Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

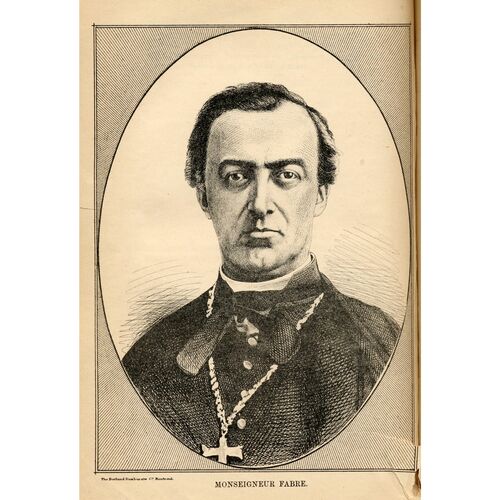

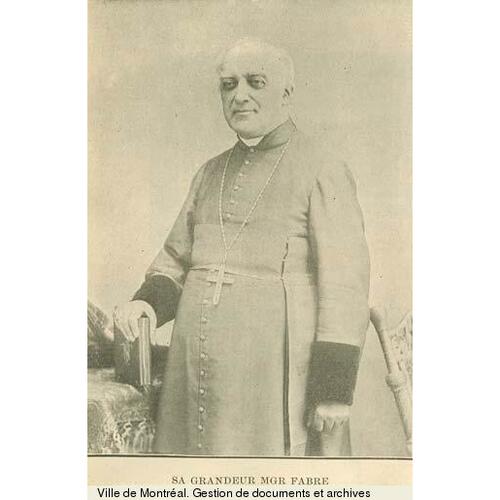

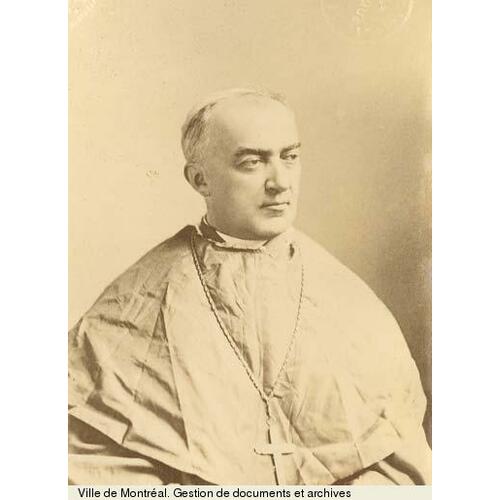

FABRE, ÉDOUARD-CHARLES, Roman Catholic priest and archbishop; b. 28 Feb. 1827 in Montreal, eldest son of Édouard-Raymond Fabre* and Luce Perrault; d. there 30 Dec. 1896.

Édouard-Charles Fabre was born into two families that had only recently acceded to the bourgeoisie from the artisan community. His maternal grandfather had risen from master baker to agent for the Montreal–Quebec stage line, and among his uncles were a bookseller and important printer, Louis Perrault*, a lawyer and member of the Lower Canadian House of Assembly, Charles-Ovide Perrault, and a doctor, Joseph-Adolphe Perrault. His paternal grandfather had been a carpenter, and his father had advanced from clerk in a hardware store to proprietor of a bookstore by 1823. Thereafter the elder Fabre invested successfully in printing, retailing, finance, and newspapers.

Fabre’s father and maternal uncles were prominent supporters of the Patriote party, led by Louis-Joseph Papineau*. Indeed Charles-Ovide Perrault and Édouard-Raymond Fabre fought at the battle of Saint-Denis, on the Richelieu, in 1837; the former was killed there and the latter was imprisoned in 1838. While the males of Édouard-Charles’s family were prominent in liberal politics, the female Perraults established reputations in Roman Catholic philanthropy; Luce participated with her mother and a sister in the Association des Dames de la Charité and, later, in the Montreal Asylum for Aged and Infirm Women and in the Asile de la Providence.

