Source: Link

ORCHARD, ANNIE (Rutherford), temperance advocate and social activist; b. 14 Sept. 1856 in Galt (Cambridge), Upper Canada, daughter of John Orchard and Lucinda Montgomery; m. 6 Jan. 1886 Peter Rutherford (1858–1938) in Brantford, Ont., and they had a daughter, who predeceased her; d. 29 Feb. 1940 in Toronto.

Annie Orchard moved from Galt to nearby Brantford as a young child. Her father, a successful tailor, provided his daughter with a post-secondary education, which was consistent with the family’s status and religion but rare for a woman to receive at that time. After attending public school in Galt, Annie studied at the Brantford Grammar School and then at Hamilton’s Wesleyan Female College. Her Wesleyan Methodist faith was strengthened by her time at the college, and she would remain active in her church, which became the United Church of Canada after the 1925 union with Presbyterians and Congregationalists [see Samuel Dwight Chown; Clarence Dunlop Mackinnon]. In 1886 Annie married Peter Rutherford, a bookseller from Owen Sound who was well known in the area; his father, John, was mayor of the nearby town of Flesherton. For the rest of her life she would commonly be referred to as Annie O. Rutherford. Unlike many of her contemporaries, who often decreased or abandoned their charitable activities after marriage, she became even more involved in social reform.

Annie had been introduced to the cause of temperance through her membership in the local Band of Hope, an organization for young people run by the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU). She was committed to the temperance movement, primarily through her leadership in the WCTU at both the national and provincial levels. Around age 25 she began her work with the Ontario WCTU under its founding president, Letitia Youmans [Creighton*]. Annie was given her first significant role in October 1881 when she was elected recording secretary, a post she would hold for the next 12 years.

During her time as recording secretary Annie was also superintendent of scientific temperance instruction. Under her leadership the department reached its peak and performed some of the Ontario WCTU’s most impressive work. Assisted by Adeline Chisholm [Davis*], Youmans’s successor as president, and supported by the Woman’s Journal (Ottawa), published first by Chisholm and later by Mary McKay Scott, Annie oversaw the Ontario WCTU’s campaign to have temperance education added to the public-school curriculum. She delivered speeches and participated in deputations to government officials: for example, she organized and presented petitions to Adam Crooks* and George William Ross*, successive ministers of education in the Liberal government of Oliver Mowat*. Her efforts helped the WCTU earn one of its greatest victories: a voluntary course on scientific temperance, with a WCTU-approved textbook, was introduced into public schools in 1885 and made mandatory in 1893. Following this triumph Rutherford became vice-president of the Ontario WCTU. She would go on to serve as president of the Dominion WCTU from 1895 to 1905. Annie undertook speaking tours to promote the cause, travelling across the country. Under her leadership the WCTU maintained its focus on education and made important gains in membership through the growth of the young women’s branch. She also led the campaign for the legislated prohibition of alcohol. In 1905 she declined to stand for re-election because of disability resulting from an accident. Sarah Alice Wright [Rowell*] was chosen in her stead.

Rutherford’s activism was not limited to the WCTU; she dedicated herself to a number of other causes that related to her religious faith or her commitment to women’s issues. She served terms as a vice-president and on the executive committee of the Ontario branch of the Temperance Alliance in the 1890s and the early 1900s, and was vice-president of Ontario’s Lord’s Day Alliance [see John George Shearer*]. During her career Annie fulfilled various roles in the Laymen’s Association and the Woman’s Missionary Society (WMS) of her church. In 1898, in her role as WCTU president, she proposed cooperation between the WCTU and the WMS to oppose the rumoured enslavement of Chinese girls in Canada.

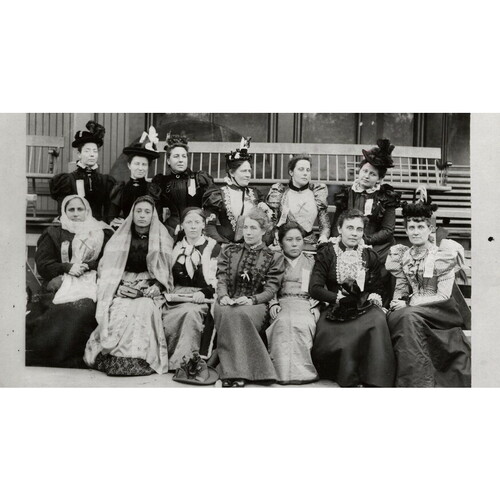

Rutherford was a delegate at the 1895 annual meeting in Toronto of the National Council of Women of Canada, headed by Lady Aberdeen [Marjoribanks], the wife of Governor General Lord Aberdeen [Hamilton-Gordon]. Like many WCTU members, whose organization adopted a pro-suffrage position in 1895, Rutherford believed that Canadian women should have the right to vote. In February 1896 she played the role of speaker of the house in a mock parliament performance in Toronto by well-known suffragists, including Dr Emily Howard Stowe [Jennings*], her daughter Ann Augusta Stowe* Gullen, and teacher Edith Sarah Lelean. Rutherford was also part of informal international suffrage networks that included women such as American Susan Brownell Anthony.

In the early 1900s Rutherford was deeply involved in ensuring the success of a Toronto medical institution that was known first as the Woman’s Medical College (1883–95) and then as the Ontario Medical College for Women (1895–1906). It functioned as a dispensary for several years and was reopened in 1911 (and formally incorporated two years later) as the Women’s College Hospital and Dispensary. This important facility, called the Women’s College Hospital since 1924 and still in operation in the early 21st century, was dedicated to meeting the needs of female patients and employed female doctors at a time when few opportunities were available to them. Authors Martin Kendrick and Krista Slade observe that many influential Canadians, such as Dr Helen MacMurchy*, played a part in the facility’s early history, and that Rutherford was “arguably the most prominent and persuasive of this group.” In 1936, reminiscing to the Toronto Globe about setting up the hospital, Annie recalled: “That was a battle and work of faith. I hardly think the women physicians knew what we went through.” She was president of the board of directors from 1909 to 1923, and she also led the training-school committee.

Annie O. Rutherford’s activism was exceptional at a time when it was difficult for women to play a prominent role in Canadian public life. Her success in lobbying Ontario politicians to bring scientific temperance instruction into the public-school curriculum demonstrates that women could and did participate effectively in politics even when they were denied the vote. Rutherford engaged women in conversations about social reform and provided them with admirable leadership until her death in 1940.

AO, F 885 (Canadian Woman’s Christian Temperance Union fonds); RG 80-8-0-1953, no.002874. Globe, 8 Jan. 1936. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1912). History of woman suffrage, ed. E. C. Stanton et al. (6v., New York and Rochester, N.Y., 1881–1922), 4 (1883–1900, ed. S. B. Anthony and Ida Husted Harper, 1902). Martin Kendrick and Krista Slade, Spirit of life: the story of Women’s College Hospital (Toronto, 1993). S. G. E[lwood] McKee, Jubilee history of the Ontario Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, 1877–1927 (Whitby, Ont., [1927?]). The Prohibition leaders of America, ed. B. F. Austin (St Thomas, Ont., 1895). M. F. Whiteley, Canadian Methodist women, 1766–1925: Marys, Marthas, mothers in Israel (Waterloo, Ont., 2005).

Cite This Article

Patricia Kmiec, “ORCHARD, ANNIE (Rutherford),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 31, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/orchard_annie_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/orchard_annie_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Patricia Kmiec |

| Title of Article: | ORCHARD, ANNIE (Rutherford) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2024 |

| Year of revision: | 2024 |

| Access Date: | December 31, 2025 |