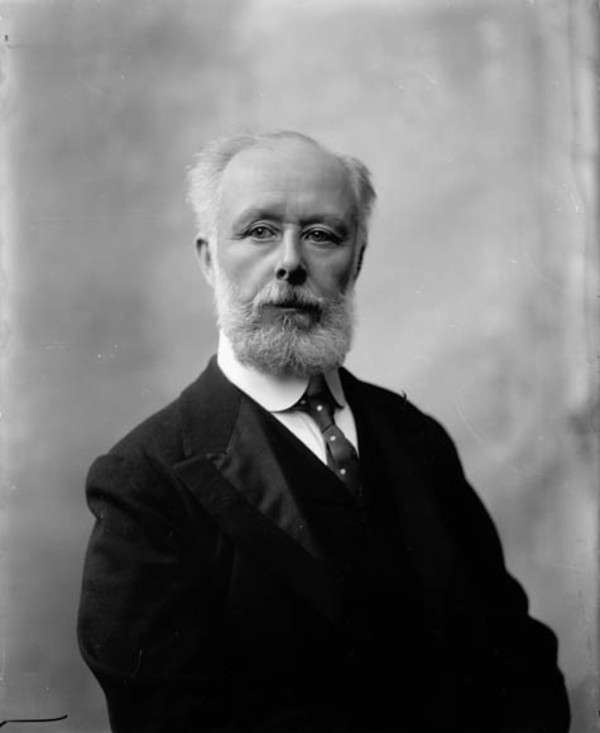

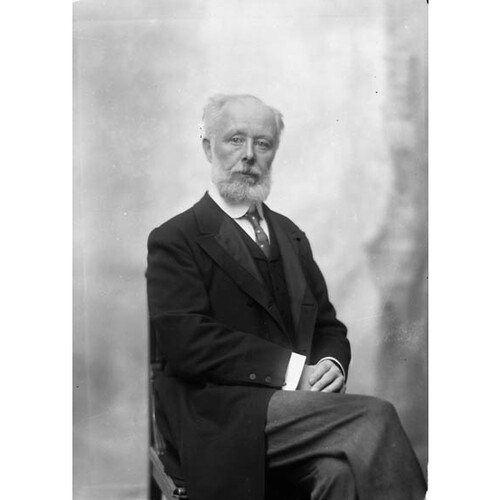

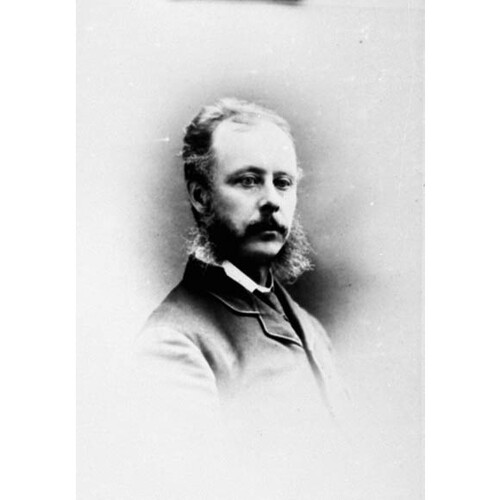

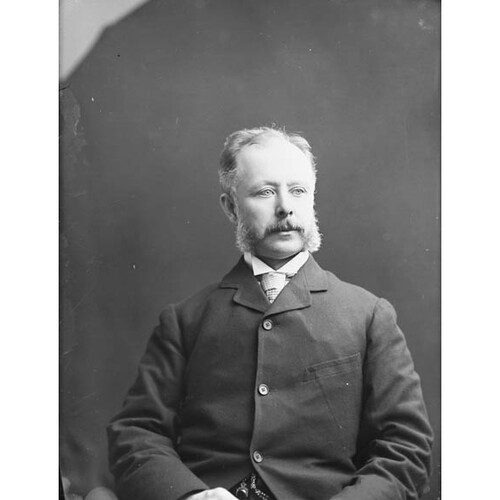

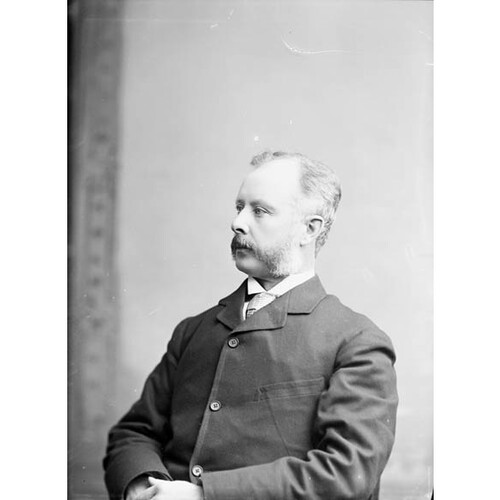

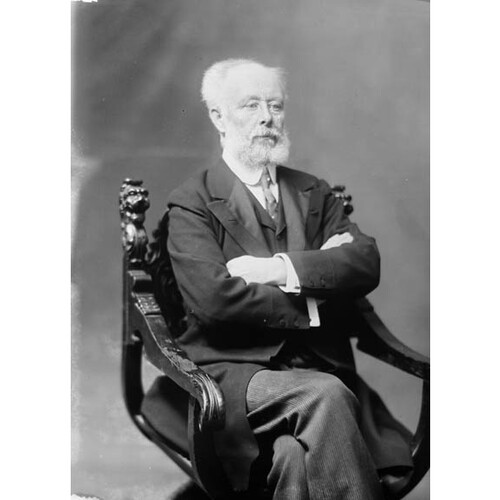

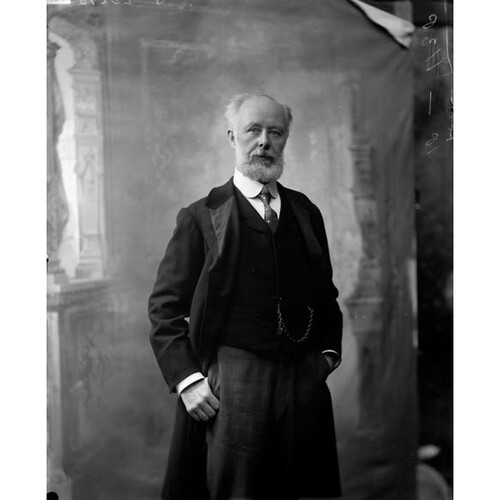

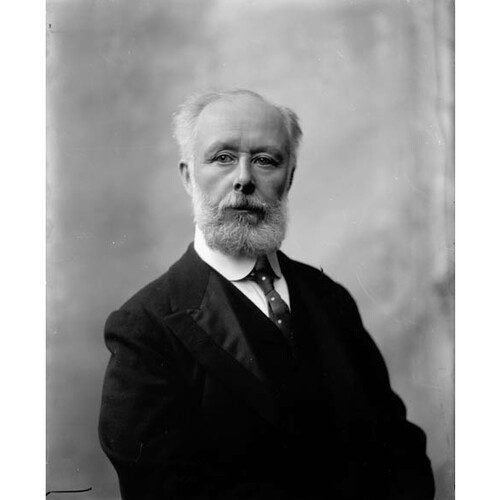

DAVIES, Sir LOUIS HENRY, lawyer, politician, and judge; b. 4 May 1845 in Charlottetown, son of Benjamin Davies and Kezia Attwood Watts; m. 23 July 1872 Susan Wiggins in St Eleanors, P.E.I., and they had two sons and three daughters; d. 1 May 1924 in Ottawa.

Of Huguenot background, Louis Davies’s paternal grandfather was born in Wales and came to the Island about 1812. Louis was educated at Charlottetown’s Central Academy and Prince of Wales College, and he subsequently read law at the Inner Temple in London. He was called to the bar in England in 1866 and, after a stint in the London law office of Thomas Chitty, on the Island a year later. Handsome and articulate, he quickly established a reputation as an orator and a first-rate cricket player. It was rumoured that his father, as the Island’s colonial secretary in 1869, invited his son to become solicitor general. In any event, young Davies did serve in that capacity in 1870 and 1872.

