Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

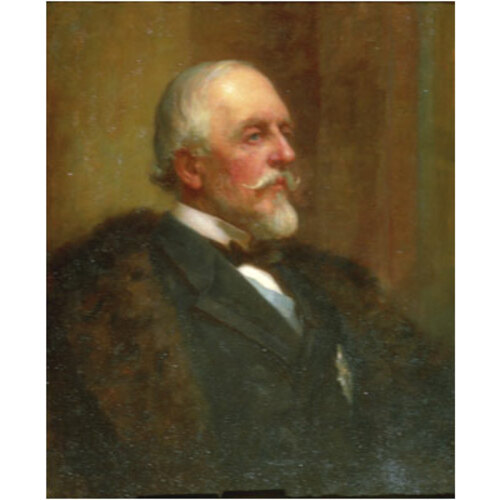

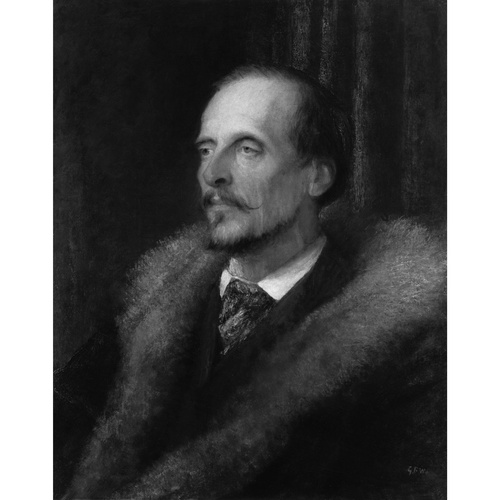

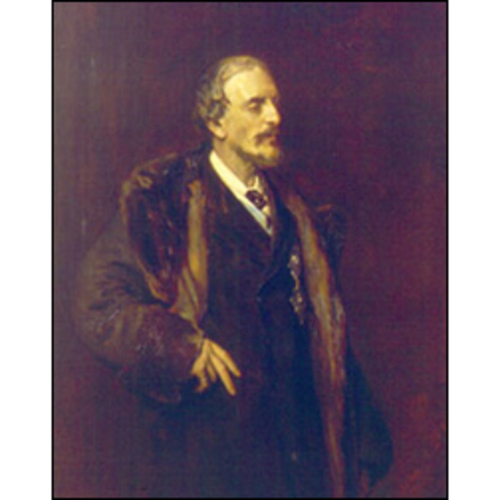

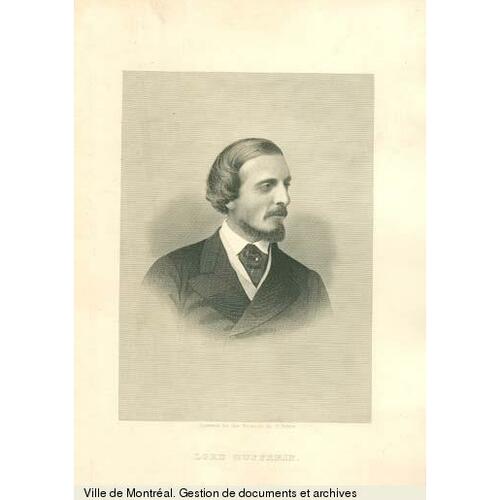

BLACKWOOD (Hamilton-Temple-Blackwood), FREDERICK TEMPLE, 1st Marquess of DUFFERIN and AVA, governor general; b. 21 June 1826 in Florence (Italy), son of Price Blackwood, 4th Baron Dufferin and Clandeboye, and Helen Selina Sheridan; m. 23 Oct. 1862 Hariot Georgina Rowan Hamilton at Killyleagh Castle (Northern Ireland), and they had four sons and three daughters; d. 12 Feb. 1902 in Clandeboye (Northern Ireland).

