Source: Link

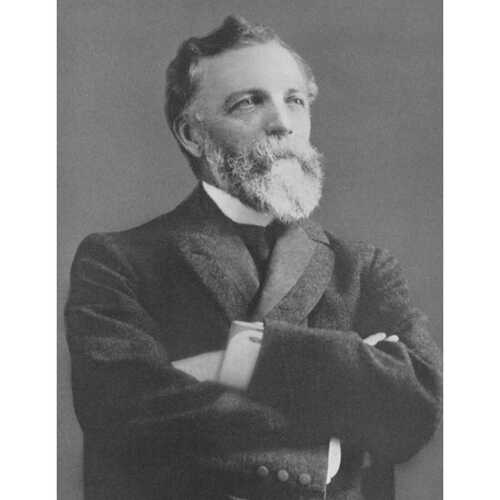

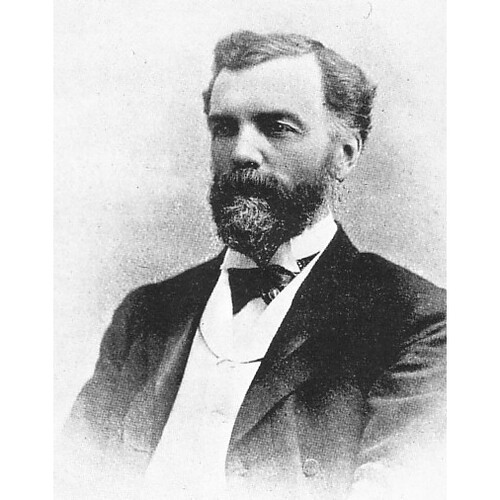

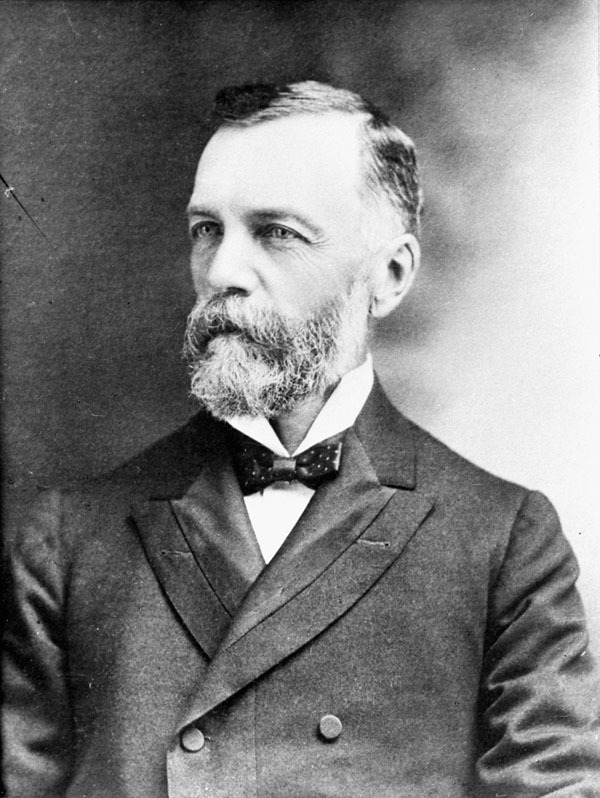

TARTE, JOSEPH-ISRAËL, notary, journalist, newspaper owner, and politician; b. 11 Jan. 1848 in Lanoraie, Lower Canada, son of Joseph Tarte, a farmer and businessman, and Louise Robillard; m. first 23 Nov. 1868 Georgiana Sylvestre in L’Assomption, Que., and they had six children; m. secondly 23 Feb. 1905, in Ottawa, Marie-Emma Laurencelle, widow of Narcisse Turcot, and they had one daughter; d. 18 Dec. 1907 in Montreal and was buried there three days later in Notre-Dame-des-Neiges cemetery.

Little is known about Joseph-Israël Tarte’s childhood. His father died in 1851, and he is thought to have attended school in Lanoraie. Working the family farm herself, his mother supported her three children by dint of drudgery and privation. Tarte would later say that she taught him to love the religion of his ancestors and “also that supremely beautiful religion: work.” In 1860 Tarte entered the Collège de L’Assomption. When he completed his sixth year (Rhetoric) in 1865, he won two prizes for French and two for Latin. He did one year of the Philosophy program and then left the college. A school friend described him as a hard worker, an “intellect receptive to everything,” and a “keen mind.”

