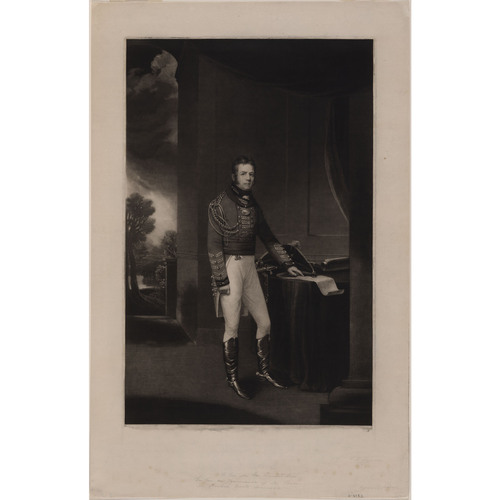

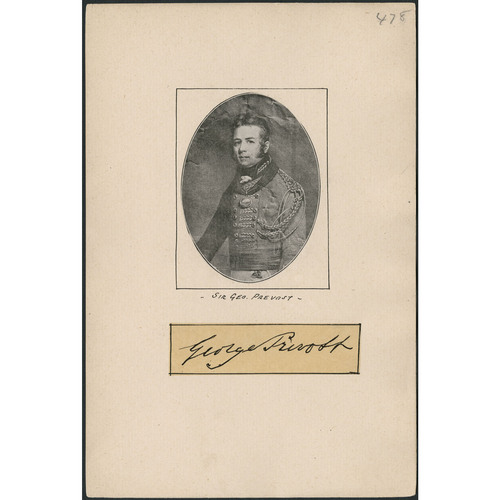

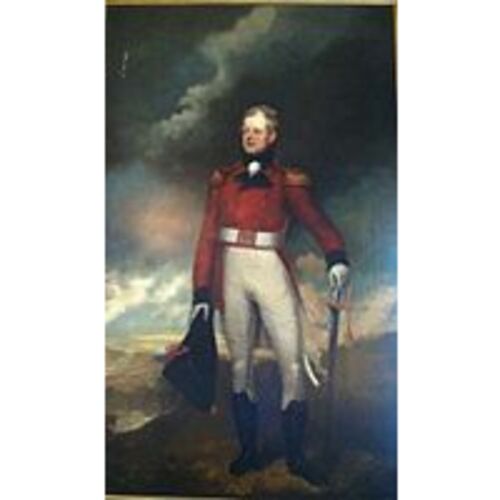

PREVOST, Sir GEORGE, army officer and colonial administrator; b. 19 May 1767 in New Jersey, the eldest son of Augustin Prévost and Nanette (Ann) Grand; m. 19 May 1789 Catherine Anne Phipps, and they had five children, one of whom died in infancy; d. 5 Jan. 1816 in London, England, and was buried in East Barnet (London).

George Prevost’s father was a French-speaking Swiss Protestant who had joined the British army; he was wounded at the siege of Quebec in 1759. At the time of George’s birth he was a lieutenant-colonel in the 60th Foot. George’s maternal grandfather was a wealthy Amsterdam banker, and his money no doubt later accelerated his grandson’s advancement in the British army. After education at schools in England and on the Continent, George was commissioned an ensign in his father’s regiment on 3 May 1779. He transferred to the 47th Foot as lieutenant in 1782 and to the 25th Foot as captain in 1784, and then rejoined the 60th on 18 Nov. 1790 with the rank of major. During the opening years of the war with revolutionary France, he saw service in the West Indies, commanding on St Vincent in 1794 and 1795; on 6 Aug. 1794 he was promoted lieutenant-colonel in the 60th Foot. Wounded twice on 20 Jan. 1796, he returned to England and received an appointment as an inspecting field officer. He was raised to the rank of colonel on 1 Jan. 1798, then brigadier-general on 8 March. In May he became lieutenant governor of St Lucia, where his fluency in French and conciliatory administration won him the respect of the French planters. In 1802 ill health compelled him to return to Britain, but on 27 September, after the resumption of war with France, he was chosen governor of Dominica. In 1803 he fought against the French to retain possession of that island and to recapture St Lucia. Promoted major-general on 1 Jan. 1805, he obtained leave to visit England, where he was placed in command of the Portsmouth district and created a baronet. The following year he became a colonel commandant in his regiment.