Frederick Temple Blackwood’s father was a naval officer who came into view of the family title and Irish estate after the deaths of two elder brothers. An only child, Frederick spent much of his youth under the exclusive care of his mother; his father was frequently at sea and the boy soon enough went off to boarding-schools. Certainly the tradition out of which he emerged looked to the intellectuality and artistic virtuosity of his mother’s family – his great-grandfather was the noted statesman and dramatist Richard Brinsley Butler Sheridan. His father, whose influence was perhaps limited to being a model of service to the British empire, died in 1841. Frederick, who succeeded as 5th Baron Dufferin and Clandeboye in the Irish peerage, was then receiving an uneven education at Eton College. He attended Christ Church at Oxford for less than two years, leaving in 1846 without a degree.

Although members of the British aristocracy moved readily into public service, Dufferin may have tended to imperial and diplomatic realms to escape the moral and political dilemmas of being an Irish peer and landlord. In his public writing he both defended the property rights of Irish landholders and anguished over the misery of Irish tenants during the social and political upheavals brought on by the Great Famine. He subsidized his own tenants with guilt money in the form of uneconomic improvements to his estate. Even his marriage took certain Irish realities into account. He assumed the name Hamilton by royal licence in 1862, at about the time of his marriage; he was related to his wife’s family and their union eliminated some long-standing family hostilities.

Dufferin began his career in the charmed atmosphere of Queen Victoria’s intimate court, as a lord-in-waiting (1849–52, 1854–58). His patron, Prime Minister Lord John Russell, also smoothed Dufferin’s entrance (as an English peer, Baron Clandeboye, after the family’s Irish estate) into the House of Lords in 1850. Imbued with all the notions of beneficent empire, and possessing analytical and political skills of a high order, he had his first major diplomatic role in what are now Lebanon and Syria in 1860–61. As the British representative on an international commission, he showed great ability in digesting pertinent information, and then choosing the moments for decisive action to bring some resolution to a state of virtual civil war between Christian Maronites and Muslim Druze. In 1864 he was appointed under-secretary for India; two years later he was shifted to the War Office. These positions helped him refine his administrative and political abilities. His skills and an English earldom, gained in 1871, made him an outside candidate for the Indian viceroyalty in 1872, a post for which he actually had insufficient stature and experience. The possibility did give a sharp edge to what he himself recognized as intense ambition. Instead, Canada, a great but lesser appointment, was given him in March 1872. Dufferin would continue to have his eye on the Indian prize in the years that followed.

Lord Dufferin arrived in Canada on 25 June 1872, succeeding Baron Lisgar [Young*] as governor general. How did a man with considerable and developing public talents fit into the Canadian scene? Dufferin recognized his constitutional limits in Canada, though he strained at them. The ordinary business of his office he performed with considerable skill, especially to the benefit of the Liberal administration of Alexander Mackenzie*, which came into power some 16 months after his arrival. Dufferin sought to place Liberal nationalist aspirations within the boundaries of an expansive and generous empire. His sensibilities in this regard were nowhere more publicly evident than in his personal efforts to save and beautify the fortifications at Quebec City and to have Queen Victoria stamp them with her imprimatur as the sponsor of a new gateway (the Kent Gate). Indeed, the fine terrace overlooking the St Lawrence bears his name. When, in 1874, the Liberals indicated their desire to pursue trade reciprocity with the United States, Dufferin happily expedited the nomination of George Brown* as the leading British commissioner, a position that represented a substantial advance over the role allotted Sir John A. Macdonald* in the Treaty of Washington negotiations of 1871. Dufferin tracked the talks closely, and gave the undertaking the fine tactical and strategic talents which he possessed. After the Liberals decided to establish a military college at Kingston, Ont., in 1874, Dufferin, who in 1868–69 had headed a commission investigating British military education, tried to get, not a patronage appointment, but a leading British officer with strong professional instincts as commandant [see Edward Osborne Hewett*]. That, in his mind, was the best way of affirming Canadian nationality and maintaining British ties. With Mackenzie’s minister of justice, Edward Blake*, whom Dufferin admired but found a pretentious nationalist – petty and overly sensitive – he had serious discussions over the use of the proposed Canadian supreme court as the final court of appeal for Canada. Dufferin saw the court as a means of reducing friction between the dominion and Britain, and thought that judicial appeals to Britain should be sharply limited, but not eliminated as Blake desired.

