Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

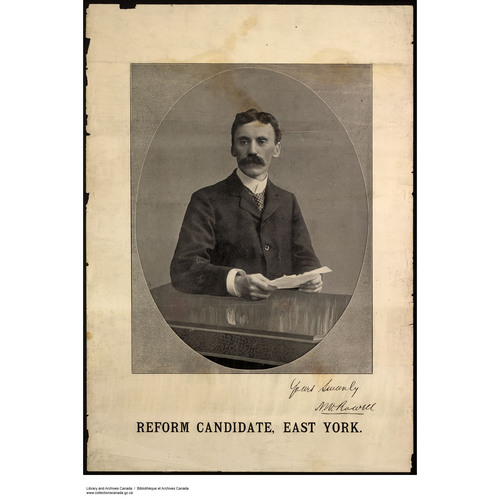

ROWELL, NEWTON WESLEY, lawyer, churchman, politician, and judge; b. 1 Nov. 1867 on a farm near St John’s (Arva), Ont., fourth child and second son of Joseph Rowell and Nancy Green; brother of Sarah Alice Rowell*; m. 27 June 1901 Nellie Langford in Owen Sound, Ont., and they had three sons and one daughter; d. 22 Nov. 1941 in Toronto.

Newton Rowell’s family was rooted in the moderate Reform movement of Robert Baldwin* in Upper Canada and the social conservatism of British Wesleyanism; these traditions shaped his early life and informed his later years. His father, a farmer and Methodist lay preacher, had migrated from Cumberland, England, in 1842 with his wife and several children and taken a farm at St John’s, close to London. His second marriage was to Nancy Green, 20 years younger than Joseph and eldest daughter of a local family of English-Irish origins. Following six years in the village school, Newton took a short commercial course in London early in 1883, and then worked there for three years in an uncle’s wholesale dry-goods business. His maternal grandmother had often regaled listeners with tales of how her Reformer father, Henry Coyne, had led resistance against the autocratic settlement methods of the “Lake Erie baron,” Thomas Talbot*, but had strongly opposed the rebellion of 1837-38 [see William Lyon Mackenzie*]. Her stories gave her grandson an early introduction to history; lectures at the London Mechanics’ Institute and the home reading courses of the Chautauqua movement helped him to pass high school matriculation examinations in 1886. By this time, he had decided to become a lawyer.

That autumn Rowell, too poor to attend university, took the commonly followed route of joining a legal firm. Experience and study at Fraser and Fraser would prepare him to enter his chosen profession. In the fall of 1890 he made a three-months’ trip to western Canada to collect debts owed to London farm-implements distributors, travelling by Great Lakes steamers to Port Arthur (Thunder Bay), then on the Canadian Pacific Railway to Vancouver, and finally home through the United States. An Upper Canadian had become a Canadian with a vision of a “new Ontario” in the west.

He moved to Toronto in the spring of 1891 and wrote the exams of the Law Society of Upper Canada, standing second in a class of 40. Called to the bar, he joined the firm of Isidore Frederick Hellmuth, one of the most distinguished lawyers in the province. Initially, most of his work was in property and corporation law. One of his earliest cases was fought against Britton Bath Osler*. Others in Toronto practice included Samuel Hume Blake*, Ebenezer Forsyth Blackie Johnston*, and Zebulon Aiton Lash*.

Rowell’s rise in the legal profession was accompanied by increasing prominence in the Methodist Church and in the Liberal Party. In November 1889 he had been designated a Methodist lay preacher, in 1892 he was the youngest man ever elected a lay delegate to the church’s Toronto Conference, and he was in constant demand as a lay preacher and champion of the temperance movement. Despite a rather thin, high-pitched voice and a reputation in some quarters for excessive seriousness and an addiction to statistics, he could command audiences in diverse settings. He spoke on behalf of younger Liberals at a testimonial dinner when Sir Oliver Mowat* retired from the premiership in 1896. In the federal election held on 7 Nov. 1900 he was defeated in York East, near Toronto, by Conservative William Findlay Maclean*. A primary issue in the contest was Canada’s part in the South African War. Although Rowell thought otherwise, he did not publicly deviate from Prime Minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier*’s assurances that sending volunteers to South Africa would not be a precedent. Rowell believed that participation in the conflict could demonstrate Canada’s growing importance in the empire, and the fact that English and French soldiers were fighting side by side might break down cultural barriers. Ironically, his campaign was weakened by English-French acrimony arising from the attitudes and utterances of Quebec mp Joseph-Israël Tarte*.

