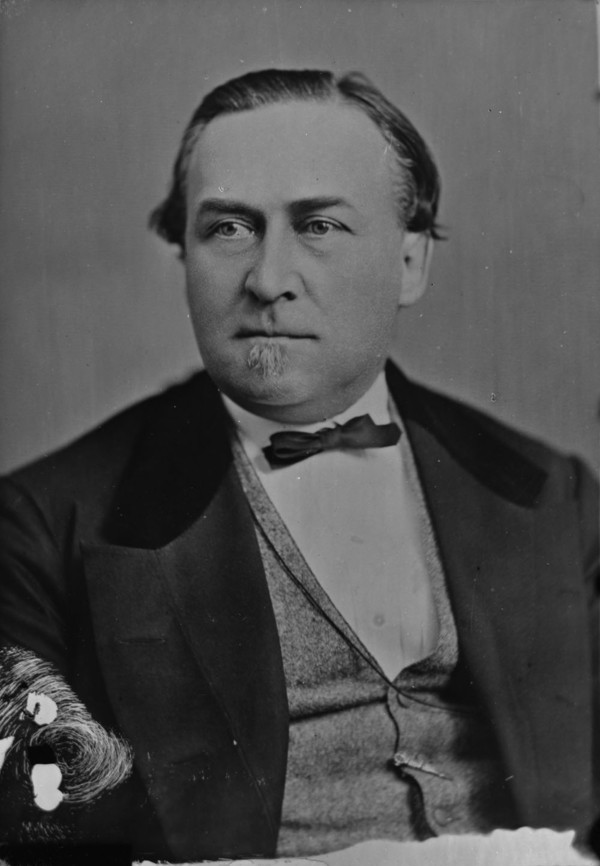

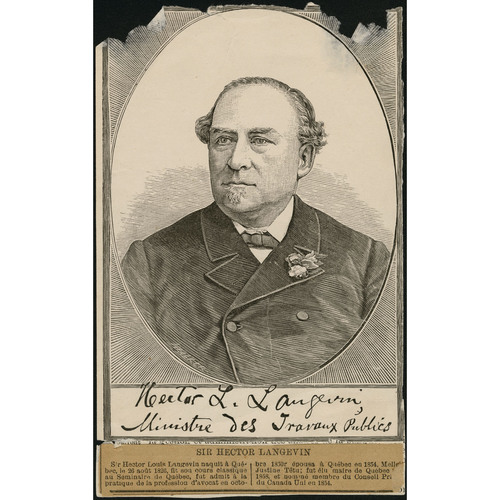

LANGEVIN, Sir HECTOR-LOUIS, lawyer, journalist, and politician; b. 25 Aug. 1826 at Quebec, son of Jean Langevin and Sophie Laforce; m. 10 Jan. 1854 Marie-Justine Têtu, daughter of Charles-Hilaire Têtu*, in Rivière-Ouelle, Lower Canada, and they had nine children, including Hectorine, who married Thomas Chapais* in 1884; d. 11 June 1906 at Quebec.

Hector-Louis Langevin was descended from a soldier in the Régiment de Carignan-Salières, which Jean Talon* settled in Bourg-Royal (Quebec) between 1666 and 1669 after a major expedition against the Iroquois. On 26 Nov. 1668 at Quebec, Jean Bergevin, dit Langevin, married Marie Piton, a native of the parish of Saint-Paul in the diocese of Paris. Their family worked the land until early in the 19th century, when Jean, the father of Hector-Louis, abandoned farming to become a shopkeeper and office holder at Quebec. Jean’s marriage on 15 Aug. 1820 to the daughter of Pierre Laforce, a notary, confirmed his rising social status. Their children would be members of what one historian has called “the cultured and civilized middle class of the capital.”

Jean and Sophie Langevin had 13 children, of whom five boys and two girls survived. The eldest, Jean* and Edmond*, who became respectively bishop of Rimouski and vicar general of the dioceses of Quebec and Rimouski, formed with Hector-Louis a tightly knit trio who would wield considerable power behind the scene in politics. Rightly or wrongly, Quebec historians have often seen the three brothers’ close alliance as symbolizing the union of church and state that dominated the history of French Canada during the second half of the 19th century. For Hector-Louis, the alliance with his brothers in the church would prove a double-edged sword, used as often by his opponents as by his friends.

