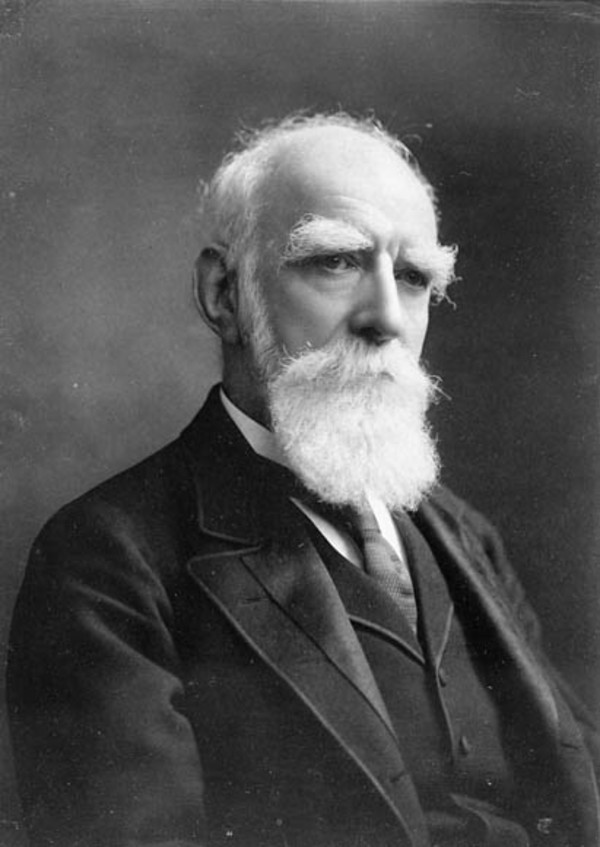

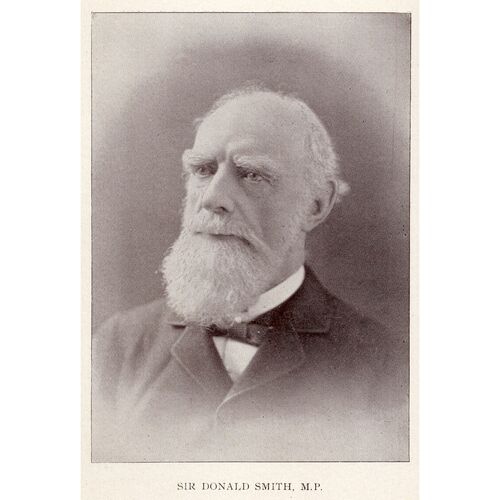

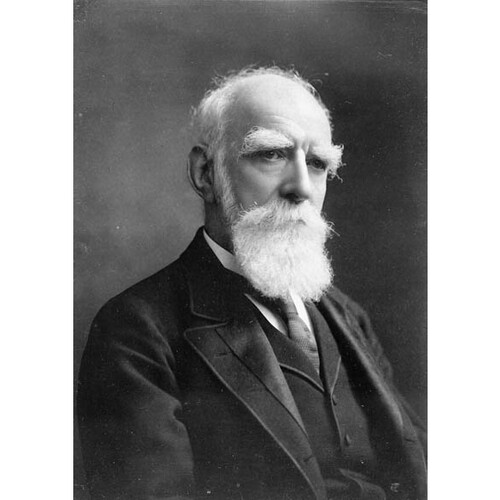

SMITH, DONALD ALEXANDER, 1st Baron STRATHCONA and MOUNT ROYAL, HBC officer, businessman, politician, diplomat, and philanthropist; b. 6 Aug. 1820 in Forres, Scotland, son of Alexander Smith and Barbara Stuart; m. Isabella Sophia Hardisty, sister of Richard Charles* and William Lucas* Hardisty, and they had one daughter; d. 21 Jan. 1914 in London, England.

Donald Smith was born on Scotland’s northeast coast. After attending Forres Academy he was briefly apprenticed to the town clerk. Inspired by the exploits of fur trader John Stuart*, his mother’s brother, he sought to join the Hudson’s Bay Company. He embarked for Lower Canada on 16 May 1838. Soon after his arrival he was hired as an apprentice clerk in Lachine. A few weeks later he was seconded to Tadoussac under William Connolly*. His starting salary was £20 per annum and rose yearly until he was made clerk in 1842 at a salary of £100. Late in 1843 he was appointed to take charge of the seigneury of Mingan, a territory east of Tadoussac extending to the Labrador coast. Although he was considered thoughtful and enterprising, his administrative methods provoked the ire of HBC governor Sir George Simpson* during an inspection tour of Smith’s post in the summer of 1845. Simpson rebuked him for the slovenly condition of the counting-house, irregular methods of bookkeeping, and the late submission of the annual accounts. Simpson’s frustration may also have been prompted by Smith’s poor handwriting, which only deteriorated over time. In 1846 the Mingan post burned down, but Smith remained in charge until late in 1847 when he left for Montreal to get attention for his eyes, which had apparently been injured in the fire.

In January 1848 Smith was sent to relieve chief factor William Nourse in the Esquimaux Bay district (Hamilton Inlet), Labrador. Accompanied by three native guides and a distant cousin, apprentice clerk James Grant, he travelled overland, reaching North West River in June. On the arrival of chief trader Richard Hardisty and his family in August, Smith was left to manage the post at Rigolet. Hardisty went on furlough in 1852 and partly on his recommendation Smith was appointed chief trader on 7 April. Hardisty’s daughter Isabella moved in with Smith and gave birth to their daughter, Margaret Charlotte, on 17 Jan. 1854. Isabella, whose mother was of native and Scottish parentage, had married James Grant in July 1851, likely in a ceremony performed by her father. She had given birth to a son, James Hardisty Grant, in July 1852, but the couple had separated soon after, apparently by mutual consent. The circumstances of Smith’s marriage proved to be a lifelong embarrassment to him. His wife’s first alliance, à la façon du pays, and its termination had no legal standing. Smith was impelled to have his union solemnized on several occasions. Partly at Simpson’s suggestion and to put an end to gossip, he conducted his own wedding ceremony in North West River in June 1859, although he generally used 9 March 1853 as the official date of their marriage. Later in life they were married at the Windsor Hotel in New York City on 9 March 1896 before his Wall Street lawyers, John William Sterling and Thomas Gaskell Shearman. Throughout their lives the couple endured gossip, but it did not affect Smith’s devotion to his wife. When apart he wrote or cabled her every day. Her son took his surname and Smith assisted him in numerous ways. At Smith’s death, newspapers speculated that his stepson would demand a share of the estate, but he renounced any claim. James Hardisty Smith was left his stepfather’s country house in Pictou, N.S., and the income from a trust fund of $125,000 established for his children.

