Source: Link

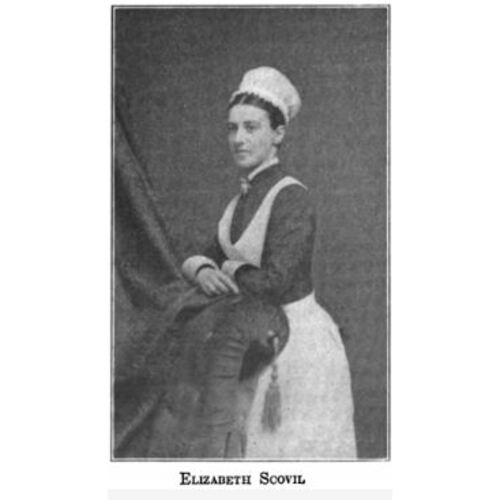

SCOVIL, ELISABETH ROBINSON (although she often appeared in print as Elizabeth, she signed Elisabeth), teacher, nurse, and author; b. 30 April 1849 in Saint John, daughter of Samuel James Scovil, a lawyer, and Mary Eliza Robinson; great-grandniece of John Robinson*; d. unmarried 20 Nov. 1934 in Bishop’s Stortford, England, and was buried there.

Elisabeth Robinson Scovil was descended on her father’s side from a long line of Church of England clergymen, including one of the first Anglican priests to settle in New Brunswick, a loyalist who arrived in 1788. Her mother came from a prominent military and political family, also loyalists. Education for Scovil was privately arranged and lasted until she was 16. Always an avid reader, she became well versed in Scripture and was also proficient on the pianoforte. When she was 19, her life of privilege was disrupted by the bankruptcy, attempted flight, and temporary jailing of her father. The disgraced family moved to her mother’s former home in Douglas, near Fredericton, and Elisabeth taught for a time in York County. The stigma of her father’s troubles was such that he was never again able to find employment. Rescue came in 1879 in the form of a bequest of a Scovil family farm at Lower Jemseg, near Gagetown, a property Elisabeth would name Meadowlands; the family moved there the following year.

Having considered life’s options and realized that, for her, marriage was not a desirable one, at the age of 29 Scovil enrolled at the Boston Training School for Nurses. Although nursing schools at the time accepted only students of good background and morals, nursing was in its infancy as a respectable profession. According to family lore, as Scovil was waiting with her mother on a hard bench outside the interview room of the school, the elder woman had whispered that she would sooner her daughter became a housemaid than a nurse.

Scovil’s optimism and application helped her to develop a real love for and dedication to her work (she would reminisce in old age that the daily floor mopping she did as a student was a little like skating). In 1879, only halfway through her two-year course, she wrote an article on “Domestic nursing” that was published in Scribner’s Monthly, earning her a generous fee. This success launched what she called “my modest literary career.” The following year the Christian Union accepted nine contributions, eight relating to home care for the sick. After Scovil graduated in 1880, she wrote an article for the Youth’s Companion on learning to become a nurse; it was estimated, she said, that the piece brought over 1,000 applications for admission to the training school, and it won her the thanks of the institution’s board of directors.

Upon qualifying in her profession, Scovil took a position as head of the infirmary at St Paul’s School in Concord, N.H., where she remained for eight years. She then served as superintendent of nursing at the Newport Hospital in Rhode Island until 1894. After a sojourn in New Brunswick – one of two extended return visits she made during her American years – she went back to St Paul’s. She was active in the Nurses’ Associated Alumnae of the United States. Concerned to promote her profession, she told its convention in 1900, “It is by … earnest devotion to duty that we must raise our calling in the eyes of the world.”

