Source: Link

FAIRWEATHER, MARION (Stirling), teacher, missionary, and physician; b. 14 Oct. 1846 in Bowmanville, Upper Canada, daughter of David Fairweather, a shopkeeper, and Anna ------; m. 25 Sept. 1888 Charles Stirling in Agra, India; they had no children; d. 28 Feb. 1923 in San Leandro, Calif.

The youngest of the four daughters of Scottish-born parents, Marion Fairweather attended McGill Normal School in Montreal, where she received an elementary-level teaching diploma (1869) and a model-school diploma (1872). She taught in Bowmanville in the interim. In 1872 she wrote to the Foreign Missions Committee of the Canada Presbyterian Church to enquire about appointments for herself and Margaret Rodger, a fellow graduate of McGill Normal School. Because the FMC did not yet have an overseas field, it corresponded with Presbyterian mission boards in Scotland and the United States about a placement for them. It also arranged for them to spend some time at a Presbyterian institution, the Ottawa Ladies’ College, perhaps as much to monitor their fitness for service as to prepare them for it. By the autumn of 1873 it had been decided that Fairweather and Rodger should begin work in an American Presbyterian mission in northern India. On Christmas Eve they arrived in the city of Allahabad.

Notwithstanding some peremptory letters from Fairweather to the FMC prior to their departure, she and Rodger seem to have left Canada with its full approval. “As you are our pioneers,” FMC secretary Thomas Lowry wrote, “we must be guided very much in our future plans by the information which we may get from you and from other sources respecting the state of affairs in the place to which you have gone.” Unlike the taciturn Rodger, Fairweather responded with alacrity to this letter and the opportunity it presented. She urged her American colleagues to advise the FMC on a location for a Canadian mission, and she endorsed their suggestion of Indore, in Central India. Early in 1877, two years after the union that created the Presbyterian Church in Canada, Indore became the site of the church’s first mission station in India when Fairweather and Rodger began work there with its official founder, the Reverend James Moffat Douglas*. Arguably the most important figure in the mission’s establishment, the supremely confident Fairweather acted first as Douglas’s mentor and then as his closest colleague.

After learning of his appointment, she had written to him, to the FMC, and to the church’s newly established Woman’s Foreign Missionary Society (Western Division) [see Marjory Laing*] about the types of work the mission should take up and her “plans” for appointees. She had begun as well to recruit a group of Indian Christian workers to accompany her to Indore. There she worked with Douglas to establish a press and, like him, she attempted to convert high-caste Indian men. She also engaged in the more conventional tasks of a woman missionary in India: school work and visiting zenanas. The latter involved calling on secluded Muslim and high-caste Hindu women, and trying to introduce the gospel through such subterfuges as lessons in reading and needlework. The agency among women about which she became most enthusiastic was medical work. While serving with the Americans, she had come to know their pioneer female medical missionary, Dr Sara Seward. Impressed by the drawing power of her work, especially among elites, Fairweather strongly commended similar practice to FMC convenor William McLaren (MacLaren), in the hope perhaps that the church would finance her training.

By the end of 1879 the mission would have two stations and a Canadian staff of three single women and two ordained men with their wives. At the outset the FMC had not provided formal regulations for the staff, and in this context Fairweather recognized no constraints on her role other than those inherent in being unordained. Her expansive approach aroused resentment among the Canadian workers, while her working relationship with Douglas became a subject of gossip among the Indian staff. In October 1879 the FMC recalled her to Canada without first asking for her version of the conflicting, sometimes bizarre reports about her and Douglas that it had received from the mission. Letters from ordained and secular Europeans in India uniformly testified to her ability and drive, but they could not save her career. Along with the praise, and scorn for the gossip about sexual improprieties, the letters made it clear that she did not fit the conventional image of a submissive Victorian woman, much less that of a lady missionary. An ordained Scottish missionary observed that she was “far indeed from the meekest of women,” while a former Church of England chaplain told her “I should have been proud if a sister of mine had had your zeal and ambition, but I should not have let her try to convert native gentlemen.” In June 1880, following a meeting with Fairweather (held only at her request), the FMC formalized its decision to remove her from the mission staff. In having to deal with conflicts in a new and distant mission, the FMC was by no means unique, but its arbitrary response was somewhat unusual.

Fairweather’s efforts to have the FMC reappoint her or help her find another posting came to nothing, as did her vague threat to take legal action. Yet she did not obligingly fade into obscurity. Between 1880 and 1884 she contributed three series of articles on India to the Canada Presbyterian (Toronto). For the most part, she forbore using them to present her version of the mission’s recent troubles and she kept her tendencies towards self-promotion in check. Collectively, the articles leave the impression of an able, articulate woman whose cultural horizons had been broadened by her residence in India and who had come to hold a more enlightened view of the missionary’s task there. In a small way they may also have helped finance the medical studies that preceded Fairweather’s return.