On 15 Jan. 1808 Prevost was appointed lieutenant governor of Nova Scotia and given the local rank of lieutenant-general. His appointment, like that of Governor Craig for Lower Canada the previous year, was made in accordance with a British decision to replace civil by military colonial administrators at a time of increasing tension in Anglo-American relations. Arriving at Halifax on 7 April, Prevost immediately set about his primary task of strengthening the military security of the Atlantic colonies. By the end of the month he had already taken steps to foment dissension in New England, where much opposition existed to the belligerent attitude of the American government towards Britain. Until hostilities began he sought to encourage New England’s violation of President Thomas Jefferson’s embargo on trade with Britain by having designated in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick a number of “free ports,” where American goods would be exempt from customs duties. The measure gave a substantial boost to Nova Scotia’s trade, not only with New England but also with the West Indies. Internally, Prevost could do little about the dilapidated state of fortifications in Nova Scotia, but he did secure from the legislature an amended militia law, which would permit mobilization of a small but efficient force to supplement the regular garrison in an emergency.

This law represented something of an achievement because relations between the executive and the House of Assembly in Nova Scotia had deteriorated under Prevost’s predecessor, Sir John Wentworth, who had tried to extend the executive’s prerogative at the expense of the assembly’s powers. When Prevost arrived, the assembly, led by William Cottnam Tonge*, was struggling particularly to assert control over government expenditures. Prevost shrewdly decided to conciliate Tonge, whom he appointed assistant commissary for an expedition that he was organizing as second in command against Martinique. He departed from Halifax on 6 Dec. 1808, taking Tonge with him. In the absence of the lieutenant governor the administration of the colony fell to Alexander Croke*, the senior councillor and a man as stubborn as he was reactionary. Instead of profiting from Tonge’s absence to maintain peaceful relations with the assembly, he fought with it over a supply bill, which he finally rejected on the ground that it encroached on royal prerogatives, and then quarrelled with the Legislative Council over the means of breaking the impasse.

Following his return to Halifax on 15 April, after the capture of Martinique, Prevost renounced Croke’s actions, restored “good understanding” with his council, and then placated the assembly (still deprived of Tonge, who had found a position in the West Indies) by refusing to quibble over constitutional niceties. On 10 June it not only passed a new supply bill, but also voted 200 guineas for the purchase of a sword for Prevost to mark its approbation of his conduct in the Martinique campaign. In the end, Prevost believed, he had successfully maintained the crown’s prerogative. Later in 1809 Prevost took advantage of his good relations with the assembly to secure a tax on distilled liquors in order to meet the cost of arms and accoutrements for the provincial militia. For the rest of his term as lieutenant governor he would ensure that no arbitrary act of the executive united an assembly often torn by each member’s scramble to obtain the maximum allocation for road construction in his constituency.

Beginning in 1810 Prevost undertook to buttress the tenuous establishment of the Church of England, thereby risking his hard-won popularity since that church’s claims on government alienated other denominations in the colony. He persuaded the British government to permit the use of surplus revenue in the arms fund for completion or repair of Anglican churches and the enlargement of King’s College at Windsor. Moreover, he appointed Anglican clergy as civil magistrates, took steps to protect school and glebe lands from encroachment or alienation, and placed Bishop Charles Inglis on the council. He also obtained an increase in Inglis’s salary, provided the bishop, who preferred to rusticate at Aylesford, resided in Halifax. In 1811 Prevost sought to improve clerical salaries by offering to suspend the unpopular collection of quitrents on land grants if the assembly made annual financial provision for Anglican ministers; the proposal was ultimately rejected. Perhaps to reduce criticism from the Presbyterian and Roman Catholic churches, in 1810 Prevost had also appointed a number of their clergy to be magistrates, and the following year he acknowledged the respectability of the Church of Scotland, if not a semi-official status for it, by authorizing a grant from the arms fund to one of its churches.