Tarte was articled in L’Assomption to Louis Archambeault*, president of the Montreal district Board of Notaries and from 1867 commissioner of agriculture and public works in the cabinet of Pierre-Joseph-Olivier Chauveau*. There he discovered the life of politics and became firmly convinced that confederation was a necessary, acceptable, and inviolable compromise. His taste for argument and his need to understand and persuade led him into journalism. He was admitted to the profession of notary on 3 May 1871. At the time he was living in his father-in-law’s home and had a child a few months old. He opened his office in Archambeault’s premises at L’Assomption and, with his tacit agreement, set about providing the region with a Conservative newspaper that would undermine the ultramontanist influence of Le Nouveau Monde. At the end of September 1872 Tarte began to write for La Gazette de Joliette, a moderate, balanced, and cautious Conservative weekly whose columns, he claimed, “are in good taste and always high-minded.” The paper would thenceforth serve the counties of Joliette and L’Assomption. This endeavour was only a stepping-stone. In the spring of 1874 Tarte moved to Saint-Lin and in June he launched Les Laurentides, a biweekly of which he was editor and Jean-Baptiste Delongchamps was manager. He was already putting forward an idea he would champion for the rest of his life: the need for a protective tariff to encourage the industrialization of the country. By mid July he was ardently defending Archambeault and the Conservatives who were implicated in the Tanneries scandal. His articles, which were reprinted by the major newspapers, created a sensation. Although Premier Gédéon Ouimet had to resign, the party members involved in the affair emerged with their honour unsullied, partly thanks to Tarte. Grateful Conservatives, eager to enlist a man of such remarkable talent in their cause, invited him to join the staff of Le Canadien in Quebec City.

Tarte arrived there in October 1874, aged 26. He was made assistant editor, and earned $300 a year, including lodging. He quickly became recognized as the best journalist of his generation. Despite the fame of his polemics, his journalistic methods are still not well known, and thus the role he played in the early development of the popular press is not clear. With funds advanced by the Conservative party, he acquired Le Canadien and its weekly edition, Le Cultivateur, on 12 June 1875. On 17 July he went into partnership with Louis-Georges Desjardins. Tarte dealt with editorial matters, with the bookkeeping to some extent, and with wheedling out of Hector-Louis Langevin and Thomas McGreevy* the printing contracts and donations that enabled Le Canadien to survive financially. He attempted to give a new lease on life to the paper, which reached a circulation of 1,850 in 1875 and 1876. But the owners were short of capital to pay off accumulated debts and undertake essential improvements. Threatened with the seizure of his property, Tarte appealed to Langevin, who intervened behind the scenes. None the less, Tarte was still burdened with debt and had to divest himself of his shares. On 8 Feb. 1877 Desjardins became sole proprietor of the two newspapers. Joseph-Norbert Duquet was made manager of Le Canadien and Tarte stayed on as editor. These were difficult times. Probably because of the depression, circulation dropped to 500. In March 1880 there was another change: L. J. Demers et Frère bought the two papers. Tarte became editor-in-chief, and the editorial staff gradually expanded, an assistant editor being added in 1882 and another editor and a reporter in 1883. Circulation then reached 2,500. The increase in staff explains why, when Louis-Joseph Demers and his brother bought L’Événement on 22 May 1883, Tarte was able to assume the position of editor-in-chief of that paper and still keep an eye on the content of Le Canadien and Le Cultivateur.

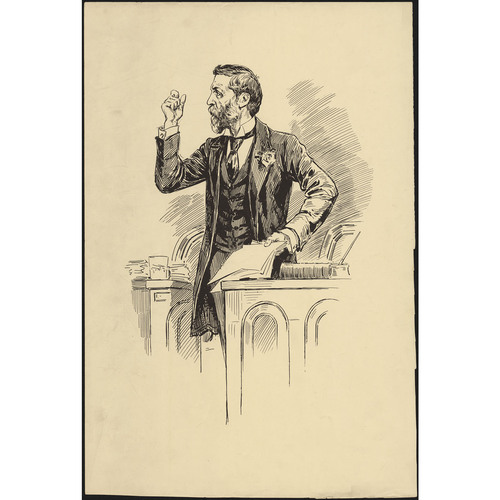

For Langevin, who was the acknowledged leader of the Quebec Conservatives after the death of Sir George-Étienne Cartier*, Tarte served as conscience. He was responsible for the political and ideological line adopted by Conservative newspapers in the Quebec region. A tireless worker with a restless nature, a talent for digging out news, and the memory of an elephant, he proved a redoubtable polemicist. He had clear-cut ideas about his profession and the role of the press. “First of all,” he wrote to Langevin in August 1880, “I contend that a journalist who seeks popularity is not worthy of his profession, for he follows currents of public opinion instead of leading them. In the second place, I maintain that a convinced writer is not a free man, but must devote himself unreservedly to the cause he loves and for which he fights.” He wrote vigorously, with short sentences, a direct tone, and paragraphs that hit like a sledge-hammer. He liked to turn out daily instalments of reports in which he showed the ins and outs of a question, argued and queried, implicated and insinuated, and finally demolished his opponent. Tarte’s contemporaries left a picture of him as a man with a hectic life, working at L’Événement by day and Le Canadien by night. This description needs some qualification. Around 1878 Tarte bought a farm at Sillery, “equipped with all the latest implements and machines,” and he and his brother worked it. According to Charles-Edmond Rouleau, a journalist at Le Canadien, Tarte seldom went to the office. He wrote his articles at home and more often than not sent his instructions by messenger.

