Source: Link

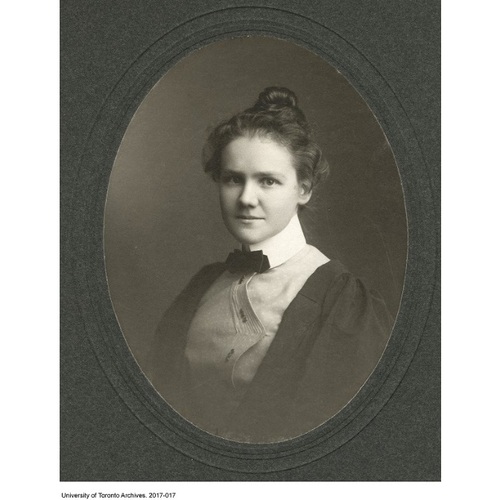

MACDONALD, ANNIE CAROLINE, missionary, social reformer, and interpreter; b. 15 Oct. 1874 in Wingham, Ont., fourth of the five children of Peter Macdonald, a medical doctor and future Liberal mp, and Margaret Ross; d. unmarried 18 July 1931 in London, Ont., and was buried in Wingham.

An independent Christian missionary in Japan – described by the people she served as “the white angel of Tokyo” – Caroline Macdonald belonged to a committed Presbyterian family. Her mother helped to establish the local branch of the Woman’s Foreign Missionary Society of the Presbyterian Church in Canada [see Marjory Laing*], and her father taught Sunday school and Bible classes. Macdonald was first educated at her local school. She then attended the collegiate institutes in Stratford, Owen Sound, and London, being influenced in the last two places by principal and science teacher Francis Walter Merchant. After proceeding to the University of Toronto, where she became active in the Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA) and the Student Volunteer Movement (SVM) for Foreign Missions, she graduated with honours in mathematics and physics in 1901.

She went on to work for the YWCA in London and in Ottawa, and briefly for the SVM, before becoming the YWCA’s national city secretary in February 1903. In late 1904, at the behest of the World’s YWCA and the national organization, she went to Japan to help establish the association there. She would spend all of her subsequent career in this country, where Protestant missionaries from Canada had been active for some time [see George Cochran*; Charles Samuel Eby*].

Once in Japan, Macdonald undertook an intensive six-month apprenticeship in the language, which she followed up with regular classes and another four months of concentrated study in 1911–12. She quickly found that a sense of humour was essential (“If you are devoid of that virtue,” she would later counsel new arrivals, “take the next boat out of Yokohama.”) Early in her career she was instrumental in developing the YWCA not only in Tokyo but also in Yokohama and ōsaka, creating summer camps, Sunday schools, and residences to provide safe accommodation for female students and single working women. She served as national secretary of the Japan YWCA until 1915. From 1905 to 1923 she taught English literature and Bible studies at what would become known as Tsuda College in Tokyo, a private Christian girls’ school founded by the celebrated women’s education pioneer Tsuda Umeko. In her work with the YWCA, Macdonald was greatly helped by her friend and fellow teacher at the college Emma Ratz Kaufman (daughter of Jacob Kaufman*), who arrived from Canada as a YWCA worker in 1911.

In Tokyo, Macdonald was associated with the Fujimichō Church, a Presbyterian congregation whose minister was Uemura Masahisa, one of the great figures in the history of Japanese Protestantism. Her membership in this body and her ties to Uemura helped to introduce her to many leaders in the Japanese Christian movement, including the labour activist Suzuki Bunji and the educator and politician Tagawa Daikichirō. Among her other famous Japanese Christian friends were Nitobe Inazō, the Quaker interpreter of Japan to the west, the evangelist Kagawa Toyohiko, and Kawai Michi, another champion of female education.

Macdonald had been raised in the Social Gospel tradition and this upbringing would find an outlet in her concern for prison reform as well as in her support for the labour movement. Although she was not the first missionary to become interested in penal work in Japan – Arthur Lea, a Canadian Anglican missionary, had pioneered prisoner rehabilitation in Gifu during the early 1900s – her activities and those of other women missionaries attracted much publicity. Macdonald first became involved in prison visiting in 1913 as a result of the trial of Yamada Zen’ichi, a Red Cross worker and member of her Sunday-evening Bible class who, in a fit of jealous rage, had murdered his wife and their two small sons. During her visits to Yamada in Tokyo’s Kosuge Prison, she befriended Arima Shirosuke, the jail’s Christian governor. Arima, a sometimes-controversial advocate of penal reform, became a key supporter of Macdonald in her prison activities and later at the settlement house that she established. Yamada, sentenced to life imprisonment, would be released in 1925 and would join Macdonald in her rehabilitation efforts.