By May 1811 Prevost was prepared to risk his good relations with the assembly over its annual appropriation to compensate members for their expenses, feeling that it was irregular, liable to abuse, and “an evil highly dangerous to the prerogative of the Crown.” Before he came to blows with the assembly over payment of expenses, however, Prevost left Nova Scotia for Lower Canada with instructions to replace Governor Craig. Though Prevost was politically conservative, he had nevertheless remained pragmatic during his administration in Nova Scotia. He considered the contests of factions an unavoidable characteristic of colonial politics, which governors should accept philosophically and seek to temper by diplomacy and conciliation. Prevost also foresaw the drift towards greater local self-government. “My observation leads me to believe,” he wrote to the Colonial Office, “that as Nova Scotia becomes sensible of her adolescence, her dislike to control will become more evident, and her attempts to shake off the restraints of the Mother Country more frequent. – In short her ties in my estimation are those of necessity and convenience, more than of gratitude and affection.”

On 21 Oct. 1811 Prevost was commissioned governor-in-chief of British North America; having been promoted lieutenant-general on 4 July 1811, he was also made commander of British forces in North America. In this latter capacity he took over the presidency and administration of Lower Canada from Thomas Dunn on 14 September, the day after his arrival at Quebec, and he continued to govern as president until 15 July 1812. As commander-in-chief he was preoccupied with military preparedness. Because of the British army’s commitments in Europe, no significant reinforcement could be expected of existing forces in the Canadas, then numbering some 5,600 regular troops and fencibles, of which about 1,200 were stationed in Upper Canada in small, widely scattered garrisons. The Lower Canadian militia could boast 60,000 men on paper but was “ill armed and without discipline.” That of the upper province totalled 11,000, of which Prevost thought “it might not be prudent to arm more than 4000,” because many inhabitants, recent immigrants from the United States, were of doubtful loyalty.

Worried as well about the disposition of the Canadians if war broke out, Prevost sought to conciliate Canadian political leaders, who had been estranged by the partisan alliance that Craig had formed with the British oligarchy. Prevost soon concluded that the Canadian politicians were men “seeking an opportunity to distinguish themselves as the champions of the Public for the purpose of gaining popularity and . . . are endeavouring to make themselves of consequence in the eyes of government in the hope of obtaining employment from it.” He did not disappoint them. Over the course of his administration, through lavish, but judicious, use of patronage, he exploited rivalry in the Canadian party, where the leadership of Pierre-Stanislas Bédard* was contested by several aspirants. In 1812 the dangerously disaffected Bédard was given a judgeship at Trois-Rivières, away from the centre of political affairs; Prevost treated the moderate Louis-Joseph Papineau* as leader. Of the 11 persons nominated by Prevost to the Legislative Council between 1811 and 1815, five were Canadians, who had been virtually excluded from such appointments since 1798; two, Jean-Antoine Panet and Pierre-Dominique Debartzch*, had been prominent critics of Craig. Prevost’s strategy, he informed the Colonial Office, was to compose a council “possessed of the consideration of the country, from a majority of its members being independent of the government” in order to transfer to it “the political altercations which have been hitherto carried on by the governor in person.”

During a rapid tour of the Montreal region in September 1811, Prevost had “found the country in the hands of the priests,” and he determined “to seek the support and influence of the Catholic Clergy.” Specifically, he wanted the church’s support for a new militia bill, but more generally he saw the clergy as a counterweight to the nationalist and democratically inclined Canadian party. He was no doubt aided by a confidential report from Vicar General Edmund Burke (1753–1820) of Nova Scotia, who described him to Bishop Plessis* as “a quiet man, good, without prejudices,” adding that “never has a governor done more good in such a short time and so little bad.” With no control over the clergy and “only persuasion to employ,” Prevost offered Plessis an increase in the salary he received from government, civil recognition as bishop of Quebec, and support for a petition to obtain French priests who had emigrated to Britain during the French revolution. Initially sceptical of Prevost, Plessis was ultimately won over by his “obliging disposition.” In 1813 a less restrained Alexander McDonell*, Plessis’s vicar general in Upper Canada, would be completely conquered by Prevost’s personality. “In patience, equanimity and abstemiousness, he surpasses all the Bishops, priests & even friars I have ever been acquainted with,” he exulted to the bishop. “I might even add recluses and recolets.”