From the time of his arrival at Le Canadien, Tarte had been attacking Langevin’s rival, Joseph-Édouard Cauchon*, who was advocating a union of moderate Liberals and Conservatives under his own leadership. This memorable duel was to continue for several years. Seeking to preserve the unity of the Conservative party, which was caught between the ultramontanists and the moderate Liberals, Tarte took advantage of the burial of the excommunicated Joseph Guibord* in November 1874 to suggest that Liberals were anticlericals. He also used Louis Riel*’s banishment in February 1875 to be more nationalistic than the ultramontanists. Then, in the spring, he did an about-face. Claiming to have been influenced by reading material reputedly suggested to him by some priests, and doubtless foreseeing that no political party could remain in power without substantial support from the clergy, he adopted the ultramontanist views that underlay clerical interference in elections. In a pamphlet entitled Le clergé, ses droits, nos devoirs, published in 1880, Tarte spelled out the premises of his ultramontanism. The clergy is the father of the French Canadian nation and alone can guide it along the paths that will ensure its survival. The nation must remain united in a single faith, a single form of worship, a single obedience to the teachings of Rome, and a single willingness to give “a large place – the largest – to the Catholic hierarchy in the organization of our society.” Until March 1883 Tarte did not deviate from this credo. According to Thomas Chapais*, the editor of Le Courrier du Canada (Québec), “Every day, in the columns of Le Canadien, Israel slays a new sacrificial offering of Liberals, Gallicans, freemasons, and sectarian devotees of modernism.”

After the provincial election of the summer of 1875, Tarte, who had been one of the Conservatives’ main organizers in the Quebec region, emerged as Langevin’s lieutenant. On his initiative the clergy routinely interfered in elections. He ran against Cauchon in a federal by-election in Quebec Centre on 27 Dec. 1875 but withdrew at the last minute, convinced he would be defeated. He then went to Charlevoix to support Langevin, who was making a desperate effort to win re-election to the commons. William Evan Price* provided the funds and Tarte led the Conservative troops with great enthusiasm. He proved a peerless strategist, relying on personal contacts, publicity, and a steady flow of propaganda. He flooded the riding with leaflets appealing to popular prejudices, circulated the wildest rumours, and personally visited the house of every parish priest. Langevin was elected on 22 Jan. 1876, but his opponent, Pierre-Alexis Tremblay*, challenged the results on grounds of undue influence. Judge Adolphe-Basile Routhier* heard the case in La Malbaie during the summer. Tarte followed it closely. Every day he sent passionate, indeed violent, articles to Le Canadien, which twice led to his being convicted of contempt of court. In defence of clerical interference, he queried: “Is voting an act that can be good or evil?” He concluded in the affirmative and maintained that it was therefore the duty of the clergy to “educate people’s conscience.” Routhier declared the election valid, but his ruling was reversed by the Supreme Court of Canada on 28 Feb. 1877. Meanwhile, on 22 February, Tarte had won a seat in the Quebec Legislative Assembly. Using more discreetly the methods he had perfected in Charlevoix, and benefiting from the support of Bishop Jean Langevin* of Rimouski, he ran in a by-election in Bonaventure riding. The campaign was described by Le Journal de Québec of 24 March as “organized hypocrisy.” After two years of electoral battles, Tarte had a reputation as the great protector of the clergy, even though he had to make a public apology in April for insinuating that Archbishop Elzéar-Alexandre Taschereau* of Quebec, a man of liberal philosophical bent, had brought pressure to bear on his brother Jean-Thomas*, a justice of the Supreme Court, to have Routhier’s decision quashed.

Premier Charles Boucher* de Boucherville did not propose to open the legislature until December; Tarte had plenty of time to devote to his favourite game, journalism. He roundly berated Joseph-Adolphe Chapleau*, the rising star of the party and Langevin’s rival, for making Cauchon’s dream of a merger of parties his own. He kept a close watch on the comings and goings of the apostolic delegate, Bishop George Conroy*, whom he considered too indulgent towards the Liberals. In November he became deeply involved in a federal by-election in Quebec East, where Wilfrid Laurier* was running. When the assembly convened, Tarte was given the honour of replying to the speech from the throne, and he turned this innocuous ritual into a violent attack on the Liberals. The dismissal of Boucher de Boucherville by Lieutenant Governor Luc Letellier* de Saint-Just on 2 March 1878 was tantamount to a declaration of war on the Conservatives. Le Canadien called for the barricades to be manned: “Let the people take the cause of their liberties into their own hands.” Tarte harangued the crowds at public meetings. This rabble-rousing continued until election day, 1 May. The Liberals, led by Henri-Gustave Joly, won the same number of seats as the Conservatives; Tarte was returned in Bonaventure. He enjoyed no respite, however. He was assigned to organize the Conservative campaign in the Quebec region for the federal election of 17 Sept. 1878. Le Canadien supported the protectionist policy of Sir John A. Macdonald* and demanded the dismissal of the lieutenant governor for exceeding his authority. The Conservatives won a smashing victory.

Foreseeing Chapleau’s meteoric rise to the leadership of the Quebec Conservative party, Tarte tried to effect a reconciliation with him while preserving his ties with Langevin and the ultramontanists. In veiled fashion he took up Chapleau’s cherished idea of uniting the moderates of both parties. He plotted with Chapleau and with Louis-Adélard Senécal* to have Letellier de Saint-Just dismissed by Governor General Lord Lorne [Campbell*]. Also with Chapleau, he confronted the Liberal Honoré Mercier* at public meetings. Then, when the session of the provincial legislature opened on 19 June 1879, Tarte began his campaign there and in Le Canadien to undermine the Joly government, which had a majority of only four. He made serious charges of corruption, alleging the inflation of invoices, fraudulent awarding of contracts, bribery, and the transfer of a piece of property to Hammond Gowen, the premier’s brother-in-law. The government was shaken. The final blows fell when the lieutenant governor was dismissed on 25 July and the Legislative Council, which was largely Conservative, refused to vote supply on 27 August. Joly tendered his resignation to the new lieutenant governor, Théodore Robitaille*, on 30 October and Chapleau became premier the following day. He appointed a cabinet of moderates chosen from the ranks of Conservatives, Liberals, and ultramontanists. Tarte, who considered himself a veteran and who had paved the way for Chapleau, resented being passed over.