In his Labrador post Smith had proved to be enterprising and innovative. His administrative methods earned him occasional reproaches from Simpson, but he developed profitable sidelines to the fur trade, encouraging the HBC to invest in transport ships and developing a successful salmon cannery. In 1862 he was promoted chief factor in charge of the Labrador district. His promotion brought him more frequently to the company headquarters in Montreal, where in 1865 he first met his cousin George Stephen*. By that time Stephen was a substantial investor in textile mills and rolling-stock companies. Within several years they would be in partnership with leaders of the Montreal business community. Stephen provided investment advice and Smith offered him help selling his woollen goods to the HBC. In 1868 Smith joined Stephen, Richard Bladworth Angus*, and Andrew Paton* in the Paton Manufacturing Company of Sherbrooke. The following year he was a partner with Stephen, Hugh* and Andrew* Allan, Edwin Henry King*, and Robert James Reekie in the Canada Rolling Stock Company.

Smith’s knowledge of the HBC’s operations and opportunities was remarked on when, on furlough in London in 1865, he met its new administrators. Controlling interest in the HBC had been acquired by the International Financial Society in 1863 in a transaction which transformed it from a privately held company into a public firm with shares trading on the London stock exchange. The new directors were as much interested in land development as they were in the fur trade, a point which caused endless anxiety to the wintering partners in Canada, most of whom believed colonization to be incompatible with the fur trade. After having ingratiated himself with the London committee, Smith was promoted commissioner of the Montreal department in 1868 to manage the HBC’s eastern operations.

In the spring of 1869 negotiations for the transfer of the HBC territories to Canada were concluded in London. In the Red River settlement (Man.) Métis leader Louis Riel* assumed leadership of the resistance to the proposed transfer. On 10 Dec. 1869 Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald* appointed Smith a special commissioner to help defuse the growing tensions. He was to join two other commissioners, Jean-Baptiste Thibault* and Charles-René-Léonidas d’Irumberry* de Salaberry. Smith arrived at Upper Fort Garry (Winnipeg) on 27 Dec. 1869 accompanied by Richard Charles Hardisty. He used his influence as an HBC officer and bribes to attempt a peaceful settlement and to secure the release of members of the Canadian party [see Sir John Christian Schultz*] who had been incarcerated since 7 December. After his meeting with Riel on 6 Jan. 1870, he concluded that negotiations with Riel’s council would not accomplish anything. A public meeting was held on 19 and 20 January at which Smith presented the instructions he had received from Macdonald and the government’s promise to confirm the inhabitants’ land titles and to grant representation on a territorial council. Riel responded by proposing a convention of 40 representatives to consider Smith’s instructions. On 7 February Smith invited the convention to send a delegation to Ottawa to negotiate. In the meantime Schultz, Charles Mair*, and Thomas Scott* had raised a group of volunteers to overthrow Riel and rescue those he had imprisoned. Most of the volunteers were promptly captured by Riel’s men near Upper Fort Garry on the 15th of that month. Charles Arkoll Boulton* and three others were sentenced to death, but Riel relented after he obtained a promise from Smith to secure support for the provisional government from the English parishes of the settlement. Smith’s pleas for clemency were not successful, however, in averting the execution of Scott on 4 March. Smith and Hardisty left Upper Fort Garry 15 days later to report to Macdonald in Ottawa.

Fresh from his success in Red River, Smith was appointed president of the HBC’s Council of the Northern Department, since William Mactavish*, HBC governor of Rupert’s Land and governor of Assiniboia, had resigned because of ill health. In June he attended its meeting at Norway House (Man.) and then left for Red River, arriving in August with Colonel Garnet Joseph Wolseley, leader of the military expedition sent to pacify the rebellion. At Wolseley’s request he served briefly as acting governor of Assiniboia until the arrival of Adams George Archibald*, lieutenant governor of Manitoba and the North-West Territories. Asked to stay on as temporary head of the Northern Department, Smith would play a leading role in negotiating with the Canadian government the implications of the transfer and in reorganizing the HBC’s operations in the northwest. A deed poll of 1871 transformed the profit-sharing arrangement with the wintering partners which had governed the company’s fur trade operations since 1821. Henceforward, chief factors and chief traders were to be guaranteed an annual income and were to share in the profits of the fur and general trade, but not in the profits from the sale of HBC land or territories. Smith’s role in this negotiation was vital for the company and for his career. At Norway House the previous spring he had been mandated by the wintering partners to represent them before the governor and committee. The resulting agreement pleased the majority of them, but evoked bitter criticism from several who accused Smith of sacrificing them to advance his own career and of forfeiting their claim to a share of the company’s land sales. Smith was rewarded for his deft negotiation with the nomination of chief commissioner, which brought him a salary of £1,500 and exempted him from the profit-sharing agreement he had negotiated. As the HBC’s executive officer in Canada, he would lead the firm’s transformation into a land and colonization company.

Apparently encouraged by his superiors, Smith had become increasingly active in the politics of the northwest. On 20 Oct. 1870 he had been appointed to the executive council by Archibald, who had, however, unknowingly exceeded his authority [see Sir Francis Godschall Johnson*]. Late that December he defeated Schultz in his bid to sit for Winnipeg and St John in the Legislative Assembly of Manitoba. In a by-election on 2 March 1871 Smith was elected to the House of Commons for Selkirk, and he was re-elected in the general election of 1872. Although a Conservative, Smith did not take an active role in partisan politics. So one-dimensional were his interventions that he was referred to as the honourable member for the HBC. He spoke sparingly in the commons, on issues touching Manitoba and the northwest.