The governor general held a similar perspective on the difficulty surrounding the Oaths Bill of 1873. During the Pacific Scandal, which precipitated the Conservatives’ downfall later that year, the British government disallowed the bill, which would have permitted parliamentary committees to examine witnesses under oath. In the aftermath, in 1875, Dufferin urged the first major revision of the British North America Act (other than the inclusion of new provinces), to allow the Canadian parliament to follow new British parliamentary practice on examination, rather than being limited to British custom as it stood in 1867. Thus both imperial ties and Canadian national sentiment were served.

Dufferin’s role was crucial too in the resolution of key crises. The Pacific Scandal taught him a great deal about the political constraints on his operations. He had found Macdonald congenial, a man of subtle political ability and statesmanship. Dufferin had some difficulty in accepting Macdonald’s complicity in the scandal, and made his loyalty to the harassed prime minister too evident. Certainly Liberals accused him of favouritism, and raged at his refusal to facilitate their attempt to force Macdonald and the Conservatives out of office. Although the facts as they were later established might have warranted the immediate dismissal demanded by the Liberals, at the time Dufferin was right in not moving precipitately. In the processes of parliamentary committee and commission of inquiry which followed the outbreak of the scandal in April 1873, Dufferin had to act with the utmost discretion to avoid compromising his office. Even so, it would be some time after Macdonald’s fall in November before Mackenzie shed his suspicion that Dufferin had schemed against the Liberals and came to view him with friendly regard.

The governor general soon had a chance to put his special diplomatic and executive-administrative skills to work for the inexperienced Liberal administration which followed the Macdonald regime. Dufferin found Mackenzie, though highly principled, of limited talent and too open to pernicious influence from his cabinet. Consequently he sometimes tried to provide more support and direction than was appreciated.

Dufferin did skilfully manœuvre to remove the burden of dealing with the conviction of Ambroise-Dydime Lépine* in the murder of Thomas Scott* at Red River (Man.) in 1870. His letters on this matter to the colonial secretary, Lord Carnarvon, display a remarkable ability to sift decisive considerations out of misunderstandings and the web of promises provided by Archbishop Alexandre-Antonin Taché* and Lieutenant Governor Adams George Archibald* to Louis Riel* and by implication to his lieutenant, Lépine. Moreover, Dufferin was very sensitive to the intense political pressures on the government. His scorn for Roman Catholic clericalism, rooted in his Irish and high-church Anglican background, influenced but did not poison his outlook on the Red River uprising. The Lépine affair also gave him intellectual distance from the Macdonald administration, which had bungled the matter. The governor general’s commutation in January 1875 of Lépine’s death sentence freed Mackenzie’s administration from the prospect of political rancour in Ontario or Quebec.

Likewise Dufferin played an important role in the confrontation between the federal government and British Columbia over the construction of a transcontinental railway. The issue posed serious dangers to the fledgling confederation and to the British imperial design for North America. Federal efforts to negotiate a reasonable rescheduling of construction and expenditure were rejected by British Columbia, wounded as it was by the sometimes vituperative pronouncements of Liberals about the railway and the province. An attempt at imperial mediation, the Carnarvon Terms, was rejected by the Senate in 1875 over a key element – the construction of the Esquimalt-Nanaimo railway. Dufferin felt his role as federal representative and imperial mediator required direct intervention: during his long official visit to British Columbia in 1876 he managed to balance imperial impartiality with a temperate defence of the Mackenzie government’s position, and so to some extent appeased British Colombian anger [see Andrew Charles Elliott*].