Scovil’s career in journalism had continued during these years. In 1888–91, for example, her 15-article series, “Talks by a trained nurse,” appeared in Peterson’s Magazine. Many of her submissions at this time, and subsequently, consist of recipes, and she seems to have been something of a nutritionist, with a particular interest in the diet of children and convalescents. After publishing two items in the Ladies’ Home Journal in the spring of 1890, she was asked to serve as one of its advisory and contributing editors and was placed in charge of the mothers’ department. Scovil also became an associate editor with the American Journal of Nursing when it was founded in 1900. From November 1901 to February 1921 she provided a monthly feature, “Notes from the medical press”; for this column she scanned several journals aimed at doctors, selecting information she thought nurses ought to know. In October 1917 she began to write “News from the medical world” for the Canadian Nurse. This series was joined, and eventually superseded, by another, “The world’s pulse,” which – until it ended in September 1924 – presented more general news items. Both nursing journals commented on her dependability.

As her journalistic activities increased, Scovil had begun publishing, in 1888, her 24 known books dealing with nursing, parenting, children’s interests, and spiritual guidance. The second of these, A baby’s requirements (1892), went through at least eight editions and was praised by the American Journal of Nursing for its practicality and its “unusually clear and simple style.” Her last book, Common ailments of children (Philadelphia), would appear in 1930, when she was 81. Her publications made her known across North America and in Great Britain. In Canada, her work on the proper diet for infants was acknowledged by Adelaide Hoodless [Hunter*], the well-known promoter of home economics. In 1904 Scovil was listed in London’s Gentlewoman as one of “the English-speaking women who have achieved distinction in work for the public good, or in the arts and professions.”

Not only a prolific writer, Scovil was also a social activist. After the vicereine of Canada, Lady Aberdeen [Marjoribanks], founded the National Council of Women of Canada (NCWC) in 1893 – when she also became president of the International Council of Women (ICW) – she enlisted Scovil’s participation in both bodies. Scovil presented a number of papers to the NCWC in its early years. In 1899 she would attend the ICW meeting in London; there she visited Florence Nightingale, whom she had first met two years earlier. (On a previous occasion, as a member of an American delegation of nurses, she had had tea with Queen Victoria.) In 1897 Lady Aberdeen asked Scovil to speak in Saint John, Ottawa, and Victoria on behalf of her fledgling Victorian Order of Nurses for Canada. Family tradition has it that when women on the prairies heard that Scovil was taking the train to British Columbia, they gathered at stations to thank her for her book Preparation for motherhood (Philadelphia, 1896), which had transformed their lives.

After her brother Morris’s wife died of diabetes in 1903, Scovil gave up her active nursing career and returned to Meadowlands. There she continued her writing while she brought up her five nieces and nephews and established a contented life with her brother. She maintained her professional interests. For a time she conducted classes in home nursing in Saint John, and she attended meetings of the Canadian Society of Superintendents of Training Schools for Nurses and the Canadian National Association of Trained Nurses [see Mary Agnes Snively]. During the First World War the Canadian Nurse published three of the informative papers she delivered before these bodies. In 1917, after the federal government of Sir Robert Laird Borden (which she supported) had extended the franchise to the immediate female relatives of servicemen, she encouraged eligible women in Gagetown to make their views known by going to the polls.

Because she had made shrewd investments and had been paid for her work with the Ladies’ Home Journal partly in Curtis Publishing Company stocks, which soared in value, Scovil became, as she informed a grandniece, a millionaire. She was extremely generous to family members and to such causes as the roof fund for her local church and the Pickett Memorial Fund, started in 1910 by her friend and fellow nurse Lucy Vail Pickett to help sick clergymen and their families. Scovil would later become the secretary and organizer of this second fund, which was eventually named the Pickett Scovil Memorial Fund and still exists more than a century later. Active in other church work, in 1906 she had been made a life member of the local Woman’s Auxiliary to the Missionary Society of the Church of England in Canada, and in 1919 she was chair of the diocesan women’s committee of the Anglican “Forward Movement.”