Throughout his early career he followed the lead of his father in opposing confederation with Canada. On 4 Feb. 1870 Louis introduced a motion at the Charlottetown Debating Club that the terms of union lately proposed [see Robert Poore Haythorne*] “are not just and equitable to PEI, and should not be accepted.” Benjamin saw the transinsular railway advocated by the government of James Colledge Pope* in 1871 as nothing but a ploy designed to put the Island in debt from which it could escape only with Canadian assistance. Louis joined him at many public meetings in opposition to Pope’s policy. In 1872 he successfully ran for the House of Assembly in 4th Kings, a constituency that was liberal and opposed the railway and the prevailing system of proprietorial land tenure. As soon as he was seated in the house, he challenged Pope, but he managed to avoid the sort of physical confrontations that led to the convictions of party leader David Laird* in police court. By 1873, despite their anti-confederation stances, the Davieses were willing to consider further negotiations with Canada, given the debt that the railway had in fact imposed on the colony. “Wise men changed their opinions when necessary,” Louis later argued in the assembly, “fools never did so.”

The entrance of the Island into the Canadian union on 1 July 1873 brought rapid political change. Several Liberals, headed by Laird, were elected to the federal House of Commons. The provincial party, its ranks thinned, chose Davies as its leader early in 1874. With confederation resolved, the assembly considered several issues that had been set aside in the interim. Like his father, Davies firmly supported legislative action to eliminate the Island’s landed proprietors. He opposed the Land Purchase Bill of 1874 because it was too generous to the proprietors, and was not unhappy when it was reserved [see Lemuel Cambridge Owen*]. A revised bill was proposed later in 1874, the same year that Davies began construction of Riverside, a large house in Charlottetown that he would occupy for part of every year until he died. The Land Purchase Act of 1875 was seen by contemporaries as a triumph for Davies, particularly in its provision for a land commission to set the purchase price of proprietorial land. As a lawyer, Davies initially declined to act for the tenantry before the new commission, but he relented and appeared along with Samuel Robert Thomson*; Edward Jarvis Hodgson appeared for the owners. Davies totally dominated the proceedings. His strategy was to build a case by looking for weaknesses in titles and diminishing the quality of the lands and the proprietorial improvements. Most observers thought he got a better deal for the tenants than anyone expected, with awards to the proprietors running at a fraction of what had been demanded.

The proprietors, however, did not accept without a fight. In November 1875 Hodgson appealed to the Island’s Supreme Court on behalf of Charlotte Antonia Sulivan, whose agent was George Wastie DeBlois*. Hodgson argued that the awards did not describe the lands in sufficient detail, that proper legal procedures had not been followed, and that the British North America Act did not permit such legislation as the Land Purchase Act. In January the court decided for Sulivan. Davies persuaded his government colleagues to appeal to the newly created Supreme Court of Canada in the name of the Island’s commissioner of public lands, Francis Kelly*. Kelly v. Sulivan thus became the court’s first case. Hodgson insisted that it could not hear the appeal because the appellant had not exhausted all the courts on the Island, specifically the little known Court of Error and Appeal, composed of the lieutenant governor in council. This local court was mentioned in statutes (and is now known to have functioned), but no record of its ever having met could be found in 1876, a point emphasized by Davies and his associates. In January 1877 the chief justice of the dominion court, William Buell Richards*, rejected the argument on jurisdiction since the Island court, if indeed it existed, had been abandoned. The remainder of the appeal went in favour of the province: the legislature had the right to pass the Land Purchase Act and the Island’s Supreme Court had authority only to see that matters were properly before the land commissioners and that no fraud was committed.

