Source: Link

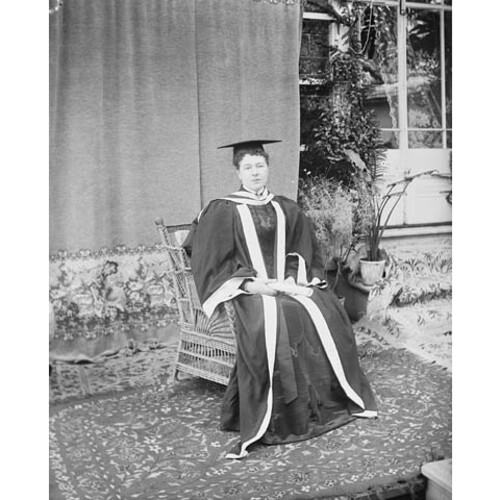

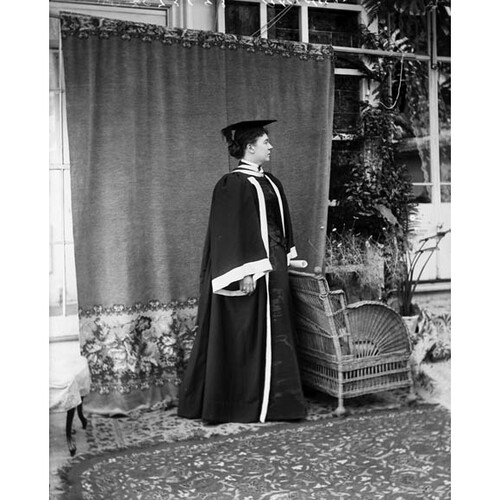

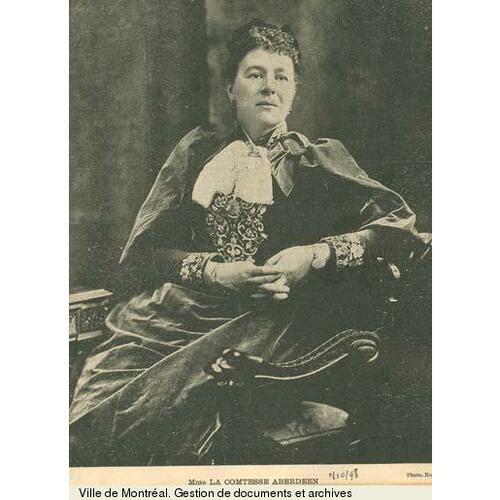

MARJORIBANKS, ISHBEL MARIA (Hamilton-Gordon (Gordon), Countess of ABERDEEN and Marchioness of ABERDEEN and TEMAIR), viceregal consort, feminist, social reformer, and author; b. 14 March 1857 in London, England, daughter of Dudley Coutts Marjoribanks and Isabel (Isabella) Hogg; m. there 7 Nov. 1877 John Campbell Hamilton-Gordon, 7th Earl of Aberdeen, and they had three sons and two daughters, one of whom died in infancy; d. 18 April 1939 in Aberdeen, Scotland, and was buried in the family cemetery at Haddo House, Aberdeenshire.

Ishbel Marjoribanks is a leading example of what historian Amanda Andrews has called the “great ornamentals,” viceregal “new women” who claimed leadership in good works throughout the British empire. The ambitious and upwardly mobile Hogg and Marjoribanks families, with fortunes made in India, banking, and brewing, directed their sons and daughters into marriages with members of Britain’s Conservative and Liberal elites. Forbidden by her father from attending Girton College, Cambridge, the pioneering university option for women, the talented Ishbel was educated at home and groomed in French, German, music, and art; she was presented at court just before her 18th birthday. Kinship links remained important, but she went beyond expectations in embracing the evangelical Protestantism of her mother, her uncle the philanthropist Quintin Hogg, and politician and family friend William Ewart Gladstone. By her teens Ishbel was teaching Sunday school to working-class boys in London’s East End and to tenants’ children on the Highland estate of Guisachan, which her father had purchased in the mid 1850s. Despite early recognition of her intellectual and organizational abilities, Ishbel remained often uncertain and nervous. In particular, she was self-conscious about her looks (especially her size) and her lack of a formal academic education, which she attempted to make up for by reading widely. Her sensitivity further encouraged her lifelong compassion for the unfortunate and balanced her compulsion to lead. Fortunately, her essentially sunny temperament, personal warmth, and great energy inspired admiration and affection and helped her survive the misogyny often directed at talented women.