Langevin was born at Place du Marché (Place Royale), near the church of Notre-Dame-des-Victoires in the Lower Town of Quebec. When he reached the right age, he went to the Malone sisters’ school on Rue des Casernes (Rue Christie), then had Clément Cazeau as a teacher, most likely at the school run by the Education Society of the District of Quebec on Rue des Glacis, and subsequently attended the Petit Séminaire de Québec. In 1847 his interests turned to law. Since he had followed his family to Montreal, he studied under Augustin-Norbert Morin* and later George-Étienne Cartier*. His correspondence with his brothers indicates that he was consumed with ambition. In July 1845 he had announced his choice of career to Edmond declaring: “The priesthood is a great calling, it is sublime, it exalts a man . . . but your status as country priests cannot help enhance the prestige of our name. For myself, I will bear the name of Langevin gladly; perhaps I will make it a bit better known than it is today. . . . As a descendant of the Laforce and Langevin families, I will be whatever God commands me to be, even . . . but I will say no more; that is my secret, that is my future. My brother, if you have any interest at all in your brother, you will keep this letter; and someday you may be able to add the missing word.”

On 17 July 1847 Langevin took the first step in a political career where he dreamed of reaching the top. He became the editor of the weekly newspaper Mélanges religieux, the official organ of the diocese of Montreal. There is no doubt that at the time he was the instrument of the reform leaders, who used his good relations with the clergy to “convert” Bishop Ignace Bourget* of Montreal. Bourget claimed to be politically neutral, but his sympathy for the Conservatives was well known. For two years Langevin filled the Mélanges religieux with articles about events of national or worldwide concern, if they would affect the future of Lower Canada. His main interest was politics. His writings reveal him as a cautious and slightly aloof nationalist, an enlightened liberal, and a reformer. Specifically, Langevin opposed the radicalism and anticlericalism preached by L’Avenir and the annexation to the United States called for by the Tories and Louis-Joseph Papineau*’s supporters. He advocated instead a federation of the British North American colonies, putting forth all the arguments that would be used by the Fathers of Confederation during the debates of 1864–67. In 1849 Langevin left the Mélanges religieux, which was abandoning polemics to resume its essentially religious character. He pursued his career as a journalist, however, in various other papers, including La Minerve.

On 9 Oct. 1850 Langevin was called to the bar. He initially decided to make his home in Montreal, but a year later he returned to Quebec, rejoining his family and friends who could help his career. In 1856 he was elected to the municipal council for Palais ward. Two years later he became mayor of Quebec, an office he held until 1861. Reorganization of the city’s finances and construction of the North Shore railway were his two main projects. In the first he was successful. In the second he ran into competition on the London market from the directors of the Grand Trunk, to the detriment of the Quebec economy and the development of the Saint-Maurice region. Langevin saw this set-back as one more reason to focus his energies on the broader political scene.

In the election of 1857–58 Langevin had been returned to the Legislative Assembly of the Province of Canada for Dorchester. Although he was connected with the Liberal-Conservatives led by Cartier, party lines were fluid and he voted in the house, as others did, according to conscience. It was ideology that led Langevin to move permanently into the Conservative camp. Indeed, liberalism was then so radical that it generated its own opponents, who joined forces with the clergy and society, itself conservative.

With the ardour of the rising generation, Langevin participated in the last acts of the government, as solicitor general from 30 March 1864 to 2 Nov. 1866, and then as postmaster general. He was a member of the “Great Coalition” of 1864. In that capacity he attended the three preparatory conferences on confederation and took an active part in framing the constitution of 1867. For him the objectives of confederation were clear and noble: to defend the general interests of a great country and powerful nation by means of a strong central power, which must protect the rights of the different ethnic groups. He paid close attention, therefore, to the particular interests of the distinct society that was Lower Canada and he took it upon himself to interpret to the political leaders the demands of the Catholic hierarchy. At the London conference in 1866, he exerted a decisive influence upon his colleagues to ensure that the constitutional text respected the spirit of the agreement that had been reached in Canada. He thus became one of the Fathers of Confederation and carved a place for himself in the political history of Canada, a place he would hold for 25 years in difficult and often hostile circumstances.