Admiring the way Rowell accepted his defeat was Nellie Langford, who had graduated with a degree in modern languages from Toronto’s Victoria University in 1896. Her father was the Reverend Alexander Langford, in whose home Rowell had been a welcome visitor over some years. Their marriage in June 1901 was followed by a honeymoon in Britain, where they visited places of religious and literary interest. They were in London in September for the third Ecumenical Methodist Conference. To delegates from around the world Rowell delivered a passionate speech on the mission of Canadian Methodism to connect the Britons and North Americans, “the two great branches of the Anglo-Saxon race ... one in Providential design and purpose for the world’s evangelisation.” He enjoyed the opportunity to meet church leaders and listened to debates on how Methodist social concerns should be expressed in an industrial society. Soon after his arrival in Toronto he had begun working at the Fred Victor Mission, which promoted welfare and evangelism among the poor and was financed chiefly by Hart Almerrin Massey*, and he was active in the fight against Sunday streetcars, which was finally lost in 1900. He became superintendent of Metropolitan Church’s Sunday school shortly after his marriage; at the 1902 General Conference he opposed any change to the Methodist discipline with its proscription of dancing, card-playing, and theatre-going, and he was against making it easier for women to be elected to church courts. Faith was important in the home he built in the exclusive Rosedale district in 1904: there were family prayers before breakfast, and the children, William Langford and Mary Coyne, listened to their father tell Bible stories on Sunday evenings. Religious certainty provided consolation when, in 1908, his second son, Edward Newton, died suddenly and inexplicably at the age of seven months.

The professional side of Rowell’s life flourished. Appointed a kc in 1902, he had become the senior partner in his own law firm, Rowell, Reid, and Wood, in the following year. Most of his cases concerned the interests of companies financed by American capital invested in northern Ontario, some of them closely related to the Liberal Party. He had been a key figure in restructuring the businesses of entrepreneur Francis Hector Clergue* through the creation of the Consolidated Lake Superior Corporation and subsequently represented the Ontario government on its board of directors. Solicitor for the Algoma Central Railway and for the Nipigon Pulp and Paper Company, he had defended the expropriation procedures of the town of Kenora against the Keewatin Power Company and the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1907-8.

Early in 1909 Rowell engaged in public battle against the general superintendent of the church and chairman of the board of regents of Victoria University, Albert Carman*. The issue was whether George Jackson, a Methodist minister from Britain, was qualified to be professor of English Bible. In 1906 Rowell and Joseph Wesley Flavelle* had been instrumental in bringing Jackson to Canada as minister to the wealthy Sherbourne Street Church [see Nathanael Burwash*]. With other members of the board, they welcomed Jackson’s understanding of the Bible as the revelation of spiritual truth and not as history or science. For 18 months Rowell prepared for “the Jackson case” as carefully as for any legal defence. At the General Conference of the church in 1910 Rowell, other Jackson supporters, and higher criticism carried the day. His most immediate concern had been that “a barren theological controversy” would damage the national congress of the Laymen’s Missionary Movement in Canada, held in Toronto from 31 March to 4 April 1909. As the organization’s moving spirit, Rowell had declared to an audience of some 4,000 that Canada had a providential mission in evangelizing the world. In June 1910 he had been in Edinburgh as a delegate to the World Missionary Conference, the largest ecumenical gathering in Christian history.