Her philanthropic sympathies enhanced the attractions of the similarly evangelical Earl of Aberdeen, who succumbed after a three-year on-and-off courtship. Their marriage in St George’s Church, Hanover Square, was presided over by the archbishop of Canterbury, a friend of both families. The couple’s narrow Protestantism would be liberalized in the 1880s under the influence of Henry Drummond, the charismatic Scottish theologian who reconciled evolution and Christianity in a doctrine of social altruism. The union proved to be a loving one, becoming a feminist ideal of progressive activism and companionship. An Egyptian honeymoon saw the Aberdeens dispensing medical supplies and rescuing Sudanese children from slavery and a young Christian convert from his Muslim family.

On the Haddo estate in northeast Scotland the young countess guaranteed the lineage, giving birth to five children between 1879 and 1884. She also discovered the costly pleasures of renovation (Haddo House eventually became a treasure of the National Trust for Scotland) and the needs of rural and domestic labourers. With her husband’s support, she built upon the practical philanthropic programs initiated by her mother-in-law. Her respectful relationship with the lower classes took form in the Haddo House Club for household staff and the Haddo House Young Women’s Improvement Association, originally intended for servant girls in the district and later expanded into the Onward and Upward Association, which spread throughout Scotland and beyond. These organizations (whose names would vary over the years) were intended to bring together working-class women and their mistresses in educational and recreational programs. Lady Aberdeen’s magazine for women, Onward and Upward (Aberdeen and London, 1890–1920), and its supplement for children, Wee Willie Winkie (nominally edited by her daughter, Marjorie Adeline), disseminated the messages of social improvement, spiritual renewal, and social stability and partnership. School meals and health services for tenants on the estate served the same ends.

The countess had also extended her efforts to the Aberdeen Ladies’ Union (ALU), becoming its first president in 1883. The ALU sought to advance the welfare of local women working in factories, fish-processing plants, private homes, and hotels. It also assisted their emigration to the colonies, especially Canada. The same decade saw her assume the presidency of the Edinburgh Association for the University Education of Women, which was committed to preparing members of her sex for responsible citizenship. In London, where the couple spent parliamentary seasons, she lent her weight to the Women’s Trade Union Association’s successful campaign for female factory inspectors in the 1880s and the pro-union efforts of its successor, the Women’s Industrial Council, in its attempts to improve conditions for women employed in the trades. In 1888 Lady Aberdeen became president of the Society to Promote the Return of Women as County Councillors (later the Women’s Local Government Society), which promoted female candidates in municipal elections. In these endeavours she would remain a maternal feminist, who rejected any idea of wars between the sexes: maternally minded women worked hand in hand with responsible men such as her husband. Her activism in the 1880s provided her with critical experience in public speaking and effective organization. However, while she soon excelled in these areas and was regularly hailed as proof of women’s potential, she also made enemies, particularly among those impatient for the implementation of women’s rights. As a result, she often felt intimidated and emotionally drained.

A passionate admirer of Gladstone, Lady Aberdeen encouraged her husband’s move from the Conservative Party to the Liberals by 1880. Her ecumenism was confirmed during his term as lord high commissioner to the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland between 1881 and 1885, when the couple attempted to bring together the leaders of the established and Free churches. Lord Aberdeen’s appointment as lord lieutenant (viceroy) of Ireland in 1886 introduced a lasting passion. Initially apprehensive, Lady Aberdeen soon threw herself into her new role and embraced a romantic vision of what she saw as the essential Celt. Dressing herself and her children in locally made textiles, she championed home industries.