On 5 Nov. 1873 Smith helped to bring down Macdonald’s government. He had long been angry that Macdonald had ignored his repeated requests for repayment of his expenses as commissioner to Red River. Called to vote on a motion to censure the government over the Pacific Scandal, he pressed his claim once more, but Macdonald, in an advanced state of depression and intoxication when the two men met, only made matters worse. With Smith’s defection Macdonald’s already diminished majority was lost. The event left Macdonald embittered and strained the relations between the two men in the years to follow.

The federal government had abolished the double mandate in May 1873, so Smith resigned his provincial seat the following January. In the federal election of 1874 his opponent was his sometime partner and friend Andrew Graham Ballenden Bannatyne*, who the Manitoba Free Press suggested was a straw man put forward to ensure Smith’s victory. His relationship with Conservative members of the commons was characterized by bitter exchanges and insults. Smith’s bill was not settled until 1875, when the motion to pay him £600 plus interest passed only after a rancorous debate. In the general election of 1878 Smith defeated former lieutenant governor of Manitoba Alexander Morris* in Selkirk by 10 votes, aided by generous support from the Free Press. Two ardent Conservatives, David Young* and Archibald Wright, protested the election on the grounds of corrupt practices. They were at first unsuccessful, but appealed to the Supreme Court of Canada and Smith was unseated in 1880. In the ensuing by-election on 10 September Smith was defeated and withdrew from politics.

As chief commissioner of the HBC, Smith modernized the company’s slow and costly transportation network. The HBC, and many of its principal shareholders acting as private investors, became directly involved in these developments, which transformed the northwest. He encouraged the company to build its own fleet of steamboats to move goods on lakes Winnipeg and Winnipegosis. In May 1872 the HBC launched the Chief Commissioner, named in his honour, but it proved unsuitable for the rough waters of Lake Winnipeg. Other vessels were more successful and were soon profitable. Although Smith’s early transportation efforts showed all the signs of ill planning, subsequent attempts rapidly demonstrated their effectiveness.

During the early 1870s Smith was involved in the formation of businesses in Manitoba. In 1872 he sponsored bills to incorporate the Bank of Manitoba, the Central Telegraph Company, and the Manitoba Insurance Company, which he founded with Bannatyne and Sir Hugh Allan. While none of these businesses were very prosperous, they indicate that he was increasingly the individual through whom many in the Montreal financial community were investing in Manitoba. His business interests elsewhere were also multiplying. In 1872, along with Stephen, Bennett Rosamond*, and Donald McInnes*, he became a shareholder in the Canada Cotton Manufacturing Company, and 10 years later he would join with Stephen and Stephen’s brother-in-law, James Alexander Cantlie, to provide capital to found the Almonte Knitting Company, an expansion of Rosamond’s firm.

Smith profited from his position in the HBC to survey business opportunities both for the company and for himself. In the early 1870s the HBC was being solicited to take an interest in railways and Smith himself was involved in a number of ventures. A syndicate which included Smith, Stephen, Sir Alexander Tilloch Galt*, George Laidlaw*, and others applied for a charter to build the Manitoba Junction Railway from Pembina (N.Dak.) to Fort Garry in 1871 and many of the same men sought a charter to build from Fort Garry to Fort William (Thunder Bay, Ont.). By 1872 Smith’s name was linked with the proposed railway to the Pacific, although he publicly denied his involvement. In 1875 he was among the incorporators of the Manitoba Western Railway, which was to run from Lake Manitoba to St Joseph (Walhalla, N.Dak.).

Undoubtedly, Smith’s business ventures distracted him from his management of the HBC’s affairs. He received periodic rebukes from Governor Sir Stafford Henry Northcote who complained that he had to report on land sales based on information gleaned from newspapers. Inspecting chief factor William Joseph Christie*, after his return from an inspection of the company posts in January 1873, fumed that Smith was neglecting the fur trade. Christie travelled to England to report to the London committee about the negligent management of the company’s affairs. Smith followed to plead his own case. Christie eventually resigned when no action was taken. In July 1873, however, the HBC formally separated the fur trade and land sales operations and made Smith land commissioner, placing him in charge of the company’s western operations other than the fur trade. James Allan Grahame* succeeded him as chief commissioner in 1874.

Smith’s interest in steamers had brought him in close contact with businessmen from St Paul, Minn., including James Jerome Hill and Norman Wolfred Kittson*, a shipping agent for the HBC since 1862. Smith had met Hill during the Riel rebellion and they shared an interest in improving transportation in the northwest. In 1872 Hill, Kittson, and Smith (acting for the HBC) formed the profitable Red River Transportation Company. During 1873 and 1874 Smith conferred with Hill about the possibility of acquiring the St Paul and Pacific Railroad. Under construction from St Paul north to the Red River since the 1860s, it had fallen into receivership. In March 1876 Hill met Smith in Ottawa to finalize a partnership agreement. Although he and Kittson had extensive experience in transportation, they had little capital. Smith went to Stephen. Stephen turned to the established New York banking house of J. S. Kennedy and Company and to the Bank of Montreal, of which he was president. By March 1878 the group had obtained control of the railway and had begun building north to the border. At the same time Stephen and Smith attempted to negotiate an agreement with the Liberal government of Alexander Mackenzie* to lease the line it was building from St Boniface to Pembina, and encountered strong opposition from Conservative leaders in parliament. The syndicate completed the line to the border in November 1878 and then went on to connect with the Canadian line. The first train arrived in St Boniface on 3 December. The following May the St Paul, Minneapolis and Manitoba Railroad Company was created with Smith as a director, owning one-fifth of its shares. The investment was the foundation of his, Stephen’s, and several other fortunes. Soon after its completion the line showed an operating profit and consistently produced extraordinary dividends and returns.

In 1878 Smith was delegated by the wintering partners of the HBC to present their demand for an annual salary of £200 for each share to the London committee. The HBC offered £150, which the officers at first rejected. In the face of obdurate directors and shareholders, Smith was able to persuade his colleagues to accept the offer. Although he had lost the support of some commissioned officers, most acknowledged that Smith was the best person to represent them since no one else had the same weight with the board or the shareholders.

