Source: Link

CREIGHTON, ELIZA JANE (Harvie), homemaker and social reformer; b. 11 March 1840 near Peterborough, Upper Canada, daughter of Kennedy Creighton and Laura Hart; m. 1 May 1861 John Harvie* in Aurora, Upper Canada, and they had a son and three daughters; d. 22 June 1929 in Toronto.

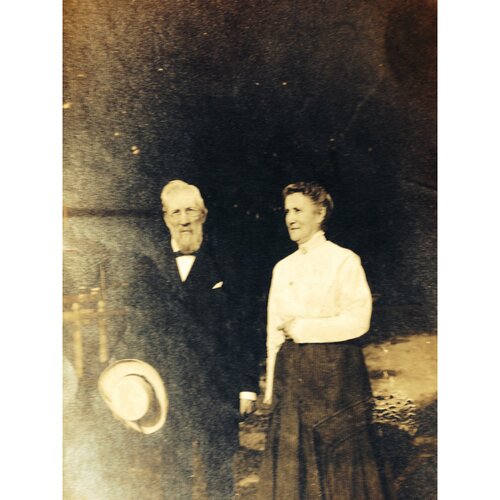

Lizzie J. Creighton, as she was known publicly and to her family, was the second of the five surviving children of an Irish-born Methodist minister and his wife, a native of Pennsylvania. She had a childhood of change: by the time she was ready for formal schooling, in Bytown (Ottawa), she had been in ten parsonages. She finished her education at the Wesleyan Ladies’ College in Dundas. When she was at home, she and her brother John R. ran their father’s Sunday school, a vocation she would follow throughout her life. A slight woman, perhaps five and a half feet in height, she had a strong face (to judge from her pictures) and was precise in her habits.

In 1860, when her father was chair of the church’s Barrie district, she attracted the attention of John Harvie, the senior conductor on the Northern Railway. Family tradition says she picked him out as he was dancing in a hotel in Aurora. Following their marriage by her father, they settled in Toronto, near the Northern’s yards. John was a staunch Presbyterian, and Lizzie converted. In 1865 they were living in Collingwood, where John was the station agent, but the next year they were back in Toronto. On John’s appointment as train and traffic manager of the Northern, the family moved into a house supplied by the railway. Lizzie must have been busy. By the time she was 29, she had four children, a large house, and her work in West Presbyterian Church. In July 1874 tragedy struck when her daughter Mary died. Her reaction was a wonderful example of her approach to life: health care for children must be improved. That winter she participated in meetings with Elizabeth Jennet McMaster [Wyllie*], Lady Macdonald [Bernard*], and others which led to the opening of the Hospital for Sick Children in March 1875.

Other philanthropic work soon followed. In 1876 a group of laywomen formed the Woman’s Foreign Missionary Society of the Presbyterian Church in Canada (Western Division). Harvie became its foreign secretary, a post she would hold until 1896, with one interruption due to ill health in 1888–90. The society focused on missions abroad [see Agnes Maria Turnbull*] and native schools and missions in the Canadian west. Not only did it raise money for these operations, in the case of the western missions it helped collect clothing and blankets. In addition to handling correspondence, Harvie toured Ontario, setting up auxiliaries and mission bands, visiting branches, and making speeches. The society’s Monthly Letter Leaflet gives many glimpses of her activities. By 1876 she had also joined the board of the Women’s Christian Association, which ran a boarding house for single, young working women, principally from outside Toronto. Volunteer members also visited females in the city jail. Harvie sat on the jail committee (and on the hospital and house of industry committees) and she soon realized that a discharged inmate had no support if she wanted to change upon re-entering society. In early 1878 she persuaded the WCA to open the Haven, a lodging house for former prisoners. To fund this operation (named the Toronto Prison Gate Mission), she employed the technique that had worked for the children’s hospital: start the project and have the city’s philanthropically inclined provide the necessary resources. By 1878 she had become, as well, corresponding secretary of the Toronto branch of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, which had been brought to Ontario by Letitia Youmans [Creighton*], possibly a distant cousin. Harvie assisted in the formation of the provincial WCTU. She must have found it easy to join the temperance movement: her father and husband had both lived in communities degraded by alcohol and were proponents of prohibition.

Harvie’s volunteer work was interspersed with domestic crises. In 1878 the Northern made her husband stationmaster of Toronto’s new Union Station, a move he resented. It meant the loss of the company residence, but through his dabbling in real estate another house was found. His poor health forced a long leave of absence and a recuperative trip to Scotland – Harvie remained in Toronto, anxious about the future – and he finally retired from the Northern in 1881. Her other concern was their rebellious elder daughter, Jean Ferguson. Harvie managed to find occupation for her on the WCA’s board and the ladies’ committee of the Hospital for Sick Children, of which Harvie was a president. Jean married in 1885. The same year John became permanent secretary of the Upper Canada Bible Society and Lizzie’s father had a violent stroke. (The Creightons subsequently moved in with the Harvies.)