Luce, married at 15 and giving birth 9½ months later to Édouard-Charles, the first of 11 children, managed a household that included four servants. In her domestic, maternal, and philanthropic activities, she provided the family setting, the image, and the support expected from a woman of her class. Her husband described her as “the gentlest, the most charitable, the least pretentious” of women. Even after Édouard-Charles was sent for his classical studies to the Séminaire de Saint-Hyacinthe at age nine in 1836, he remained close to his mother; intimacy and affection permeate his letters to her. Luce Perrault was to survive her husband by 56 years. As an adult and priest, Édouard-Charles would work with her to maintain the image of the family despite the death of its head, deep ideological differences between him and his siblings, and the breakdown of his sister Hortense’s marriage with George-Étienne Cartier*.

Édouard-Charles’s relations with his father were more enigmatic. Family life was a priority for the elder Fabre, who owned an impressive home and embellished his private world with a piano and other signs of material comfort. His business and political status ensured his son a childhood in the comfortable bourgeois milieu of the Cuvilliers, the Papineaus, and the Cherriers. A man of little formal education himself, he was prepared to invest heavily in the education of his children in order to secure their social advancement, and his prominence obtained privileged treatment for Édouard-Charles at the seminary. He was displeased when he learned that his son was leaning towards the priesthood, a vocation not favoured among those of Fabre’s class and political views.

When Édouard-Charles finished his studies at Saint-Hyacinthe in 1843, he accompanied his father on a business trip to Paris and then stayed there for a year with his father’s sister, Julie. Her husband, Hector Bossange, was Fabre’s Paris partner and supplier of books. Although considering his son “a good child” and “wise and reserved,” Fabre found him “too apathetic” and wished him “more ambitious.” He hoped that in Paris his son would see something of the world. However, Édouard-Charles was soon disgusted and alienated by secular life in Paris. His inclination towards the priesthood reasserted itself at the Sulpician seminary in Issy-les-Moulineaux, where he began to study philosophy in 1844. Fabre attempted to counter his son’s preference, but Édouard-Charles was decided and, with his mother’s support, he won his father’s grudging acceptance. “Let him be,” Fabre wrote to the Bossanges, “since he absolutely will be a priest, the poor child will be happier, I think, than he would be in the world.” To his son he wrote: “If you are going to be a priest, you must be a very distinguished priest.” On 17 May 1845 Édouard-Charles was tonsured in Paris. He finished his studies at Issy-les-Moulineaux in February 1846 and, after a visit to Rome and an audience with Pope Pius IX, returned to Montreal.

In September 1846 a heartbroken Fabre wrote to Julie Bossange, “My poor abbé has left the paternal home forever.” Through Fabre’s influence Édouard-Charles undertook his theological studies in the episcopal palace under the direction of Bishop Ignace Bourget* rather than in the Séminaire de Saint-Sulpice, the main theological college in Montreal. While a theology student Édouard-Charles gave Sunday catechism, directed a choir, and prepared 75 Irish orphans for first communion. On 23 Feb. 1850 he was ordained in the cathedral of Saint-Jacques in Montreal, and later in the year he was named assistant priest at Sorel. In 1852 he became parish priest of Pointe-Claire. His letters to his father, now a prominent liberal politician and journalist, became more authoritarian and he severely criticized Le Pays (Montreal), a liberal newspaper his father had helped found; on one occasion he described it as “a veritable scandal for my parish.”

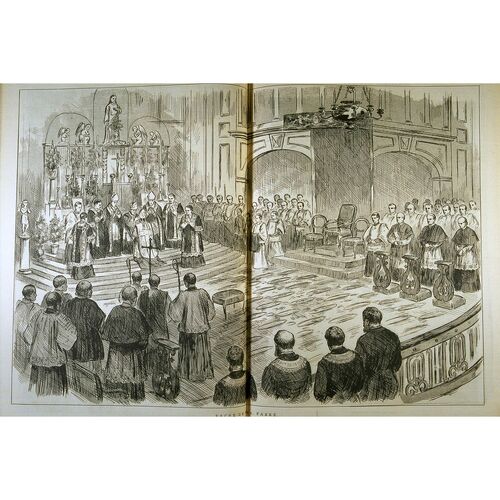

Young Fabre’s ascension as a protégé of Bourget was signalled in 1856 by his nomination as a canon of the cathedral. In this position he was, according to a contemporary, Laurent-Olivier David*, “the priest à la mode, the one to whom people went on critical or on solemn occasions, whom they sought out for fashionable marriages.” Since his student days, Fabre had nourished a passion for church liturgy, and over his lifetime he developed an international reputation for it.

