Source: Link

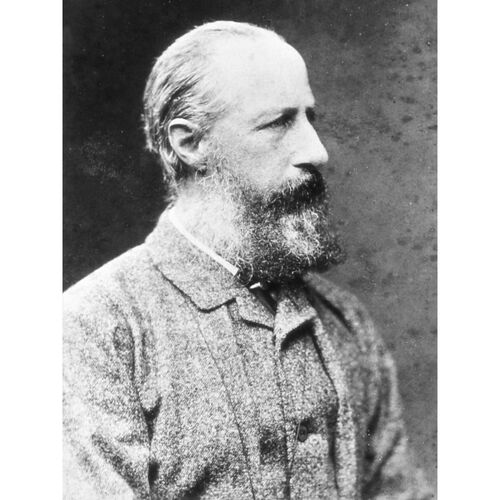

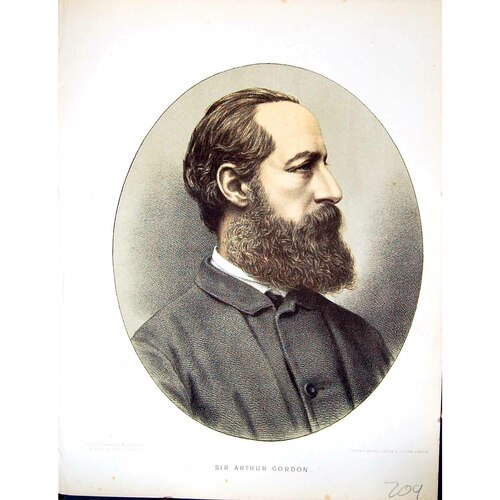

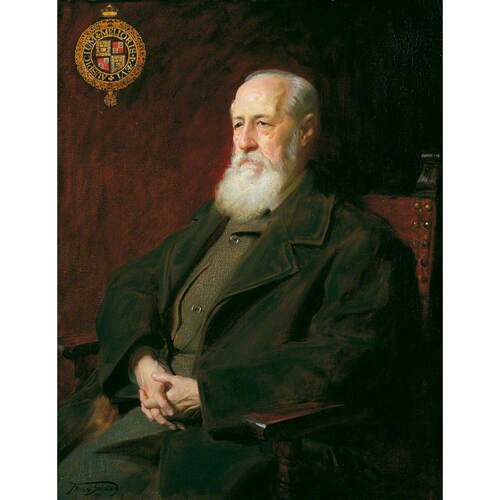

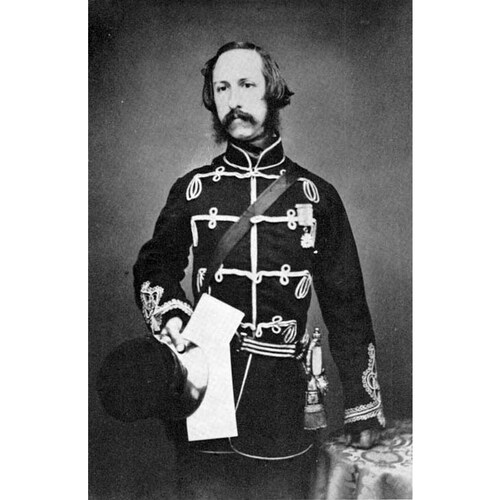

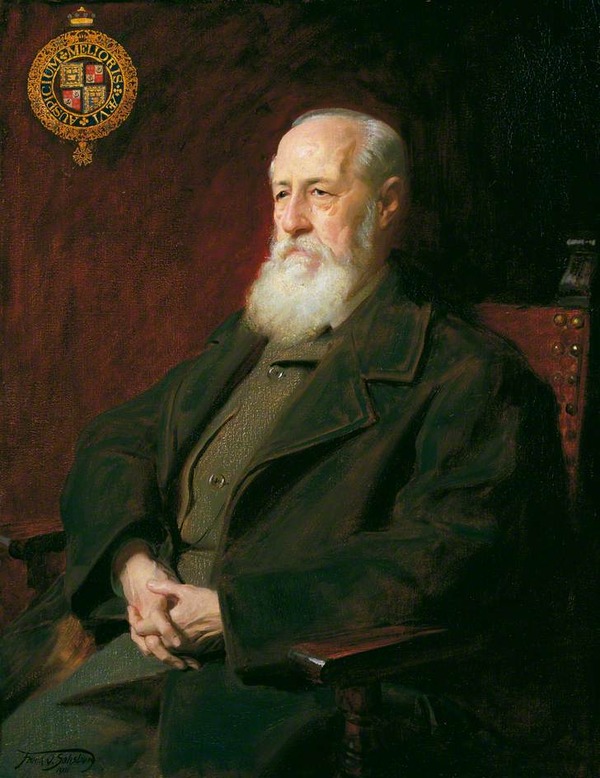

GORDON, ARTHUR HAMILTON, 1st Baron STANMORE, lieutenant governor; b. 26 Nov. 1829 at Argyll House, London, England, youngest son of George Hamilton-Gordon, 4th Earl of Aberdeen, and Harriet Douglas, widow of James Hamilton, Viscount Hamilton; m. 20 Sept. 1865 Rachel Emily Shaw-Lefevre in London, and they had a daughter and a son; d. 30 Jan. 1912 in Chelsea (London), England.

Considered too delicate for public school, Arthur Gordon received an uneven education at home. After a year at a preparatory school near Brighton, he went up to Trinity College, Cambridge, in the autumn of 1847. There he became an active and exemplary student. He took his ma degree in 1851, and influenced by his friendship with Alfred Barry, later primate of Australia, he decided to study for holy orders.

The question of a career had engaged Gordon’s mind for some time. In 1845 he had written to his father, “I feel . . . an excessive desire to be eminent. . . . My idea – one that has occupied me for nearly 3 years . . . is this. To emigrate to Canada . . . our most important [colony]. . . . Though not able to do so in England I might perhaps lead a Canadian parliament.” In 1852 Lord Aberdeen became prime minister and called Arthur to be his private secretary. From that time until the earl’s death in 1860, father and son were almost inseparable. Gordon enjoyed being at the centre of British politics and formed friendships with members of the cabinet the Duke of Newcastle and William Ewart Gladstone.

He entered parliament in a by-election in 1854 but forfeited his seat in the general election three years later, a loss he regarded as a calamity. However, he was now free to accompany Gladstone as private secretary on his mission to the Ionian Islands in 1858. This experience reawakened Gordon’s interest in the colonies. Lord Aberdeen’s