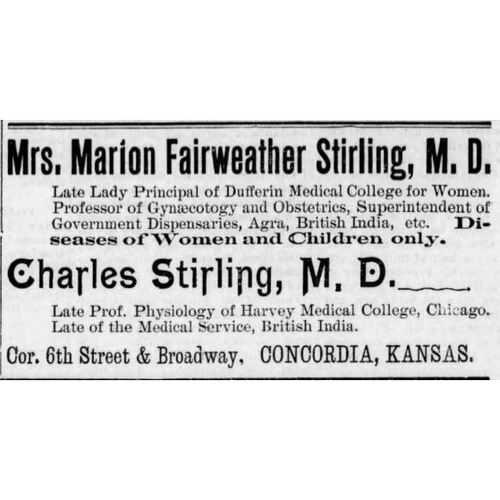

Beginning in the autumn of 1880, she spent two years in nurses’ training at Charity Hospital, on Blackwell’s (Welfare) Island in New York City. She then studied to become a doctor at the Woman’s Medical College of Chicago; following her graduation in 1885 she practised briefly to obtain money for supplies. Upon arriving in Agra in January 1887, she worked for the Countess of Dufferin’s Fund. Inaugurated in 1885 by the wife of the viceroy, Lord Dufferin [Blackwood*], it financed medical treatment and training for Indian women. A historical account of graduates of the Woman’s Medical College claims that Fairweather began providing services soon after her arrival and started a medical school, which quickly had 50 students. Her stay, however, was short. In September 1888 she married Charles Stirling, an Englishman who had graduated earlier in the year from the College of Physicians and Surgeons, Chicago. The couple moved to Delhi, where Fairweather continued working for the Dufferin fund, but Charles’s health failed and they returned to the United States.

Details of Fairweather’s life thereafter are sketchy. She lived for a time in Chicago, listing electro-therapeutics as her speciality, and she and her husband obtained formal certification to practise medicine. It is not clear whether Allen, Charles’s son from a previous marriage, lived with them. By 1914 they both had practices in Oakland, Calif., and they were there when Charles died in 1918. Just two years before her own death Marion moved to San Leandro, where, her obituary reported, she had once owned “considerable property.” An initiator to the end, she had opened a sanatorium, which was “doing well” until she succumbed to pneumonia. Like her “beloved husband,” she was cremated.

Marion Fairweather’s background resembled that of many of the Canadian Protestant women drawn to foreign missionary service, but her subsequent career did not. Like her, many female missionaries challenged the norms of Victorian womanhood, even as they paid lip-service to those norms. Fairweather, however, was remarkable for the degree to which she took unwomanly initiatives and defied the conventions of separate missionary spheres. When her unorthodox conduct in India led to her recall, she redirected her energies and achieved a second, atypical career.

[Materials concerning the lives of Marion Fairweather and Charles Stirling in Oakland, Calif., including local obituaries, California Crematorium records, and the details of their medical qualifications, were supplied to the author by the Oakland Public Library’s Oakland Hist. Room. Information on the Fairweather family of Bowmanville, Ont., was drawn from indexes to the Bowmanville News and the Canadian Statesman (Bowmanville) in the Bowmanville Public Library. r.c.b.]

MUA, RG 30, McGill Normal School records. UCC-C, Fonds 122/1, 79.185C, file 1-1; Fonds 122/8, 79.195C, files 5–9. Canadian Statesman, 22 March 1923. Canada Presbyterian (Toronto), new ser., 1 (1877–78): 611–12. Ruth Compton Brouwer, “Far indeed from the meekest of women: Marion Fairweather and the Canadian Presbyterian mission in Central India, 1873–1880,” in Canadian Protestant and Catholic missions, 1820s–1960s; historical essays in honour of John Webster Grant, ed. J. S. Moir and C. T. McIntire (New York, 1988), 121–49; New women for God: Canadian Presbyterian women and India missions, 1876–1914 (Toronto, 1990). Presbyterian Record (Montreal), 2 (1877): 15–26, 155–56.

Cite This Article

Ruth Compton Brouwer, “FAIRWEATHER, MARION (Stirling),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 1, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/fairweather_marion_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/fairweather_marion_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | Ruth Compton Brouwer |

| Title of Article: | FAIRWEATHER, MARION (Stirling) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2005 |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | January 1, 2026 |