The defeat of the Liberals that year ended Lord Aberdeen’s viceregal tenure and led to a world tour in 1886–87 that raised the countess’s hopes for a reformed empire in which progressive elites would further social peace. She returned to her many activities in Britain, promoting the welfare of women and children and addressing large congresses in Aberdeen and Birmingham. But in October 1889 she suffered a collapse and was ordered by her doctor to rest. The following year the Aberdeens and their children set out on an extended visit to Canada. While in Montreal, they dined with railway builder Sir Donald Alexander Smith* and met Oblate missionary Albert Lacombe*, whom Lady Aberdeen charmed when she conversed with him in French, to the surprise of the other guests. After a stay at Highfield House in Hamilton, Ont., and visits to Toronto and Ottawa, the couple travelled to the west coast by train. In Manitoba they met with immigrants from northeast Scotland whom they had assisted. During a stop in Winnipeg on the way back east, the countess, together with local women, initiated the Aberdeen Association [see Margaret Vallance*] to provide reading material for isolated settlers in the northwest. A return trip to North America in 1891 brought the Aberdeens to Guisachan Ranch, in British Columbia’s Okanagan valley, which they had purchased the previous year and where it was hoped Lady Aberdeen’s remittance-man brother Coutts Marjoribanks might redeem himself; they went on to buy the larger Coldstream Ranch [see Charles Frederick Houghton*]. These two journeys form the basis of her first book, Through Canada with a Kodak (Edinburgh, 1893), illustrated in part with her own photographs. She largely dismisses the Chinese she encountered in the west, seeing them as sojourners rather than permanent settlers like the Europeans. Several chapters are devoted to the traditions of indigenous peoples; as historian Marjory Harper comments, Lady Aberdeen was simultaneously attracted by romantic images of natives and repulsed by the harsh reality of their lives.

On the couple’s return to Britain, she increasingly focused her efforts on the English and Scottish women’s Liberal federations. She joined moderates such as Catherine Gladstone and her own sister-in-law Lady Fanny Octavia Louisa Marjoribanks (later Lady Tweedmouth) and suffragists such as the Countess of Carlisle and Priscilla Bright McLaren in modernizing the party and making claims for women’s public duties. But fearful of antagonizing members of the male elite, she was cautious about advocating parliamentary (as opposed to local) suffrage. As she struggled to find a middle ground, some condemned her as too radical, while others judged her too timid.

Gladstone’s electoral victory in 1892 and her husband’s imminent appointment as governor general of Canada ended Lady Aberdeen’s first presidency of the women’s Liberal federations. At the World’s Columbian exposition in Chicago the following year, she opened the “village” she had organized to promote Irish industries. More significantly, she was elected to the presidency of the International Council of Women (ICW), founded by American suffragists in 1888 and holding its first quinquennial gathering during the fair. Seen as a safe international candidate, the trilingual countess was to bring feminism in from the wilderness. In order to maximize its appeal, the ICW held back from suffrage.

In Toronto, soon after the viceregal couple’s arrival in the dominion in the autumn of 1893, she took up the challenge she had been given. A number of Canadian women, including Adelaide Sophia Hoodless [Hunter*], had been in Chicago during the ICW meetings and were eager to start their own group. At its inaugural congress in Toronto in October 1893, Lady Aberdeen accepted the presidency of the National Council of Women of Canada (NCWC). Its pledge to follow the golden rule (“Do unto others as you would have them do unto you”) and its ecumenism tempted women eager for a non-partisan voice in a divided nation. The Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, the country’s largest women’s society, deplored its new rival’s refusal to endorse Protestantism and temperance, but the support of the Women’s Art Association and the Girls’ Friendly Society helped confirm the NCWC’s respectability. Of equal or greater significance was the council’s alliance with the Dominion Women’s Enfranchisement Association and its hard-pressed suffragists. By the time Lady Aberdeen left Canada in 1898, the NCWC had become the nation’s most powerful feminist group, with local councils in every region except the far north. In an era of intense political conflict, it was highly unusual in associating francophones and anglophones, and Roman Catholics, Protestants, and Jews, though indigenous peoples and other racial minorities remained largely unrepresented.