On 25 Feb. 1879 Smith resigned as land commissioner, claiming that his “private affairs” required more of his attention, but he remained as an adviser to the company. His growing involvement in railways brought him into direct conflict with his successor, Charles John Brydges*, who had been appointed to consolidate the company’s operations. Smith and Brydges would feud on several occasions. Brydges suspected that Smith schemed to ruin the reputation of the HBC and then buy its reduced shares. Smith did indeed acquire considerable stock. By 1882 he had 2,000 shares and between 1883 to 1891 his holdings rose to 4,000 shares. Smith saw Brydges as a challenge to his plans and reputation and as an enemy of the Canadian Pacific Railway. In 1882 a review of Brydges’s administration vindicated him, but a supervisory committee consisting of Smith and Sandford Fleming was appointed two years later to advise the London board. Smith’s troubles with Brydges may have pushed him to seek control of the HBC, which he would effectively achieve by 1889 when he was the principal shareholder and was elected governor.

In 1880 Stephen had begun negotiations with Macdonald for the contract to build and operate the transcontinental railway. Smith’s place in the syndicate organized by Stephen was well known but not publicly announced in deference to the lingering animosity Macdonald and other Conservatives had towards him. Although annoyed by the omission, Smith did not officially become a director until 1883, following Hill’s resignation. While he played a secondary role in the management of the railway and its construction, he was a faithful financial lieutenant to Stephen. In addition to being a substantial shareholder in the CPR, he was also a principal shareholder in the railways which had been acquired in order to complete the CPR’s eastern lines, the Toronto, Grey and Bruce, the Credit Valley, the Ontario and Quebec, and the New Brunswick. Throughout 1884–85, when financing the CPR became increasingly difficult, Stephen and Smith pledged their homes, their investments, and their holdings in the St Paul, Minneapolis and Manitoba as collateral and took money from their own accounts to provide operating funds. Smith’s major importance to the syndicate lay in his financial and moral support; he did not desert the railway as directors Duncan McIntyre*, Hill, and others had done. On 7 Nov. 1885 he drove the last spike during a modest ceremony in Craigellachie, B.C., one of many places in the west named in honour of Smith, Stephen, or their homeland.

When Stephen resigned from the presidency of the CPR on 7 Aug. 1888, Smith apparently expected to be named his successor, but the post went to the vice-president and general manager, William Cornelius Van Horne. Smith remained on the executive committee long after Stephen had retired. As the CPR began its transformation into an operating railway, Smith and Stephen became large investors in the many companies which were its dependencies, such as the Lake of the Woods Milling Company Limited [see Robert Meighen], the Canada North West Land Company [see William Bain Scarth*], and the Canadian Salt Company Limited. Along with Van Horne and Stephen, Smith invested heavily in Vancouver real estate. Although less than enamoured of the returns of the CPR, Stephen and Smith combined to protect it from competitors. In 1888 they extended its reach into the United States by acquiring the Minneapolis, St Paul and Sault Ste Marie and the Duluth, South Shore and Atlantic. In 1888 Smith was a founding partner, along with R. B. Angus, Van Horne, and Charles Rudolph Hosmer, in the Federal Telephone Company, which ran the telephone service in Montreal until it sold out to the Bell Telephone [see Charles Fleetford Sise] in 1891. In 1893 Smith was part of the syndicate put together by Boston financier Henry Melville Whitney* to form the Dominion Coal Company Limited. Smith’s holdings in the CPR were relatively minor. In 1901 he held only 5,000 shares. He and Stephen reserved their most substantial railway investments for Hill’s expanding railway empire. Their St Paul shares were converted on several occasions, after Hill acquired controlling interest in the Great Northern and other railroads. When the Northern Pacific, the Great Northern, and a third line, the Chicago, Burlington and Quincy, were briefly combined in 1901 into a holding company, the Northern Securities Company Limited, Smith was the third largest shareholder after Hill and John Stewart Kennedy, with 54,000 shares then worth $115 each.

Smith was involved in a legion of corporations as a shareholder, director, or chairman. His involvement with the Bank of Montreal began in 1872 when he was first appointed to the board. He was made vice-president in June 1882 and president in 1887. Although not entirely ceremonial, his role at the bank was largely limited to board and annual meetings. George Alexander Drummond* acted as de facto president for much of Smith’s tenure. In 1904 Smith asked to be replaced and the following year he was appointed honorary president, a title he held until his death. Guaranteed to bring respectability and a personal investment, Smith was often asked to serve as chairman of fledgling financial institutions. In 1891 he became the first president of the Montreal Safe Deposit Company (later Montreal Trust). In 1899 he took on the presidency of the Royal Trust Company, largely formed by directors of the Bank of Montreal. He sat on many boards, including those of the London and Lancashire Life Assurance Company, the Paton Manufacturing Company, the New Brunswick Railway Company, the Dominion Coal Company, the Northern Life Assurance Company, the London and Canadian Loan and Agency Company, the International Commercial Association, and the Canadian Bankers’ Association.

Sometimes on his own behalf, sometimes acting for others, Smith had interests in several Canadian newspapers. In 1882 he unsuccessfully attempted to acquire the Toronto Globe in order to stem its criticism of the CPR [see Robert Jaffray]. In 1888 he loaned money to the editor of the Manitoba Free Press, William Fisher Luxton*. He called in the loan five years later and took control of the paper. Luxton was removed and replaced with one of the CPR’s publicity agents. The paper was sold to Clifford Sifton* in 1898.

After re-entering the House of Commons as an independent Conservative for Montreal West in 1887, Smith was re-elected in 1891 with the largest majority in Canada. At the urging of the Governor General Lord Aberdeen [Hamilton-Gordon*], in February 1896 he attempted to broker an agreement between the Manitoba government of Thomas Greenway* and Roman Catholic leaders who opposed the creation of a single, publicly funded, non-denominational school system. His negotiations with Father Albert Lacombe, Archbishop Adélard Langevin, and Greenway were not sufficient to generate support for the remedial legislation introduced by the government of Sir Mackenzie Bowell. In his last speech in the commons, on 19 March 1896, Smith urged passage of the remedial bill. Bowell, who would resign on 27 April, preferred Smith to Sir Charles Tupper as his successor, but Smith had declined the post. Tupper had become effectively leader of the government after his election in February and he appointed Smith to replace him as high commissioner in London on 24 April 1896.