At some point Scovil had become owner of Meadowlands (she had threatened legal action against two of her brothers if they insisted that the farm be shared by the whole family). In 1923 the property passed to a younger generation, and she and Morris moved to Fredericton. Fond of travelling, she visited Alaska, South Carolina, Italy, England, Scotland, and Ireland over the years. Even after the financial crash of 1929, she and her brother could afford to spend six months of each year with one of Morris’s sons in the United States and six months with his son in England, where one of his daughters also lived. She was in the process of writing a book of one-page stories for children when, in her 86th year, she died of unrecorded causes at her nephew’s home in Bishop’s Stortford. Much praised in obituaries, she was thought to be the oldest graduate nurse in North America. Though she had always insisted on the truth, Scovil allowed one lie in death: she arranged to have placed on her gravestone the inscription “Born at Meadowlands, New Brunswick, Canada” because she had such affection for the farm. In fact, she was born in Saint John, as the family bible states. Perhaps she can be forgiven.

This biography is based in part on oral tradition, on unpublished family correspondence in the author’s possession, and on photocopies of documents, including pages of a family bible, provided by the late Charles E. Karsten of Readfield, Maine, a great-nephew of the subject.

Elisabeth Robinson Scovil is the author of In the sick room: what to do, how to do, and when to do for the sick: the art of nursing (Springfield, Mass., [1888]) and A baby’s requirements (Philadelphia, 1892). Her other books were all issued by the Henry Altemus Company of Philadelphia and are listed at “Henry Altemus Company”: www.henryaltemus.com (consulted 31 Oct. 2016). Family tradition holds that she wrote a work entitled The littlest loyalist and a history of the Kingston peninsula in New Brunswick, but no trace of these works has been found and they may not have appeared in print.

Scovil also published widely in North American periodicals. Her article on “Domestic nursing” for Scribner’s Monthly (New York) appeared in vol.8 (May–October 1879): 786–89, and her series of 15 articles entitled “Talks by a trained nurse …,” for Peterson’s Magazine (Philadelphia), were published in vols.94–100 (1888–91). These items, as well as articles she wrote for the Christian Union (New York), the Ladies’ Home Journal (Philadelphia), the Youth’s Companion (Boston), and other periodicals can be found at “ProQuest”: www.proquest.com (consulted 2 Nov. 2016). Not included there, however, are her contributions to Good Housekeeping (Holyoke, Mass., etc.), the American Journal of Nursing (Philadelphia), or the Canadian Nurse (Ottawa, etc.). A list of her articles in the American Journal of Nursing can be found at Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc., “AJN: American Journal of Nursing,” previous issues: journals.lww.com/ajnonline/pages/issuelist.aspx (consulted 2 Nov. 2016).

Bishop’s Stortford Old Cemetery (Eng.), Tombstone. N.B. Museum (Saint John), S119-119B, F 100-105 (handwritten biographical article by M. G. Otty, 30 April 1932). Calgary Herald, 4 Dec. 1934: 9. M. G. Otty, “Elisabeth Robinson Scovil: fifty-five years a nurse,” Canadian Churchman (Toronto), 28 March 1935: 201. St. John Morning Telegraph (Saint John), 5 Dec. 1868. American Journal of Nursing, 1–23 (1900–23). Doris Calder, All our born days: a lively history of New Brunswick’s Kingston peninsula (Sackville, N.B., 1984). Canadian Nurse, 7–20 (1911–24). Ladies’ Home Journal, 1890–1906. Mass. General Hospital Training School for Nurses [Booklet listing all nursing graduates from 1875 to 1902] ([Boston], n.d.; copy in the possession of Hughena McNeil, Fredericton). “Obituaries,” American Journal of Nursing, 35 (1935): 90–93. “Obituary,” Canadian Nurse, 31 (1935): 40. S. E. Parsons, History of the Massachusetts General Hospital Training School for Nurses (Boston, 1922). “The roll of honour for women,” Gentlewoman (London), 22 Oct. 1904: 677. G. C. M. White, “Miss Elizabeth Robinson Scovil,” Canadian Nurse, 20 (1924): 393–94.

Cite This Article

Virginia Scovil Bjerkelund, “SCOVIL, ELISABETH ROBINSON (Elizabeth),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 31, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/scovil_elisabeth_robinson_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/scovil_elisabeth_robinson_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Virginia Scovil Bjerkelund |

| Title of Article: | SCOVIL, ELISABETH ROBINSON (Elizabeth) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2022 |

| Year of revision: | 2022 |

| Access Date: | December 31, 2025 |