Langevin shared with Cartier the political leadership of the province of Quebec and the task of shaping the new Canada. It was a heavy load for the two men. Unable to fulfil every aspiration, they often had to contend with the frustrations of friends, the demands of the clergy, the rivalry between nationalisms, the claims of ethnic groups, and the tactics of an increasingly well-defined opposition. Confederation was fragile and the party supporting it had neither cohesion nor internal strength. These weaknesses, even more than ambitions of men, may explain why the leaders relied on dual representation to exert a wider influence. Langevin was one of the 18 members from Quebec province who held seats in both the provincial and federal houses. In Ottawa he was also secretary of state and superintendent general of Indian affairs. In 1869 Sir John A. Macdonald* gave him the influential portfolio of public works, an assignment quite in keeping with his abilities and ambitions.

The administration of this department made great demands on Langevin. Canada was only two years old, and there was much to be done. And so he signed up for the task. Many great projects of the post-confederation period, including the noted Langevin Block in Ottawa, bear witness to his concern for the image of the newborn country. Macdonald would term him “a first-rate administrator” and as long as he was in office he would keep Langevin in charge of public works.

Under the influence of a prime minister who, in the absence of a legislative union, wanted a strong central government, Langevin adopted a distinctly centralist position, as did his colleagues in Ottawa. This stance gave rise to provincial-rights movements, stirred up Quebec nationalism, and created mistrust towards the federal ministers. Soon the intrusion of federal ministers into local affairs was being denounced in the Quebec legislature, as were Ottawa’s grandiose policies, which drained Quebec financially instead of helping it to stem the tide of emigrants to the United States. The Red River uprising in 1869 did not help matters. There was an outcry in the press and from public platforms at the treatment given Louis Riel* and the French-speaking Métis by the Canadian government, which was building its empire in the west without regard for the indigenous population. A movement was formed for the defence of “the race,” which weakened still further the authority of the Quebec mps in Ottawa. But the government’s problems were just starting, since the demands of the provinces would become greater and greater with the economic and social development of the country.

As a federal minister, therefore, Langevin was partially responsible for the beginnings of the constitutional conflict and the difficult federal-provincial relations that have characterized Canadian history since confederation. Clearly, like many others he had shifted his allegiance to Ottawa, and his priority was the defence of the federal government’s major projects, especially after dual representation was abolished in Quebec in 1874.

It must be said that in this province, the omnipresent Catholic Church and its internal struggles, which had powerful repercussions on the political scene, had a paralysing effect on 19th-century politicians. Unlike many of his colleagues, including Cartier in Montreal, Langevin did not have to declare himself for or against the Programme catholique [see François-Xavier-Anselme Trudel*], published in April 1871, since Archbishop Elzéar-Alexandre Taschereau* of Quebec had repudiated it. But on the New Brunswick schools question [see George Edwin King] he had to take a stand against the ultramontanist newspapers Le Nouveau Monde and Le Journal des Trois-Rivières, the official organs of the dioceses of Montreal and Trois-Rivières.

When the Canadian government declared in 1872 that the New Brunswick law withdrawing all financial support from Catholic schools was constitutional, the ultramontanists demanded the heads of Langevin and other mps from the province of Quebec. Langevin’s position was clear. He explained it to his brother Jean on 16 June, showing his hostility to the inflexible ultramontanists, who denounced every trace of liberalism: “I do not believe that we federal ministers have to ask the episcopate for its opinion. . . . The bishops of our province know very well that when there has been any doubt we have not hesitated (at least I have not) to consult the bishops. But it would be ridiculous for me to do so today, because it is not a matter of knowing whether the New Brunswick law is good or bad, since we have all condemned it, but rather of knowing whether, constitutionally speaking, the New Brunswick legislature had the legal right to pass this law.” Bishop Jean Langevin, supported by Taschereau and Bishop Charles La Rocque* of Saint-Hyacinthe – all of them leaned towards moderate ultramontanism – came to the assistance of the federal ministers during the 1872 election campaign. The government was re-elected, but the future was beginning to look dark for the Conservative party.