Although Rowell had rarely appeared on political platforms after the defeat of Liberal premier George William Ross*’s government in 1905, he had devoted much thought to political developments. What spurred him into active participation was Laurier’s achievement, announced in the House of Commons on 26 Jan. 1911, of an agreement permitting free trade in natural products with the United States. A revolt by Liberal business leaders such as Sir Byron Edmund Walker* and John Craig Eaton* was based on the fear that reciprocity would eventually include manufactured goods. In the September election Rowell campaigned vigorously across Ontario for the agreement. A second issue was imperial defence; he fully supported Laurier’s plan for a navy available to Britain with the consent of the Canadian parliament. In October, after the rout of the federal Liberals, Conservative premier Sir James Pliny Whitney* called an Ontario election. The head of the provincial opposition, Alexander Grant MacKay, had abruptly resigned because of scandalous accusations, and the Liberals turned to Rowell, regarded as incorruptible. He accepted on assurances that the party was ready “to take advanced ground on the question of temperance as well as other questions of social reform.” The press aptly portrayed the new leader as “Moses in the wilderness.” On 11 December he won a safe seat in Oxford North; his party secured 20 others, a gain of two.

Now leader of the opposition, Rowell took on the task of party reorganization. He had advice and considerable financial support from a group that included Alfred Ernest Ames*, Edward Rogers Wood, James Henry Gundy*, William Edward Rundle, Frederick Herbert Deacon, and the publisher of the Toronto Daily Star, Joseph E. Atkinson, Methodists all. The Liberals could do little except criticize the Whitney government’s policies. These included Regulation 17, which limited the teaching of French in schools [see Philippe Landry*], and a workmen’s compensation act. During the June 1914 election a better-run party made its slogan “abolish the bar.” Rowell declared that the battle was between “organized Christianity” and “the organized liquor interests.” The result was a gain of only four seats. As long as the wealthy could drink in their private clubs, most of Ontario’s working-men were not prepared to give up their beer in return for promises of social insurance, nor did they wish to extend the franchise to women, who were believed to favour prohibition. But a little more than two years later the Ontario Temperance Act, unanimously passed, would end the sale of all liquor, and in February 1917 the government, now headed by Sir William Howard Hearst, would give women the vote, although not the right to sit in the legislature as a motion made by Rowell would have allowed.

The reason for the patriotic ban of liquor sales and the enfranchisement of women was not far to seek. A few weeks after the 1914 election Canada was in Britain’s war against Germany. Rowell was active in establishing bipartisan agencies to mobilize Ontario’s war effort. In speeches he frequently declared that working-men could not be asked to sacrifice their lives unless their society’s post-war conditions were to be better than those of the present, when 65 per cent of the population owned only 5 per cent of the wealth. He saw Canada’s initial response to the war as magnificent, but recruiting became more difficult, especially in Quebec. Early in 1916 he welcomed Prime Minister Sir Robert Laird Borden*’s announcement that the armed forces would be increased to 500,000. Laurier had agreed to a one-year parliamentary extension to avoid an election that would exacerbate tensions caused by attitudes towards recruitment and the war that placed Quebec in opposition to the rest of Canada.

A group of Toronto Liberals wanted Rowell to assess Britain’s situation and under Peter Charles Larkin* they raised the money for a two-month trip. Although reluctant to go for personal reasons – his third son, Frederick Newton Alexander, was only six weeks old and Nell was still recovering from the birth – he sailed for London at the end of June. There and in Paris he gained first-hand information about the war efforts of Britain and France and visited the front. He delivered his lengthy report in September, but had little hope that the prime minister would ensure “the radical change” needed in a government whose prosecution of the war was weakened by “indecision, incapacity, and graft.” Borden, who had to cope with the difficulties caused by Minister of Militia and Defence Sir Samuel Hughes*, was not particularly receptive. However, Rowell made no public criticism. He was convinced that an effective war effort demanded the cooperation of all parties. After repeated efforts to persuade Laurier and then Ontario Liberals such as George Perry Graham to enter a coalition, Rowell finally accepted Borden’s invitation to do so himself just before the formation of the Union government was announced on 13 Oct. 1917. Rowell had stipulated that leading Liberals from the west and the Maritimes must also join. Among those who were won over were James Alexander Calder*, Thomas Alexander Crerar*, Arthur Lewis Watkins Sifton*, Frank Broadstreet Carvell*, and Alexander Kenneth MacLean; regrettably, no French Liberal from Quebec could be found to support conscription. Although some, dubious that principles and policy could be more important than party, questioned his motives, the Toronto Liberals who supported Rowell remained solidly behind him. They had believed that they were coaching a future prime minister, but they understood that his commitment to conscription, which had come into effect in August, might limit his political prospects.