Left out of the cabinet, Tarte undertook to thwart Chapleau’s plan, which was to reunite the Conservative forces by isolating the ultramontanists and then to succeed Langevin as federal leader. Tarte maintained his posture as the champion of the ultramontanists. In 1880 and 1881 he exposed negotiations for a coalition between Mercier and Chapleau; he denounced the inside dealings characteristic of Chapleau’s government and was among the ultramontanists who pressed the premier to recognize certain ecclesiastical immunities. His opposition to Chapleau reached a peak in March 1882, when he worked with the Liberals in holding a series of public meetings to prevent the sale of the eastern section of the Quebec, Montreal, Ottawa and Occidental Railway, a transaction which, according to Tarte, would be detrimental to the interests of Quebec City and facilitate “boodling.” But Chapleau overcame all obstacles and on 29 July Macdonald appointed him secretary of state at Ottawa. His successor in Quebec, Joseph-Alfred Mousseau*, formed a cabinet from which the ultramontanists were excluded.

Tarte now had some difficult decisions to make. Because warnings from Rome in September 1881 against clerical interference had somewhat disconcerted him, he had not run in the December election. Langevin, his patron, was finding it harder and harder to maintain his leadership of the Quebec Conservatives. The future, it seemed, might belong to Chapleau. In the autumn of 1882 Tarte was in Paris as a guest of Senécal, along with Chapleau, Arthur Dansereau*, and Alexandre Lacoste*. He returned in November still loyal to Langevin but in a mood to abandon the ultramontanists. He was by now convinced that the unity of the Conservative party and its ability to defend French Canadian interests in Ottawa required good relations between Langevin and Chapleau and the defeat of the ultramontanists. In the spring of 1883 he urged the latter to submit to the ruling of the Sacred Congregation of Propaganda with regard to the Université Laval [see Taschereau]. In September he supported Mousseau in a by-election in Jacques-Cartier. He resigned from the Cercle Catholique de Québec [see Jean-Étienne Landry*] and denounced the Castors who would not accept Rome’s decision about the Montreal School of Medicine and Surgery [see Thomas-Edmond d’Odet* d’Orsonnens]. “You embody revolt in religious society and disorder in civil society,” he wrote in Le Canadien on 22 August. From then on, he devoted himself to destroying the ultramontanists.

Tarte had become powerful. His pen kept him in the public eye. He associated with the leading lights of the Conservative party. He had access to Senécal and McGreevy, who were major financial backers for election campaigns, and he had contacts among the Liberals. He was involved in many schemes and knew them all inside out. Power meant more to him than money, which he used, not for personal gain, but in the interests of his party. He again took up, on his own, the cause of uniting moderate Conservatives and Liberals in a single party. But the Riel affair distracted him for a time and revealed his ambivalence: an unalterable attachment to Canadian confederation that had to be reconciled with a firm resolve to ensure that French Canadians flourished. In April 1885 he supported the dispatch of the 9th Battalion Volunteer Militia Rifles to put down the Métis rebels, but he protested against the way in which the court that would try Riel was constituted. He flirted briefly with the nationalist movement that would give rise to Mercier’s Parti National, and then left it, fearing Quebec might become isolated within confederation. A strong Conservative party within a united Canada became his theme.

Events followed hard upon one another and Tarte, walking a fine line, kept shifting from side to side. In June 1886, in his capacity as organizer and treasurer of the Conservative party, he campaigned against Mercier. Mercier was in the process of creating for himself an organization of French Canadians that brought together people of diverse political leanings. With Thomas Chapais of Le Courrier du Canada, Tarte endeavoured to drive a wedge between him and the ultramontanists. Tarte was an organizer in the federal election of 22 Feb. 1887, and in Le Canadien he absolved Chapleau of blame for not resigning his office in Ottawa during the Riel affair. In May he made an attempt to get Langevin appointed lieutenant governor in order to pave the way for Chapleau to become Conservative leader. But, with Macdonald’s support, Langevin held onto his cabinet post, even though his popularity was plummeting and he proved useless in the struggle against Mercier. In fact, Tarte had a certain admiration for Mercier, and had it not been for the obstructive tactics of the Parti National’s Castors, especially Jules-Paul Tardivel, he might have gone over to him. Yet whatever ambivalence he experienced, Tarte was an effective voice of opposition outside parliament in Le Canadien and L’Événement, of which he was editor. His extreme language was typical of the time. “Violator of the constitution,” “embezzler of public funds,” and “corrupter of the people” were among the epithets in his usual vocabulary. He supported Mercier’s policy of modernizing the means of transportation and methods of colonization but spoke out against his ostentatious and needlessly provocative attitude, and especially the inter-provincial conference of 1887 which threatened to undermine Canadian unity.