Cartier was defeated in Montreal and died in England on 20 May 1873. Langevin inherited the leadership of the Quebec wing of the Conservatives because he was, in Macdonald’s eyes, “the best man.” It was a heavy legacy. In addition to being poisoned by internal divisions (although the Programmistes were beginning to disband), the party had too few genuine friends and too few youthful members who could revitalize it; it was also suffering from the repercussions of the worldwide depression, which was cutting off many opportunities for young people. It was indeed in a tenuous position in Ottawa. The 1872 election had reduced its parliamentary majority and the government was shaken by the Pacific Scandal, which involved, according to the opposition, the sale of the transcontinental railway charter to Americans in return for contributions to the Conservatives’ election fund.

Langevin was implicated in this affair. He was believed to have received some $32,000 for the campaign in the Quebec region. On 5 Nov. 1873 Macdonald and his colleagues had to resign. In the subsequent election Langevin could not find a riding where he could run with any chance of success. Humiliated at being pushed aside in this way, he returned to private life. However, he was not resigned to putting such an early and shameful end to his political career. Although the leadership of the Quebec wing of the party went to Louis-Rodrigue Masson, Langevin remained on the alert, waiting for a by-election in a rural riding, as Macdonald advised him to do. The opportunity came on 22 Jan. 1876 in Charlevoix. His opponent was Pierre-Alexis Tremblay*, whose election in 1872 had just been declared invalid by the Superior Court. With the support of Joseph-Israël Tarte, Langevin took the seat, but Tremblay contested the outcome on grounds of undue clerical influence.

The legal battle over Charlevoix represents a long and painful ordeal in Langevin’s career, since he found himself torn between his own cause and that of the clergy. It also constitutes an important page in the history of Quebec, because it called in question fundamental principles of both civil and religious orders. A new electoral law had come into force, and the clergy’s use of political influence was being challenged even in its own ranks. As well, the ruling Liberal party had long-time foes to destroy, and there were fears that a Protestant league might be formed in alliance with it. In this context one can see how Langevin might present a choice target, indeed be an easy prey for his enemies.

On 28 Feb. 1877 the Supreme Court of Canada declared the election in Charlevoix invalid because of undue influence. Nevertheless, in the subsequent by-election on 23 March Langevin was returned once more in the riding. He sat on the left side of the house for three sessions, but his authority was undermined by the events of the previous four years. In the general election of 17 Sept. 1878 he was defeated in Rimouski. He had thought he was on safe ground in his brothers’ diocese; the influence of the parish priests, however, worked in favour of the Liberal candidate, Jean-Baptiste-Romuald Fiset, perhaps as a reaction to Bishop Langevin’s authoritarianism. But Trois-Rivières elected him by acclamation, and so he took his place again in the Macdonald cabinet, as postmaster general from 19 Oct. 1878 to 19 May 1879, and then in public works. Macdonald said of him at the time, “Langevin does not enjoy the confidence of his countrymen, very unjustly I think, as he is the ablest of them.”

In 1879 Macdonald transferred railways and canals to a department independent of public works. Under the terms of the legislation, Langevin kept control of construction and of public buildings, ports, harbours, rivers, docks, dredging, slides and breakwaters, military and interprovincial roads, and telegraph lines. In May 1883 he presented a voluminous general report on the activities of the Department of Public Works from 1 July 1867 to 30 June 1882. To read it is to watch the creation of a nation, and become aware of the true accomplishments of Langevin, a man with the abilities of a good engineer, if not of a clever politician.