After Wilfrid Laurier took office in July 1896, he retained Smith as high commissioner, but he also permitted his ministers to bypass the high commissioner’s office at will. Since the high commissioner was responsible for the supervision of immigration, Sifton, the minister of the interior, worked with him to extend the clandestine network for the enticement of immigrants from Europe by paying bonuses to steamship agents. Although the strategy provoked official protests from the German government, it was maintained. Smith generally advocated liberal immigration policies. His scheme to promote immigration from Barbados was discouraged by Sifton, who thought blacks unsuitable as prairie settlers. Frustrated by Smith’s independence, Sifton appointed Liberal organizer William Thomas Rochester Preston* to direct new immigration offices in London on 13 Jan. 1899. Smith and Preston established the North Atlantic Trading Company to bring together steamship agents for the promotion of emigration but rapidly crossed swords on a variety of matters. Preston was eventually removed from office. His dismissal provoked him to write a biography of Smith, The life and times of Lord Strathcona (London, 1914), replete with insinuations that Smith’s fortune was built on financial improprieties.

During the politically charged debate over Canadian participation in the South African War, Smith made a public offer to the British government early in 1900 to raise and equip a regiment at his own expense. To avoid controversy the unit was to be recruited in Canada but was to be part of the British army. Samuel Benfield Steele of the North-West Mounted Police was selected to recruit and to command the unit, subsequently known as Lord Strathcona’s Horse. The equipping of the regiment, which consisted of 28 officers and 572 non-commissioned officers, was estimated to have cost in excess of $1 million, one of Smith’s most munificent donations. Although Smith’s offer provided an escape for the Laurier government and was well received by the Canadian public, it was denounced by Henri Bourassa* and other anti-imperialists.

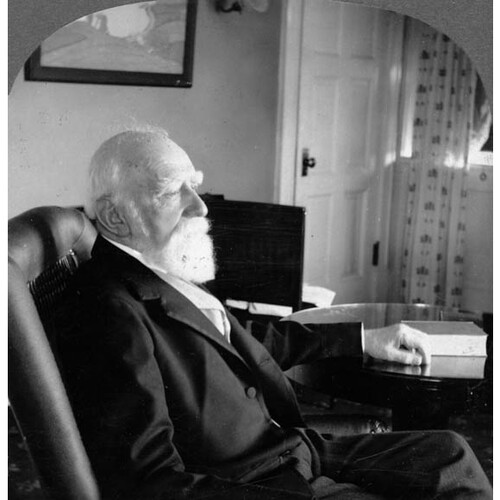

In spite of his age Smith was a tireless worker. He refused to accept his salary of $10,000 as high commissioner. He tendered his resignation in 1909, but Laurier asked him to remain in office. On 30 June 1911 the prime minister announced that he would be replaced by Sir Frederick William Borden, but his government fell before the appointment was made. Smith again offered his resignation when Robert Laird Borden* took office, but it was refused and he remained at the post until his death.

By the conclusion of the South African War Smith was perhaps the most identifiable imperial figure in London. Combining the assets of wealth, maturity, generosity, and vigour, he had an immensely broad appeal. His stature was confirmed in 1904 when he was approached by William Knox D’Arcy, who was searching for oil in Persia, to head a syndicate which would include the Burmah Oil Company. The venture appealed to Smith’s belief in the empire and had the approval of various departments of the British government, anxious for a foothold in Persia and for fuel for the British navy. Smith subscribed £50,000 with little hesitation. He also played a role in the Anglo-Persian Oil Company Limited, which was formed out of Burmah Oil to exploit its discoveries in Persia. He became the company’s first chairman in February 1909. Although by then an octogenarian, he was far from a titular chairman. He participated in the establishment of the company and its share structure and in the choice of bankers, brokers, and directors. He was the largest individual shareholder, with 30,000 of its 1,000,000 ordinary shares. His influence was also vital in establishing the company as the principal supplier to the British navy. He played a key role in staving off amalgamation with Royal Dutch Shell, persuading the British government to acquire two-thirds of the company’s shares, the embryo of British Petroleum. Smith remained chairman until his death and his family continued as substantial shareholders.

Smith’s accomplishments brought him a series of honours. Appointed a kcmg in May 1886 for his role in building the CPR, ten years later he was made a gmcg. On 14 April 1896 he had become a member of the Privy Council of Canada. In the spring of 1897 Colonial Secretary Joseph Chamberlain informed him that he was to be made a peer. When news leaked out that he had chosen the title Lord Glencoe, after a glen where Scottish chieftains had been slaughtered in 1692, a glen he had only recently acquired, colleagues prevailed on him to reconsider. He created the name Strathcona, a Gaelic variant on Glencoe. Lobbying by Tupper and Chamberlain allowed his first peerage to be superseded by a second, created on 26 June 1900, permitting the title to pass to the male heirs of his daughter. Smith delivered his maiden speech in the House of Lords in the summer of 1898. He was named a fellow of the Royal Society of London in 1904, when he was given the Albert Medal for his services to railways. He was made a gcvo in 1908 and a knight of grace of the Order of St John of Jerusalem in 1910.

Ranking among the most generous philanthropists of the early 20th century, Smith gave in excess of $7,500,000 in donations and bequests. His first significant benefaction came in 1883, when he contributed $30,000 to the Trafalgar Institute, a girl’s school in Montreal. His most important donations came after the completion of the CPR and were often made jointly with Stephen. In 1887 they announced a gift of $1,000,000 for the construction of a free hospital in Montreal and purchased a site on Mount Royal for $86,000. The Royal Victoria Hospital opened in 1893. During 1897 and 1898 Smith endowed the hospital with $1,000,000 in Great Northern Railroad securities. In 1902 he matched Stephen’s donation of £200,000 to the King Edward’s Hospital Fund, established to assist London’s hospitals. He left a bequest of £10,000 to the Leanchoil Hospital in Forres, and £8,000 to other hospitals in the United Kingdom.