He was less successful in dealing with his Liberal government in Ottawa on his return. He had been warned before his departure not to view his role in British Columbia as ambassadorial or as that of a federal negotiator. Yet Dufferin pressed Mackenzie to compromise with British Columbia, along lines suggested by Lord Carnarvon. The continued narrowness of Edward Blake on this issue, combined with the niggardliness of finance minister Richard John Cartwright*, angered Dufferin, especially because of their influence on the more conciliatory Mackenzie. There was a key misunderstanding: Dufferin thought the sop of $750,000 that had been given to British Columbia was in lieu of the Esquimalt-Nanaimo railway; Mackenzie and Blake felt that it was in lieu of any and all delays in constructing the Pacific railway. The latter interpretation was unacceptable on the west coast. Dufferin believed that Mackenzie and Blake were backtracking on promises and destroying his good work in British Columbia. The three “nearly came to blows” when they met on the matter in November 1876; Dufferin verged on the abusive, and recorded with hostile pleasure that “Mackenzie’s aspect was simply pitiable, and Blake was upon the point of crying, as he very readily does when he is excited.” Fortunately for Dufferin, his display of anger was a useful diplomatic tool in prodding the Liberal leaders to compromise. After the obligatory smoothing of feathers, Mackenzie hesitatingly agreed to a conference in England should the best efforts of the government to expedite the Pacific railway prove insufficient, and Dufferin in conjunction with Carnarvon used this accord to sedate British Columbia. In all of this dealing Carnarvon allowed himself to be guided by Dufferin, as he increasingly did in other Canadian matters. Dufferin was nevertheless displeased with the outcome of his work, and he anticipated the weakening or defeat of the Liberal government as the only way to resolve the problem. At the same time these British Columbian confrontations reaffirmed Mackenzie’s view of Dufferin as an imperial meddler and removed warmth from their relationship. He sharply told the governor general that “Canada was not a Crown Colony (or a Colony at all in the normal acceptation of the term)” and that the dominion “would not be dealt with as small communities.”

The British Columbia tour was the most ambitious and politically sensitive of Dufferin’s official excursions. Large portions of virtually every summer were devoted to such tours. In addition to British Columbia, the viceregal family travelled throughout Quebec, the Maritimes, and Ontario. Dufferin saw these tours as a duty associated with the consolidation of Canada, and thus of the British empire in North America. His visit to the Maritimes in 1873, for example, had the effect of reducing hostility to confederation there, or so it seemed to contemporary observers. He defended the existence of Canadian nationality in North America with humour and assurance (despite his lisp) in speeches in Canada and during his visits to the United States. Empire and nationality were strengthened by his frequent contribution of “Dufferin Medals” for academic or athletic endeavour. His considerable popularity, and his occasional stress on the role of cultural minorities and immigrant groups in Canada, enhanced his inclusive imperialist-nationalist message.

The social and political functions of tours and constant speech-making were supplemented by the social whirl Lord and Lady Dufferin created in Ottawa. Lady Dufferin assumed responsibility for readings and well-attended plays, in which she took leading roles, and she had frequent at-homes at Rideau Hall, their official Ottawa residence. With her husband she presided over large parties and dinners, including a huge costume ball in February 1876. Lord Dufferin, in his more casual entertaining, preferred athletic activities. He skated; he curled; under some pressure from his children he set up a toboggan run, which winter visitors enjoyed. He had the temerity to invite dour Alexander Mackenzie, a man highly dubious about frivolous athleticism, to engage in sports at Rideau Hall. Autumn, winter, and spring were filled with a constant round of such activity, which established a perverse contrast in Ottawa: the Dufferins, lavish, intent on creating a court for the effective functioning of politics; the Mackenzie government, parsimonious, intent on restraint. Some unhappy bickering between the free-spending Dufferins and the Liberal government resulted. Dufferin had to dip into his own wealth to undertake certain pet projects, and he tried with some success to have his official stipend increased. None the less, the Dufferins made Rideau Hall a centre of activity and entertainment at the previously amorphous apex of Canadian political society.