During the 1880s Langevin was again officially Macdonald’s Quebec lieutenant. But the task of rebuilding the unity of the party’s Quebec wing was beyond him, and his failure cost him his authority and prestige. Among the provincial Conservatives of that decade, the strong personalities were Masson and Joseph-Adolphe Chapleau*: Masson because of his uprightness and his remarkable independence of mind and spirit; Chapleau, paradoxically, because of his insatiable ambition and his political charisma. But they both stood out because they had deep-seated nationalist convictions that were attached first of all to the interests of the province of Quebec, a nationalism eroded in Langevin’s case by the exercise of power in Ottawa. Langevin had become an ardent federalist, inspired by a strong national sentiment. He embodied the centralizing spirit of the country’s founders and gave his support to the national economic agenda: the colonization and development of the west, the establishment of a transcontinental rail network, and industrialization through protectionism. He no longer spoke quite the same language as the leaders of Quebec, who preferred to hold their discussions with Masson, or even Chapleau.

There were times, however, when Langevin gained stature in the eyes of the Quebec Conservatives. In 1879 he carried out a delicate diplomatic mission to London, settling the Letellier affair. As a result Governor General Lord Lorne [Campbell*] was forced to follow the advice of his cabinet and remove from office Lieutenant Governor Luc Letellier* de Saint-Just, who had dismissed the Conservative administration of Charles-Eugène Boucher* de Boucherville on 2 March 1878. Letellier’s dismissal is generally regarded as a victory for democracy in Canada. On 24 May 1881 Queen Victoria made Langevin a kcmg.

In 1885 Langevin and his French-speaking colleagues in the cabinet were shaken by a second uprising in the west, which led to the hanging of Louis Riel on 16 November. There is no question that Langevin used all his influence, both with Macdonald and behind the scenes on Parliament Hill, to try to save the Métis leader from the scaffold. But in public he adopted a carefully considered and resolute position, unlike Chapleau and Sir Adolphe-Philippe Caron. He chose to remain silent while his two colleagues tried to explain Riel’s execution. Despite unrest in Quebec and the formation of a pro-Riel movement that gave rise to Honoré Mercier*’s Parti National and to demands for the resignation of the French Canadian ministers, Langevin retained his portfolio. He explained his position to his brother Edmond on 20 November: “If we had withdrawn from the cabinet on this question, what would happen? Riel would have been hanged anyway, and we would have raised an impenetrable barrier between the present government and French Canadians. We would shut ourselves out of the government, and by keeping to themselves French Canadians would unite the English element against them and involve us in a war of races, of nationalities.” But the Riel affair was a fatal blow to the Conservative party: “Do you not agree with me,” mp Alphonse Desjardins* wrote to Masson, “that it marks the beginning of the end of a reign? Sir John saw the dawn of his political career lit by the glow from the burning parliament buildings in Montreal; its sunset will fade behind the gallows in Regina.”

Admittedly there were other causes for the decline of the Conservative party, especially the centralization of the federal government and its tariff policy, both of which aroused discontent in one province or another. It is significant that the provinces attending the interprovincial conference which Mercier called in 1887 were unanimously opposed to Ottawa despite the diversity of their grievances and interests. After 20 years of existence, Canadian federalism was already up for reconsideration.

In the 1887 election – which saw the opposition calling the federal ministers “hangmen” – Langevin won by a narrow margin in Trois-Rivières through the influence of Bishop Louis-François Laflèche*, who supported the “true Conservatives” against Mercier’s Parti National. It was the Montreal area that gave the victory to the Conservative party. Before the election Chapleau had demanded more autonomy for his region, including full control of patronage, the selection of candidates, and responsibility for the campaign fund. As a result, Langevin’s influence in the cabinet, the house, and the country was undermined. He was soon in an unenviable position. There was only one Conservative area in the province – Chapleau’s. Most of the ultramontanists, both radical and moderate, were leaving the party. Those who remained faithful were turning to Masson. Nevertheless, Langevin refused first a seat in the Senate and then the lieutenant governorship of Quebec. Desjardins was shocked. “If Langevin had two cents’ worth of patriotism,” he wrote to Masson in March 1887, “he would agree to go . . . to the Senate. . . . He has exactly what is needed to fill that position suitably. . . . But no, his wretched egotism, this dream of having the leading role in the House of Commons and in the country, makes him persist to the point of madness and almost of treason in a stand that holds nothing but ridicule for him and humiliation and enfeeblement for us.”