From her work for the hospital, Harvie knew Emily Howard Stowe [Jennings*] and Jenny Kidd Trout [Gowanlock], two doctors who also sat on the WCA’s board. Originally forced to go to the United States for training, they were determined to provide medical education for women in Toronto. In 1886, with Harvie as treasurer, they opened Woman’s Medical College. It was likely through Harvie that Stowe’s daughter, Ann Augusta*, became acting physician to the Prison Gate Mission. The Haven created some tension within the WCA. Most of its directors preferred the more genteel parts of the operation, such as Christian instruction, but as its corresponding secretary and its president from 1887, Harvie was devoted to its practical success. Under her direction the Haven was opened to “every lost woman” (not just former inmates), the city was divided into districts for systematic fund-raising, and a new building was erected. Her continuing commitment to working women was illustrated in May 1887 when she became the founding president of the Toronto Young Women’s Christian Guild (the highly successful predecessor to the city’s Young Women’s Christian Association). Its relations with the WCA were soured at one point by a legacy from William Gooderham*, which was directed to an organization that could have been either the guild or the association. The case went to court, but a settlement was arranged before judgement.

In 1894, a year after Harvie had attended the Woman’s Congress staged in Chicago by the National American Woman Suffrage Association, the WFMS decided to send two executive members to the west to get information regarding its work there, especially to see if its collection of clothing and blankets was justified. On 1 Aug. 1894 Harvie, secretary of supplies Cecilia Mary Jeffrey, and their husbands set out, following an itinerary prepared by the Reverend Andrew Browning Baird of Manitoba College. Harvie was back on 18 September, having covered some 4,300 miles by rail and steamboat and over 600 miles of trails. The ladies had visited every Presbyterian mission and reserve school, as well as all of the society’s auxiliaries in Manitoba and the northwest. Their report reflects contemporary views of aid and assimilation. The schools were well run, the mission personnel and teachers were dedicated, and the natives who had converted and lived nearby were better off than the non-Christians. Harvie and Jeffrey found that more money was needed and that clothing and blankets were vitally important.

Major changes occurred in Harvie’s life in the 1890s. After a protracted battle, the all-male trustees of the Hospital for Sick Children, led by John Ross Robertson*, wrested total financial control from the ladies’ committee in 1891. The real estate investments of her husband were hit by recession, her daughter Laura left home on her marriage to her cousin the Reverend William Black Creighton (for whom Harvie would find a job at the Christian Guardian), her unambitious son finally married, and her father died in February 1892 and her mother in December 1895. The Harvies then moved to a boarding house. Lizzie’s new-found liberty, including her resignation from her positions in the WFMS and the Prison Gate Mission, allowed her in April 1896 to accept a paying job in social work, as the first assistant of John Joseph Kelso*, Ontario’s newly appointed superintendent of neglected and dependent children. Hired to visit and report on foster children across the province, she was well suited for this daunting task, which she entered upon with all the enthusiasm she had displayed at the WFMS and the WCA. In 1905 alone she made 830 visits. She would retire only in 1911 at the age of 71, two years after John’s retirement from the Bible society.

After living in a series of boarding houses, the Harvies ended their rootless existence by moving into a flat in the residence of their daughter Jean. Following John’s demise in a sanitarium in 1917, Harvie stayed with Jean until the latter’s death in 1923. She spent her last years in Laura’s home. To the end she remained willing to correct and improve family and visitors.

Lizzie J. Harvie’s contributions to the Women’s Christian Assoc., the Prison Gate Mission and Haven, the Toronto Young Women’s Christian Guild, and the Hospital for Sick Children are noted in the annual reports for these organizations reproduced on microfiche in CIHM. Her reports as a visitor in the neglected children’s branch of the Department of the Provincial Secretary are found in Ont., Legislature, Sessional papers.

AO, RG 80-8-0-1119, no.5256. Globe, 24 June 1929. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1912). Philip Creighton, “John Harvie,” York Pioneer (Toronto), 81 (1986): 1–15. Directory, Toronto, 1880–85. Presbyterian Church in Canada, Woman’s Foreign Missionary Soc. (Western Div.), Monthly Letter Leaflet (Toronto), 1884–96 (available on microfiche in CIHM).

Cite This Article

Philip Creighton, “CREIGHTON, ELIZA JANE (Harvie),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 27, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/creighton_eliza_jane_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/creighton_eliza_jane_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | Philip Creighton |

| Title of Article: | CREIGHTON, ELIZA JANE (Harvie) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | April 27, 2025 |