By early 1812 Prevost had already won over important elements of the Canadian élite, and in April he was able to secure from the House of Assembly a new militia act and funds for defence. Once fighting began, the latter were supplemented by the issue of army bills, an ingenious scheme devised by the merchant John Young. Prevost also obtained a generally faithful participation in the militia on the part of the habitants, in contrast to their virtual boycott of it during the American invasion of 1775–76 [see Benedict Arnold; Richard Montgomery*]. The enthusiasm of virtually all classes of Canadians resulted in part from a changed perception of the Americans: the élite feared the Protestantism, anglicization, republican democracy, and commercial capitalism that the Americans represented, whereas the habitants feared the loss to potential American immigrants of an ever diminishing acreage of unused land; all were ready to follow a governor able to acquire their confidence.

In Upper Canada the newly appointed administrator, Isaac Brock, had less success raising a militia because of the strong American element in the province. Prevost recognized, however, that, since troops could only be moved and supplied speedily by water, any numerical deficiency in land forces would initially be offset by the superiority of the British Provincial Marine over the Americans on the Great Lakes. His strategy, in line with instructions from London, was defensive, the key being to safeguard Quebec, the only permanent fortress in the Canadas. If the Americans launched a substantial, well-organized invasion, Prevost would have no choice but to fall back on Quebec and try to hold it until reinforcements arrived from overseas. Predatory, ill-concerted incursions by the enemy might be repulsed, provided limited resources were not squandered, but Prevost ruled out major offensive operations as imprudent. Initially, too, he wanted to avoid any provocative action, which might unite a divided American public behind the war. Once hostilities started in June 1812, Brock, although momentarily restraining a natural impulse to go to the offence, found this defensive stance irksome. That summer the initiatives taken by Captain Charles Roberts in capturing Fort Michilimackinac (Mackinac Island, Mich.) and by Brock in taking Detroit, gave an unexpected fillip to the morale of Upper Canadians and revealed American unpreparedness.

The conditional repeal by Britain of the controversial orders in council relating to the search of neutral ships led Prevost to arrange a local ceasefire early in August. This was rejected by President James Madison, and hostilities resumed in September. After an American invasion of the Niagara peninsula was repulsed at Queenston Heights, where Brock lost his life, and Major-General Henry Dearborn’s planned advance on Montreal petered out because his militia refused to cross into Lower Canada, the first season of campaigning closed with no American troops on Canadian soil. Despite pressure from John Strachan* and others that he now adopt Brock’s boldly offensive strategy, Prevost held firm to a defensive posture, and was supported in his decision by the Duke of Wellington.