Lord Dufferin’s pursuit of the social and the athletic was also self-indulgent. He loved Charles Dickens because the English author taught “the duty of gaiety and the religion of mirth.” A slightly built man, he had great physical energy and considerable adventurousness: he sailed as often as possible, fished for salmon in remote locales (Lady Dufferin also went on such expeditions), and, on one occasion, went down a Nova Scotia coalmine and picked the coalface. Such adventuring tied his Canadian experience to key events of his youth, among them his visit to a scene of naval bombardment in the Baltic in 1854 and to the Arctic ice-pack at Spitsbergen in 1856, both in the family yacht.

For these reasons and because of the joy he took in his then young family, Dufferin would remember his time in Canada with affection. If his stay there was sometimes an exile, however, so was much of his life. Even at Clandeboye, in youth and retirement, he was not entirely at home, though his tenants generally viewed him with loyalty. He had with bitter humour recognized the possibility of his assassination as an Irish landlord in 1847. By 1876 he had sold most of his Irish land because of the risks of changing political circumstance.

Dufferin’s term as governor general expired in 1878, and he was succeeded by the Marquess of Lorne [Campbell*]. When he left Canada in October of that year, the time was not opportune for appointment to India – the Conservatives were in power in Britain – and he accepted the Russian ambassadorship from the Disraeli government in 1879. By doing so he weakened his claim to patronage from the Liberal Gladstone regime, which replaced it. Instead of India in 1880, Dufferin received a further term in Russia. He complained somewhat resentfully that his years in Canada and Russia “might have deserved a better reward than a further term of exile in an Arctic climate.” Afterwards, in 1881, he went to Turkey as ambassador. A few months later a crisis of governance and finance occurred in Egypt, technically part of the Ottoman empire, but where, as well as the Turks, the French, the British, and others also had interests. He was closely involved in the international machinations which followed and which led to the British invasion of Egypt under Sir Garnet Joseph Wolseley* in 1882. Dufferin was then appointed British commissioner to investigate the Egyptian situation and recommend solutions. His report was widely considered a magnificent analysis, though he later was accused of disguising the extent of division in Egypt.

Dufferin’s work there may have been decisive in gaining him the Indian viceroyalty (1884–88). It was in India that he could most fully indulge his penchant for executive action under imperial aegis. In Canada he had seen himself as merely oiling the cogs of government; in India he could, and did, order the invasion of Burma, a constant thorn in the side of Victorian India. Despite the pre-eminence of the Indian viceroyalty, when Queen Victoria conferred a marquessate on Dufferin in 1888, he wanted a Canadian link, as marquess of “Dufferin and Quebec.” Political considerations forced him away from that and to “Dufferin and Ava,” Ava being an ancient Burmese capital. Dufferin finished his career of public service with prestigious ambassadorships at Rome (1889–91) and Paris (1891–96).

After his retirement on 13 Oct. 1896, some savage shocks awaited him. His eldest son died in the South African War in 1900. Financial crisis closed in on Dufferin at the same time. He had never been fiscally prudent. In selling much of his Irish land he had chosen liquidity in capital. Some major investments in the London and Globe Finance Corporation were speculative and unwise, and he led others into similar straits through his chairmanship of the company, which he had undertaken in 1897. Heavy losses were incurred, and in 1901 he shouldered much of the public blame. By the end of the year he was seriously ill. Dufferin died on 12 Feb. 1902 at Clandeboye, where he was buried.

In Canada Dufferin was publicly well liked. His popularity grew out of his imperial assurance, his affirmation of Canadian nationality, his sense of compromise, and his charm and wit. When combined with his wife’s quiet ambitions and effective social skills, his abilities allowed them together to create a viceregal court. A Canadian political and bureaucratic élite took form socially under their cultivation. In the private politics of the Privy Council, where Dufferin clearly hoped to be most usefully employed, his sometimes autocratic imperial impulses warred with his diplomatic talents, and occasionally led to confrontation. “The Governorship of a Colony with Constitutional advisers does not admit of much real control over its affairs, and I miss the stimulus of responsibility,” he acknowledged early in his Canadian career. That stimulus he later had in India. Dufferin’s power in Canada lay in his personal and imperial influence, which was great, and sufficed.