Rowell entered the Union government as president of the Privy Council, a position usually held by the prime minister, and as vice-chairman of the War Committee, with Borden as nominal chairman. He thus had primary responsibility for organizing the war effort, including enforcement of conscription. At first he relied heavily on the advice of his close friend Rundle, president of the National Trust Company. Both men fully intended to show that the new government, as the Globe (Toronto) urged, had the will “to lay a firm hand on the machinery of Big Business, and make it work for the State,” although Flavelle had already made the Imperial Munitions Board enormously productive.

After an election was called for 17 December, Rowell had less time to give to the War Committee. A most difficult problem was deciding who would run for the Unionists in Ontario: at dissolution the Conservatives held 70 seats there, the Liberals 12. He tackled the problem with John Dowsley Reid*. The sincere commitment of Borden and Rowell to equality of party representation was rarely shared at local levels, a fact Rowell was slow to realize. He eventually ran in Durham, east of Toronto, where the sitting Conservative member, Robert Alexander Mulholland, was persuaded to withdraw on a promise of appointment to the Senate. In a campaign that was both ferocious and divisive Rowell’s oratorical prowess reached its zenith. He declared that he was willing to accept any political label if he could help the men “fighting for Canada and pouring out their very life blood on the fields of France and Flanders.” Voters, he said, were deciding “the future of Canada, the future of our empire, and the cause of human liberty.... It is the struggle of the Pagan belief against the Christian.... A man in casting his ballot reveals to his God his own character.” The War-time Elections Act, passed in September [see Arthur Meighen*], had enfranchised the immediate female relatives of those actively serving in the armed forces, while “enemy aliens” naturalized since 1902 had been deprived of the vote unless they had close male relatives fighting abroad, a measure of which Rowell had disapproved. The Methodist Church, whose pulpits were widely used as recruiting platforms, strongly supported conscription of both men and wealth and cited Rowell as a patriotic Liberal and an example to be followed. The election results divided Canada between French and English as never before: Unionists held 153 seats and the Laurier Liberals 82, all but 20 of them in Quebec. Rowell, who won Durham with a substantial margin, declared that if French Canadians would now fight for their country, Canada would enjoy a unity previously unknown.

As the new parliament opened on 18 March 1918, Rowell was under doctor’s orders to take life more easily; his rather frail health had been taxed by chronic overwork. During the debate on the speech from the throne after he had gone home exhausted, Charles Murphy*, an Irish Catholic and former member of the Laurier cabinet, delivered a two-hour denunciation of Rowell’s whole career, centring on a charge of “conspiracy” to overthrow Laurier on behalf of a “cult of commercialized Christianity.” Murphy’s purpose was clear: he wanted to reduce Rowell’s influence, ensure his exclusion from post-war politics, and make certain that the rift in the Liberal Party, both nationally and provincially, would be permanent. Rowell decided not to waste precious energy on a reply. All that mattered was prosecution of the war. The most urgent requirement was the enforcement of the Military Service Act. In the face of riots in Quebec City from 28 March to the night of 1-2 April [see Georges Demeule*; François-Louis Lessard*] and discontent everywhere with methods of granting exemptions, the government maintained that the act was being administered impartially. Returning to his responsibilities for the War Committee, Rowell pushed for greater cooperation from organized labour. He received only a lukewarm response. The voluntary mobilization of industry proved no easier, although the appointment of a War Trade Board and a Canadian War Mission in Washington had potential. His vow to levy substantial taxes on business profits brought him into sharp conflict with some of his friends such as Gundy, an investment dealer recently appointed to the board. Gundy resisted Rowell’s determination to tax meat packers at the rate of 11 per cent on investment; their mutual friend, Flavelle, who had recently received a baronetcy, had also argued that the proposed rate was too high, although a royal commission had found that in 1916 Flavelle’s enterprise, the William Davies Company, made an 80 per cent return on meat sales to Britain, a profit Flavelle contended was due to increased volume. In March 1918 an order-in-council limited packers’ profits to Rowell’s preferred rate. The increases in other taxes on business and in personal income tax were less than he had suggested; aware of growing unrest among labourers, he had hoped to equalize the financial sacrifices demanded by the war. However, as chairman of a special house committee on veterans’ pensions, he was gratified by agreement to the most generous pension scale provided by any of the Allies. He applauded the government’s extension of the operation of the Civil Service Commission to the 35,000 federal employees outside the national capital as “the most radical [reform of a civil service] ... that has ever been made at one stroke in any country.” This measure was a step towards eliminating patronage, as was the broadening of the War Purchasing Commission’s jurisdiction to all government departments. He also rejoiced in parliament’s request that the crown cease to confer hereditary titles on Canadians except by consent of the Canadian cabinet [see William Folger Nickle*].