By 1813 the naval contest on the Great Lakes was coming into prominence. Prevost’s emphasis on preserving control of the lakes induced the British government to place the Admiralty in charge of marine operations, and Sir James Lucas Yeo arrived at Quebec in May to take command. Although directly responsible to the Admiralty in London, Yeo was instructed to cooperate with Prevost in strategic planning and the conduct of operations. Before these measures could take effect, however, British supremacy on the lakes had already been successfully challenged; on Lake Ontario a squadron assembled by Commodore Isaac Chauncey at the important naval base of Sackets Harbor, N.Y., had been able to cross the lake and ravage York (Toronto) in late April 1813. To relieve the mounting pressure on the Niagara peninsula, where land forces under Brigadier-General John Vincent* had been seriously weakened through large-scale desertion from the militia, Prevost created a diversion in May by leading an amphibious expedition against Sackets Harbor while Chauncey’s fleet was still absent. Although a landing was effected, Prevost calculated that the forts could not be captured and accordingly withdrew. Thereafter naval operations on Lake Ontario failed to establish the supremacy of either side, and the opposing commanders avoided direct confrontation while they devoted their energies to shipbuilding; ultimately, completion in October 1814 of the 112-gun St Lawrence gave control of the lake to Yeo. On Lake Erie in September 1813 the destruction of the small British squadron under Robert Heriot Barclay* gave the Americans a considerable advantage in the struggle for the Niagara peninsula. Fortunately for Prevost, an attempt to sever the province’s lifeline in the east by an assault on Montreal failed through the incompetence of the American generals, who were defeated in engagements at Châteauguay, Lower Canada, and Crysler’s Farm, Upper Canada, by British forces of far inferior numbers under lieutenant-colonels Charles-Michel d’Irumberry* de Salaberry and Joseph Wanton Morrison* respectively.

In the spring and summer of 1814 the military situation in Upper Canada became grave once again, but in late summer Prevost’s prospects brightened considerably with the abdication of Napoleon and the consequent arrival in Canada of an additional 15,000 troops, led by four of Wellington’s most able brigade commanders. The British government now expected Prevost to undertake offensive operations, before the campaigning season ended, with two objectives in view: first, to destroy American naval establishments at Sackets Harbor and on lakes Erie and Champlain; and second, to occupy American territory in Michigan so that the British peace commissioners at Ghent (Belgium) could exact a more favourable boundary. Deciding that Sackets Harbor could not be attacked successfully until naval superiority on Lake Ontario had been regained, Prevost planned a combined land and naval operation against Plattsburgh, N.Y., on Lake Champlain. Early in September 1814 he set out with a powerful army, reinforced by seasoned Peninsular veterans, to which the Americans could oppose only a much smaller force. On reaching Plattsburgh, however, he delayed the assault until the belated arrival of the British fleet, led by Captain George Downie in the hastily completed Confiance, whose 36 guns, it was hoped, would wrest control of Lake Champlain from the Americans. Impatiently and precipitately, Prevost had goaded the junior and inexperienced Downie into joining a supposedly combined operation, but then unaccountably failed to provide the promised military backing when the British ships engaged in combat in Plattsburgh Bay. Downie was killed and his force defeated; perhaps prematurely, Prevost abandoned the whole enterprise and retired with a disgruntled army to Lower Canada. Glossing over his share of responsibility for the abortive venture, Prevost justified withdrawal on the ground that, even if Plattsburgh had been captured, it would have been extremely hazardous for the British army to have remained on enemy territory after the loss of naval supremacy on Lake Champlain. Consequently he had withdrawn his army, “which was yet uncrippled for the security of these Provinces.” This seemingly craven decision mortified the Peninsular veterans, who had grown accustomed to glorious victories under Wellington. They felt that their newly minted reputation had been tarnished by the pusillanimity of a commander who had gained his laurels in minor Caribbean skirmishes, and who combined incompetence on the field of battle with a niggling insistence on such petty matters as regulation dress, which had never troubled the Iron Duke.

On their return to Quebec and Montreal, officers consorted with leading members of the English-speaking community, many of whom had become Prevost’s political enemies. William Smith* commented that the officers were “heartily tired of this Country, as every military man must be, who has any reputation to lose, under such a Goose as our little nincompoop.” Smith and others of the English party felt that Prevost’s appeasement of the Canadians had been disastrous for their own survival in, and Britain’s control of, Lower Canada. The Anglican bishop of Quebec, Jacob Mountain*, whom Prevost described as having “far more disposition for Politics than Theology,” considered that he and his church had been abandoned, and that the Roman Catholic Church had been virtually established. One of the most caustic critics of the governor’s political strategy was Herman Witsius Ryland*, clerk of the Executive Council and formerly Craig’s civil secretary and intimate adviser, who wrote of Prevost: “There he sits, like an Idiot in a Skiff, admiring the Rapidity of the Current which is about to plunge him into the Abyss!!!” In the spring of 1814 Ryland, Mountain, Pierre-Amable De Bonne, and John Young, enraged by Prevost’s unwillingness to block the assembly’s impeachment proceedings against chief justices Jonathan Sewell* and James Monk* for alleged misdemeanours during Craig’s repressive regime, had organized a cabal in the Executive Council to agitate for the governor’s recall. During Prevost’s absence from Quebec on military business, the conspirators illegally dispatched an address to the Prince Regent, denouncing the pretensions of the assembly and the governor’s servility to it and to the Catholic Church.