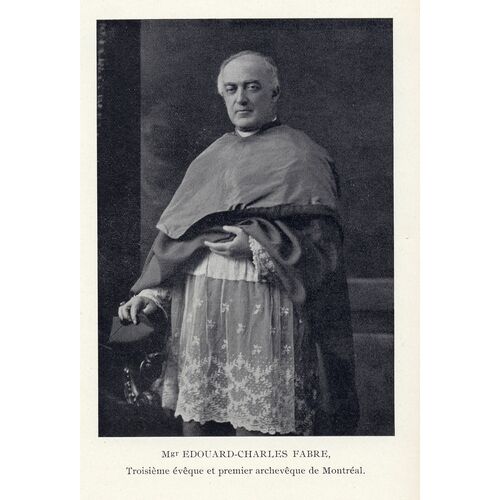

In 1873 Bourget requested and received Fabre as coadjutor with the right of succession. For years Bourget had been battling with successive archbishops and with the clergy at Quebec. Tired of acting as an arbiter in these differences over power, religious ideology, and personality, Rome urged both sides to cease their unbecoming hostilities and, in a gesture of reconciliation, Archbishop Elzéar-Alexandre Taschereau himself consecrated Fabre bishop of Gratianopolis on 1 May 1873. Nevertheless, the archbishop’s entourage was not enchanted with Bourget’s choice. “This will not be the brightest of bishops, nor the most capable of putting the so-called Gallicans in their place,” wrote Antoine-Narcisse Bellemare, professor of philosophy at the Séminaire de Nicolet. In the diocese of Montreal, however, the choice was “greeted with joy” according to David. Contrary to Bellemare, David credited Fabre with a quick mind and a remarkable memory. Jovial in personality and paunchy, Fabre was, by his own account, slow to anger. David concluded that the young bishop’s “strong brow and bald head will bear the mitre well.” Bourget continued to do battle with Quebec until, following a particularly disappointing reverse over the establishment of a Catholic university in Montreal, he retired. On 11 May 1876 Édouard-Charles Fabre became the third bishop of Montreal.

The new bishop inherited from his predecessor a diocese that was well structured and comfortably supplied with priests but embroiled in politico-religious conflicts and nearly buried in debt. By 1879 the interest charges on the debt of $750,000 had reached more than $50,000 a year. As well, with a prodigious influx into the city of job-seeking rural inhabitants, the establishment of new working-class parishes such as Saint-Louis-de-France (1880), Saint-Charles (1883), St Anthony of Padua (1884), Saint-Léonard (1885), Immaculée-Conception (1887), Très-Saint-Nom-de-Jésus (1888), Sainte-Élisabeth-du-Portugal (1894), and Présentation-de-la-Sainte-Vierge in Dorval (1895) entailed additional capital expenditures. To reduce the debt Fabre took a number of energetic measures, including suspension from 1879 to 1885 of the construction of Bourget’s beloved new cathedral of Saint-Jacques and imposition of onerous financial responsibilities on the parishes. All Catholics were asked or obliged to contribute in one form or another. He introduced a special levy on every Catholic in the archdiocese of one cent a month for two years (1889), renewed an annual tithe of a minimum of $2 for families and $1 for individuals living apart from their families, instituted a $100 levy on religious communities (1895), increased the price of special masses, announced an indulgence of 40 days to those who helped alleviate the diocesan deficit (1887), solicited a public loan of $70,000 to finish the cathedral roof (1885), asked the pope for permission to sell certain properties (1880) and subsequently sold several (1882–83), and installed a 25 per cent levy on funeral fees collected by parish priests or fabriques (1895).