On 27 May 1918 Borden, with Rowell, Calder, and Meighen, sailed from New York to attend meetings of the imperial war cabinet and the Imperial War Conference in London. The prime minister wished to demonstrate his commitment to equal representation between Conservatives and Liberals, and valued Rowell’s knowledge on foreign affairs. Rowell departed for home at the end of July after visiting Canadian forces in France and devoting weeks of strenuous effort to gathering useful information. He concluded that what Borden already believed was correct: British politicians, bureaucrats, and generals had little to teach their Canadian counterparts about running a war or an empire. The Canadian contribution to the war was a powerful argument for changing the imperial structure.

The country to which Rowell returned was more restless than it had been before his departure. Travelling in western Canada, he found hostility to the government everywhere when he examined the work of the Royal North-West Mounted Police, which was under the jurisdiction of the Privy Council and had been charged with implementing a ban on organizations, selected in his absence, that advocated the overthrow of government or private property. Rowell had to argue with colleagues such as minister of justice Charles James Doherty* and Charles Hazlitt Cahan that the Social Democratic Party of Canada was similar to the British Labour Party. It was not, he claimed, a social menace and it should not be banned. His viewpoint eventually prevailed.

At the war’s end on 11 Nov. 1918 Rowell, as president of the Privy Council, led the service of thanksgiving on Parliament Hill. Borden was already on his way to Europe to ensure that Canada had a voice in the making of peace. Rowell told the quietly jubilant crowd: “To-day marks the close of the old order and dawn of the new. It is the coronation day of democracy.” During the next few weeks he made speeches hailing “the new order,” whose hallmarks would be the “defence of the weak in every walk of life” by governments and vastly more cooperation between employers and employees. Many of Rowell’s Conservative colleagues in cabinet, such as minister of finance Sir William Thomas White*, were less than enthusiastic about much of this agenda, which included subsidized housing, health promotion, and improved educational opportunities. Methodist Conservatives were even more alarmed when pronouncements by their church began to sound as if it had become a socialist body. The report of the Committee on Evangelism and Social Service, for instance, had advocated a greater role for labour in managing industry, a national system of old-age insurance, and the nationalization of natural resources.

Major government decisions had to wait until Borden returned from Britain, where he was defending Canada’s autonomy with Rowell’s hearty approval. Since joining the cabinet, he had revised his initially tepid opinion of Borden, with whom he had worked well. They agreed on Canada’s position within the empire, and Borden relied on Rowell to formulate much of the government’s domestic agenda. In the prime minister’s absence he had the unenviable task of trying to explain to a divided cabinet and a sceptical public the dispatch of 4,000 Canadian troops under James Harold Elmsley on an imperial venture to Siberia. Rowell changed his mind on the merit of the original decision, but after Borden’s return he continued to carry publicly much of the burden for justifying an obscure action through the Department of Public Information, which had been created late in 1917 as part of the Privy Council Office.

In June 1919 Winnipeg workers made clear the force of their demands for a better world and staged a general strike, the biggest labour demonstration in Canadian history [see Mike Sokolowiski*]. Rowell, well known to be sympathetic to labour, was in a decidedly awkward position. He praised the democratic and law-abiding intentions of the majority of workers and their leaders, yet he also expressed the fears of the Winnipeg business community that the Bolshevik ideas of the One Big Union had infiltrated the leadership of the strike and that a full-blown revolution was brewing in western Canada. Although the strike was remarkably peaceful, when violence erupted briefly he defended the use of the RNWMP to restore order. Quebec Liberals, especially Lucien Cannon and Ernest Lapointe, made sure that Rowell was vilified for both the temporary loss of order and the means used to deal with it. In the fall of 1919 Rowell had the opportunity to promise better relations between workers and employers on the international stage. Together with the minister of labour, Gideon Decker Robertson*, he spoke for the Canadian government at the founding conference of the International Labour Organization in Washington, where he was at loggerheads with Conservative Methodist Silas Richard Parsons*, a representative of Canadian business who would have nothing to do with unions of any type. Rowell made clear both his government’s responsibility for setting workplace policy and his country’s independence of American decisions.