Lady Aberdeen’s second major contribution in Canada grew out of the work of the NCWC. This was the creation in 1897, despite the opposition of many male medical professionals (and, initially, some trained nurses), of a nationwide public-health service, the Victorian Order of Nurses (VON) for Canada. Charlotte MacLeod, a Canadian-born nursing instructor then working in Massachusetts, was appointed chief superintendent. Lady Aberdeen became the organization’s president, a tradition followed by wives of later governors general. Strategically invoking the sovereign, the VON affirmed women as active citizens in a northern nation, a female equivalent of the North-West Mounted Police. In May 1898 four nurses, accompanied by journalist Alice Matilda Freeman (Faith Fenton), were sent to the Yukon territory to minister to prospectors during the gold rush there. This mission, launched with great fanfare and reported in the Toronto Globe and Vancouver Daily World, drew much favourable attention to the new organization.

Individual women could also thank Lady Aberdeen for her support. Inviting Adeline Foster [Davis*], the wife of finance minister George Eulas Foster and the innocent party in a divorce, to a concert at Government House in December 1893 broke the ostracism that Mrs Foster had faced in Ottawa society. When pioneering female lawyer Clara Brett Martin* sought legislative changes that would allow her to be admitted to the Law Society of Upper Canada, she won the help of the countess and the NCWC.

During her stay in Canada, Lady Aberdeen entered enthusiastically into its social life. She organized skating and tobogganing parties and learned to dance in the Canadian fashion. The series of historical balls she orchestrated in Ottawa, Toronto, and Montreal made women and Europeans central to the image of the nation as an imperial rival to the United States; the indigenous figures the events incorporated advanced the same concept. A May Court Club was started to introduce the capital’s elite young women to the idea of service. Lady Aberdeen’s ambitious plans for Ottawa, though never realized, anticipated the work of the National Capital Commission. These years also brought her several distinctions, including, in 1897, the first honorary degree given to a woman by Queen’s College in Kingston, Ont., and her selection as convocation orator at the University of Chicago.

Like earlier viceregal consorts Lady Dufferin [see Frederick Temple Blackwood*] and Princess Louise, Lady Aberdeen attended parliamentary debates, sitting between the speaker and the government benches. She followed the arguments with interest and reported back to her husband, providing him with a perspective on Canadian affairs. Sometimes described as a “governess general,” not in compliment, she joined him in addressing the leadership crisis that followed the death in December 1894 of their friend Prime Minister Sir John Sparrow David Thompson*. Her dislike of the obvious candidate, political veteran Sir Charles Tupper*, fears about the French–English and Catholic–Protestant conflict over the Manitoba school question [see Thomas Greenway*], and her preference for the Liberal leader, Wilfrid Laurier*, drove her to intervene more than many critics then and later have thought appropriate. She even used a colleague from the NCWC, Emily Ann McCausland Cummings [Shortt*], as an intermediary behind the scenes with Laurier. She was often censured for meddling in political affairs, but historian John T. Saywell, who claimed that Lady Aberdeen’s journal is the most important single documentary record of the young dominion in the mid 1890s, reckoned the countess a force for good. By the time the couple left Canada in 1898, she believed that the country, now under Laurier’s direction and with a well-established network of women’s councils (which owed much to her infusion of energy, cash, and social capital), could look forward to the more tolerant future she wished for the empire as a whole.

She returned to Britain to immerse herself in planning the London meetings of the ICW the following year. A prized reception by Queen Victoria at Windsor Castle during the conference signalled respectability. Lady Aberdeen’s editing of the seven volumes of reports presented at the gathering testified to the organization’s vitality; the creation of the International Woman Suffrage Alliance in 1904 revealed its limitations. That year American suffragist May Eliza Sewall became ICW president, but the Toronto meetings of 1909 returned Lady Aberdeen, who would hold office until 1920 and from 1922 to 1936. Her edited volume Our lady of the sunshine and her international visitors … (Toronto, 1910) celebrates Canada as the best expression of a liberal empire.

She also became involved once again in Liberal politics. Her cautious opposition to the South African War and to suffrage militancy was designed to maximize the party’s electoral appeal and promote the cause of Home Rule for Ireland. When she returned to that country in 1906, after Lord Aberdeen was reappointed lord lieutenant, it was to help promote an empire on the Canadian federal model. Friendships with political leaders such as Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman and sympathy for the “new liberalism,” with its embrace of expanded state welfare, failed to produce a suffrage dividend, however, and the new prime minister, Herbert Henry Asquith, in 1908 proved an anti-feminist. To Lady Aberdeen’s dismay, suffragists increasingly counted on the Labour Party, and the militant Women’s Social and Political Union gained ground.