Extending their campaign to England, Prevost’s critics furnished their London correspondents, such as Sewell, there to fight his impeachment, with malicious gossip based on the complaints of Prevost’s officers after Plattsburgh. Prevost and his assistant civil secretary, Andrew William Cochran*, tried to counteract the poisonous reports through Adam Gordon, a personal friend of Prevost in the Colonial Office, but complaints from the colony did not fall entirely on unreceptive ears. British ministers rejected the strident political protests of the Executive Council but were sorely disappointed at being deprived of decisive military victories. Wellington admitted that the war in North America had been successfully conducted until Plattsburgh, and he acknowledged that it was the lack of naval supremacy on the Great Lakes which had prevented Britain from capitalizing on its military superiority in 1814. He advised the ministers, however, that Prevost would have to be recalled for failing to accomplish what had been expected of him militarily, if only to placate public opinion at home.

On 1 March 1815 Prevost heard with relief that the peace treaty signed at Ghent between Britain and the United States had been ratified in Washington. The next day, to his utter amazement and mortification, he learned that he had been superseded as governor and summoned to London to defend his conduct of the Plattsburgh campaign against charges made by Yeo; since they had quarrelled violently after Prevost’s return to Quebec from Plattsburgh, there had been no love lost between the two men. Already Prevost’s health and spirits had been adversely affected by the persistent, spiteful sniping of his military and political critics; in November 1814 Cochran had remarked to his father that the governor had “a more careworn appearance and more thoughtful manner. He has lost much of that cheerfulness that he had when you first knew him, tho’ his good nature remains unchanged.” Relentlessly, the English party in the province kept up its attacks. Samuel Gale* and “Veritas” each printed a malevolent series of letters in the Montreal Herald and subsequently published them as pamphlets. A diligent investigation ensued to unmask “Veritas.” John Richardson*, a Montreal merchant and executive councillor, has been suspected, but the author was Solicitor General Stephen Sewell*, Jonathan’s brother, whom Prevost suspended for his involvement in the campaign against him. On an equally sour note, a vote by the assembly of £5,000 for plate as a testimonial to the departing governor was vetoed by the British majority in the Legislative Council. Early in April 1815 Prevost left Quebec, applauded in numerous addresses by Canadians, reviled by the British.

In England, Prevost at first retired to his estate of Belmont in Hampshire; he soon moved to London, however, as adverse effects on his health from the journey home became alarming. The government accepted his explanations of his military conduct, but in August 1815 a naval court martial of the surviving officers of the Plattsburgh Bay engagement decided, in line with Yeo’s evidence, that defeat had been caused principally by Prevost’s urging the squadron into premature action and then failing to afford the promised support from the land forces. Prevost requested a military court martial so that he might vindicate his conduct, and this was fixed for 12 Jan. 1816 to allow time for witnesses to travel from Lower Canada. Prevost, however, according to the Quebec Gazette, was suffering from “the combined effects of hereditary disease and the peculiar cruelty of his situation during the last few months,” and his health necessitated a postponement of the hearing until 5 February; he died of dropsy at the age of 48 exactly one month before the court martial was to convene. Although nothing could then be done legally to clear Prevost’s name, the Prince Regent responded to a petition from his widow for some mark of official favour by granting the family additional armorial bearings.