Despite the dramatic crisis evident in the expanding working-class population in his diocese, Fabre was a strong opponent of fundamental social change. In keeping with late 19th-century Catholic social doctrine, he resisted an interpretation of Quebec society based on a struggle between capital and labour. Holding corporatist views, he emphasized the importance of work, cooperation, and obedience on the part of the workers and he rejected labour’s use of the strike to protect skills and status; in 1882 he ordered priests to denounce a shoemakers’ strike from the pulpit. Labour should organize only under the patronage of employers and the church, he argued. Perceiving the Knights of Labor as a particular danger, he supported their condemnation by Taschereau and declared membership in the organization a mortal sin.

Fabre was concerned at the moral consequences of poverty and deeply preoccupied with the threat posed by an increasingly mobile and urban society. Thus he opposed dime theatres, lotteries, amusement parks, picnics, carnivals, baby contests, dancing by young people, the presence of girls at public gatherings, and Sunday concerts and bazaars. He presided over temperance meetings, called for the rejection of liquor licences in local option votes, campaigned against sledding and snowshoeing, condemned the wearing of jewellery by women, banned mixed choirs, and, except for special occasions, denied women permission to sing in church. His strong fear of promiscuity led him to prohibit mixed pilgrimages if they entailed overnight travel on trains or boats. To strengthen the soul against social evils, Fabre placed great emphasis on retreats, organizing them for particular social groups such as the liberal professions and shopkeepers. As well, inspired by Pope Leo XIII’s campaign to reinforce Christianity in the family, Fabre established the Association Universelle de la Sainte-Famille in 1892. Here he drew on the model of the holy family to outline gender roles in a Christian family: Joseph was the just head of the family, Mary the gracious mother, and Jesus the dutiful son.

To minister to his growing diocese Fabre inherited from Bourget a numerous secular clergy and a considerable number of religious communities. Over 23 years he maintained the church’s labour force by ordaining 210 priests for work in the diocese and by accepting or introducing at least 10 religious communities, including the Trappists, the Franciscans, the Brothers of Christian Instruction, and the Petites Sœurs des Pauvres; as well, some 4,200 men and women took vows or the habit. Fabre ordained many more priests to exercise their ministry outside the diocese and even outside the country as a heightening of religious sentiment intensified missionary zeal. Fabre himself travelled extensively in his diocese; over the course of his episcopate he made 1,284 visits to parishes, confirming 222,438 persons. A strong supporter of the colonization movement and of the Société de Colonisation du Diocèse de Montréal, founded by parish priest François-Xavier-Antoine Labelle in 1879, Fabre visited a different parish each year to celebrate the feast of St Isidore, the patron saint of colonization.

The diocesan debt adversely affected Fabre’s relations with some of his clergy. Financial restraints made him reluctant to accept responsibility for the introduction of new religious communities while, in his view, too many priests, his infantry in the battle to stabilize the diocesan debt, were financially irresponsible or unresponsive. He ordered his priests to obtain diocesan approval before borrowing for parish projects and, wherever possible, to take control of parish finances from the church wardens. For their part, many priests disliked having to shoulder part of the diocesan financial burden and resented his interference in parish finances. Fabre opposed the involvement of priests in public administration or in private companies. Dubious about their role on the boards of directors of railways, he forbad them to invest in banks, newspapers, or manufacturing enterprises. He was particularly opposed to the participation of Labelle in Honoré Mercier’s administration as assistant commissioner in the Department of Agriculture and Colonization. He maintained this opposition even after Labelle and Mercier appealed successfully over his head to Rome. The moral qualities of his clergy were another source of conflict. Fabre tightened control over clerical dress codes, prohibited beards (1882), and rooted out priests who drank. Nuns were to obey their community’s rules without question and were to avoid all behaviour that might lead to scandal. To protect their chastity, they were never to be alone with a male, be he layman or priest. As a means of reinforcing the clerical vocation, Fabre emphasized retreats; in 1887, for example, he presided over a retreat in which 200 priests participated.

In at least one regard his relations with the clergy were better than those of Bourget. Division of the parish of Montreal had been achieved by 1876, thus lancing the longstanding boil of the conflict between Bourget and the Sulpicians, who had tenaciously defended their titular rights over the parish of Montreal. Fabre periodically scuffled with the Sulpicians over liturgy or jurisdiction but on the whole his relations with Montreal’s most powerful religious community were serene. Significantly he stayed for three months in the Sulpicians’ Canadian College during a visit to Rome in 1890.

