Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

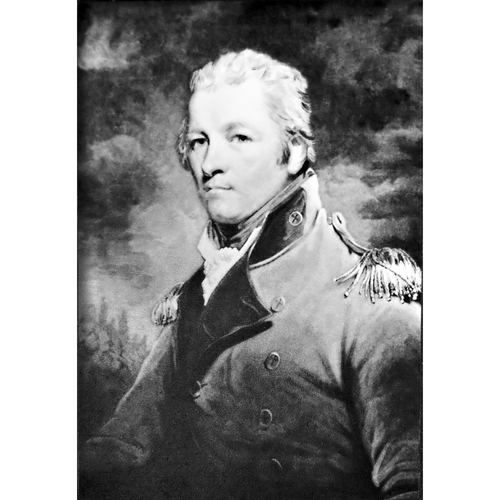

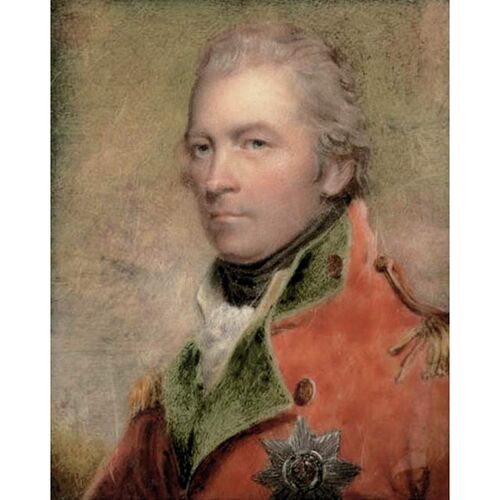

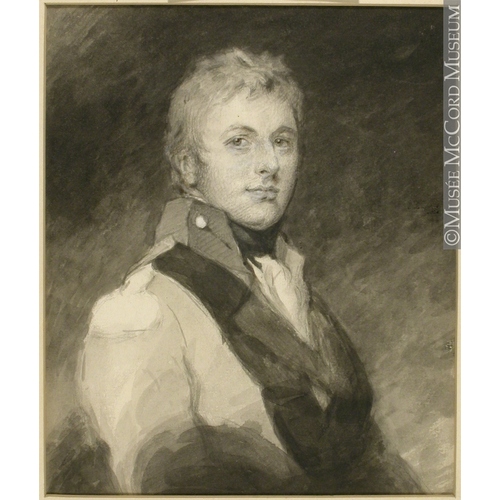

LENNOX, CHARLES, 4th Duke of RICHMOND and LENNOX, colonial administrator; b. 9 Sept. 1764 in England, eldest son of Lord George Henry Lennox and Lady Louisa Kerr, daughter of William Henry Kerr, 4th Marquess of Lothian; m. 9 Sept. 1789 Charlotte Gordon, daughter of Alexander Gordon, 4th Duke of Gordon, and they had seven sons and seven daughters; d. 28 Aug. 1819 near Richmond, Upper Canada.

Charles Lennox was apparently born in a barn, his mother having taken ill suddenly during a fishing trip. As a boy he joined the Sussex militia, in which he was promoted to a lieutenancy in 1778. Some six years later he became secretary to his uncle, Charles Lennox, 3rd Duke of Richmond and Lennox, as well as to the Board of Ordnance. On 29 Aug. 1787 he was commissioned a captain in the 35th Foot, and on 26 March 1789, thanks to the influence of Richmond with Prime Minister William Pitt, Lennox obtained a captaincy in the Coldstream Foot Guards, which carried with it a lieutenant-colonelcy in the army at large. The commander of the Coldstreams, Frederick Augustus, Duke of York and second son of King George III, was indignant to learn of the promotion, particularly since Richmond was a political enemy. When York made disparaging remarks about the courage of the Lennox family, Charles challenged him to a duel, and the encounter took place on 26 May. Lennox grazed the duke’s curl with a ball, after which York fired into the air, declaring that he bore his opponent no animosity. Lennox’s brother officers esteemed that he had “behaved with courage, but from peculiarity of circumstances, not with judgement”; their ambiguous verdict probably encouraged him to transfer back to the 35th Foot as lieutenant-colonel on 15 June. Fond of sports – his father was the founder of the Goodwood horse-races – Lennox was popular with officers and men alike. After serving with his regiment in the West Indies in 1794, he was appointed aide-de-camp to the king in January 1795. Promoted major-general three years later, on 17 March 1803 he became colonel of the 35th Foot. He was made lieutenant-general in 1805 and general on 1 June 1814.