Unfortunately for Prevost’s posthumous reputation, this gesture could not repair the damage done by partisan vilification and contemporary strictures on his military conduct. The accusations broadcast by Gale and “Veritas” formed the basis of a censorious article in the Quarterly Review of London in 1822. On behalf of Prevost’s family and friends, his former civil secretary, Colonel Edward Brabazon Brenton*, replied anonymously, and far from convincingly, the following year in Some account of the public life of the late Lieutenant-General Sir George Prevost. . . . By that time the former governor was generally portrayed on both sides of the Atlantic as an affable but weak-willed individual, cautious to a fault, who had been found wanting in a crisis. This deprecatory estimate was made the standard judgement of writers and historians into the 20th century in part because of the myth, assiduously cultivated by John Strachan and the spiritual heirs of the loyalists; that Upper Canada had been saved from American conquest by the bravery of the local militia under Brock. Contrary to the traditional view, however, Prevost’s preparations for defending the Canadas with the limited means at his disposal had been energetic, well conceived, and comprehensive, and in the most taxing, hazardous circumstances he had achieved the primary objective of preventing an American conquest. Perhaps his character, abilities, and experience did not so well equip him to be a successful commander of field operations, but his military reputation would have stood higher had his exploits been compared not to those of Wellington, but to those of the opposing American generals.

At the same time, “this tiny, light, gossamer man,” as Chief Justice Sampson Salter Blowers* of Nova Scotia described Prevost, had been a most successful colonial administrator. Although like Craig and Wentworth instinctively conservative, Prevost distinguished himself from them by his realism and pragmatism. He was able to analyse the relative force of the social groups in a colony, understand the demands of the most influential, and formulate policies of appeasement that rendered British colonial rule palatable. Unperturbed by the dissensions that characterized relations between the houses of a colonial legislature and blessed with an obliging disposition and winning ways – “smooth & flattering; in manner like a Frenchman,” a later governor, Lord Dalhousie [Ramsay*], disparagingly remarked – Prevost’s varied employment in the West Indies and North America proved him uncommonly adept at dealing with sensitive colonial politicians, French- as well as English-speaking. In Lower Canada he was in part the undeserving victim of virulent political contests, endemic to a colony with representative institutions and ethnic antagonisms; in the early 1810s political polarization was too intense to be attenuated by personal conciliatory efforts. Nevertheless, the British government highly approved of Prevost’s strategy and instructed his successor, Sir John Coape Sherbrooke*, to continue the policy of conciliation that Prevost had resolutely, but vainly, pursued.