By the end of the summer of 1919 the federal government had established Canada’s first Department of Health with Rowell as the minister charged with its organization. It was a weak version of what he had wanted to call the Department of Social Welfare: both sides of parliament had put up stiff resistance to “ill-defined” provisions for extending federal influence into matters of provincial jurisdiction. His work as chairman of a cabinet committee on housing suffered a similar fate when the federal government was left with only the power to advise the provinces. He also failed to persuade his colleagues that veterans whose university studies had been interrupted by war service should receive financial assistance to complete their education, or that federal prohibition measures of 1916 should be extended past 31 Dec. 1919 (in the next year British Columbia allowed limited liquor sales, and other provinces soon followed).

On 1 July 1920 Borden announced his retirement and was succeeded by Meighen as prime minister and Conservative leader. Rowell believed that the Union government had enacted “more real progressive legislation ... than any other Government in Canadian history,” and he could not be part of the new administration. Foreseeing that Conservative policies would predominate and his attitudes towards social reform would be considered too “radical,” he had no difficulty in resisting Meighen’s repeated urging to join his government, which assumed the name National Liberal and Conservative Party. Rowell resigned on 10 July, when the new administration took office. A few days later he and Nell sailed for a holiday in England. Their plans were radically altered by the suggestion of Leopold Charles Maurice Stennett Amery, undersecretary of state for the colonies, that they enjoy a relaxed tour of South Africa and the British colonies in eastern Africa, all arrangements to be made by him. After three months of observing fresh landscapes, varying forms of government, race relations, and Christian missions, Rowell, on Meighen’s invitation, joined Sir George Eulas Foster* and Doherty in Geneva to represent Canada at the first assembly of the League of Nations in November.

As he prepared for his role on a world stage he had never felt “less ... like saying of any nation it is Divinely called to lead the world.” He came to believe that the greatest impediments to peace were the instability caused by the Russian revolution, the failure of the United States to join the League of Nations, and the excessive reparations imposed on Germany. He soon acquired a prominent position in the league’s assembly. As part of a consistent effort to assert Canadian autonomy and protect the interests of less powerful nations, he electrified the assembly by declaring that European policies had “drenched this world in blood.... Fifty thousand Canadians under the soil of France and Flanders is what Canada has paid for European statesmanship.” Such oratory offended many Europeans, but it raised Rowell’s prestige at home, especially when leading British newspapers and the American press concurred that he was among “the eight or ten leading figures” at the assembly. Rowell would become certain that the most important achievements of the league were the establishment of the Permanent Court of International Justice and the International Labour Organization.

Early in 1921 he returned to his old law firm and strengthened his connections within the business community; in 1925 he would become president of the Toronto General Trusts Company. Still an mp, he privately advised Meighen, and reported to the house on the significance of the league. Lucien Cannon once more attacked Rowell, this time with the charge that he was encouraging Canada to meddle in affairs that were none of its business. When Rowell urged the immediate appointment of a Canadian ambassador to Washington he was met by more “little Canadianism,” this time from William Stevens Fielding*. Irregularly attending the house, Rowell spent much of his time traversing the nation to speak on international affairs and what he saw as Canada’s role. One of his strongest interests was creating support for the League of Nations, which led him to organize and help finance the League of Nations Society in Canada; it eventually had branches from Halifax to Victoria. Primarily on the strength of his service to the league, the University of Toronto conferred on him an honorary doctorate in June 1921. In November he delivered there the Burwash Memorial Lectures, established in honour of Nathanael Burwash. As always, he aimed to inspire as well as instruct. His approach was historical, his primary theme the conviction that the success of the League of Nations would depend on widespread recognition that a transnational political organization was essential for a peaceful world and human survival. The Christian church had a particular responsibility to foster solutions to international problems, especially through missionary work in education and medicine. The lectures were published as The British empire and world peace (Toronto, 1922).

