Source: Link

JENNINGS, EMILY HOWARD (Stowe), schoolteacher and principal, physician, and suffragist; b. 1 May 1831 in Norwich Township, Upper Canada, eldest child of Hannah Lossing Howard and Solomon Jennings, farmers; m. 22 Nov. 1856 John Stowe in Norwichville (Norwich), and they had one daughter, Ann Augusta*, and two sons; d. 30 April 1903 in Toronto.

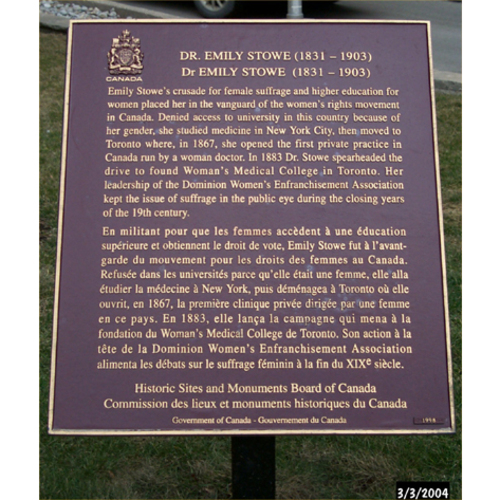

The first female public-school principal in Ontario, the first Canadian woman openly to practise medicine, and a founding member of the Canadian Women’s Suffrage Association, Emily Howard Jennings ranks as a true pioneer. Her forebears were early settlers in the New England and New Netherlands colonies who had come to Upper Canada at the beginning of the 19th century. Peter Lossing*, her maternal great-grandfather, had bought 15,000 acres in Norwich Township in 1810 and moved there from New York to live. The Jenningses, originally of Vermont, were farmers who also settled in Norwich.

Established and prosperous members of the Society of Friends (Quakers), the Lossing and Jennings families commanded respect both north and south of the border. Economic, political, and spiritual leaders in the Norwich community, they shaped their public lives according to their principles of equality and pacifism and were influenced by the American agrarian ethos and radical republicanism. Both families developed strong links with the Upper Canadian reformers. A commitment to equality was evident in their private lives as well as their public ones. The Lossing women were strong and equal participants with men at Friends’ meetings. They were also educated. Ties to the United States allowed them to obtain a formal education at Quaker seminaries there. Emily’s mother was sent back to her native Cranston, R.I., to study at the seminary in nearby Providence. She in turn ensured that her daughters received as rigorous an education as she had had. Dissatisfied with the three schools in Norwich Township, she taught the girls at home. In addition to a general knowledge and a love of learning, she apparently passed on her skills in herbal healing.

The composition of the Howard/Jennings family contributed to the girls’ autonomy. The only son died in infancy, and the six daughters assumed much of the outdoors and farming work that would otherwise have been consigned to him. They also achieved some economic independence. At age 15 Emily accepted employment as a schoolteacher in the neighbouring town of Summerville, and she taught for seven years.

Emily’s public struggle to achieve equality for women began in 1852, when she applied for admission to Victoria College, Cobourg. Refused on the grounds that she was female, she applied to the Normal School for Upper Canada, which Egerton Ryerson* had recently founded in Toronto. She entered in November 1853 and was graduated with first-class honours in 1854. Hired as principal of a Brantford public school, she taught there until her marriage in 1856.

It is not known how Emily had met John Stowe, a native of Yorkshire who had immigrated to Canada at the age of 13. His family had settled near Brantford in Mount Pleasant, where his father founded the Stowe Brothers Carriage Shop. John later assumed the business, and after marrying, he and Emily lived in the village. He shared his wife’s political ideals, although he was a Methodist and later became a lay preacher. The Stowes did not marry at a Friends’ meeting. Emily apparently converted to Methodism, but formal religion did not play a strong role in her subsequent life. At the end of her career she would write that she had “out grown all religious creeds” and that she was “a Truth Seeker . . . a Mental Scientist Looking upon Jesus Christ as our great exemplar & at the same time regarding him as pre-eminently a socialist – I am bold to say, I am a Scientific Socialist & would like to see the unity of humanity & nations fully recognized – until which the Kingdom of Heaven is afar off.”