PAC, MG 23, GII, 10, vol.5; MG 24, A1; A9; A41; B3, 2–4; B16; J48; RG 8, I (C ser.), 366; 676–95B; 1215–27. PANS, MG 100, 152: no.1; RG 1, 58–59, 111, 287–88. PRO, CO 42/143–62; CO 43/22–23; CO 217/82–88; CO 218/19; WO 17/1516–20; WO 71/242; WO 81/52. SRO, GD45/3/542; GD45/3/552. “Campaigns in the Canadas,” Quarterly Rev. (London), 27 (1822): 405–49. Robert Christie, Memoirs of the administration of the colonial government of Lower-Canada, by Sir James Henry Craig, and Sir George Prevost; from the year 1807 until the year 1815 . . . (Quebec, 1818). Doc. hist. of campaign upon Niagara frontier (Cruikshank). Docs. relating to constitutional hist., 1791–1818 (Doughty and McArthur; 1914). The life and correspondence of Major-General Sir Isaac Brock . . . , ed. F. B. Tupper (London, 1845). N.S., House of Assembly, Journal and proc., 1808–11. Official letters of the military and naval officers of the United States, during the war with Great Britain in the years 1812, 13, 14, & 15 . . . , comp. John Brannan (Washington, 1823). [John Richardson?], The letters of Veritas, re-published from the Montreal Herald; containing a succinct narrative of the military administration of Sir George Prevost, during his command in the Canadas . . . (Montreal, 1815). Select British docs. of War of 1812 (Wood). [John Strachan], The John Strachan letter book, 1812–1834, ed. G. W. Spragge (Toronto, 1946). Montreal Herald, 1814–15. Quebec Gazette, 31 March, 14 April, 26 May, 2 June, 11 Aug., 1 Sept. 1808; 5 Jan., 15 June, 13 July, 28 Sept. 1809; 18 Jan., 15 Feb. 1810; 4 April, 29 Aug., 5, 19, 26 Sept., 3 Oct., 21 Nov. 1811; 7, 16 Jan., 21 Feb., 5 March, 9 April, 7 May, 2, 16 July, 10, 17, 24 Sept., 22 Oct., 26 Nov., 10, 29 Dec. 1812; 18, 25 Feb., 11, 18 March, 1 April, 13 May, 24 June, 7, 21 Oct., 29 Nov., 23 Dec. 1813; 12 Jan., 2 Feb., 16, 23, 30 March, 6, 13 April, 18 May, 10 Aug., 5 Oct. 1815; 29 Feb., 21 March, 21 Nov., 19 Dec. 1816; 8 Dec. 1823. Appleton’s cyclopædia of American biography, ed. J. G. Wilson and John Fiske (7v., New York, 1887–1900), 5: 116. DNB. G.B., WO, Army list, 1779–1816. H. J. Morgan, Sketches of celebrated Canadians and persons connected with Canada, from the earliest period in the history of the province down to the present time (Quebec and London, 1862; repr. Montreal, 1865). Wallace, Macmillan dict. Henry Adams, History of the United States (9v., New York, 1890–91). After Tippecanoe: some aspects of the War of 1812, ed. P. P. Mason (East Lansing, Mich., and Toronto, 1963). J. M. Beck, The government of Nova Scotia (Toronto, 1957). [E. B. Brenton], Some account of the public life of the late Lieutenant-General Sir George Prevost, Bart., particularly of his services in the Canadas . . . (London, 1823). A. L. Burt, The United States, Great Britain and British North America from the revolution to the establishment of peace after the War of 1812 (Toronto and New Haven, Conn., 1940). Christie, Hist. of L.C., vols. 2, 6. Craig, Upper Canada. Fingard, Anglican design in loyalist N.S. G. S. Graham, Sea power and British North America, 1783–1820: a study in colonial policy (Cambridge, Mass., 1941). Hitsman, Incredible War of 1812; Safeguarding Canada, 1763–1871 (Toronto, 1968). Reginald Horsman, The causes of the War of 1812 (New York, 1972). Lambert, “Joseph-Octave Plessis.” Lemieux, L’établissement de la première prov. eccl. C. P. Lucas, The Canadian War of 1812 (Oxford, 1906). W. S. MacNutt, The Atlantic provinces: the emergence of colonial society, 1712–1857 (Toronto, 1965). A. T. Mahan, Sea power in its relations to the War of 1812 (2v., London, 1905). Manning, Revolt of French Canada. Murdoch, Hist. of N.S., vol.3. Ouellet, Bas-Canada; Hist. économique. Bradford Perkins, Castlereagh and Adams: England and the United States, 1812–1823 (Berkeley and Los Angeles, Calif., 1964); Prologue to war: England and the United States, 1805–1812 (Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1961; repr. 1963). J. W. Pratt, Expansionists of 1812 (New York, 1925). “The late Lieut.-Gen. Sir George Prevost, Bart.,” Naval and Military Magazine (London), 3 (March 1828): 71–74. “Military services and character of the late Lieut.-Gen. Sir George Prevost, Bart.,” Naval and Military Magazine, 2 (September 1827): 101–10. J. M. Hitsman, “Sir George Prevost’s conduct of the Canadian War of 1812,” CHA Report, 1962: 34–43.

Cite This Article

Peter Burroughs, “PREVOST, Sir GEORGE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 5, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 19, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/prevost_george_5E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/prevost_george_5E.html |

| Author of Article: | Peter Burroughs |

| Title of Article: | PREVOST, Sir GEORGE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 5 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1983 |

| Year of revision: | 1983 |

| Access Date: | February 19, 2026 |