As the land case was unfolding, political attention also turned to the school question, which too had been put on hold during the uncertainties of confederation, but had earlier agitated the electorate. In the assembly in 1876 Davies had proposed and chaired a legislative committee, which reported that the Island’s Protestant and Catholic schools were in much need of reform and that there had been a substantial increase in sectarian teaching in recent years. A member of St Paul’s Anglican Church in Charlottetown, Davies made it clear that he favoured a single, non-sectarian system. Disagreements on educational policy were sufficiently strong to force the realignment of the traditional parties for the election of August 1876. J. C. Pope led the “Sectarian School” party against the “Free School” party headed by Davies, who decided to run in Charlottetown along with former adversary George DeBlois against Pope and Frederick de St Croix Brecken*. Davies spoke at meetings across the province and the Free Schoolers swept to victory. In Charlottetown he and DeBlois were easy winners. His party paid a price, when William Wilfred Sullivan* led the defection of four Liberals, but as a coalition of Protestant mhas, the Free Schoolers still had a majority. When John Yeo refused to become premier, Davies accepted the post, and that of attorney general, and appointed DeBlois as provincial secretary and treasurer. The alliance was an uneasy one, since Deblois became concerned over Davies’s involvement on behalf of the federal Liberals in a by-election late in 1876. To add to the strain, before Davies faced the assembly he fought off a bout of scarlet fever, which killed one of his sons. The new government met the house early in 1877, and moved quickly on schools. Adapted from New Brunswick legislation [see George Edwin King*], Davies’s Public Schools Bill, which passed in April, provided for a provincial board of education and non-sectarian schools. Catholic bishop Peter McIntyre* protested bitterly against the legislation and lobbied in Ottawa for its disallowance, but he was forced to come to terms with the province.

Davies’s administration had other difficult questions to face. Before confederation, Island governments had run deficits; a system of indirect taxation based on import duties proved inadequate. The financial settlement reached with Canada in 1873 masked the shortcomings, but by 1876 it was clear that taxation reform was necessary. It was equally clear that such change would be contentious, as was demonstrated in Charlottetown that year, when the city council petitioned the assembly for authorization to borrow money and tax personal property as well as rentals. Within days a petition signed by 600 citizens, including most of the city’s leading Tories, opposed the request; in the assembly Davies supported the proposed tax on property. In March 1877 he introduced a provincial taxation bill that authorized a revised land tax based on public assessment. The bill drew fire. Charlottetown and Summerside, which had municipal assessment, were exempted, and there was no mechanism for appeal. In meetings across the province, farmers complained about these inequities and the invasion of privacy.

With the countryside well agitated, Davies left to attend the Halifax Fisheries Commission [see S. R. Thomson], which was to settle Canadian-American differences left over from the Treaty of Washington (1871). It met every weekday from August to November. Faced with a well-appointed sideboard, short hours, and good pay, Davies preferred to remain until the end of the hearings, which decided in favour of a large award to Canada. While he was absent, criticism of his Assessment Act grew to fever pitch. The proprietors also roused themselves for a final contest with the land commission. Two of them, both Catholic McDonalds, appealed their awards to the Island’s Supreme Court, which granted nullification in August. Davies refused to negotiate new awards, however, and the court decided against the proprietors in 1878.

In the assembly that year, W. W. Sullivan continued to hammer at the coalition. Davies tried to mollify the critics of assessment by amending the legislation to provide for a court of appeal, but it was probably too late. The government was also stung by criticism of the financing of a new lunatic asylum. The coalition officially came unglued over Davies’s intense campaigning for the federal Liberals. On 20 Aug. 1878 George DeBlois and three Conservative colleagues resigned from the Executive Council, leaving Davies and a rump of Protestant Liberals to face the assembly. Davies made some attempt to attract Catholic support, but was told by assemblyman Nicholas Conroy* that Catholic voters found the acts of 1877 so offensive “that they will not readily forgive the gentleman under whose guidance those obnoxious laws had been enacted.” Following a motion of no-confidence on 6 March 1879, Davies resigned. In the ensuing election he and the Liberals went down to defeat; he returned to private practice and in 1880 was named a qc.