Tarte became more and more convinced that Mercier was in danger of cutting Quebec off from the rest of the country and that Langevin, powerless, isolated, and tied to the anglophone right wing of the Conservative party, was incapable of unifying and representing the mainstream conservative forces in the province. Because he believed in a strong Quebec in a united Canada, Tarte brought matters to a head. He chose to back Chapleau. His basic strategy was to denounce the system of patronage which McGreevy used on behalf of both Langevin and Mercier. McGreevy’s downfall, he supposed, would force Langevin to withdraw from active politics and cause Mercier to adopt a policy of caution. He wanted to settle the affair quietly within the party, but Macdonald refused to pay serious attention to the file that Tarte gave him in March 1890. He thought there was more to be gained by letting Langevin, Chapleau, and Sir Adolphe-Philippe Caron fight it out for the leadership in Quebec. Tarte had other plans, however, especially since his purchase of Le Canadien and Le Cultivateur in September 1889 had given him a certain independence from the party. On 18 April he published an article on McGreevy in Le Canadien; it was followed by others, which led McGreevy to sue him for libel. Still hoping to find supporters in the Conservative party (possibly Caron), Tarte replied in the fall with “Les coulisses du McGreevéisme,” a series of articles on McGreevy’s activities behind the scenes. He then handed the entire matter over to Laurier, the leader of the opposition in the commons, asking him to defend Tarte in the action that McGreevy was bringing against him, but all the while maintaining that he himself was still a Conservative. According to lawyer Antonio Perrault*, Laurier said: “Tarte, why don’t you come with us? You are underrated in your party.” Tarte resisted this invitation. In the federal election of March 1891 he ran as an independent in Montmorency, but Laurier had Charles Langelier* organize his campaign. The Liberals gained a majority of 11 seats in Quebec, but Macdonald still won the election. When the commons convened in April, Tarte expressed indignation at so much bribery. On 11 May he made accusations against McGreevy that led to Langevin’s resignation on 11 August. The Conservatives responded by exposing the Baie des Chaleurs Railway scandal, in which the Mercier administration was implicated. Prime Minister John Joseph Caldwell Abbott*, who had recently succeeded Macdonald, refused to give Chapleau a senior cabinet post, which would have made him the leader of the Quebec Conservatives. The party in Quebec was, in a sense, decapitated. Tarte predicted that “the French Canadian element in the Conservative party will not consent to be dominated and kept in leading-strings by its allies in the other provinces.”

Tarte came out of the McGreevy affair financially ruined – he could no longer pay Louis-Joseph Demers the printing costs for his newspapers. Expelled from the Conservative party and isolated, Tarte needed friends and he accepted Laurier’s invitation. At the beginning of December he moved to Montreal, which was becoming more and more the epicentre of ideological, political, and social movements. It was a new departure, one in which he demonstrated extraordinary strength of character, energy, and intelligence. Because of irregularities he was alleged to have committed during the election campaign, he was forced to give up his Montmorency seat in the commons. He used Le Canadien to denounce, on constitutional grounds, the conduct of his only real friend, Lieutenant Governor Auguste-Réal Angers*, for having dismissed Mercier from office. He attacked clerical interference in elections and levelled accusations against former friends, including cabinet minister Sir Adolphe-Philippe Caron, who was reportedly taking commissions on public contracts and on subsidies to railway companies.

In July 1892 the political scene was rocked by a Privy Council decision that upheld the Manitoba law abolishing the province’s system of Catholic and Protestant public schools [see The Manitoba School Question]. Political parties had to take a stand. The Conservatives were divided on the issue of remedial legislation. Lethargic by nature and seeking a policy that would win the support of both extremes, Laurier took refuge in a cautious wait-and-see attitude. Tarte, who had become his éminence grise and was soon elevated to chief organizer, set to work to rally the people of Quebec behind the Liberal leader. A federal by-election in L’Islet in January 1893, in which Tarte was returned to the House of Commons, served as a testing ground that revealed the strategy. Tarte promised that the Liberals would adapt their tariff policy to the needs of farmers, take legal action against Conservatives who had misappropriated public funds, restore order to the administration of justice, and, above all, ensure that the Catholic minority in Manitoba received just treatment. He portrayed the Liberals as the defenders of morality, of farmers, of the oppressed, and of French Canadian nationalism. At this time he allowed Le Canadien to die a natural death. A newspaper of ideas, a fighting paper written for an intellectual and political élite, it was no longer suitable for the mass of urban readers, who looked for brief news items and sensationalism. Instead he used Le Cultivateur and his column as parliamentary correspondent for L’Électeur (Québec) to denounce corrupt Conservatives who were too cowardly to defend the interests of Catholics and French Canadians, and to condemn the ageing Archbishop Alexandre-Antonin Taché* of St Boniface, who had lacked the courage before the 1891 election to insist on federal disallowance of the Manitoba law. Tarte’s strategy was aimed at hastening the disintegration of the Conservative party in Quebec. He employed two tactics. He worked to bring the moderate Conservatives into Laurier’s camp, and he attempted to convince the electorate that the school question was a political one which transcended the opposing religious interests and could therefore be settled only through a compromise effected by politicians. Between sessions Tarte worked at the grass roots level, taking part in by-elections, accompanying Laurier when he toured the province, and making sure that well-run Liberal organizations emerged in each riding. His struggle with the bishops intensified.