And so Langevin stayed at public works, claiming in his “Notes intimes” that this was where Macdonald hoped to keep him “in the interests of the party and of the country,” even if he offered him something else. It seems certain, however, that Langevin, watching Macdonald grow older and feebler, dreamed of becoming prime minister of Canada, returning to the fantasy he had cherished at the outset of his career and had at the time revealed to his brother Edmond. But his ambition played into the hands of his opponents.

In his newspaper L’Événement (Québec), Tarte, perhaps with the encouragement of Chapleau himself, used the McGreevy affair to destroy Langevin’s reputation and political future. Robert McGreevy, after a quarrel over money with his brother Thomas*, disclosed to Tarte the unscrupulous deals made by Thomas, who was a member of parliament, provincial treasurer of the Conservative party, and an intimate friend of Langevin, sharing his house and office in Ottawa. Langevin’s honesty was called in question, along with that of his friend. Yet in the election of 5 March 1891, while charges connected with the McGreevy scandal were piling up, Langevin won the two ridings of Trois-Rivières and Richelieu by comfortable majorities. Under the circumstances these victories were astonishing, especially since the province went over to the Liberals. Tarte was not upset by Langevin’s success. He wrote to Wilfrid Laurier* on 13 March: “We are going to drown Langevin in the sea of mud in which I see McGreevy already falling. If there is anything that can kill the government, it is this affair, believe me.” They struck McGreevy to get at Langevin. And the blow hit home.

In June 1891 John Joseph Caldwell Abbott* succeeded Macdonald. He asked Langevin to give up his portfolio, promising to make him lieutenant governor of Quebec. On 11 August Langevin stepped down as minister of public works. But it was Chapleau, himself under attack, who went to Spencer Wood as lieutenant governor in 1892. Devastated by events, Langevin left the public arena when the 1896 election was called and resigned himself, in Chapleau’s malicious words, to living at Quebec “behind his drawn curtains on Rue Saint-Louis.” This retirement went on for ten years. He died on 11 June 1906 and was buried at the Hôtel-Dieu in Quebec beside Lady Langevin.

It is not the custom in parliament to mention the deaths of former members of the government. But at the request of Conservative leader Robert Laird Borden*, Prime Minister Laurier made an exception. Even though Langevin’s political career ended in utter disgrace, it was indeed outstanding by reason of its long duration and its intensity. It was the career of an intelligent, ambitious, loyal, and obstinate man, who contributed to the birth and development of Canada as a Father of Confederation, a pillar of the Conservative party, and a cabinet minister for nearly 30 years. It also helps to shed light on 50 years of Canadian and Quebec history.

[Hector-Louis Langevin is the author of a 170-page documentary account of Canada prepared for the universal exposition held in Paris in 1855, Le Canada, ses institutions, ressources, produits, manufactures . . . (Québec, 1855), and of a legal work, Droit administratif ou manuel des paroisses et fabriques (Québec, 1863; 2e éd., 1878).

Langevin also wrote “Notes intimes,” a 209-page manuscript which is in the possession of Mme Rachel Cimon (Quebec). The most important archival material concerning him is found in the Famille Langevin coll. at ANQ-Q, P-134. A detailed list of other archival repositories, printed sources, newspapers, studies, and periodicals containing information on Langevin can be found in the author’s book, Hector-Louis Langevin: un Père de la Confédération canadien (Québec, 1969). a.d.]

Cite This Article

Andrée Désilets, “LANGEVIN, Sir HECTOR-LOUIS,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 20, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/langevin_hector_louis_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/langevin_hector_louis_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | Andrée Désilets |

| Title of Article: | LANGEVIN, Sir HECTOR-LOUIS |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | January 20, 2025 |