No honour could compensate him for the greatest personal sorrow of his life. In the spring of 1923 his son Langford, an arts student and athlete at Victoria University, died of blood poisoning. He had planned to study law and enter his father’s firm. Responding to Sir John Stephen Willison*’s letter of sympathy, Rowell said that he took comfort in his faith and the duty to continue “helping all one can.”

Rowell’s work for his church had involved him in discussions on church union since the early years of the century. In 1904 he had been appointed to the first joint committee of the Methodist, Presbyterian, and Congregational churches, and in 1925 he was the leading layman in the creation of the United Church of Canada, which he saw as strengthening Protestantism at home and improving the effectiveness of missionary work overseas. Besides carrying out extensive legal work for the pro-union cause, he addressed rallies in several Ontario centres. He would chair the church’s committee on peace and war; at the third General Council in Winnipeg during the fall of 1928 its report asserted the Christian’s responsibility to encourage peace.

After the election of December 1921 Rowell had observed from the sidelines as Liberal prime minister William Lyon Mackenzie King learned to manage a minority government dependent on Quebec and the new farmer-labour Progressive Party. After winning a substantial majority in September 1926, King proposed to make Rowell minister of customs to clean up serious scandals in the Department of Customs and Excise [see Jacques Bureau*]. He hastily withdrew the offer when Ontario Liberal advisers registered their doubt that Rowell could be elected in any Ontario seat: the French and Irish Catholic vote, the German vote, the anti-prohibitionists, the anti-conscriptionists, and the continuing Presbyterians would all be against him. King recorded that Rowell “displayed a very nice spirit” and agreed to be counsel for the commission King would set up to investigate the department. That fall, while Rowell worked on this assignment, the prime minister was in London at the Imperial Conference, which turned the empire into a commonwealth of autonomous nations. Rowell approved of this result; he would also be satisfied with the commission’s report, tabled early in 1928, containing proposals for the customs department’s reorganization and a recommendation that liquor-export houses be closed.

Rowell had acted as secretary of state for external affairs during several of Borden’s absences; the under-secretary, Sir Joseph Pope*, considered him “the best I have ever served under, at all times accessible, courteous, patient, and one who quickly and decisively makes up his mind, an invaluable quality in a minister.” Eager for the department’s growth, he was delighted when, in November 1926, Charles Vincent Massey* was finally appointed to represent Canada to the United States. Convinced that it now mattered more than ever that Canadians be well informed about the world, Rowell was one of the founding members of the Canadian Institute of International Affairs. The institute, formally established in January 1928, was affiliated with the Institute of Pacific Relations and the Royal Institute of International Affairs.

His freedom from parliamentary duties meant that he had time for the travel he found so enjoyable and intellectually stimulating, with or without family members. In 1922 he had been in France, Germany, Belgium, and the Netherlands; later trips took him to China, Japan, Hawaii, Australia, New Zealand, and Russia. He was often in London because of legal judgements referred to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council. One that received general public attention was the persons case. In 1928 the Supreme Court of Canada turned down his argument on behalf of Emily Gowan Murphy [Ferguson*] and four other Alberta women that the terms of section 24 of the British North America Act, which stated that the governor general was to appoint “qualified Persons” to the Senate, included women. A year later, following presentations by Rowell and others, the Privy Council declared that women were “persons,” Lord Sankey asserting that a constitution was “a living tree capable of growth.”