Shortly after the birth of their third child, in 1863, John contracted tuberculosis. The impact of his illness upon the family economy is unclear. Ostensibly faced with the prospect of supporting her family, Emily accepted a teaching position at the local grammar school. Simultaneously she began to investigate possibilities for medical training. Biographers have suggested that John’s illness compelled Emily to provide for the family. It seems unlikely, however, that economic considerations motivated her to study medicine. Physicians were not well paid in mid-19th-century Upper Canada, and there were no provisions for women to join the profession. If Emily was acting out of financial necessity, it is odd that she abandoned the teaching career for which she had qualified in favour of a long course of study and a protracted battle over professional credentials. Moreover her relatives were prosperous and well established, and she enjoyed their support during her husband’s illness. Her sister Cornelia Lossing stepped in to care for the children while Emily pursued her medical training. That two other sisters, Hannah Augusta and Ella, also completed studies in the field suggests a pervasive family interest in it.

The opportunities to study medicine were extremely limited in Canada. Emily apparently applied to the Toronto School of Medicine, affiliated with the University of Toronto, although the exact date of her application is uncertain. The university, however, did not admit women. By 1865 she had resolved to train in the United States. She enrolled at the New York Medical College for Women, a homoeopathic institution in New York City founded by Clemence Sophia Lozier. The precise date at which she entered the college is unclear, but it was likely 1865. She received her degree in 1867.

The inhospitable climate for women’s education in Canada was probably only one of the factors that compelled Stowe to pursue her studies in New York. The Lossings and the Howards had maintained close ties with their American friends and relatives, and they had often sent their children, specially daughters, south to study. It is also likely that Emily sought homoeopathic training. Her mother had long taken part in herbal healing, and Joseph J. Lancaster, a homoeopathic physician who practised in Norwich until 1848, was a close friend of the Jennings family. Emily displayed her own affinity for homoeopathy. She was apprenticed to Lancaster (possibly as early as the 1840s) and she chose to attend a homoeopathic medical college. In 1886 she would join the staff of the Toronto Homoeopathic Hospital and Richmond Street Dispensary. The Stowes also betrayed more subtle homoeopathic leanings. Upon their marriage she and John had built themselves an octagonal house, of the sort that Lancaster had also built and that was much prescribed by eclectic and homoeopathic practitioners of the 1850s. If Emily wished to practise homoeopathic medicine and study it formally, then she had no choice but to go south, for there were no training programs in Canada.

Upon graduation Dr Emily Stowe immediately set up practice on Richmond Street, Toronto. However, she did not procure a professional licence. Medical practice and licensing changed considerably during the 1860s as orthodox allopathic physicians attempted to consolidate their authority and erode the position of homoeopaths and eclectics through new requirements for registration. Legislation for the province in 1865 and 1869 changed the structure and composition of the medical licensing boards in ways that made it increasingly difficult for homoeopaths and eclectics to qualify. Stowe apparently could not meet the requirements. Her situation was complicated by the fact that no Canadian medical school would accept women. Stowe later recalled that she had applied in 1869 for admission to classes in chemistry and physiology at the University of Toronto but the senate had denied her a place. She remembered also that when John McCaul*, president of University College, conveyed the decision to her, she had “replied expressing my regret & at the same time remarking that these university doors will open some day to women at which he with some vehemence answered Never in my day Madam.”

Emily Stowe therefore practised medicine without a licence. In 1870, after the president of the Toronto School of Medicine, Dr William Thomas Aikins*, opened it specially to her and Jenny Kidd Trout [Gowanlock*], she attended classes for a session. There is, however, no record of her having sat the professional examinations conducted by the board of examiners of the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario. It is not known whether she was prevented from taking them, took them and failed, or refused to take them. According to some accounts the male professors’ and students’ behaviour in class had so angered her that she would not sit the exams. In conversation with Trout, it is said, she also claimed that she feared the licensing body would discriminate against a homoeopath. There is no evidence that Stowe was ever prosecuted for practising without a licence; however, in 1879 she was charged with having performed an abortion. After a lengthy trial, in which her qualifications were tested and members of Toronto’s medical establishment called to bear witness to her character, skill, and professional conduct, she was acquitted.

