Source: Link

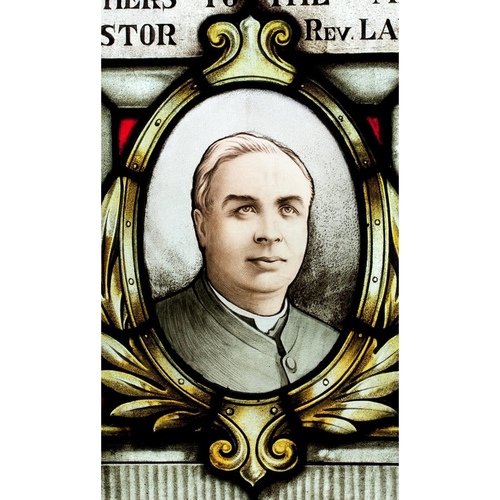

MINEHAN, LANCELOT (Launcelot) PETER, Roman Catholic priest and social reformer; b. 18 Jan. 1862 in Killaloe (Republic of Ireland), son of Michael Minehan and Hanna Skehan; d. 30 Dec. 1930 in Toronto.

Lancelot Minehan attended All Hallows College in Dublin, where he received the tonsure and minor orders on 10 June 1881. An accident forced him to return to Killaloe and resume his education under the guidance of F. J. McRedmond, the parish priest and vicar general. When he left for Canada in April 1884, McRedmond informed his sponsor, Archbishop John Joseph Lynch* of Toronto, that the young man “has always been as pious and gentle as he is industrious and intelligent. I have no hesitation in forecasting that you will find him in every way an Excellent priest.” Minehan would fulfil this prediction and become one of the most successful of the last generation of Irish-born missionary clergy to serve the archdiocese.

In Canada he continued his studies at Lynch’s summer home and the Grand Séminaire de Montréal. He was ordained on 20 December and appointed to St Luke’s parish in Thornhill, Ont. Barely acclimatized, he threw himself into his work. During his first eight years he was a curate in Thornhill, Brockton (Toronto), Adjala, and Toronto, and a chaplain at the Ontario Reformatory for Boys in Penetanguishene and the Central Prison in Toronto. He worked in Adjala for the flamboyant Father Francis McSpiritt*, who would have demonstrated the power of Irish clergy over their parishioners and the need for mutual loyalty. In 1896, after three years as pastor in Schomberg, Minehan was moved to St Peter’s mission church in Toronto, which he organized as a parish with a separate school, a new church, and a rectory. The single blemish on his record appeared in 1903, when he rallied parishioners over Archbishop Denis O’Connor*’s refusal to pay an assistant’s salary to his brother, Father James Minehan. Apostolic delegate Donato Sbarretti y Tazza settled the matter, scolding the brothers but instructing O’Connor to pay. Minehan’s final posting, in 1914, was to the city’s Parkdale area, where he built St Vincent de Paul into a powerhouse of Catholic life, despite wartime impediments. Between the laying of the cornerstone for a church in 1915 and its dedication in 1924, he had a rectory and a school constructed.

Despite his successes, Minehan was never fully satisfied with parochial duty. A forceful preacher, he had discovered early that he was equally at ease as a public speaker and that the press provided an excellent forum in an era when clerics spoke out on social or moral matters. In 1909 the Globe claimed Minehan’s “priesthood did not cancel his citizenship.” He later remarked, “I have never discussed politics from the pulpit, but believe it was my right to do so from the public platform, where all could hear and reply to me.” In his many contributions to local newspapers, including the Catholic Register, he never shied away from controversy; always courteous, he could be devastatingly blunt and occasionally sarcastic as he defended Catholic teachings. During the Protestant reaction in 1911 to the Ne Temere decree on matrimonial law, he delivered a “red-hot sermon” in which, the Toronto Daily Star reported, he accused critics of “ignorant and brutal outbursts of bigotry that are a disgrace, not alone to Christianity whose name they usurp, but to humanity itself.” To the claim of the Methodist Christian Guardian that Catholics in mixed marriages had been commanded to break their vows and abandon their spouses, he replied that such attacks were wilfully or stupidly unjust. He usually left the politically charged separate-school issue to the bishops [see Fergus Patrick McEvay*], but the dispute over the qualifications of some teaching nuns and brothers had prompted him in 1906 to write (and thus court unpopularity) that they should have obtained proper certificates in the first place. He further pointed out that separate schools had difficulty attracting qualified teachers because the government denied these schools their fair share of taxes. He later wrote a brilliant critique of Ontario’s legislation on taxes.