Fabre was also able to defuse the long struggle between his diocese and the archbishopric of Quebec. In 1877, the year after Fabre’s consecration, Rome sent Bishop George Conroy* as apostolic delegate to resolve the division among the clergy over political and theological issues. Fabre cooperated fully, abandoning the extreme ultramontane positions of Bourget that had constituted a principal source of conflict with Archbishop Taschereau. Having apprenticed with Bourget for nearly 30 years, Fabre was unquestionably a strong ultramontane notwithstanding the liberal politics of his father, his own tendency to seek compromise, and his preference for liturgy over politics. His first pastoral letter as bishop, emphasizing the danger to which the church was exposed by the indifference of the faithful and by the hostility of secular, impious, and liberal forces, constituted a strong affirmation of ultramontane views. However, unlike the extreme ultramontanes, who refused any compromise over what they considered to be the rights of the church, Fabre shared Taschereau’s realistic approach to society, the view that nothing human can be perfect and that one must deal with men as they are.

In politics, for example, Fabre accepted the position of Conroy and Taschereau that the church must abandon rigid political platforms, such as the Programme catholique [see François-Xavier-Anselme Trudel*] which Bourget had supported and which had condemned all forms of liberalism. He further opposed the ultramontanes in January 1877 when he joined Taschereau and Bishop Antoine Racine of Sherbrooke in resisting their pressure to reproach judge Louis-Napoléon Casault, who had condemned the priests of Bonaventure riding for exercising undue political influence in the provincial elections of 1875. In September 1878 the extreme ultramontane priest Luc Desilets* placed Fabre on a list of bishops who were too lenient towards liberalism. In 1880 Fabre presided at the funeral of Gonzalve Doutre*, a prominent liberal and former president of the Institut Canadien. On the other hand, in 1891, Fabre refused a request by Liberals to transfer to consecrated ground the remains of Jean-Olivier Chénier*, a Patriote who had been killed in 1837 at the battle of Saint-Eustache in armed resistance to what the church considered the divinely constituted authority of the state.

Fabre moved cautiously in his relations with political parties. As the radicalism of the Rouges moderated into a political liberalism which sought a modus vivendi with the church, Fabre softened the episcopal stance. In 1877, the very year that Wilfrid Laurier* embraced moderate liberalism, Fabre enjoined his priests not to accept political posts. They were to refrain from taking political sides in the pulpit, and opponents of the church were not to be refused the sacraments or accused of committing a sin. In fact, Fabre undoubtedly had a penchant for the Conservative party; during the elections of 1891 a pastoral letter that he published on the advice of the Conservative Louis-Olivier Taillon*, vaunting the benefits of the British connection to the French Canadians, scandalized the Liberals, who were advocating reciprocity with the United States.

Whatever the party in power, however, Fabre consistently supported the authority of the state. When popular resistance to vaccination became violent during a smallpox epidemic in 1885 [see Alphonse Barnabé Larocque de Rochbrune], Fabre ordered his priests to reassure their parishioners about the procedure and not to interfere with doctors who were vaccinating. Nationalist issues posed more dangerous political problems. Fabre named a chaplain for the 65th Battalion of Rifles (Mount Royal Rifles), which formed part of the expedition to quell Louis Riel*’s North-West rebellion of 1885, but later he admitted privately that he had underestimated the political significance of Riel. In the aftermath of Riel’s execution, Fabre tried to distance the church from the numerous demonstrations of protest. The Manitoba school question of the 1890s also proved embarrassing; in 1891 and again in 1896 bishops in Quebec tried to balance opposition to what they called laicization of Manitoba schools with what Fabre described as actions “which might appear to be partisan.”

Fabre was more forthright in dealing with the press. In 1882 he supported the establishment of a diocesan newspaper, La Semaine religieuse de Montréal, and in the same year he forbad Catholics to read or possess Le Courrier des Éats-Unis (New York) under penalty of “grievous error.” A decade later he condemned the radical Liberal newspaper the Canada-Revue (Montreal) and its Liberal confrère the Écho des Deux-Montagnes (Sainte-Scholastique), and instructed Catholics not to print, stock, sell, distribute, receive, or read them under pain of refusal of the sacraments. Both newspapers were obliged to cease publication, but they reappeared under other names and with a more moderate language. Aristide Filiatreault*, editor and publisher of the Canada-Revue, sued Fabre for damages but was unsuccessful. To control the influence of newspapers such as the radical liberal La Patrie and the ultramontane Le Monde (Montreal), Fabre proposed that a priest oversee their contents.