Although he was not to know it, the defeat marked the conclusion of his most fecund period of public service. He had settled the land and school questions – the most contentious issues on 19th-century Prince Edward Island – but in local political terms he had nowhere to go. Not surprisingly, he moved on to Ottawa, though he would always remain visible on the Island and be active in its fraternal, financial, and charitable organizations. He served for many years as president of the Merchants’ Bank of Prince Edward Island and of the Charlottetown Club, and in 1898 he was appointed an honorary lieutenant-colonel of the 4th (Prince Edward Island) Garrison Artillery Regiment.

In 1882, when public hostility to him had receded, Davies was elected to the House of Commons for Queens, which he would represent until 1896, when he was returned for Queens West. Beginning with his maiden speech in the house, delivered almost before he had unpacked, he established a reputation for his willingness to take on any of the Conservative government’s front-benchers. He also advanced in the inner circles of his party. He faithfully supported Edward Blake*, and after Wilfrid Laurier* became leader in 1887, he emerged as Laurier’s Maritimes lieutenant and a trusted strategy adviser, particularly on the Manitoba school question, where he felt his Island experience gave him special competence. Elected president of the Maritime Provinces Liberal Association in 1893, he was responsible for organizing the region for the 1896 election, which brought the Liberals to power.

Laurier made him minister of marine and fisheries, an area of considerable importance to the Maritimes. During Davies’s five years in this portfolio, a commission established fishing seasons and size limits for lobsters, a marine biological station was set up [see Moses Harvey*], and Canadian sovereignty was confirmed by an expedition to Baffin Island [see William Wakeham*]. Davies was also involved in a number of diplomatic missions. He went to Washington in 1896 to discuss reciprocal trade. A year later he accompanied his chief to the imperial conference in London; knighted there on 22 June, in July he was involved in legal presentations over Belgian and German trade treaties and, before the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council, over the division of federal and provincial jurisdictions in Canada’s fisheries. In 1897 he also accompanied Laurier (both acting as observers) to a meeting in Washington concerning the Bering Sea seal fishery. He met with the Americans again in 1898 in a series of gatherings that agreed to resolve pressing Canadian-American questions through a joint high commission. He was named to this commission, which broke off discussions in 1899 because of differences over the Alaska boundary. Later that year, when he attended the boundary talks in London, he was authorized to discuss with the Admiralty the possibility of a Canadian naval reserve. Nothing came of this initiative, although on his return Davies began upgrading his ministry’s fisheries protection service. In his entry in Henry James Morgan*’s Canadian men and women of the time (1912) it is claimed that he was the “father” of the imperial preferential tariff [see William Stevens Fielding] and of the dominion’s naval contingent. Neither claim has survived in Canadian historical writing.

In September 1901 Laurier named Davies to the Supreme Court of Canada, doubtless to reward his service to Canada and the party. The Canada Law Journal (Toronto) complained; other observers thought Davies lacked legal experience and was too political. The charge of inexperience was somewhat unfair. Davies had been a solicitor general of Prince Edward Island and an eminently successful lawyer in the land question. He would have over 20 years on the bench to prove his critics wrong. Instead, he remained intimately involved in Liberal politics. He became known for his lack of judicial independence and as a formalistic conservative and minimalist whose decisions challenged neither the status quo nor the lower courts. Few if any of his judgements have been cited for their cogency. To some extent his unwavering support of the powers of legislatures (as in Quong-Wing v. the King in 1914 or In re George Edwin Gray in 1918 [see John Idington]) may have reflected his encounters with Island proprietors who had used the courts to thwart the assembly. Honours did come to him – a portrait by fellow Islander Robert Harris* in 1902, a knighthood in the Order of St John of Jerusalem in England in 1913, and appointment to the imperial Privy Council in 1919 – but they were as much for the office as the man. Among his many affiliations, he was a president of the St John Ambulance Association, the Canadian Society of Charities and Correction, the Ottawa Anti-tuberculosis Association, and the Ottawa Archaeological Society. Lady Davies was equally active, as a founder of the local branch of the Women’s Canadian Historical Society and a vice-president of both the Ottawa Humane Society and the National Council of Women of Canada.