terminal illness prevented any immediate action, and not until after his death could his son take up an appointment. In 1861 the Duke of Newcastle, the colonial secretary, offered him New Brunswick or Antigua. Gordon, who had wanted Trinidad, gloomily supposed he would have to “encounter the Arctic winter” of New Brunswick.

The new lieutenant governor arrived there in October just short of his 32nd birthday. He was agreeably surprised at the extravagance of the autumnal colour. “‘The lot has fallen unto me in a fair ground,’” he quoted. “I had expected stunted vegetation, wild rock, and evident traces of the long cold winter on every object. I find a rich and varied landscape with no outward sign of the rigorous frost now rapidly approaching.” His favourable impression strengthened as the months passed. His official duties allowed him ample time for hunting, fishing, and exploring the province by foot and on horseback. He mingled easily with farmers, backwoodsmen, and natives (among those who shared their legends with him was Gabriel Acquin*), and he experienced a “life and vigour” he had never enjoyed before.

Nevertheless, Gordon, a reluctant bachelor until 1865, was lonely. His aide-de-camp and his private secretary offered some companionship but were not his equals. Only with Chief Justice Sir James Carter* could he form a friendship that did not arouse resentment among provincial officials. Still, it was to be his public, rather than his private life that would cause him grief and dissatisfaction and lead him to wish he had never seen the colony. He was by background and temperament better suited to govern a crown colony than a self-governing one, particularly one marked by political bribery and corruption. In the words of a contemporary, Gordon had a “force and reality of character, a power of intellectual discernment, a habit of sound and independent judgment, and an invariable preference for what was just and pure and true over everything artificial, hollow, or low in tone and aim.” Inevitably clashes would occur.