On 9 May 1894 Archbishop Joseph-Thomas Duhamel of Ottawa presented Governor General Lord Aberdeen [Hamilton-Gordon*] with a petition signed by the Canadian bishops which demanded the disallowance of sectarian laws and the passage of remedial legislation. The cabinet issued an order in council on 21 March 1895, asking Manitoba to restore the rights and privileges of the Catholic minority. On 24 Jan. 1896 Tarte called for an inquiry into the school question, claiming that the proposed remedy was insufficient. He crossed swords with Bishop Michel-Thomas Labrecque* of Chicoutimi and theologian Louis-Adolphe Pâquet*, who were intent on usurping the legislators’ role. In the federal election of 1896 he ran in Beauharnois, where the Montreal Cotton Company reigned supreme, and he promised the protective tariff would be retained. Since strong Conservative leadership in the campaign was lacking, the bishops – especially Louis-François Laflèche* – became even more involved in politics. Their efforts were wasted. On 23 June the voters brought Laurier to power. Tarte was defeated in Beauharnois, but would win a seat on 3 August in Saint-Jean–Iberville.

On 13 July 1896 Tarte was appointed minister of public works. Neither the old Bleus nor the old Rouges would forgive him for his betrayal and cynicism. As one of the key men in cabinet, he had a special assignment: to strengthen Liberal foundations in the province of Quebec. He was methodical and meticulous in carrying out his duties. He had a hand in every measure that concerned French Canadians. As political organizer for the province, he was also in charge of patronage and was one of Laurier’s trusted advisers on religious matters. He suggested to the prime minister that Abbé Jean-Baptiste Proulx and Gustave-Adolphe Drolet, a former Papal Zouave, be sent to Rome to argue against clerical interference in elections and to defend Laurier’s position in the Manitoba school question. In the fall Tarte and Henri Bourassa* went to Winnipeg to negotiate a settlement of the school question with Thomas Greenway, Joseph Martin*, and Clifford Sifton*. The talks were conducted without the participation of Taché’s successor, Archbishop Adélard Langevin*, who was considered impulsive and intransigent. The agreement, published on 19 November, fell far short of the Conservatives’ remedial legislation. It did not restore the dual system of schools, but stipulated instead that at the request of a set number of parents the public schools could provide a half hour of religious instruction daily, engage Catholic administrators and teachers, and teach in English and another language, for example French.

When he returned from the west, Tarte turned his attention to the forthcoming provincial election campaign in Quebec. On 4 Feb. 1897 he bought La Patrie with party funds and turned it over to his sons Louis-Joseph and Eugène. He took various steps to speed up the improvement of’ the Laurentian route for wheat being shipped to Europe from the west. The Soulanges Canal was built to replace the Beauharnois Canal; the channel between Quebec and Montreal was deepened; port facilities were repaired and enlarged; and the great eastern Canadian shipyards at Sorel were set up. Nor did he neglect the needs of the Maritime provinces and British Columbia. He undertook to provide a rapid link between Liverpool, England, and Montreal and to connect the Intercolonial and the Grand Trunk by the Drummond County Railway (which was owned by James Naismith Greenshields*, the lawyer who, oddly enough, had paid the $20,000 for the purchase of La Patrie). He considered using an ice-breaker to keep the St Lawrence open to shipping all year round. These multifarious activities paid dividends at election time: Montrealers were happy about the work done on the river and responded with time and money.

But Tarte was not a dyed-in-the-wool partisan. He was first and foremost a man with his own concept of Canada as a modern country, one that respected religious freedom, was concerned for the rights of French Canadians, and was independent in international affairs, though still a member of the British empire. He had frequent disagreements with Laurier and the party leadership. On 9 Oct. 1899 La Patrie opposed the sending of troops to the Transvaal: Tarte was against participation in imperial wars without fair representation in an imperial parliament. At his insistence, Laurier obtained an order in council stipulating that the sending of volunteers would not constitute a precedent. Tarte agreed to the dispatch of a second contingent only because he was afraid the Conservatives might win the next election if the Liberals refused to send it. His stand isolated him from the rest of the cabinet. In the spring of 1900 his pro-French attitudes and speeches as chief commissioner for Canada at the universal exposition in Paris hastened the deterioration of his relations with English-speaking Canadians. When he returned on 17 August, he declared that French Canadians, though loyal subjects of the queen, would never renounce their culture. He then plunged into the election campaign as a candidate in the Montreal riding of Sainte-Marie. Re-elected once more, Tarte busied himself in the Department of Public Works, where his plan to modernize transportation – and construct the Georgian Bay canal at an estimated cost of $30 million – was raised to the status of a national project. It was an expression of a Canadian nationalism painfully seeking its way between the economic imperialism of the United States and the political imperialism of Great Britain. But public opinion was divided on the issue of “Canada for Canadians.” On the strength of support from some manufacturers, Tarte launched a campaign for higher tariffs in the summer of 1902 while Laurier was visiting England. He held some 100 public meetings in Quebec, Ontario, and the Maritime provinces. When Laurier returned in October, he demanded Tarte’s resignation for having breached cabinet solidarity. Tarte kept his seat in the House of Commons as well as ownership of La Patrie.