In 1918, following the resignation of Sir Charles Fitzpatrick* as chief justice of Canada, Davies campaigned vigorously to become his successor. Part of his appeal was that he would supposedly resign in 1921, when his pension rights reached their maximum. Prime Minister Sir Robert Laird Borden* carried the appointment in cabinet with difficulty. Davies was ill, old, and undistinguished. Although virtually inactive by 1923, he remained in office until his death in 1924, chiefly because of pension problems.

At his passing, Island newspapers described Davies as the province’s most brilliant son. Since that time he has been largely forgotten, commemorated only by the naming of the Island’s Supreme Court buildings after him. He has been neglected partly because fashions in historical reputations change – male lawyers, legislators, and judges are legion – and in part because he left no private papers and few published records, except in Island newspapers, Hansard, and the Reports of the Supreme Court of Canada. Moreover, no important off-Island achievements can be directly associated with him, and the on-Island ones date to a period with which few are familiar. Despite his elevation to the highest judicial office in the land, Davies’s Island career is probably more significant than his federal one.

AO, F 2; RG 22-354, no.11654. NA, MG 26, G: 188648. Charlottetown Guardian, 2 May 1924. Examiner (Charlottetown), 29 March 1879. Herald (Charlottetown), 25 Oct. 1871. Islander (Charlottetown), 23 July 1869. Patriot (Charlottetown), 22 Feb. 1873, 1 July 1875. D. [O.] Baldwin, “The Charlottetown political elite: control from elsewhere,” in Gaslights, epidemics and vagabond cows: Charlottetown in the Victorian era, ed. D. [O.] Baldwin and Thomas Spira (Charlottetown, 1988), 32–50. J. M. Bumsted, “Sic transit gloria . . . ,” Island Magazine (Charlottetown), no.47 (spring/summer 2000): 13–14. J. S. Cairns, “Louis Davies and Prince Edward Island politics, 1869–1879” (ma thesis, Dalhousie Univ., Halifax, 1982). Canada Law Journal (Toronto), 37 (1901): 677. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898 and 1912). CPG, 1874, 1877, 1898–99. J. T. Gay, American fur seal diplomacy: the Alaskan fur seal controversy (New York, 1987). Kelly v. Sulivan (1876), Canada Supreme Court Reports (Ottawa), 1: 3–64. Frank MacKinnon, “The Island knight: a sketch of the Rt. Hon. Sir Louis Davies,” Island Magazine, no.47: 3–12. W. E. MacKinnon, The life of the party: a history of the Liberal party in Prince Edward Island ([Charlottetown], 1973). A nation’s navy: in quest of Canadian naval identity, ed. M. L. Hadley et al. (Montreal and Kingston, Ont., 1996). P.E.I., House of Assembly, Debates and proc. (Charlottetown), 12 March 1874: 91–92. Report of proceedings before the commissioners appointed under the provisions of “The Land Purchase Act, 1875”, reporter P. S. MacGowan (Charlottetown, 1875). I. R. Robertson, “Religion, politics, and education in Prince Edward Island from 1856 to 1877” (ma thesis, McGill Univ., Montreal, 1968). I. L. Rogers, Charlottetown: the life in its buildings (Charlottetown, 1983). J. G. Snell and Frederick Vaughan, The Supreme Court of Canada: history of the institution ([Toronto], 1985). Standard dict. of Canadian biog. (Roberts and Tunnell). Vital statistics from N.B. newspapers (Johnson), 10, no.786; 14, nos.410, 443; 32, no.926. Who’s who and why, 1919/20.

Cite This Article

J. M. Bumsted, “DAVIES, Sir LOUIS HENRY,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 21, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/davies_louis_henry_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/davies_louis_henry_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | J. M. Bumsted |

| Title of Article: | DAVIES, Sir LOUIS HENRY |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | January 21, 2025 |