On 16 July 1880 the College of Physicians and Surgeons suddenly and inexplicably granted Stowe a medical licence. Whether it did so because of the skill she had demonstrated during her trial, or because expert witnesses justified her right to practise medicine, remains unclear. Dr Aikins was among those who testified to her credentials and well-established practice. The wording in the Ontario medical register (Toronto), “in practice prior to 1st January 1850,” suggests that the college had accepted Dr Aikins’s testimony and chosen to use her early apprenticeship with Lancaster to legitimize both her standing and the profession’s; a section of the Ontario Medical Act of 1869 admitted those who had been practising before 1850.

Stowe wrote no articles or other tracts on medicine. She advertised herself as a specialist in diseases of women and children, and the events leading to her trial as an abortionist indicate that she catered specially to these populations. She was a strong proponent of women’s interests. Whilst a student in New York, she attended numerous women in hospital and home and staunchly defended the need for female physicians to treat female patients. Though trained by an eclectic and initiated into the therapeutic use of electricity, she apparently opposed its application, especially as it was practised by Jenny Kidd Trout, now a qualified doctor and her rival. Stowe supported the sanitary ideal, which located the causes of disease in filthy and corrupt urban conditions, and she promoted public health reform.

A deep commitment to egalitarianism informed Stowe’s personal relationships. Equal partner with her husband, she pursued her own medical career and then supported him while he retrained. By 1873 John Stowe had regained his health, obtained employment as a bookkeeper, and joined his wife. He spent the next two years training as a dentist and sat the qualifying exams in 1875. The Stowes then practised side by side at 111 Church Street.

Emily Stowe repeatedly translated her private egalitarianism into her public life. Her struggles for a career formed part of a broad commitment to women’s education. She worked valiantly and untiringly in the general cause of medical studies for women; in May 1869 she delivered a lecture on female physicians to the Toronto Mechanics’ Institute in which she argued that “woman, as mother of the race, has a greater magnitude of responsibility than she realizes.” Stowe supported her sisters’ decision to pursue medical studies, and she had played a similar role in the career development of Jenny Kidd Trout. In 1879, when Augusta Stowe decided to follow her mother into medicine, Emily unrelentingly pushed to open the doors of the University of Toronto. In 1883 Augusta would become the first woman to receive a Canadian medical degree.

Although Augusta took her classes with men at the Toronto School of Medicine, she was an exceptional case and the women who attempted to follow her lead found the university doors once again closed. Emily Stowe participated in the ensuing debate over women’s medical education and played a role in the founding of the Woman’s Medical College in Toronto in 1883. Though she was a staunch advocate of professional education for women – in 1890 she would similarly champion Clara Brett Martin*’s efforts to qualify in law – she disagreed on matters of scope and policy with her colleagues who established the Women’s Medical College at Kingston in 1883. The controversy, rooted in a personal rivalry between Stowe and Trout and in a disagreement over the importance of equity, also took on a nationalistic dimension. Led by Elizabeth Smith* and Trout, the Kingston group believed it necessary to found a Canadian school especially for women, and to do so at any educational cost. Stowe, committed to principles of equality, thought it more critical for women to make certain that they had the same qualifications as men. Unlike some of the women with whom she worked, she did not believe in a special woman’s nature. She dismissed the notion that feelings were women’s particular domain and she regularly defended their ability to study mathematics and science alongside men. She downplayed nationalism. The value of a Canadian degree, she wrote to Smith, “is more imaginary than real.”

