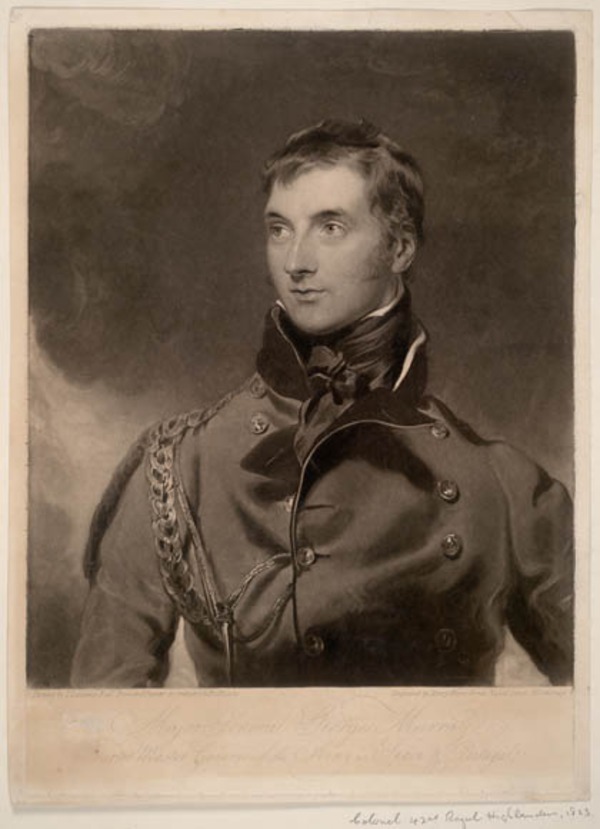

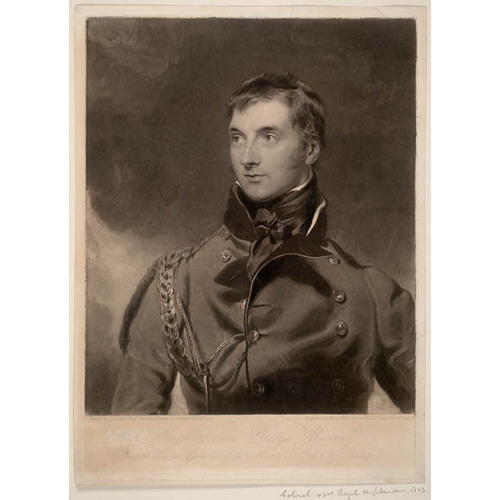

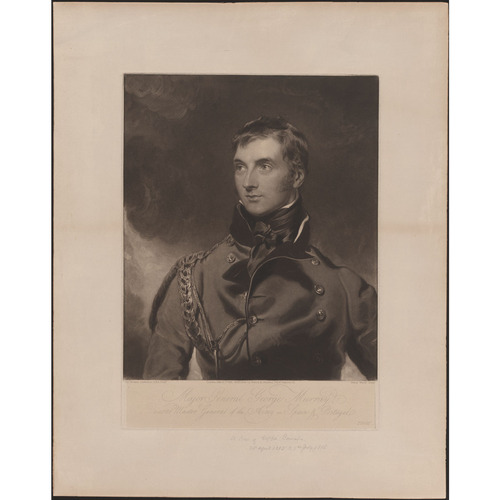

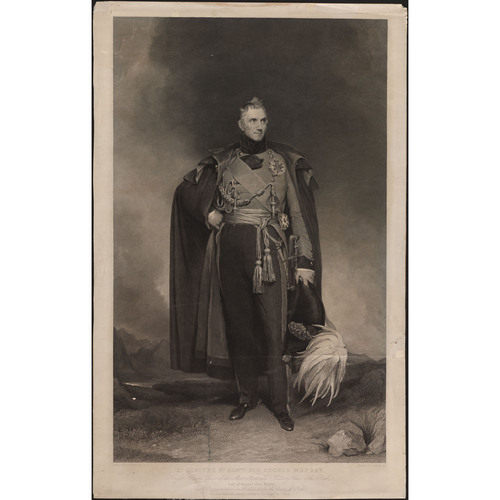

MURRAY, Sir GEORGE, army officer and colonial administrator; b. 6 Feb. 1772 in Ochtertyre, near Crieff, Scotland, son of Sir William Murray and Lady Augusta Mackenzie, daughter of the 3rd Earl of Cromarty; m. 28 April 1825 Lady Louisa Erskine; before their marriage they had one daughter; d. 28 July 1846 in London.

George Murray was educated at the High School of Edinburgh and the University of Edinburgh. On 12 March 1789 he received a commission in the 71st Foot, on 5 June he transferred to the 34th Foot, and on 7 July 1790 he purchased an ensigncy in the 3rd Foot Guards, becoming a captain on 16 Jan. 1794. During 1793 and 1794 he saw action in the Low Countries. On 5 Aug. 1799 he was made a lieutenant-colonel and joined the quartermaster general’s department. Between 1799 and 1806 he served in several minor campaigns, and in 1807 during the expedition to Copenhagen he worked closely with Major-General Sir Arthur Wellesley, the future Duke of Wellington. In 1808 Murray became quartermaster general of the army in Portugal and on 9 March 1809 was promoted colonel. During the Peninsular War his tactical arrangements made a substantial contribution to Wellington’s victories; on 4 June 1811 he was made a brigadier-general and on 2 December he was given the local rank of major-general. For the critical role he played in organizing Wellington’s advance through Portugal and Spain in 1812–13 he was awarded a Portuguese knighthood and on 27 Sept. 1813 was invested with the Order of the Bath.

In December 1814 Murray accepted a posting to British North America and, after a hazardous journey by sled from Halifax, arrived in Quebec on 2 March 1815. After notifying Governor Sir George Prevost* of his dismissal and while awaiting the arrival of Prevost’s successor, Sir Gordon Drummond*, Murray busied himself by preparing a study of the defences of the Canadian colonies. On 4 April Drummond appointed him commander of the forces and provisional lieutenant governor of Upper Canada. Murray assumed office on 25 April but was still awaiting instructions when he learned of the renewal of hostilities in Europe. At the end of May he left to rejoin Wellington but much