Gordon’s influence derived from the fact that he represented the imperial government (technically the crown), the source of defence for the colony and of financial power for projects such as railway construction. In a province that prided itself on its loyalist traditions, Gordon, as the queen’s representative and the son of a British prime minister, could be sure of support among both the landed and professional classes and those farmers, woodsmen, and labourers who were descended from loyalist regiments.

Under responsible government, the lieutenant governor’s constitutional powers were diminished but not extinguished. Like his immediate predecessors, Sir Edmund Walker Head* and John Henry Thomas Manners-Sutton*, Gordon was unlikely to concede the right to refuse ministerial advice. Nor would he give up control of the militia, of which he was commander-in-chief. He was still entitled to be kept informed and consulted by his ministers before they reached a decision. He could offer advice, which might or might not be accepted. The lieutenant governor remained the sole medium of official communication with Britain, and his dispatches were not accessible to the colonial government.

The first matter to claim Gordon’s attention was the creation of an efficient defence force. In 1851 the legislature had suspended the militia act, and ten years later the colony’s forces consisted of a handful of regulars and 50 companies of unpaid and untrained militia created by Manners-Sutton on his own initiative. However, with the onset of the American Civil War and pressure from the imperial government for the province to assume some responsibility for its defence, Gordon was able to instigate changes. Following the Trent affair [see Sir Charles Hastings Doyle*] in November 1861, 6,000 British troops arrived in Saint John on their way to Canada. No adequate facilities existed for their reception in the middle of winter, and provincial authorities had had only a few days’ notice. Gordon assumed complete control of the situation, commandeering schools, halls, and the custom-house and arranging for bedding and stoves. The troops were transported to Quebec by horse and sleigh, suffering scarcely a frostbite and no deaths.

The arrival of the troops raised morale in New Brunswick but added little to its defence. As a result of the crisis, provincial politicians were persuaded to pass a new militia act and a vote of £2,000 annually for a defence force. Gordon refused to sanction a bill giving the politicians control of the militia. Drawing on his experience as commandant in Aberdeenshire, he created a force that would play an important role in discouraging Fenian raids on New Brunswick in 1866. His reforms outlasted his administration and established a militia system that after confederation would be called “the best in Canada.”

The major issue with which Gordon had to deal during his term in New Brunswick was the proposed unification of the British North American colonies. His role was long misunderstood by Canadian historians, who regarded him as a proponent of Maritime union and an opponent of a broader scheme. Since his private papers became available in the 1950s, a reassessment of his views and his participation in the negotiations has led to different conclusions. Gordon “fully concurred” with the opinion of Nova Scotia’s lieutenant governor, Lord Mulgrave [Phipps*], who in 1858 had written of the “folly of federation,” but initially he did not so completely agree with Mulgrave’s support of a legislative union of the Maritime colonies. He believed that “the difficulty would be nearly as great as of effecting a real [that is, legislative] union of the whole of [British North America] – the result far less brilliant and . . . far less useful.” Although Gordon came to favour a Maritime union, he continued to support the larger one. Early in 1862 he wrote that “every effort should be made to bring about a union of the three Lower Provinces, or of all with Canada.”

Crucial to the larger goal was a railway linking the Maritime colonies with Canada. Gordon bullied the Executive Council into accepting financial responsibility for the province’s share of the project. In so doing, he had the support of Premier and Provincial Secretary Samuel Leonard Tilley*, but he alienated Albert James Smith*, who resigned as attorney general in 1862. At a railway conference at Quebec in September that year, Gordon worked to bring about an agreement between the colonies. After further discussions in London, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia passed measures ratifying the agreement. However, the Province of Canada failed to do so, in effect repudiating it. The suspicion and resentment felt in New Brunswick and Nova Scotia as a result would prove an obstacle in subsequent negotiations for union.