Smith’s greatest benefactions were reserved for McGill University. On 11 Sept. 1884 he asked Sir John William Dawson*, the principal of McGill, whether the university would accept a gift of $50,000 to endow the first two years of separate classes for women. Although his offer came without prompting from Dawson and did not entirely concur with his views about educating women, McGill accepted. The reasons for Smith’s interest in women’s education are not known, but historian Margaret Gillett has suggested that Smith was encouraged in these donations to McGill by Montreal educator Lucy Stanynought (Simpson). McGill’s first women students were styled the Donaldas, in recognition of the donor. He gave a further $70,000 on 16 Oct. 1886 to pay for the third and fourth years, completing what was to be known as the Donalda Endowment for the Higher Education of Women. In 1896 he began the realization of his promise to build a separate college for women students. He gave $300,000 for the construction of Royal Victoria College and engaged architect Bruce Price* to design the building. When another of McGill’s benefactors, Sir William Christopher Macdonald, suggested that the new building would be a financial burden to McGill, Smith established an endowment of $1,000,000. The college was formally opened in 1900.

A generous supporter of McGill’s faculty of medicine, Smith had contributed $50,000 to its endowment in 1883. In 1888 his only child, Margaret, married Dr Robert Jared Bliss Howard, son of Dr Robert Palmer Howard*, dean of the faculty. Although Smith and his wife had not viewed the marriage entirely favourably, Smith thereafter became a major benefactor of the faculty, donating $750,000 during his lifetime. He gave funds for the construction of a building at McGill for the Young Men’s Christian Association which took the name Strathcona Hall. He provided $100,000 to the minister of militia and defence for officers’ training quarters at McGill. Made a trustee of McGill soon after his first gift, he was elected chancellor in 1888 and performed ceremonial roles until his death. In 1894–95 he was responsible for recruiting William Peterson* as principal.

Smith did not confine his donations to McGill. In 1899 he was induced by Joseph Chamberlain, the chancellor of the University of Birmingham, to make a gift of £50,000 to the university’s fund-raising campaign. In 1904 he pledged $20,000 to the University of Manitoba. He had been involved in the affairs of the colleges which would eventually form the university since the early 1870s when he offered a land grant from the HBC as the site for Wesley College and began 40 years’ service (1874–1914) on the board of management of Manitoba College. Nevertheless, he ignored the university in his bequests. He was rector of the University of Aberdeen from 1899 to 1902 and acted as chancellor until his death. For its quatercentenary in 1906 he gave a feast that was legendary in its time, building a 3,000-seat hall for the event. He gave $500,000 to Yale University, £10,000 to the University of Aberdeen and £30,000 to its Marischal College, and donations to other universities and colleges in Canada, Great Britain, and the United States too many to mention. His chancellorships and benefactions prompted at least 14 universities to grant him honorary degrees.

His other gifts are so numerous that they cannot be fully itemized. In 1902, for instance, he made about 120 donations, large ones to universities and smaller ones to such organizations as churches, snowshoe clubs, boys’ brigades, and monasteries. His benefactions were sometimes anonymous and at other times highly publicized. A patron of music, he endowed scholarships in Montreal and at the Royal College of Music in England to enable Canadians to study there. Encouraged by the minister of militia and defence, Sir Frederick William Borden, Smith made a donation towards military training for the young. The Strathcona Trust, as the fund came to be known, was the catalyst which led communities and schools to promote drill and physical training. With his gifts of more than $500,000, the trust developed the cadet movement, which by 1913 had 40,000 members. He donated $150,000 to fund YMCA buildings in Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta, and Nova Scotia. Godfather to the son of Robert Stephenson Smyth Baden-Powell, he assisted the formation of the Boy Scout movement and left a bequest to aid its development in Canada. He was the principal supporter of Wilfred Thomason Grenfell*, the English doctor who founded missions to the communities along the coasts of Newfoundland and Labrador. He gave Grenfell a steamer, the Sir Donald, for use as a hospital ship and replaced it in 1899 with the steel steamer Strathcona. A parishioner of St Paul’s Presbyterian Church in Montreal, he made an anonymous donation of an organ to it and left a bequest of $25,000 to the Presbyterian College of Montreal.