to his chagrin missed the battle of Waterloo; he was made chief of staff of the army of occupation, and lived in splendour in Paris and Cambrai. He became, next to Wellington, the most decorated man in the British army. At this time he formed an attachment to Lady Louisa Erskine, the wife of Lieutenant-General Sir James Erskine of Torriehouse, with whom he lived continuously from 1820 and whom he married in 1825 after her husband’s death. The relationship was to cost him dearly socially and to hinder his political advancement. In November 1818 the allied army disbanded and Murray was appointed governor of the Royal Military College on 18 Aug. 1819. In March 1824 he was elected to parliament and on 6 March was selected by Wellington to be lieutenant-general of the Board of Ordnance. From 1825 he commanded the forces in Ireland until on 25 May 1828 he became colonial secretary in the Wellington government.

Although Murray had limited political experience, he was considered a “good man of business” and his appointment was popular among the British North American governors, many of whom had served with him in the Napoleonic Wars. Sir James Kempt* predicted Murray would make “a Capital Colonial Secretary” and expected to see him “cutting a figure in Parliament.” The appointment was also warmly received by colonial tories – such as John Strachan*–who had met Murray during his fleeting visit to Canada and who inundated him with advice. Both groups were doomed to disappointment. Murray was a conservative but one of a comparatively liberal bent who proclaimed himself “no enemy to that kind of reform which can be interpreted into a gradual, and cautious adoption of our Political system to the alterations of circumstances which time brings with it.” He was determined to discover “the views taken by opposite parties” in the colonies and to give the assemblies a “fair share of power.” Unfortunately Murray’s good intentions were not matched by his performance. He was not a good speaker and did not cut a figure in the House of Commons. Moreover, Murray found his work as secretary onerous and he exercised only a perfunctory control over business; in the words of a subordinate these were “years of torpor” at the Colonial Office. Nor did he represent his department effectively in Cabinet, where he was “overawed” by Wellington.