She nevertheless endeavoured to improve conditions for imprisoned suffragettes in Ireland. Aberdeen’s second viceroyalty, from 1906 to 1915, saw her turn away from rural handicrafts to focus on public health and urban reform, notably under the auspices of the Women’s National Health Association of Ireland, which she led from its founding in 1907 and whose journal, Sláinte [Health] (Dublin), she edited. As in Canada, she faced resistance from extremists, this time aligned with either nationalist or unionist causes. She could run roughshod over opponents, but she was widely recognized as an unusual aristocratic benefactor, a proponent of what historian Frank Prochaska has called a “welfare monarchy.” World War I and the deteriorating political situation in Ireland encouraged Asquith to retire the Aberdeens, who were perceived as too strongly committed to the implementation of Home Rule. They spent much of 1915–17 in the United States, and occasionally Canada, fund-raising for Irish causes. Lady Aberdeen, now a marchioness, would retain her Irish commitments until her death, but the conservative nationalism of the Irish Free State proved hostile to women’s rights.

While the Rome meetings of the ICW in 1914 were highly successful, the war brought the organization to near collapse, and only Lady Aberdeen’s prestige and funds kept it afloat. The ICW endeavoured, with great difficulty, to remain above the conflict and to direct attention to post-war planning and reconciliation. But its claim to an uncertain middle ground aggravated pacifists and belligerents alike. By the time of the conference in Kristiania (Oslo), Norway, six years later, the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom was the leading feminist group opposing war. The Aberdeens’ hopes for international cooperation also lay with the emerging British Commonwealth and the League of Nations. A joint autobiography, “We twa”: reminiscences … (2v., London, 1925), suggests life’s twilight, but the marchioness kept working, notably on behalf of public health, child welfare, and peace, only retiring from the ICW presidency in 1936 when she believed she had a safe successor in Belgium’s liberal Marthe Boël.

By that time, even Canadians had become sceptical about her leadership. To the experienced Alberta politician Mary Irene Parlby [Marryat*], such women represented the past: commenting on the Washington meetings of the ICW in 1925, she remarked, “Lady Aberdeen, though evidently warmly regarded by many of the delegates and undoubtedly a woman of kindly, generous heart and sincere interest in her work, does not shine as a chairwoman.” From Parlby’s perspective, the future rested with unions and “the great agricultural organizations,” not aristocratic ladies. Her judgement reflected Lady Aberdeen’s marginality in the interwar women’s movement. The marchioness did, nonetheless, continue the good fight in the 1930s: assisting the Scottish branch of the League of Nations Union, organizing for the Peace Ballot in 1934, which attempted to mobilize British public opinion in favour of the League of Nations and disarmament, supporting republicans in the Spanish Civil War, and aiding Jewish refugees escaping Adolf Hitler’s Germany.

Her husband’s death in 1934 forced Lady Aberdeen to move to a mansion in the city of Aberdeen that she renamed Gordon House; she died there five years later, still planning assistance for Ireland and embattled Czechoslovakia. Her friend and fellow spiritualist Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King* mourned her, as did other Canadians. In old age she still returned the affection many in the country felt for her, insisting, “I am a Canadian. I have been a Canadian for a great many years. I shall always be a Canadian.” In the 21st century Lady Aberdeen survives in the collective memory as representative of a heritage of public duty that later feminist governors general, such as Adrienne Clarkson, have proudly embraced.

In addition to the works mentioned in the biography, Lady Aberdeen is the author of The musings of a Scottish granny (London, 1936) and, with her husband, Lord Aberdeen, Archie Gordon: an album of recollections of Ian Archibald Gordon (n.p., 1910); The women of the Bible (London, 1927); and More cracks with “we twa” (London, [1929]). She also edited Edward Marjoribanks, Lord Tweedmouth …: notes and recollections (London, 1909), and she wrote or edited reports of the quinquennial meetings of the International Council of Women for the years when she was president. A number of her addresses in Canada were published and are available through “Canadiana online”: www.canadiana.ca (consulted 26 Aug. 2019). Through Canada with a Kodak, originally published in Edinburgh in 1893, has been reprinted with an introduction by Marjory Harper (Toronto and Buffalo, N.Y., 1994). Lady Aberdeen is also the author of numerous short pamphlets and articles in journals and newspapers, many of which are identified in the author’s Liberal hearts and coronets: the lives and times of Ishbel Marjoribanks Gordon and John Campbell Gordon, the Aberdeens (Toronto, 2015), together with other sources for Lady Aberdeen’s life.