That Gordon was equally frustrated the Canadians had brought the railway to a standstill is evidence of his wish for unification of all the colonies. Only when such a union appeared to be blocked did he turn his attention to that of the lower provinces, an essential first step, in his view, to a broader federation. Further, he had come to regard the eastern provinces as too small and parochial for the satisfactory working of responsible government. Though he supported this form of government in North America, he felt that politics in New Brunswick had regressed since its introduction in 1848. The Liberal party had lost its reforming zeal. Members of the assembly were largely uneducated and narrow in outlook, with little respect for the institution, and the electorate tolerated a low standard of public morality. After he had observed firsthand the petty and corrupt nature of politics in the province, he came to believe that a united legislature in the Maritime colonies might attract a better class of politician.

Throughout 1863 and 1864 Gordon worked for Maritime union so forcefully that it might well have succeeded had not a strong Canadian delegation at the Charlottetown conference forced discussion of a larger union. Although he was disappointed that unification of the eastern provinces had been brushed aside, he was reassured when Alexander Tilloch Galt* and John A. Macdonald* insisted that they intended a strong central government, with the local legislatures having a subordinate status similar to that of municipalities. Edward Cardwell, the new colonial secretary, informed Gordon, “We all agree in favouring a complete fusion not a federation.” The resolutions passed at the Quebec conference obviously did not provide for such a fusion and left the local legislatures intact. Gordon urged the Colonial Office to insist on changes in favour of a centralized government, but Cardwell now did an about-face and instructed him to “promote the scheme of the Delegates to the utmost of your power.” Although Gordon was willing to acquiesce in a policy he did not support, he could not recommend as beneficial what he considered injurious. He offered his resignation, but it was not accepted.

Gordon and Tilley now faced a difficult decision over the timing of the next election. The premier wanted to postpone it as long as possible in order to prepare voters for federal union, but he did not wish to face a new session of the legislature on the issue. He allowed Gordon to persuade him to choose a date early in 1865, with the result that his confederate government was strongly defeated. Attempts were made by ousted politicians to blame the outcome on the lieutenant governor. Gordon feared that the Colonial Office would also attempt to make him the scapegoat. He had actually looked forward to the re-election of the Tilley government, not least because it would have enabled him to leave the province. He had even accepted the governorship of Hong Kong, where he felt he would have more scope for his talents. Instead he was forced to stay on in New Brunswick and deal with an anti-union government led by his old enemy, Smith, and a colonial secretary and Canadians intent on reversing the decision of the electorate.

In August Gordon returned to England for his marriage with Rachel Shaw-Lefevre, a relationship that was to bring him much happiness. While there he had a painful interview with Cardwell, who insisted on a written assurance that the lieutenant governor would use his influence to promote union. Gordon had already decided to take advantage of deep divisions within the Smith government, whose members held positions on confederation ranging from outright opposition to support of a more centralized union than the Quebec resolutions provided. The government’s policy of promoting railway and commercial connections with the United States quickly became bankrupt. In November the administration suffered the loss of a by-election in York County to unionist Charles Fisher*.

The lieutenant governor now forced Smith to admit that he was not averse to union on principle. The premier agreed to put a resolution favouring union through the legislature, and the speech from the throne in March 1866 warned of an impending change in policy. The Legislative Council, a majority of whose members favoured union, responded with an address strongly supporting the Quebec resolutions. When Smith refused to consult with the Executive Council over Gordon’s proposed reply, which “rejoiced” in the council’s “desire that all British North America should unite in one community,” the lieutenant governor determined nevertheless to deliver it. The ministry was forced to resign and raised a storm over Gordon’s “unconstitutional” action.