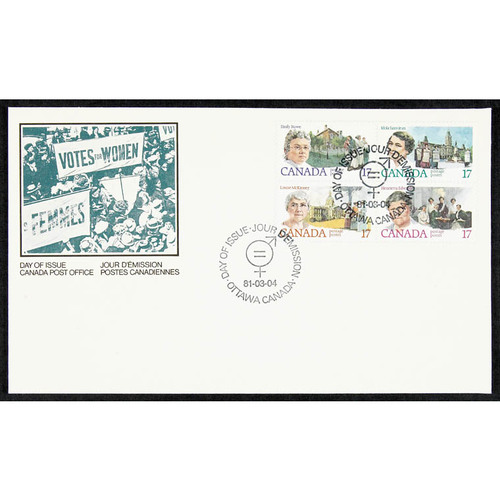

Under the tutelage of Clemence Sophia Lozier, who was noted for her dedication to woman suffrage and black emancipation, Stowe had become a strong proponent of equity, and her political work would be infused by a commitment to ensuring that women received the same services as men. When she returned to Ontario in 1867, Canadian women had not yet begun to organize, but during the 1870s, as they embraced the causes of education, enfranchisement, and temperance that marked woman’s reform in this country, Stowe led and gave shape to their efforts. In 1877, after travelling to Cleveland, Ohio, to attend a meeting of the American Society for the Advancement of Women, she founded the Toronto Women’s Literary Club. This group, which included Sarah Anne Curzon [Vincent*], devoted itself to promoting women’s intellectual development and higher education. Likely inspired by the Philadelphia Convention of 1876, a gathering of women’s rights activists, and the suffragist efforts of Susan Brownell Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, whom Stowe had known since her days as a medical student, the club attempted to improve women’s access to the political process. It construed higher education broadly and worked to promote the physical welfare of women by embracing sanitary and public-health reforms, especially as they pertained to work. Club members decried the evils of the sweatshop system and lobbied for the improvement of conditions for clerks and store and factory labourers. They argued as well that women’s opportunities for employment and their circumstances at work suffered because they could not vote. Gradually the club more openly promoted women’s rights, especially the right to vote. In 1883 it reconstituted itself as the Canadian Women’s Suffrage Association, with Emily Stowe as one of the vice-presidents.

Stowe is best known for her contributions to the enfranchisement of women. She campaigned to win women the same property and voting rights as men, and she helped to obtain passage by the province in 1884 of the Married Women’s Property Act, which placed spouses on an equal footing with regard to property they owned separately. The suffrage association lost energy after 1885, in Stowe’s view because “we admitted the opposite sex as members and the effect was demoralizing. That old idea of female dependence crept in and the ladies began to rely on the gentlemen rather than upon their own efforts.” Stowe breathed new life into the association by arranging for the American suffragist Dr Anna Howard Shaw to speak in Canada. The occasion of that address, on 31 Jan. 1889, led to the formation of a national organization – the Dominion Women’s Enfranchisement Association. Stowe became the first president and she held the position until her death. In this capacity she led a deputation to the Ontario legislature demanding the vote, and called a convention of women’s suffrage clubs from across Canada, which was held in Toronto in 1890. After her husband’s death in 1891, she turned her attention increasingly to the political causes that had come to dominate her agenda. In February 1896 she played a lead part in the mock parliament at Toronto, which had been organized to parody and publicize the inequalities suffered by women under the Canadian governmental and judicial systems.

Stowe’s arguments in favour of the vote for women illustrate the dual commitments to equity and maternalism that guided the late-19th-century women’s movement in Canada. Though she was dedicated to ensuring that women could participate equally with men in the public world and though she rejected any suggestion that women had a special nature, she affirmed the sanctity and value of women’s work within the home. She insisted repeatedly that their role as mothers gives women a measure of responsibility for the human race which even they do not fully appreciate. Hence she championed women’s education and enfranchisement not only on grounds of equity but because she believed that girls needed to be educated for their duties in the home and that factory work left them unprepared to assume their roles as wives and mothers. Convinced that “homemaking of all occupations that fall to women’s lot, is the most important and far reaching in its effects on humanity,” she made the case for paid housework. As much a social reformer as a political one, she repeatedly linked the causes of suffrage, education, and work on grounds that reform could not be achieved “until woman has her place in the body social and economic.” When talking about “woman’s sphere” at Toronto and Brantford she deprecated the position to which women had been reduced and called for women’s education to redress the inequity.

Stowe’s advocacy of maternal rights, women’s property rights, and enfranchisement was typical of the late-19th-century women’s movement in Canada; so were the methods she used to make her case. Unlike their American sisters, Canadian suffragists rarely employed civil disobedience and public outcry. Stowe typically and characteristically publicized her cause through petitions, lobbying, addresses, letters to newspapers, and a series of editorials signed xyz. She resorted as well to religious rhetoric to rally Canadians to her causes. Stowe also joined forces with and contributed to the work of other major Canadian women’s associations, among them the National Council of Women of Canada, founded in 1893, and the temperance movement.