[There is substantial material on Lord Dufferin’s stay in Canada in the Mackenzie (MG 26, B) and Macdonald papers (MG 26, A), both at the NA, and in the Dufferin papers at the Public Record Office of Northern Ireland, Belfast. The portion of this collection relating to Canada is available on microfilm at NA, MG 27, I, B3. Official dispatches and correspondence are to be found in the records of the Colonial Office (PRO, CO 42; available on microfilm at the NA). This series also contains Dufferin’s informal correspondence with Lord Carnarvon, which has been published with careful commentary in Dufferin-Carnarvon correspondence, 1874–1878, ed. C. W. de Kiewiet and F. H. Underhill (Toronto, 1955; repr. New York, 1969). A collection of Dufferin’s public addresses during his tenure in Canada was published as Speeches of the Earl of Dufferin, governor general of Canada, 1872–7878 – complete (Toronto, 1878); a selection of Canadian speeches also appears in Speeches and addresses of the Right Honourable Frederick Temple Hamilton, Earl of Dufferin, ed. Henry Milton (London, 1882).

Biographies include: Sir Alfred Lyall, The life of the Marquis of Dufferin and Ava (2v., London, 1905); C. E. D. Black, The Marquess of Dufferin and Ava . . . diplomatist, viceroy, statesman (London, 1903; also issued in Toronto the same year), especially strong on India; Sir Harold George Nicolson’s brilliant memoir of his uncle by marriage, Helen’s tower (London and Toronto, 1937); and the entry in the DNB. Two comprehensive but biased contemporary studies of Dufferin’s Canadian career provide speeches, dispatches, and context: George Stewart, Canada under the administration of the Earl of Dufferin (Toronto, 1878), and William Leggo, The history of the administration of the Right Honorable Frederick Temple, Earl of Dufferin . . . late governor general of Canada (Montreal and Toronto, 1878).

The social activities of Lord and Lady Dufferin are detailed not only in these two volumes but also in [H. G. R. Hamilton Blackwood,] Marchioness of Dufferin and Ava, My Canadian journal, 1872–8: extracts from my letters home, written while Lord Dufferin was governor-general (London, 1891). His western Canadian tour is chronicled in two contemporary accounts, both published in London in 1877: Journal of the journey of his excellency the governor-general of Canada from Government House, Ottawa, to British Columbia and back, written anonymously by a member of Dufferin’s party, and The sea of mountains; an account of Lord Dufferin’s tour through British Columbia in 1876, a two-volume work by western journalist Frederick Edward Molyneux St John.

Dufferin’s youthful adventures are partially chronicled in his own words in Letters from high latitudes; being some account of a voyage in the schooner yacht “Foam” . . . to Iceland, Jan Mayen, and Spitzbergen in 1856 (London, 1857), which went through many editions. Of particular note are the Canadian editions published during his tenure as governor general in both English and French: A yacht voyage: letters from high latitudes . . . (Toronto, 1872) and Un voyage en yacht: lettres de hautes latitudes; récit d’un voyage fait en 1856, sur le yacht le “Foam” . . . , T.-P. Bédard, trad. (Montréal, 1876). b.f.]

Cite This Article

Ben Forster, “BLACKWOOD (Hamilton-Temple-Blackwood), FREDERICK TEMPLE, 1st Marquess of DUFFERIN and AVA,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 1, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/blackwood_frederick_temple_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/blackwood_frederick_temple_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | Ben Forster |

| Title of Article: | BLACKWOOD (Hamilton-Temple-Blackwood), FREDERICK TEMPLE, 1st Marquess of DUFFERIN and AVA |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | April 1, 2025 |