In the election that followed, Smith and the anti-unionists tried unsuccessfully to make Gordon’s action an issue. During the campaign the threat of a Fenian invasion of New Brunswick alerted the electorate to the greater security that federation would provide. The unionists won a strong majority, polling about 60 per cent of the vote. Only 6 of the 22 members who had signed a motion of censure against the lieutenant governor were re-elected.

Gordon had faced a difficult administration in New Brunswick, many of his problems having been outside his control. He had successfully prepared for the arrival of troops in 1861, prevented a railway strike and riot in 1862, and improved the militia. The men he had appointed to the judiciary were able and impartial. Though ultimately he had helped to place the colony on the path to confederation, in line with the wishes of the imperial government, Canadians, and the provincial Liberals, he had failed to raise the level of political ability and morality in the province through the abolition of the local legislature. He left New Brunswick in the autumn of 1866 with both relief and regret. He was sorry to leave “its glorious climate, its wild free forest life, and the splendid river.” But he was glad to escape the “thraldom of such a set” as his ministers, who were doubtless equally happy to see him go.

Gordon governed the crown colony of Trinidad until 1870. The following year he was given a knighthood and promoted to Mauritius. He resigned in 1874 to become the first governor of Fiji, which Britain had annexed to protect Fijians from settler exploitation and as a base from which to control abuses in the labour traffic in the Pacific. Although he had once resolved never again to take a post in a self-governing colony, in 1880 Gordon accepted the governorship of New Zealand, while retaining the offices of high commissioner and consul general of the western Pacific. He resigned two years later in disgust at his powerlessness to change the government’s Maori policy. His influence in the Pacific lingered through the work of his successors Sir George William Des Vœux* and Sir John Bates Thurston. In Ceylon (Sri Lanka), which Gordon governed from 1883 until 1890, he achieved great popularity among both Sinhalese and Tamils. The Colonial Office considered that he had “done a great deal” for the colony.

Gordon was lonely and unhappy during his last year in Ceylon. Lady Gordon had fallen ill in December 1888 and died at Malta on the way home. He now longed for England and the company of his children. Though he was approaching 61, he still hoped for a peerage or appointment as viceroy of India. He settled in the Red House at Ascot, which he had purchased in 1879. Created first Baron Stanmore in 1893, he entered the House of Lords, where he played an active role in his last years.

For more information on Gordon’s life the reader should consult the author’s full-length study, The career of Arthur Hamilton Gordon, first Lord Stanmore, 1829–1912 (Toronto, 1964).

Gordon published an account of his Canadian hunting trips in “Wilderness journeys in New Brunswick,” Vacation tourists and notes of travel in 1862–3, ed. Francis Galton (London, 1864), 457–524, also issued in monograph form as Wilderness journeys in New Brunswick in 1862–3 (Saint John, 1864).

British Library (London), Add. mss 49199–276 (Stanmore papers). PRO, CO 54/584, 31 Oct. 1889; CO 188/127; 188/131–32; 188/137; 188/192; CO 189/8–9; PRO 30/48/6/39. Univ. of N.B. Library, Arch. and Special Coll. Dept. (Fredericton), MG H12a (Stanmore papers). J. K. Chapman, “Arthur Gordon and confederation,” CHR, 37 (1956): 141–57. The New Brunswick militia commissioned officers’ list, 1787–1867, comp. D. R. Facey-Crowther (Fredericton, 1984), 111. Roundell Palmer, [1st] Earl of Selborne, Memorials . . . , ed. S. M. Palmer [Franquet, Comtesse de Franqueville] (4v. in 2 pts., London and New York, 1896–98), pt.1, vol.2. W. M. Whitelaw, The Maritimes and Canada before confederation (Toronto, 1934; repr. 1966).

Cite This Article

J. K. Chapman, “GORDON, ARTHUR HAMILTON, 1st Baron STANMORE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 29, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/gordon_arthur_hamilton_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/gordon_arthur_hamilton_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | J. K. Chapman |

| Title of Article: | GORDON, ARTHUR HAMILTON, 1st Baron STANMORE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | March 29, 2025 |