Tarte had not yet broken with the Liberal party. But Premier Simon-Napoléon Parent* of Quebec, who began sending government printing contracts to the new Liberal organ Le Canada instead of to La Patrie, antagonized him. La Patrie attacked the Parent government’s policies on agriculture and forestry. By May 1903 Tarte was part of the Conservative opposition in the House of Commons. He was one of the few francophones to endorse the strengthening of the imperial preferential tariff proposed by Joseph Chamberlain, the British colonial secretary. He may have seen in it the outline of a political program that the Conservative party could support. From then on, with the support of his former enemies Louis-Philippe Pelletier* and Thomas Chase-Casgrain*, Tarte began manœuvring to take the place of Frederick Debartzch Monk* as Conservative leader in the province of Quebec and right-hand man of the federal Conservative leader, Robert Laird Borden*. He did not call himself a Conservative, but a protectionist. In January 1904 Monk resigned, deeply hurt by Tarte’s machinations. Tarte became Conservative organizer in the Hochelaga and Saint-Jacques by-elections, but did not run in the general election that year.

The adventure with the Conservatives was brief. Tarte’s arrival spread discord in the party’s ranks. In 1905 he withdrew from active politics to become an ordinary journalist. To the amazement of both friends and enemies, his “Lettres de la capitale,” published in La Patrie, supported Laurier’s position on the school question in Saskatchewan and Alberta. But his strength was failing. He felt the need for long periods of rest at his summer home in Boucherville. His last article, dated 18 July 1907, was prophetic. He saw that Bourassa, in alliance with Joseph-Mathias Tellier* and Pierre-Évariste Leblanc*, might sweep Premier Lomer Gouin* of Quebec out of office and endanger Laurier. Tarte died on 18 Dec. 1907 at the age of 59, leaving a $50,000 insurance policy that his sons had been paying for, a house on Square Saint-Louis, and his Boucherville home.

Small in stature, excitable and impressionable by nature, Tarte had a constantly active imagination, an inability to concentrate on deep deliberation or patient research, and an insatiable need to work. Brave to the point of recklessness, he concealed a generous heart behind a gruff exterior, a sometimes touchy temperament, and an often abrupt manner. For 30 years he was involved in all the political battles and he was active in most of the political parties of his time. His about-faces and “betrayals” disconcerted his contemporaries. They agreed as to his intelligence and passion for work, but they never reached a consensus on his political dealings. That he was given the nickname Judas Iscariot shows the scorn in which he was held by some people. Nevertheless, in his peregrinations which had such a powerful influence on men and parties, certain constants emerge. Throughout his life Tarte was a practising and devout Catholic. He went to confession and took communion regularly and said his rosary every day. He regarded “earthly life as a passage towards a better future life, and work as the basis of all success.” He had a lofty and exacting view of politics – he often lived in poverty and never enjoyed more than decent comfort. He always refused to sit on company boards of directors. He had a deep understanding of parliamentary government and people and, as a practical man who put morals and politics into separate compartments, he knew that patronage could be good as well as bad. He was imbued with the idea that a Canadian nation might be born “which would be something other than the fusion within the Anglo-Saxon soul” of French Canadian national culture. The four elements that made him what he was – a francophone, Catholic, Canadian, and British subject – sometimes led him, in politics, to try to square the circle. Whether because he had been orphaned at an early age or because he lived at a time of great collective insecurity, Tarte was always looking for a leader who could safeguard his French Canadian identity in a united Canada within an imperial federation. In his view, this ideal transcended men and parties. He used to say that he had retained from Sir Louis-Hippolyte La Fontaine* and from Cartier the idea that wise compromise and sensible conciliation are the guarantee of political equality and the enjoyment of certain rights.

Joseph-Israël Tarte is the author of Aux contribuables du comté de L’Islet (s.l., [1893?]); D[i]lapidation des fonds publics; $12,000 pour la famille Joly! Job honteux! (s.l., s.d.); 1892, procès Mercier: les causes qui l’ont provoqué, quelques faits pour l’histoire (Montréal, 1892); Les leçons de l’histoire pour les électeurs de la province de Québec; le programme libéral réfuté ([Québec, 1879]); Lettres à l’hon. H. L. Langevin, membre du cabinet de la Puissance du Canada (Québec, 1880); and La prétendue conférence; les périls de la souveraineté des provinces; l’autonomie canadienne est notre sauvegarde (Québec, 1889).