Macdonald’s experience with Yamada persuaded her to change her focus to prison work. She resigned from the YWCA, and afterwards relied on her teaching and on donations for financial support. In early 1916 she met Ishii Tōkichi, a repeat offender. While in prison on a minor charge, he had confessed to murder on learning that an innocent man had been condemned for a crime that he himself had committed. During the course of his trial, he became a Christian. Before his execution in the summer of 1918, he was able to write, with Macdonald’s help, a simple and touching account of his life in which he stressed that he had been changed through the power of Jesus Christ. By the end of 1918 this account had been published in Tokyo, and ultimately Macdonald would translate it into English and organize its publication in the United States as A gentleman in prison.

In 1923 Macdonald’s social-welfare work – in addition to prisoners, she was particularly interested in factory girls and women – took concrete form in the establishment of a long-planned settlement house, Shinrinkan, whose inception was hastened by the earthquake that devastated Tokyo that year. This institution provided a wide range of services for the unemployed and the displaced; in addition, it offered night schools for workers, women’s knitting classes, English lessons, activities to engage delinquent children, training sessions for social workers, Bible-study classes, and group discussions of social issues. A second house, a centre for her prison endeavours, was opened in 1930. Not only did Macdonald visit the incarcerated, but she also strove to facilitate their re-entry into society and involved herself with their families; the centre served to support these efforts. Her concern for the problems faced by ex-prisoners and factory hands had led her to participate in the trade-union movement, and from the early 1920s labour questions consumed more of her time. In 1927, for example, she spoke to workers striking against the powerful Kikkoman soy sauce manufacturer, encouraging them to stand firm. Two years later she acted as interpreter for Matsuoka Komakichi and other Japanese delegates to the International Labour Organization conference in Geneva.

At some point Macdonald had been elected an elder of her Tokyo church, a rare distinction for a foreigner, and her educational and social work were recognized by emperors Yoshihito and Hirohito. The western community in Tokyo showed its respect by choosing her as a councillor of the Asiatic Society of Japan. In 1925 the University of Toronto conferred an honorary doctorate, making her the first woman to receive the lld degree there. She was, she said, “rather knocked out” by this accolade, believing that she had “never done anything for the Univ. of Toronto except get out of it as soon as possible, & keep away from it ever since.” These honours, her fund-raising activities in North America on behalf of her settlement house, her attendance at conferences in Europe, and particularly the publication of A gentleman in prison had made her a household name among Protestants in Canada and elsewhere in the west by the late 1920s.

Obliged to return home because of ill health in 1931, she died of lung cancer in London shortly afterwards. Like her contemporary Loretta Leonard Shaw, she had been concerned to represent her adopted country and its people to Canadians and others. Her gravestone is inscribed simply “Caroline Macdonald of Japan 1874–1931.” She was deeply mourned in Tokyo, where 1,000 people attended her memorial service. At a service in Toronto in September, lawyer Newton Wesley Rowell*, who had visited Macdonald’s establishments in Japan, extolled her “broad vision,” saying, “She worked toward a better understanding between races, seeking to bridge the gulf between the Occident and the Orient, believing that all races are children of a common Father, and that there should be a common feeling among them all.” As she had commented in the last year of her life, “Any fool can see the differences. It takes a loving heart and a well balanced head to see that we are all one.”

Annie Caroline Macdonald is the author of The woman movement in Japan (n.p., n.d.) and of a number of pamphlets, including The prisons of Tokyo and a social service opportunity ([Toronto?, 1920?]). She also contributed articles to periodicals such as the Women’s International Quarterly (London) and to the Japan Christian year-book (Tokyo). Her translation of Ishii Tōkichi’s memoir appeared in New York in 1922 as A gentleman in prison: with the confessions of Tokichi Ishii written in Tokyo Prison. Her papers at UCC, fonds no.3289, form the basis of Margaret Prang’s A heart at leisure from itself: Caroline Macdonald of Japan (Vancouver, 1995).

Globe, 28 Sept. 1931: 12. Endō Koichi, Tagawa Daikichirō to sono jidai [Tagawa Daikichirō and his times] (Tokyo, 2004). John McNab, The white angel of Tokyo: Miss Caroline Macdonald, ll.d. ([Toronto?, 1945?]). Nihon Kirisutokyō rekishi daijiten [A dictionary of the history of Christianity in Japan] (Tokyo, 1988).

Cite This Article

Hamish Ion, “MACDONALD, ANNIE CAROLINE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 31, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/macdonald_annie_caroline_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/macdonald_annie_caroline_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Hamish Ion |

| Title of Article: | MACDONALD, ANNIE CAROLINE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2023 |

| Year of revision: | 2023 |

| Access Date: | December 31, 2025 |