In 1790 Lennox had been elected to his father’s seat of Sussex in the House of Commons, and he was re-elected in 1796, 1802, and 1806. He succeeded to the dukedom of Richmond and Lennox on the death of his uncle on 29 Dec. 1806. The following April he was appointed lord lieutenant of Ireland. His administration was comparatively quiet, despite his opposition to the removal of any political disabilities imposed by British law on Roman Catholics. In June 1812 he wrote to the Colonial secretary, Lord Bathurst, that he would remain in Ireland only so long as “nothing is done for the Catholics.” Despite his rigid political and religious views, Richmond’s interest in horse-racing, hunting, and other sporting activities, and his lavish hospitality, ensured him a certain popularity among the Irish. His appointment ended in 1813, and the following year he temporarily closed the family estate of Goodwood for reasons of economy and moved his family to Brussels (Belgium). There, on 15 June 1815, the Duchess of Richmond gave the famous ball at which Wellington learned of Napoleon’s advance into the Netherlands. Richmond was present at Waterloo, but simply as a civilian. The Richmonds continued to live in Brussels until 1818; on 8 May of that year the duke was appointed governor-in-chief of British North America. He does not appear to have sought the appointment, but he willingly accepted it.

Richmond arrived at Quebec on 29 July 1818, accompanied by his family and his son-in-law, Sir Peregrine Maitland*, who had been appointed lieutenant governor of Upper Canada. The duke had instructions from London to improve the defences of British North America, to expand inland navigation, and to encourage the settlement of disbanded soldiers and other British immigrants in the various colonies. After a preliminary survey, Richmond recommended the strengthening of the forts at Quebec, Île aux Noix, and Île Sainte-Hélène in Lower Canada and at Kingston in Upper Canada, the opening of navigation on the Ottawa and Rideau rivers, and the construction of canals at Lachine, Lower Canada, and between lakes Ontario and Erie; canalization of the Ottawa began during his régime. Among other suggestions were the improvement of the militia and the building of a military road between Lower Canada and New Brunswick.

Richmond had also received instructions to continue the policy of his predecessors, Sir George Prevost and Sir John Coape Sherbrooke*, by conciliating Canadian political and religious leaders. He gave assurances to Bathurst that he had overcome the initial suspicions of Bishop Plessis*, the result of his anti-Catholic record in Ireland, but Plessis nevertheless found Richmond less well disposed than Prevost or Sherbrooke had been. Accustomed to having direct access to the governor, the bishop found Richmond “in general . . . buttoned up tight about affairs and scarcely communicative.” “Everything is done by interim secretaries,” he added, “we have enemies among the most notable people.” Moreover, Richmond breathed new life into the Royal Institution for the Advancement of Learning, which was responsible for the colony’s public schools and was much contested by Plessis [see Joseph Langley Mills*]. Later Richmond asked Anglican bishop Jacob Mountain* to draft plans for a university to be founded under the auspices of the Royal Institution with the aid of a bequest from the merchant James McGill.

In politics, rather than conciliating the Canadian party, Richmond took counsel from the rival English party, and most notably from John Young in the crucial matter of provincial finances. The revenues of the executive alone being insufficient to meet the expenses of the civil administration, in 1818 Sherbrooke, with the approval of the Colonial Office, had arrived at a compromise with the House of Assembly, dominated by the Canadian party under Louis-Joseph Papineau*, whereby the assembly would meet the current expenses of government and wipe out a large accumulated deficit in return for an annual consideration of the estimates. However, Sherbrooke’s poor health and subsequent departure had prevented the passage of a regular supply bill sanctioning the arrangement in legislation. In March 1819 Richmond, who feared for the independence of the crown if Sherbrooke’s compromise was adopted, presented the assembly with the estimates of expenses for the year, prepared by Young, reintroducing items, such as sinecure salaries, that Sherbrooke had agreed to drop as part of the compromise. When the assembly once again eliminated these items, Richmond seized the opportunity to contest its claim to control the estimates and prorogued the legislature, lecturing the lower house on its responsibilities in a manner reminiscent of the unpopular Governor Craig. Richmond had been angered as well by the assembly’s refusal to follow the British practice of providing for a civil list, guaranteeing at least some of the salaries of office holders during the life of the king. To strengthen the hand of the administration, he sought to enforce the collection of lods et ventes, a crown revenue, and urged London to replace provincial acts regulating trade and imposing import duties by imperial ones, in order to ensure for the executive funds sufficient to make it independent of moneys voted by the assembly. Also concerned by the assembly’s disposition to ignore the Legislative Council, which was dominated by the English party, Richmond adopted as his own that party’s recommendation for the union of Upper and Lower Canada as a means of neutralizing the Canadian party in a combined elective assembly.

As in Ireland, Richmond considered the encouragement of leisure an important means of popularizing his administration, at least among the élite. According to Frederic Tolfrey, an officer of the garrison, Richmond, who had been “one of the finest tennis-players in England” and an excellent racket-baller, “joined the officers around him in all manly games with an unaffected urbanity and good nature that endeared the Duke to all.” He was patron of the Garrison Racing Club, and he encouraged the Tandem Club, formed to make winter excursions into the countryside, by taking his turn in a rotation among the principal families of the town to supply the excursionists’ luncheons. He also did much to promote the theatre; his sons and entire staff joined the garrison theatre group, and he himself attended all presentations, inviting the players afterwards to supper at the governor’s residence, the Château Saint-Louis. Tolfrey noted as well that “balls and parties were more numerous than ever; the hospitality at the Chateau was conducted on a scale of princely liberality, and the magnificent gold plate and racing cups of the Noble Duke astonished the Canadians not a little whenever any large State parties were given, and to which the natives on these occasions were invited.”