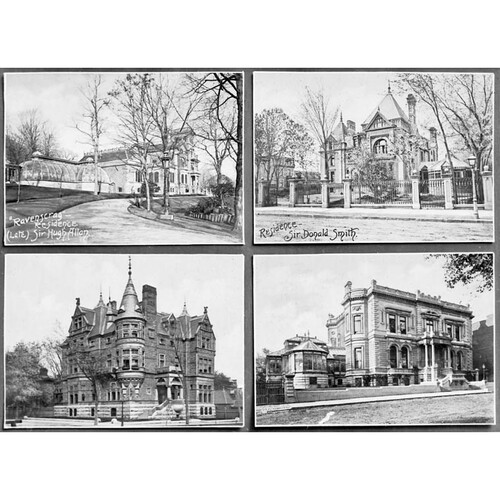

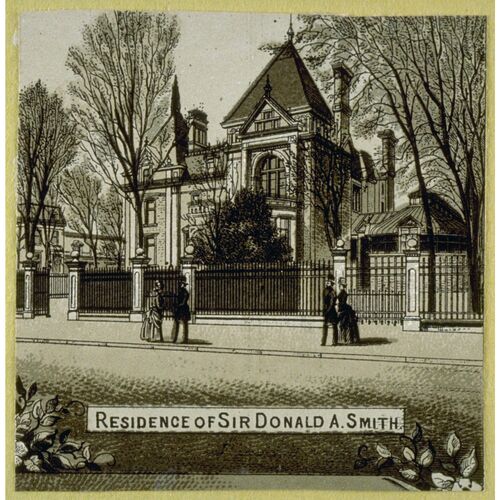

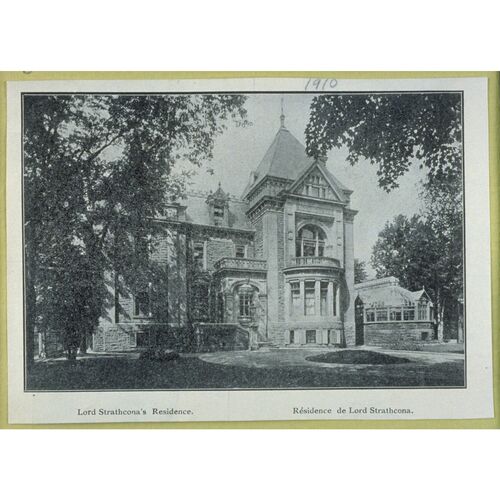

Smith earned a reputation for his lavish hospitality. In Manitoba he bought Silver Heights, formerly the residence of Lieutenant Governor Archibald. Dignitaries marvelled at his gardens and the Highland cattle he introduced to Canada. In Montreal he purchased a house on Dorchester Street (Boulevard René-Lévesque) which he expanded three times, transforming it into a brownstone mansion with an extensive conservatory and a staircase that reportedly cost $50,000. In 1895 he acquired Duncan McIntyre’s adjacent mansion to use as a guest house. In 1900 he commissioned Edward Maxwell* to add a conservatory to connect the two residences.

In his mansion he exhibited his collection of paintings and decorative arts. Smith acquired largely academic paintings, mostly those which had been included in exhibitions of the Paris Salon or the Royal Academy of Arts in London. In 1891 he was president of the Art Association of Montreal and his collection included works by Canadian artists Cornelius Krieghoff*, Otto Reinhold Jacobi*, John Arthur Fraser*, and Homer Ransford Watson*. He frequently invited visitors to see his collection; some, such as Lord Minto [Elliot], thought the “taste of the house appalling.” His mansion was also home to an enormous collection of objets d’art, including a large selection from the Orient. The contents of the house were valued at $550,000, $219,000 for the pictures and $210,000 for Japanese antiques. More than 100 paintings were donated to the Art Association of Montreal by his grandson in 1928.

Vice-regal and royal visitors frequently stayed in Smith’s houses. Both in London and in Montreal, he was one of the leaders of society. The Dominion Day event he hosted annually in London saw more than 1,000 Canadian and imperial dignitaries mingling in their finery at his expense. Indeed, the popularity of the event and the advantage of having a rich man in the high commissioner’s office may have been one reason why Laurier kept him there. Smith leased Knebworth House in Hertfordshire from Lord Lytton in 1899 and then purchased Debden Hall in Essex for £138,000 for use as a country house in 1903. In 1894 he had acquired a large estate in the Scottish Highlands, the site of the battle of Glencoe. There he built a spacious house equipped with electricity and central heating and employed a large staff. The glen would be acquired by the National Trust for Scotland in 1935. In 1904 Smith purchased Colonsay in the Inner Hebrides. He rarely visited the island but it became the favourite haunt of his reclusive family. He is credited with having stabilized its economy and with stemming its depopulation.

Smith’s personal tastes were plain: he preferred soda water to whisky, slept no more than six hours a night, and ate two simple meals per day, citing porridge as his favourite dish. His endurance was remarkable. Even as an octogenarian he outworked most men in his office.

Isabella Smith died in London on 12 Nov. 1913. Once she and her husband had left the fur trade outposts and moved into Winnipeg, Montreal, and then London society, she had endured derision and prejudice. She was privately dismissed as “a dour old hoddy doddy squaw,” and “our lady of the snows,” by the English aristocrats who accepted her hospitality. Smith and his daughter were protective of her reputation, and ensured under threat of legal action that passages regarding her native blood and her marital history were excised from several biographies. Smith died on 21 Jan. 1914 and was interred next to his wife in a magnificent mausoleum in London’s Highgate Cemetery. His entire estate was valued at $28,867,635. Since his early days in Labrador, he had provided financial support to his extended family. He established trusts worth more than $26,500,000 for his heirs and successors.

Already a prominent figure in Canadian life at the time of his appointment to London, he came to personify the image of success which the empire offered its citizens. His public image of a refined philanthropist was cultivated to mask a career which had included enormous hardship and occasional ruthlessness. His rapid rise within the HBC in the 1860s was propelled by good timing, effective salesmanship, and solid connections. He was the only one in his generation of HBC officers who combined experience with financial interests in Montreal and a seat in Ottawa. This unique combination enabled him to seize the opportunities which were presented and to advance the HBC’s interests and his own.

Smith initiated the HBC’s aggressive development of western transportation. He realized more clearly than his superiors that railways and land were the future for both the west and the company. Even when his interests multiplied, he never left the HBC, but he gave it sporadic attention for the final 30 years of his life. The last of the HBC’s imperial governors, he was also the only one in the company’s history to have risen from the lowest rank to the highest one. His 75-year association with the firm remains a record.

In his political career Smith demonstrated poor judgement bred by indifference to the political process. Never comfortable with the boundaries imposed by the electorate or the party, he was initially viewed as the member for the HBC, but he more properly became known as the member for his own interests. His peripheral involvement in politics none the less allowed him to play key roles in major events of Canadian parliamentary life. In contrast, he exhibited both daring and brilliance in his investments and business associations. As the individual who brought Hill and Stephen together, he provided the impetus for some of the most profitable railways in North America. Although he was rarely the leading member in business endeavours, he was involved in many of the major corporate successes of the 1880s and 1890s. An investor rather than a financier, he could be counted on for the twin virtues of a substantial investment and enormous patience. As chairman of several large financial and trust companies, he was an ideal figurehead, providing a well-recognized image of grace, success, and solidity.

In society Smith sought a large role and assumed his place with vigour. Never entirely at ease because of the stigmas attached to his wife’s native blood and the rumours about their marriage, he acquired all the trappings of Victorian society. Unlike many of his business colleagues on both sides of the Atlantic, however, he was generous with his ideas and time, and he was a donor of remarkable range and generosity. While he built no enduring business empire or charitable trusts, neither did he wield power to the detriment of people or continents. He remains the foremost example of the Canadian rags-to-riches story.

[Several published addresses by Donald Alexander Smith, including Imperialism and the unity of the empire . . . ([London?, 1900?]), can be found in the CIHM, Reg. In addition to the archival sources cited below, the files on Smith in the Bank of Montreal Arch. and the Canadian Pacific Arch. (Montreal) proved useful in the preparation of this biography. a.r.]