The 1930s brought Rowell personal happiness, many plaudits, and new responsibilities. On 26 April 1930 his daughter, Mary, married Henry Rutherford Jackman*, a Conservative lawyer of Methodist background, whose character his future father-in-law had carefully investigated. His first grandchild, Henry Newton Rowell Jackman, a future lieutenant governor of Ontario, would be born three years later. In the spring of 1932 a group of clergy and laymen wished to nominate him as the first lay moderator of the United Church of Canada, an election he would stand an excellent chance of winning. The former president of Victoria University, Richard Pinch Bowles, who was a pacifist and a socialist, urged him to lead the church in the tumultuous times created by the Great Depression: he believed Rowell to be “a practical mystic” who understood the divisive social issues, enjoyed the esteem of both conservatives and Christian socialists, and respected those of differing opinions. Rowell declined to run, declaring that he had neither the energy nor the time to devote two years to the work. That year he was elected president of the Canadian Institute of International Affairs and of the Canadian Bar Association, and became an honorary bencher of Lincoln’s Inn, a greatly prized honour that had been conferred on only one other Canadian, Richard Bedford Bennett. Early in 1936 he enthusiastically accepted the task of defending the former prime minister’s New Deal legislation before the Supreme Court of Canada. King’s government was reluctant to implement measures that would require federal intervention in provincial areas of responsibility. Rowell favoured reforms that would have regulated business procedures and improved working conditions, and he was disappointed when most of the legislation was judged to be out of federal jurisdiction. He was to argue the appeal before the judicial committee.

In September, before he could leave for London, Rowell was offered the position of Chief Justice of Ontario, which he accepted after much deliberation. He was primarily engaged in cases of corporation law during his tenure, which had lasted for just under a year when King asked him to chair the royal commission on dominion-provincial relations. Its mandate was to examine the balance of powers and responsibilities between the federal and provincial governments. Among the commissioners were Rowell’s friend John Wesley Dafoe and notary Joseph Sirois. Rowell hesitated because he realized that he would have less time to give to his judiciary responsibilities and he had concerns about his health. After preparatory visits to provincial capitals in September and October, public hearings opened in Winnipeg on 29 Nov. 1937. As the commission moved through western Canada, the chairman displayed his vast knowledge and unfailing courtesy, winning the plaudits of critical journalists. The commission was in Toronto when, on 7 May 1938, Rowell suffered a heart attack, followed by a stroke that robbed him of speech. In November his resignations from the commission and from his position as chief justice were accepted, and Sirois took over as chairman. Rowell died three years later. The Rowell-Sirois report, as it is generally known, was completed in 1940. It had paid warm tribute to his intellect and character, recognizing his work in the commission’s preparation and early stages. There is no doubt that he would have approved the recommendations for minimum standards of education and social services for all Canadians, an outline for the development of the welfare state that would come into being after World War II.

At Rowell’s request there was no eulogy at his funeral at Metropolitan Church. His son, Frederick, wore the uniform of the Royal Canadian Air Force, a reminder that disarmament and the League of Nations had both failed. Most of the public comment was summarized by Bernard Keble Sandwell*, editor of Saturday Night (Toronto), under the heading “What Canada missed.” He asked why Rowell had not been permitted to play a larger role in the country’s development, and declared that neither his “austerity” nor his apparent disregard for party explained it. “A mature democracy does not reject great men for either of these reasons.”

Newton Wesley Rowell’s success as a politician was limited by his belief that if reasonable men discussed issues they would reach reasonable decisions. Methodist Arminianism may have been the origin of his naive hope that businessmen of his time could be persuaded that, if not from a sense of social justice, then in their own interest they should practise concern for their employees, and that dictators could be stopped by exhortation. However circumscribed his public impact, his personal reward was in doing what he believed to be right.

Documentation for this biography is found in Margaret Prang, N. W. Rowell, Ontario nationalist (Toronto and Buffalo, N.Y., 1975). The record of his marriage is at Arch. of Ont., RG 80-5-0-290, no.7642.

Newton Wesley Rowell is the author of The British empire and world peace: being the Burwash Memorial Lectures, delivered in Convocation Hall, University of Toronto, November, 1921 (Toronto, 1922); Canada, a nation: Canadian constitutional developments (Toronto, 1923); and “Canada and the empire, 1884-1921,” in The Cambridge history of the British empire, ed. J. H. Rose et al. (8v. in 9, Cambridge, Eng., 1929-59), 6: 704-37. Many of Rowell’s speeches have been made available in microform.

Cite This Article

Margaret E. Prang, “ROWELL, NEWTON WESLEY,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 17, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 1, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/rowell_newton_wesley_17E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/rowell_newton_wesley_17E.html |

| Author of Article: | Margaret E. Prang |

| Title of Article: | ROWELL, NEWTON WESLEY |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 17 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 2009 |

| Access Date: | April 1, 2025 |