Minehan was more than an apologist. With a broad range of interests, he fashioned positions as a friend of the poor, a defender of both capital and workers’ rights (but an ardent foe of Bolshevism), and a promoter of causes, among them the reform of the civil service and the militia department, wartime conscription, Victory Loans, a Canadian navy, women’s suffrage, and Home Rule for Ireland. He supported the formation of the United Church of Canada in 1925 because he believed that, since it would contain most of the country’s Protestants, it could facilitate the teaching of religion in public schools. His beliefs carried him into several organizations: he was a vice-president of the Moral and Social Reform Council, a founder of the Parkdale Ratepayers’ and Progressive Businessmen’s Association and the Neighbourhood Workers’ Association, and a director of the Social Service Council of Ontario and the Penny Bank of Ontario, which encouraged thrift among the young. He introduced the first parish-based troop of Boy Scouts in the archdiocese and, alongside his parishioners, worked a plot of land on Yonge Street as an example of urban self-reliance. Minehan’s social concerns drew him toward the Social Gospel movement, but with reservation. He found nothing in Salem Goldworth Bland*’s The new Christianity . . . (Toronto, 1920), for instance, that had not already been voiced by Pope Leo XIII in the 1890s or by the American bishops in their pastoral letter of 1919.

Central to Minehan’s role as a reformer was his prominence in the temperance movement. As a parish priest, he would have dealt with families ruined by alcoholism, but he was realistic enough to know that Prohibition would never prevail in a society where alcohol had always been present. The legacy of hotels with bar rooms had to be tolerated, he believed, but neighbourhood bars with no tradition behind them should be abolished; he worked to reduce with compensation the number of licensed establishments. A vice-president of the Ontario branch of the Dominion Alliance for the Total Suppression of the Liquor Traffic, he joined the wildly popular ban-the-bar movement led by Newton Wesley Rowell*, who became leader of the provincial Liberals in 1911. Minehan’s greatest moment in the cause came on 25 June 1914, four days before a provincial election, when he chaired a major rally at Massey Music Hall in Toronto. During his emotional speech to a mainly Protestant audience, he claimed Catholics had suffered the most from the bar-room curse and scathingly referred to Catholic liquor merchants as knifers. The Conservatives retained power, but the campaign for Prohibition found new impetus during the war; in 1916 the government passed the Ontario Temperance Act. When the Conservatives moved to abandon it in 1927 in favour of government control, Minehan re-entered the fray.

The temperance movement had brought him into contact with many of Toronto’s leading Protestant clergymen. Theological differences aside, and as long as the Orange lodge was not involved, they worked well together, a relationship that may help explain Minehan’s ecumenical spirit. He defended the appointment of Anglican archdeacon Henry John Cody* as minister of education in 1918, he spoke in 1923 at West Presbyterian Church on the “ideals of citizenship” (an address praised by the Globe as “another body blow to old prejudices”), and in 1927 he offered the basement of his church to the congregation of Erskine United when it burned.

Lancelot Minehan died unexpectedly of a stroke three years later. Known and respected for his toleration and charity, he was described by Edwin Austin Hardy* of the Community Welfare Council of Ontario “as a man of lovable personality, of strong convictions and of the most devoted zeal in the service of his Lord and Master.”

Lancelot Peter Minehan delivered an address entitled “Civil service reform” to the Empire Club of Canada on 8 Nov. 1906 (Empire Club of Canada, Speeches (Toronto), 1906–7: 71–76).

Arch. of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Toronto, Clergy biog. and ministry database; Clergy personnel records fonds, Lancelot Minehan file; Rev. E. J. Kelly clergy journals, Minehan entry; L (Lynch papers), AA05.2047; LB (letterbooks), 01.319; ODS (O’Connor – apostolic delegate papers), 05.07, 10, 23, 25(b); 07.10, 13, 21. Catholic Register (Toronto), 1906–7, 1917, 1931. Christian Guardian, 1911. Evening Telegram (Toronto), 1910, 1919, 1924, 1929, 1931. Globe, 1909–10, 1914, 1918–20, 1923–24, 1930. News (Toronto), 3 Nov. 1906. Toronto Daily Star, 1911, 1915–20, 1922–23, 1925, 1927, 1930. Richard Allen, The social passion: religion and social reform in Canada, 1914–28 (Toronto, 1971; repr. 1990). Canadian annual rev., 1907: 471; 1908: 317–18; 1910: 178; 1911: 326; 1912: 351; 1913: 736; 1914: 445; 1917: 412; 1918: 608; 1919: 237–38. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1912). Kevin Condon, The Missionary College of All Hallows, 1842–1891 (Dublin, 1986). M. G. McGowan, The waning of the green: Catholics, the Irish, and identity in Toronto, 1887–1922 (Montreal and Kingston, Ont., 1999). J. S. Moir, “Canadian Protestant reaction to the Ne Temere decree,” CCHA, Study Sessions, 48 (1981): 78–90. St. Vincent de Paul parish: golden jubilee, 1915–1965 ([Toronto, 1965]).

Cite This Article

Michael Power, “MINEHAN, LANCELOT (Launcelot) PETER,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 23, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/minehan_lancelot_peter_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/minehan_lancelot_peter_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | Michael Power |

| Title of Article: | MINEHAN, LANCELOT (Launcelot) PETER |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2005 |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | December 23, 2025 |