GA, M477, M5908. James Jerome Hill Reference Library (St Paul, Minn.), J. J. Hill papers. NA, MG 26, A; F; G; MG 29, A5; A6; A 11; A60; MG 30, D5; E86. National Library of Scotland (Edinburgh), Dept. of Manuscripts, mss 12446–587 (4th Earl of Minto, corr. and papers). Private arch., Skene, Edwards & Garson, W.S., D. A. Smith papers (National Reg. of Arch. (Scotland), Edinburgh, Survey no.1883), deed box A32 [researchers wishing to consult these papers should contact the National Reg. of Arch.]; Anthony Beckles Willson (Twickenham [London]), Family papers. PAM, HBCA, A.42/16–34; A.68/5–12. Yale Univ. Library, mss and Arch. Dept. (New Haven, Conn.), J. W. Sterling papers.

Gazette (Montreal), 14 Sept. 1888, 29 Jan. 1927, 7 May 1928. Globe, 1 Oct. 1911, 3 Feb. 1914. Monetary Times (Toronto), 8 Oct. 1880, 3 Feb. 1893. Montreal Daily Star, 13 Nov. 1913, 21 March 1941. Sun (New York), 5 Feb. 1914. World (Toronto), 22 Jan. 1914.

Christopher Armstrong and H. V. Nelles, Monopoly’s moment: the organization and regulation of Canadian utilities, 1830–1930 (Philadelphia, 1986). Janet Brooke, Discerning tastes: Montreal collectors, 1880–1900 (exhibition catalogue, Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, 1989). Can., House of Commons, Debates, 1871–72, 1875–78; Royal commission to inquire into a certain resolution moved by the Honourable Mr. Huntingdon, in Parliament, on April 2nd, 1873, relating to the Canadian Pacific Railway, Report (Ottawa, 1873). Canada Gazette, 9 Dec. 1871. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898 and 1912). L. C. Clark, “A history of the Conservative administrations, 1891 to 1896” (phd thesis, Univ. of Toronto, 1968). E. A. Collard, A very human store: a brief history of the Royal Trust Company, its first 75 years ([Montreal], 1975). T. A. B. Corley, A history of the Burmah Oil Company (2v., London, 1983). CPG, 1871–80, 1887–96. P. E. Crunican, “Father Lacombe’s strange mission: the Lacombe-Langevin correspondence on the Manitoba school question, 1895–96,” CCHA, Report, 26 (1959): 57–71. N. F. Davin, Strathcona Horse: speech . . . at Lansdowne Park . . . (Ottawa, 1900). J. A. Eagle, The Canadian Pacific Railway and the development of western Canada, 1896–1914 (Kingston, Ont., 1989). R. W. Ferrier, The history of the British Petroleum Company (2v. to date, New York and Cambridge, Eng., 1982– ). S. B. Frost, McGill University: for the advancement of learning (2v., Montreal, 1980–84). J. S. Galbraith, “Land policies of the Hudson’s Bay Company, 1870–1913,” CHR, 32 (1951): 1–21. Heather Gilbert, The life of Lord Mount Stephen . . . (2v., Aberdeen, Scot., 1965–77). Margaret Gillett, We walked very warily: a history of women at McGill (Montreal, 1981). Dolores Greenberg, Financiers and railroads, 1869–1889: a study of Morton, Bliss & Company (Cranbury, N.J., 1979). D. J. Hall, “Clifford Sifton: immigration and settlement policy, 1896–1905,” in The settlement of the west, ed. Howard Palmer (Calgary, 1977), 60–85. Lord Minto’s Canadian papers: a selection of the public and private papers of the fourth Earl of Minto, 1898–1904, ed. Paul Stevens and J. T. Saywell (2v., Toronto, 1981–83). Donna McDonald, Lord Strathcona: a biography of Donald Alexander Smith (Toronto and Oxford, 1996). Donald MacKay, The square mile: merchant princes of Montreal (Vancouver, 1987). R. C. Macleod, The NWMP and law enforcement, 1873–1905 (Toronto, 1976). Albro Martin, James J. Hill and the opening of the northwest (New York, 1976; repr., intro. W. T. White, St Paul, 1991). Don Morrow, “The Strathcona Trust in Ontario, 1911–1939,” Canadian Journal of Hist. of Sport and Physical Education (Windsor, Ont.,), 8 (1977), no.1 : 72–90. A. A. den Otter, “The Hudson’s Bay Company’s prairie transportation problem, 1870–85,” in The developing west: essays on Canadian history in honor of Lewis H. Thomas, ed. J. E. Foster (Edmonton, 1983), 25–47; “Transportation and transformation, the Hudson’s Bay Company, 1857–1885,” Great Plains Quarterly (Lincoln, Nebr.), 3 (1983): 171–85. J. G. Pyle, The life of James J. Hill (2v., Garden City, N.Y., 1917). Gerald Redmond, “Apart from the Trust Fund: some other contributions of Lord Strathcona to Canadian recreation and sport,” Canadian Journal of Hist. of Sport and Physical Education, 4 (1973), no.2: 59–69. W. R. Richmond, The life of Lord Strathcona (London, n.d.). L. W. Sawula, “Notes on the Strathcona Trust,” Canadian Journal of Hist. of Sport and Physical Education, 5 (1974), no.1: 56–61. Standard dict. of Canadian biog. (Roberts and Tunnell). G. F. G. Stanley, “The fur trade party,” Beaver, outfit 284 (Sept. 1953): 35–39; (Dec. 1953): 21–25. Beckles Willson, The life of Lord Strathcona and Mount Royal, g.c.m.g., g.c.v.o. (2v., Boston and New York, 1915).

Cite This Article

Alexander Reford, “SMITH, DONALD ALEXANDER, 1st Baron STRATHCONA and MOUNT ROYAL,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 29, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/smith_donald_alexander_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/smith_donald_alexander_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | Alexander Reford |

| Title of Article: | SMITH, DONALD ALEXANDER, 1st Baron STRATHCONA and MOUNT ROYAL |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | March 29, 2025 |