AC, Montréal, État civil, Catholiques, Cimetière Notre-Dame-des-Neiges (Montréal), 21 déc. 1907. ANQ-M, CE5-4, 11 janv. 1848; CE5-14, 23 nov. 1868. ANQ-Q, P-134, 23; E53/96; T11-1/28, nos.1698 (1875), 1936 (1877); 113, no.12 (1892); 553, no.758 (1883); 579, no.828 (1880); 831, no.1300 (1890); 889, no.1426 (1897); 891, no.1713 (1875); 959, no.1572 (1876); 968, no.1590 (1876); 1194, no.2186 (1896); 1265, no.2440 (1892); 1286, no.2540 (1890). AO, RG 80-5, no.1905-005588. NA, MG 27, II, D16; RG 31, C1, 1861, Lanoraie, Qué. (mfm. at ANQ-Q); C1, 1871, L’Assomption, Qué. (mfm. at ANQ-Q). Le Canadien, 9 déc. 1891. Gazette (Montreal), 19 Dec. 1907. La Gazette de Joliette, 26 sept. 1872, 19 mars 1874. Globe, 19 Dec. 1907. Les Laurentides (Saint-Lin [Laurentides], Qué.), 29 sept. 1874. La Patrie, 21 juin 1904; 18–20 déc. 1907. Le Soleil, 19 déc. 1907.

Agenda historique du collège de L’Assomption pour le 150e, 1832–1833/1982–1983, Réjean Olivier, compil. (L’Assomption, 1982). François Béland, “F. D. Monk, le Parti conservateur fédéral et l’idée d’un Canada pour les Canadiens (1896–1914)” (thèse de ma, univ. Laval, Québec, 1986). Réal Bélanger, Wifrid Laurier; quand la politique devient passion (Québec et Montréal, 1986). R. J. Belliveau, “Joseph Israël Tarte and French Canadian nationalism, 1876–1896” (des thesis, Univ. de Montréal, 1970). Fernand Boulet, Traditions du collège de L’Assomption au cours de ses 150 ans d’existence, 1832–1833/1982–1983, Réjean Olivier, édit. (Joliette, Qué., 1983). Can., House of Commons, Debates, 1897. Thomas Chapais, Judas Iscariote Tarte; sa carrière politique d’après divers auteurs (s.l., 1903); Mélanges de polémique et d’études religieuses, politiques et littéraires (Québec, 1905). Béatrice Chassé, “L’affaire Casault–Langevin” (thèse de des, univ. Laval, 1965). [C.-A. Cornellier], Autour d’une carrière politique, Joseph-Israël Tarte, 1880–1897, dix-sept ans de contradictions (s.l., s.d.). J. Desjardins, Guide parl. Directories, Montreal, 1892–94; Quebec, 1874–1900. DOLQ, vol.1. Anastase Forget, Histoire du collège de L’Assomption; 1833 – un siècle – 1933 (Montréal, [1933]). J. Hamelin et al., La presse québécoise, vols.1–3. Hormidas Jeannotte, Communication par H. Jeannotte, ecr., m.p., à ses électeurs du comté de L’Assomption; Tarte contre Laurier (Montréal, 1894). Joseph-Israël Tarte, son pedigree politique et celui de . . . son illustre famille . . . (s.l., s.d.). Lanoraie il y a cent ans ([Lanoraie, 1983]). L. L. LaPierre, “Joseph Israel Tarte; relations between the French Canadian episcopacy and a French Canadian politician (1874–1896),” CCHA Report, 25 (1958): 23–38; “Politics, race and religion in French Canada: Joseph Israël Tarte” (phd thesis, Univ. of Toronto, 1962). Les Libéraux honnêtes répudient M. Mercier; ce que M. Tarte écrivait en 1887 et ’90 . . . (s.l., s.d.). Séraphin Marion, “Mgr Bruchési, Mgr Rozier et la Troisième République,” CCHA Rapport, 18 (1950–51): 15–24. Montréal fin-de-siècle; histoire de la métropole du Canada au dix-neuvième siècle (Montréal, 1899). Eugène Normand [Alexis Pelletier], Le libéralisme dans la province de Québec (s.l., [1897]). Palmarè[s] du collège de L’Assomption, le 12 juillet 1865 (Montréal, 1865). Antonio Perrault, “Joseph-Israël Tarte,” Rev. canadienne (Montréal), 1 (janvier–juin, 1908): 104–24. Political appointments and judicial bench (N.-O. Coté). Protestation contre Tarte et sa clique . . . (s.l., s.d.). Léon Provancher, “Notre presse,” Le Naturaliste canadien (Cap-Rouge, Québec), 9 (1877): 137–39. Christian Roy, Histoire de L’Assomption (L’Assomption, 1967). RPQ. Rumilly, Hist. de Montréal, vol.3. H.-C.-B. Saint-Pierre, Affaire de W.-A. Grenier . . . 2 octobre 1897 (Montréal, [1897]). [J. S. C.] Würtele, Addresse de l’hon. juge Würtele aux petits jurés, le 2 octobre 1897, et allocution au défendeur . . . (Montréal, [1897]).

Bibliography for the revised version:

Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, “Ontario, Roman Catholic Church Records, 1760–1923”: familysearch.org (consulted 16 Oct. 2019). Parl. of Can., “Elections and candidates”: bdp.parl.ca/sites/ParlInfo/default/en_CA/ElectionsRidings/Elections (consulted 16 Oct. 2019).

Cite This Article

Michèle Brassard and Jean Hamelin, “TARTE, JOSEPH-ISRAËL,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 1, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/tarte_joseph_israel_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/tarte_joseph_israel_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | Michèle Brassard and Jean Hamelin |

| Title of Article: | TARTE, JOSEPH-ISRAËL |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1994 |

| Year of revision: | 2023 |

| Access Date: | April 1, 2025 |