who for more than 30 years kept a diary chronicling the developments in their life as a middle-class Montreal family, certainly also encouraged such activity. Marie* and Thaïs, who taught themselves the rudiments of law, campaigned for more civil rights for women through their lectures and writings; Justine founded the Hôpital Sainte-Justine in Montreal in 1907. Interested in matters relating to education, Lacoste collaborated, in particular, in a series of lectures on ordinary law for teachers that was organized by Marie in 1905.

Over the years, Lacoste received many honours. He was named a qc by the provincial government in 1876 and by the federal government in 1880. In 1892 he was made a kcmg. Bishop’s College gave him an honorary doctorate in 1895.

Alexandre Lacoste remained firmly attached to a rational approach to the law, as Laurent-Olivier David recalled in Au soir de la vie: “Nothing brilliant, little polish in his arguments in court or his judicial decisions, but plenty of logic, force, and clarity.” In this respect, he was the model of the kind of lawyer who would increasingly be seen at the beginning of the 20th century. His character traits, his passion for the law, and his success no doubt explain why he was unwilling to sacrifice his professional career in order to hold prominent offices in the world of politics. Despite this reluctance, he agreed to sit in the upper houses of the province and the country. Close to the seat of power, he played a role as an influential, but discreet, adviser to the Conservative party.

ANQ-M, CE601-S22, 13 janv. 1842; CE601-S51, 8 mai 1866; P76. Le Canada (Montréal), 18 août 1923. Le Devoir, 21 janv. 1919, 17 août 1923. Gazette (Montreal), 24 Oct. 1908; 18, 23 Aug. 1923. Montreal Daily Star, 17 Aug. 1923. La Patrie, 17-18, 21 août 1923. La Presse, 17 août 1923. F.-J. Audet, Les juges en chef de la province de Québec, 1764-1924 (Québec, 1927). L.-P. Audet, Histoire de l’enseignement au Québec (2v., Montréal et Toronto, 1971), 2. BCF, 1920: 23. [F.-M.] Bibaud, Supplément à la “Notice historique sur l’enseignement du droit” ([Montréal?, 1862?]). Can., Senate, Debates, 1884-91; Journals, 1884-91. Canada Gazette, 16 Oct. 1880: 419; 22 Oct. 1892: 767; 25 March 1893: 1767; 10 April 1897: 2015. Canadian directory of parl. (Johnson). CPG, 1887, 1897. L.-O. David, Au soir de la vie (Montréal, [1924]). Directory, Montreal, 1863-91. DPQ. A[lfred] D[uclos] De Celles, “Sir Alexandre Lacoste,” trans. Mrs Carroll Ryan [M. A. McIver], in Men of the day: a Canadian portrait gallery, ed. L.-H. Taché (32 ser. in 16v., Montreal, 1890-[94]), 18th ser.: 273-82. [Édouard Fabre] Surveyer, “Sir Alexandre Lacoste,” Canadian Bar Rev. (Toronto), 1 (1923): 757-62. T.-É. Hamel et Alexandre Lacoste, Plaidoyers de MM. Hamel et Lacoste devant le comité des bills privés en faveur de l’université Laval les 20, 21, 27 et 28 mai 1881 (Québec, 1881). Jean Hétu, Album souvenir, 1878-1978; centenaire de la faculté de droit de l’université de Montréal (Montréal, 1978). Nicholas Kasirer, “Apostolat juridique: teaching everyday law in the life of Marie Lacoste Gérin-Lajoie (1867-1945),” Osgoode Hall Law Journal (Toronto), 30 (1992): 427-70. J.-J. Lefebvre, “Tableau alphabétique des avocats de la province de Québec, 1850-1868,” La Rev. du Barreau de la prov. de Québec (Montréal), 21 (1961): 314-32. Prominent men of Canada: a collection of persons distinguished in professional and political life, and in the commerce and industry of Canada, ed. G. M. Adam (Toronto, 1892). Qué., Parl., Doc. de la session, réponses aux adresses, no.13, 1888. Quebec Official Gazette, 1876: 488. Quebec Official Reports: King’s Bench (Quebec), 1892-1907. G.-É. Rinfret, Histoire du barreau de Montréal (Cowansville, Qué., 1989). P.-G. Roy, Les juges de la prov. de Québec. Rumilly, Hist. de la prov. de Québec, vols.2-26. [F.-]X.-A. Trudel et al., Réplique aux plaidoyers de MM. Hamel et Lacoste: Rome 25 septembre 1881 ([Rome?, 1882?]). Gustave Turcotte, Le Conseil législatif de Québec, 1774-1933 (Beauceville, Qué., 1933). Univ. Laval, Annuaire, 1859-60, 1880-81.

Cite This Article

Sylvio Normand, “LACOSTE, Sir ALEXANDRE (baptized Alphonse-Charles-Alexandre),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 25, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/lacoste_alexandre_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/lacoste_alexandre_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | Sylvio Normand |

| Title of Article: | LACOSTE, Sir ALEXANDRE (baptized Alphonse-Charles-Alexandre) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | April 25, 2025 |