In May 1893, at the quinquennial convention of the International Council of Women, held in Chicago, Emily Stowe fell from the platform and broke her hip. The injury limited her participation in the work of the National Council of Women and also led to her retirement from medical practice. She spent the rest of her life with her son Frank Jennings Stowe, a dentist, and her daughter, who lived side by side at 461 and 463 Spadina Avenue. She died in 1903, and after the funeral her family escorted the body to Buffalo for cremation.

Despite her stature as one of its leaders, Stowe differed to some extent from other contributors to the Canadian women’s cause. Her decision to practise medicine without a licence betrayed a disregard for the niceties of the law that was uncharacteristic of her fellow reformers. This disregard also manifested itself in her abortion trial and in her portrayal of the position of the provincial attorney general during the mock parliament. Her attitude, and the firmness with which Stowe pursued her goal, did not always inspire the admiration of other Canadian woman reformers. In a letter to her sister, Elizabeth Smith described “seeing Mrs. Dr. Stowe and Mr. Stowe in Toronto at a wedding . . . Mrs. S. seemed to be the biggest man of the two.” Perhaps Stowe was thinking, in part, of these differences when she wrote in 1896, “My career has been one of much struggle characterized by the usual persecution which attends everyone who pioneers a new movement or steps out of line with established custom.”

Primary documents relevant to the life of Emily Howard Jennings Stowe are found in several archives. The largest but least systematically organized of these collections consists of the Augusta Stowe Gullen scrapbooks, which are divided between Wilfrid Laurier Univ. Arch. (Waterloo, Ont.) and the Augusta Stowe Gullen coll. in Victoria Univ. Library (Toronto). Some letters from Emily Stowe are included among the Elizabeth Smith Shortt papers in the Doris Lewis Rare Book Room at the Univ. of Waterloo Library, and other pertinent materials are found in collections at the AO, the QUA, and Trinity College Arch., Toronto.

College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario (Toronto), Minutes of the medical college council meeting, 16 July 1880. MTRL, Peter Lossing papers. NA, MG 29, D61: 7762. Evening News (Toronto), 9 Feb. 1889, 13 June 1890. Evening Star (Toronto), 20 Feb. 1893. Globe, 13 June 1883, 9 Feb. 1889, 14 June 1890, 19 Feb. 1896, 1 May 1903. News (Toronto), 2 May 1903. Toronto Daily Star, 30 April 1903. C. L. Bacchi, Liberation deferred? The ideas of the English-Canadian suffragists, 1877–1918 (Toronto, 1983). C. [B.] Backhouse, Petticoats and prejudice: women and law in nineteenth-century Canada ([Toronto], 1991). Mary Beacock Fryer, Emily Stowe, doctor and suffragist (Toronto and Oxford, 1990). Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898). C. L. Cleverdon, The woman suffrage movement in Canada, intro. Ramsay Cook (2nd ed., Toronto, 1974). Jacalyn Duffin, “The death of Sarah Lovell and the constrained feminism of Emily Stowe,” Canadian Medical Assoc., Journal (Toronto), 146 (January–June 1992): 881–88. C. M. Godfrey, Medicine for Ontario: a history (Belleville, Ont., 1979). History of homeopathy and its institutions in America . . . , ed. W. H. King (4v., New York, 1905), 3: 147. E. M. Luke, “Woman suffrage in Canada,” Canadian Magazine, 5 (May–October 1895): 328–36. Wendy Mitchinson, The nature of their bodies: women and their doctors in Victorian Canada (Toronto, 1991). Alison Prentice et al., Canadian women: a history (Toronto, 1988). H. M. Ridley, A synopsis of woman suffrage in Canada (Toronto, n.d.). Augusta Stowe Gullen, A brief history of the Ontario Medical College for Women ([Toronto?], 1906). V. [J.] Strong-Boag, “Canada’s women doctors: feminism constrained,” A not unreasonable claim (L. Kealey), 109–29; The parliament of women: the National Council of Women of Canada, 1893–1929 (Ottawa, 1976). J. E. Thompson, “The influence of Dr. Emily Howard Stowe on the woman suffrage movement in Canada,” OH, 54 (1962): 253–66.

Cite This Article

Gina Feldberg, “JENNINGS, EMILY HOWARD (Stowe),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 31, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/jennings_emily_howard_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/jennings_emily_howard_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | Gina Feldberg |

| Title of Article: | JENNINGS, EMILY HOWARD (Stowe) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1994 |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | December 31, 2025 |