During the summer of 1819 Richmond undertook an extensive tour of Upper and Lower Canada. At William Henry (Sorel, Que.) he was bitten on the hand by a fox. The injury apparently healed, and he continued to York (Toronto) and Niagara (Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ont.), even examining military sites as far distant as Drummond Island. Returning to Kingston, he planned a leisurely visit to the settlements on the Rideau. During this part of the journey the first symptoms of hydrophobia appeared. The disease developed rapidly and on 28 August he died in extreme agony in a barn a few miles from a settlement that had been named in his honour. Some accounts suggest that the duke had been bitten by a dog; stronger contemporary evidence, however, supports the view that he had received the rabies infection from a fox. Richmond’s body was brought back to Quebec, where on 4 September it was buried in the Cathedral of the Holy Trinity.

Personally popular among the British élite in the Canadas, the Duke of Richmond was out of sympathy with the popular party in Lower Canada, whose claims outraged his ideas of the inviolability of the crown’s prerogative. His most enduring legacy in Lower Canadian politics was the conversion of his brother-in-law and close friend, the Colonial secretary, Lord Bathurst, to the English party’s view that compromise with the assembly over provincial finances was impossible. Relations between the British government and the assembly were thenceforth to deteriorate almost unrelentingly. Owing to Richmond’s early death, however, the political storm burst not over his own head, but over the heads of his successors.

ANQ-Q, CE1-61, 4 Sept. 1819. PAC, MG 24, A14. Bas-Canada, Conseil législatif, Journaux, 1819. Docs. relating to constitutional hist., 1791–1818 (Doughty and McArthur; 1914); 1819–28 (Doughty and Story; 1935). Gentleman’s Magazine, January–June 1819: 466–67. W. P. Lennox, My recollections from 1806 to 1873 (2v., London, 1874). The life and letters of Lady Sarah Lennox, 1745–1826 . . . , ed. [Mary Dawson], Countess of Ilchester and [G. S. H. Fox-Strangeways], Lord Stavordale (2v., London, 1901), 1: 300; 2: 69–70. “La mort du duc de Richmond,” BRH, 8 (1902): 30–31. “Particularités de la maladie et de la mort du duc de Richmond, par un officier de son état-major,” BRH, 10 (1904): 43–50. Spencer and Waterloo: the letters of Spencer Madan, 1814–1816, ed. Beatrice Madan (London, 1970). Montreal Herald, 4 Sept. 1819. Quebec Gazette, 21 May, 22 June, 27, 30 July, 20, 31 Aug., 14, 28 Sept., 5, 19 Oct., 2 Nov., 7 Dec. 1818; 28 Jan., 11 Feb., 8 March, 13, 27 May, 14, 17 June, 1, 5 July, 5, 30 Aug., 2, 6, 20, 23, 27 Sept. 1819; 20 Jan. 1820. Burke’s peerage (1890), 1159–60. Caron “Inv. de la con. de Mgr Plessis,” ANQ Rapport, 1928–29: 125, 129. DNB. “State papers, Lower Canada,” PAC Report, 1897: 253–56, 275–82. Lambert, “Joseph-Octave Plessis.” L. M. Lande, The 3rd Duke of Richmond, a study in early Canadian history (Montreal, 1956). Duncan McArthur, “History of public finance, 1763–1840,” Canada and its prov. (Shortt and Doughty), 4: 496–506, 509–11; “Papineau and French-Canadian nationalism,” 3: 289–93. [Daniel] MacKinnon, Origin and services of the Coldstream Guards (2v., London, 1833), 2: 30–32, 496–97. Manning, Revolt of French Canada, 43, 122–23, 133–34, 152, 200, 235. Millman, Jacob Mountain, 76, 175, 178, 181, 212, 274. Frederic Tolfrey, The sportsman in Canada (2v., London, 1845), 2: 198–221, 236–52. Douglas Brymner, “La mort du duc de Richmond,” BRH, 5 (1899): 112–14. E. A. Cruikshank, “Charles Lennox, the fourth Duke of Richmond,” OH, 24 (1927): 323–51. “Le duc de Richmond,” BRH, 10 (1904): 41–42. “Les funérailles du due de Richmond,” BRH, 42 (1936): 511–12.

Cite This Article

George F. G. Stanley, “LENNOX, CHARLES, 4th Duke of RICHMOND and LENNOX,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 5, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 17, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/lennox_charles_richmond_5E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/lennox_charles_richmond_5E.html |

| Author of Article: | George F. G. Stanley |

| Title of Article: | LENNOX, CHARLES, 4th Duke of RICHMOND and LENNOX |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 5 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1983 |

| Year of revision: | 1983 |

| Access Date: | December 17, 2025 |