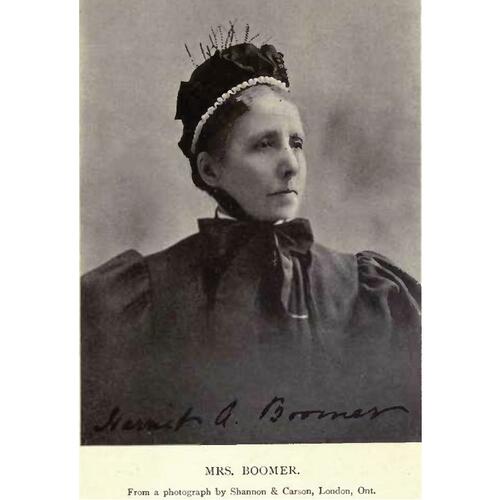

![Description English: Mrs Harriet A Boomer by Shannon & Carson Date 8 June 2011 Source Morgan, Henry James Types of Canadian women and of women who are or have been connected with Canada : (Toronto, 1903) [1] Author Shannon & Carson, London, Ont.

Original title: Description English: Mrs Harriet A Boomer by Shannon & Carson Date 8 June 2011 Source Morgan, Henry James Types of Canadian women and of women who are or have been connected with Canada : (Toronto, 1903) [1] Author Shannon & Carson, London, Ont.](/bioimages/w600.7388.jpg)

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

MILLS, HARRIET ANN (Roche; Boomer), author and social activist; b. 10 July 1835 in Bishop’s Hull, England, second daughter of Thomas Milliken Mills, a solicitor, and Ann Benton; m. first 11 March 1858 Alfred Robert Roche in Staplegrove, England; m. secondly 17 Nov. 1878 Michael Boomer* in New York City; she had no children; d. 1 March 1921 in London, Ont.

Little is known of Harriet Mills’s early life, but she was well educated, most likely by her mother, who found it necessary to take in pupils after being widowed at age 25. Harriet and her sister Mary Louisa came to Canada in 1851 when their mother accepted the principalship of St Cross school at Red River (Man.). In 1857 Harriet and her mother returned to England – Mary Louisa stayed, having married Francis Godschall Johnson*. Mrs Mills took a position at Queen’s College in London. Harriet attended classes there, likely until she married Alfred Roche, a geologist who had spent some time in Canada, and moved to Hertfordshire. In 1875 the couple went to the Transvaal to inspect Roche’s mining interests; he became ill and died at sea in 1876 on the way home. To help support herself, Harriet produced On trek in the Transvaal: or, over berg and veldt in South Africa (London, 1878).

In 1878 she married the Reverend Michael Boomer, principal of Huron College in London, Ont., where she quickly became involved in church and fund-raising activities. To aid the college, for instance, she wrote Notes from our log in South Africa . . . (London, Ont., 1880). Widowed again in 1888, she was instrumental that year in establishing the London Convalescent Home and was elected president of its board of management. In October 1893 she attended the founding meeting in Toronto of the National Council of Women of Canada, which would become her main focus; she was a leader at the inaugural meeting on 14 Feb. 1894 of the London Local Council of Women. Presiding over both gatherings was Lady Aberdeen [Marjoribanks*], wife of the governor general and president of the National Council. Harriet visited the vice-regal couple frequently and was proud of her close friendship with them. Lady Aberdeen, in turn, regarded her as “a great feature in our National Council, for her tact & sense of humour has helped us over many a rough place.” Harriet was president of the London council from 1897 to 1920, undoubtedly a record among local presidents. A vice-president for Ontario, she attended most annual meetings of the National Council, often presenting motions and papers, and in 1899 she travelled to England for the International Congress of Women.

The concern of Harriet and the London council for health care was evident in many areas. When the city proposed to build a new hospital without a children’s wing, Harriet was instrumental in 1898 in securing funding for the children’s pavilion at Victoria Hospital, which incorporated the old structure. In 1906 she and the council played a leading role in setting up a branch of the Victorian Order of Nurses, with Harriet as president of its board. In 1919, when the Imperial Order Daughters of the Empire proposed to replace the crowded pavilion with a new war memorial hospital for children, the London council fully supported the fund-raising for the project.