The main collection of Aberdeen papers is at Haddo House in Aberdeenshire, Scot. The manuscript of Lady Aberdeen’s Canadian journal is preserved at LAC as part of the John Campbell Hamilton Gordon, 1st Marquess of Aberdeen and Temair fonds (R5319-0-1). It was edited with an introduction by J. T. Saywell as The Canadian journal of Lady Aberdeen, 1893–1898 (Toronto, 1960). Excerpts related to British Columbia from 1890 onward appear in The journal of Lady Aberdeen: the Okanagan valley in the nineties, ed. R. M. Middleton (Victoria, 1986). The National Council of Women of Can. fonds (R7584-0-0), the International Council of Women fonds (R4657-0-7), and the Victorian Order of Nurses for Can. fonds (R2915-0-7) at LAC constitute the other major manuscript sources.

Lethbridge Herald (Lethbridge, Alta), 18 June 1925. Times (London), 19 April 1939. Amanda Andrews, “The great ornamentals: new vice-regal women and their imperial work, 1884–1914” (phd thesis, Univ. of Western Sydney, Sydney, Australia, 2004). Book of the Victorian Era Ball …, under the dir. of James Mavor (Toronto, 1898). C. S. Breathnach and J. B. Moynihan, “The frustration of Lady Aberdeen in her crusade against tuberculosis in Ireland,” Ulster Medical Journal (Belfast), 81 (2012): 37–47. Cynthia Cooper, Magnificent entertainments: fancy dress balls of Canada’s governors general, 1876–1898 (Fredericton and Hull, Que., 1997). Doris French, Ishbel and the empire: a biography of Lady Aberdeen (Toronto, 1988). J. M. Gibbon, The Victorian Order of Nurses for Canada: fiftieth anniversary, 1897–1947 ([Ottawa, 1947]). N. E. S. Griffiths, The splendid vision: centennial history of the National Council of Women of Canada, 1893–1993 (Ottawa, 1993). Marjory Harper, Emigration from north-east Scotland (2v., Aberdeen, Scot., 1988). Maureen Keane, Ishbel, Lady Aberdeen in Ireland (Newtownards, Northern Ire., 1999). Val McLeish, “Sunshine and sorrows: Canada, Ireland and Lady Aberdeen,” in Colonial lives across the British empire: imperial careering in the long nineteenth century, ed. David Lambert and Alan Lester (Cambridge, Eng., 2006), 257–84. ODNB (listed under her husband’s entry). L. M. Orr, “Ministering angels: the Victorian Order of Nurses and the Klondike goldrush,” B.C. Hist. News (Vancouver), 33, no.4 (fall 2000): 18–21. S. M. Penney, A century of caring, 1897–1997: the history of the Victorian Order of Nurses for Canada (Ottawa, 1996). Marjorie Pentland, A bonnie fechter: the life of Ishbel Marjoribanks, Marchioness of Aberdeen & Temair … 1857 to 1939 (London, 1952). Thomas Wayling, “Granny emeritus: Canadian forever,” Canadian Home Journal (Toronto), 34 (1937–38), no.4: 26–7, 37. Women in a changing world: the dynamic story of the International Council of Women since 1888 (London, 1966).

Cite This Article

Veronica Strong-Boag, “MARJORIBANKS, ISHBEL MARIA (Hamilton-Gordon, Marchioness of ABERDEEN and TEMAIR),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 20, 2024, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/marjoribanks_ishbel_maria_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/marjoribanks_ishbel_maria_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Veronica Strong-Boag |

| Title of Article: | MARJORIBANKS, ISHBEL MARIA (Hamilton-Gordon, Marchioness of ABERDEEN and TEMAIR) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2019 |

| Year of revision: | 2019 |

| Access Date: | December 20, 2024 |