In 1828 when the House of Commons select committee on Canada recommended substantial reforms in the administration of the Canadas, Murray vacillated. Although he wished to end the prolonged dispute with the Lower Canadian assembly over the civil list, his indecision allowed that body to seize the initiative and left the governor, Kempt, in an untenable position. Murray also wished to settle the longstanding debate over the distribution of the clergy reserves in Upper Canada but, even though he rejected the “Exclusive Principle,” he was determined to give “peculiar encouragement” to the established churches of England and Scotland and he could not decide how to reconcile these objectives. By 1830 Wellington was under great pressure to transfer him to a less important post. When he left office that November he had, in fact, resolved few of the issues in dispute between the Canadian reformers and the British government and his departure was little regretted throughout British North America, even by those officials, such as Sir John Colborne*, whom he had appointed.

Murray lost his parliamentary seat in 1832 but regained it in 1834. He served as master general of the Ordnance, with a seat in the Cabinet, in Sir Robert Peel’s ministry (1834–35). He lost his seat again in 1835 and was defeated in 1837, 1839, and 1841, although he again served as master general of the Ordnance, this time without a seat in the Cabinet, from 1841 until 1846. On 27 May 1825 he had become a lieutenant-general; he rose to the rank of general on 23 Nov. 1841. Murray’s military reputation is secure, although overshadowed by Wellington’s, but he was one of the weakest secretaries of state in the first half of the 19th century and, though alone among them he had visited the British North American colonies, his impact there was slight.

[The papers of General Sir George Murray are found in NLS, Dept. of mss, Adv. mss 46.1.1–46.10.2. There is only one dispatch from Murray while he was in Upper Canada (PRO, CO 42/356: 61–63); however, the files for all the British North American colonies between 1828 and 1830 contain many items directed to him as well as a much smaller number of his responses. There are a number of letters between Murray and the Duke of Wellington in Despatches, correspondence, and memoranda of Field Marshal Arthur, Duke of Wellington, K.G., ed. [A. R. Wellesley, 2nd] Duke of Wellington (8v., London, 1867–80), and frequent references to Murray in the Dalhousie papers at the SRO, esp. GD45/3/27B: 159, 201, 215. [Edward Law, 1st Earl of] Ellenborough, A political diary, 1828–30, ed. [R. C. E. Abbot, 3rd Baron] Colchester (2v., London, 1881), [Harriet Fane] Arbuthnot, The journal of Mrs. Arbuthnot, 1820–1832, ed. Francis Bamford and [Gerald Wellesley, 7th] Duke of Wellington (2v., London, 1950), and Sir Henry Taylor, Autobiography of Henry Taylor, 1800–1875 (2v., London, 1885) are also useful. Murray’s military career is examined definitively in S. P. G. Ward, “General Sir George Murray,” Soc. for Army Hist. Research, Journal (London), 58 (1980): 191–208. Murray’s report on Upper Canada has been reproduced in G. S. Graham, “Views of General Murray on the defence of Upper Canada, 1815,” CHR, 34 (1955): 158–65. His career at the Colonial Office is assessed in D. M. Young, The Colonial Office in the early nineteenth century ([London], 1961) and my own Transition to responsible government. p.b.]

Cite This Article

Phillip Buckner, “MURRAY, Sir GEORGE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 7, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 30, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/murray_george_7E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/murray_george_7E.html |

| Author of Article: | Phillip Buckner |

| Title of Article: | MURRAY, Sir GEORGE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 7 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1988 |

| Year of revision: | 1988 |

| Access Date: | December 30, 2025 |