They were proud of their patriotic efforts. In 1900 Harriet had established London’s first Red Cross Society to send aid to soldiers in the South African War. The society lapsed but it was revived in 1914 with Lillian, Lady Beck, as president and Harriet as honorary president. During World War I it was responsible for raising almost $1 million. In September 1914 Harriet served as advisory editor of the Belgian Relief Fund issue of the London Advertiser. Ever the imperialist, she persuaded the London Board of Education to purchase 5,000 copies of a booklet, The history of our flag by Clementina Fessenden [Trenholme*], for distribution.

A firm believer in the education of females, Harriet felt there should be more opportunities for women worldwide. There was a need, she maintained in the National Council’s annual report, “to cultivate more and more of the business faculty of which men are supposed to have a monopoly, but of which we women are not bereft.” It was especially important that females succeed scholastically and pursue the careers that had opened up for them in the 1900s. The study of domestic science was seen as particularly valuable. Harriet’s council exerted pressure on the London school board to introduce it, a goal that was achieved in 1905.

Feminists of the late 19th century believed that it was necessary to have women on school boards since they were the natural educators of children. Harriet logically pointed out to the London board that women had been successful in charitable works and served on boards elsewhere. Thus, in 1898 she was appointed as London’s first female trustee; during her three-year term she “learnt woman’s hardest lesson – how to be silent.” Perhaps she was not entirely successful in this respect since she was not reappointed and the position was allowed to lapse until 1919.

A devout Anglican, she took an active role in many church organizations, including the Mother’s Union of Cronyn Memorial Church, the Woman’s Auxiliary to the Missionary Society of the Church of England in Canada, and the Women’s Christian Association. According to David Williams*, the bishop of Huron, “The inspiration for all her work was her strong faith and loyalty to Jesus Christ.”

Harriet Boomer’s long years of unselfish service to religious, charitable, and educational causes in London demonstrated that women had a role to play in public affairs, not just in the private sphere. Her forcefulness made enemies, but in her time a woman had to be forceful to be heard. Perhaps her greatest talent was the ability to face all situations, according to the Advertiser, “with an indomitable courage, [and] unfailing laughter that kept youth ever bright in her heart.” She died at age 85 and was buried in Woodland Cemetery.

In addition to the works cited, Harriet Ann Boomer is the author of Little Miss Ellerby and her big elephants: respectfully dedicated to all whom it may concern ([London, Ont., 188?]), a pamphlet on a juvenile dream that is really a call for united action on reducing parish debt.

AO, RG 22-321, no.15080; RG 80-8-0-826, no.21017. GRO, Reg. of marriages, Taunton, 11 March 1858. London Public Library, London Room (London, Ont.), Materials pertaining to Harriet Boomer. London Advertiser, 5 March 1888; 15 Feb. 1894; 2, 4 March 1921. London Free Press, 3 Dec. 1897, 8 April 1898, 17 March 1900, 25 Jan.1902, 7 March 1952. F. H. Armstrong, The Forest City: an illustrated history of London, Canada (Northridge, Calif., 1986). T. F. Bredin, “The Red River Academy,” Beaver, outfit 305 (winter 1974): 10-17. Canadian who’s who, 1910. W. E. Corfield, To alleviate suffering: the story of Red Cross in London, Canada, 1900-1985 (London, 1985). Joan Kennedy, “The London Local Council of Women and Harriet Ann Boomer” (ma thesis, Univ. of Western Ont., London, 1989). [I. M. Marjoribanks Hamilton-Gordon, Marchioness of] Aberdeen [and Temair], The Canadian journal of Lady Aberdeen, 1893-1898, ed. J. T. Saywell (Toronto, 1960). National Council of Women of Canada, Annual report ([Ottawa]), 1897. J. R. Sullivan and N. R. Ball, Growing to serve: a history of Victoria Hospital, London, Ontario (London, 1985). Types of Canadian women . . . , ed. H. J. Morgan (Toronto, 1903).

Cite This Article

Joan Kennedy, “MILLS, HARRIET ANN (Roche; Boomer),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 2, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mills_harriet_ann_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mills_harriet_ann_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | Joan Kennedy |

| Title of Article: | MILLS, HARRIET ANN (Roche; Boomer) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2005 |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | January 2, 2026 |