In reducing conflict with Archbishop Taschereau, Fabre sought above all to conform to Rome’s wishes. Doing so, however, he was often accused by extreme ultramontanes of weakness and of sacrificing to Quebec the interests of his diocese, which had always been closely identified with those positions of Bourget that Taschereau had successfully combated. Bourget had resigned, in fact, when Taschereau, through Benjamin Pâquet in Rome, had succeeded in 1876 in having the old bishop’s long-cherished dream of a diocesan university at Montreal rejected in favour of a Montreal campus of Université Laval. Fabre had hoped that Rome would not impose a branch university on Montreal because of the financial burden it would place on the diocese. When it was learned that Montreal would have to finance Laval’s monopoly of university education in the city, a decision already widely unpopular with the public became even more so. Still, Fabre told his people in 1878, “the Sovereign Pontiff . . . has decided that what was needed in Montreal was a branch of Université Laval. . . . I obey. . . . There is no longer a case once Rome has spoken.” Yet he attempted quietly to obtain an independent university during a visit to Rome in 1879–80; when he too failed, however, he abandoned that course. His acceptance of Rome’s decision aroused the intense opposition of influential individuals and institutions in his diocese. These included Bourget himself (supported by Bishop Louis-François Laflèche of Trois-Rivières), most of the canons of the cathedral (largely appointed by Bourget), and the ultramontanes Frédéric Houde* of Le Monde and François-Xavier-Anselme Trudel. Also strongly opposed were Dr Thomas-Edmond d’Odet d’Orsonnens and the Montreal School of Medicine and Surgery, which seemingly would have to make way for a branch faculty of medicine, and the Hôtel-Dieu, which was tied contractually to the school. On the other hand, as Fabre manœuvred to limit alienation within his diocese, Taschereau criticized him for not adequately imposing his authority to suppress opposition to Rome’s decision. For his part Fabre felt that Taschereau and the rector of Université Laval, Thomas-Étienne Hamel, complicated his task through their lack of discretion.

In 1883, with the university problem still a major source of conflict not only within the church but within Quebec society, Rome sent another apostolic delegate, Dom Joseph-Gauthier-Henri Smeulders, to find a formula that would regulate it within the framework of a branch campus. Fabre believed that he had the formula: Montreal must become an archdiocese and operate its campus with virtual autonomy from Quebec; the head of the branch, the vice-chancellor of Laval, must be the archbishop of Montreal, and the vice-rector must be from that archdiocese. Since at least 1879 Fabre had been promoting division of the archdiocese of Quebec; as he argued to the apostolic delegate, “Montreal accepts only with repugnance the yoke of its elder; its character is different; its activity is not directed to the same objects.” Taschereau, fearing conflicts between the two archdioceses and a reversal of the hard-won victory of Université Laval, opposed Montreal’s elevation. In 1886, however, the decision to raise Taschereau to the rank of cardinal removed his objections to the division of his archdiocese. On 8 June 1886 Leo XIII – who is reported to have said, “One must never disappoint Fabre, he is kindness itself” – named him archbishop of Montreal, and the following year the dioceses of Sherbrooke and Saint-Hyacinthe, under bishops Antoine Racine and Louis-Zéphirin Moreau*, were made suffragan to the new archdiocese.

Thenceforth Fabre doggedly pursued his plan for settling the university question. In February 1889 his efforts were rewarded by the bull Jamdudum, which made the Montreal branch largely autonomous of Laval. The archbishop of Montreal became vice-chancellor of Laval with a veto on the appointment or destitution of professors and deans on the Montreal campus; colleges affiliated with the Montreal branch could participate in developing certain programs, the Montreal School of Medicine and Surgery became the Faculty of Medicine, and the Jesuits, whom Fabre had supported, were given special status.

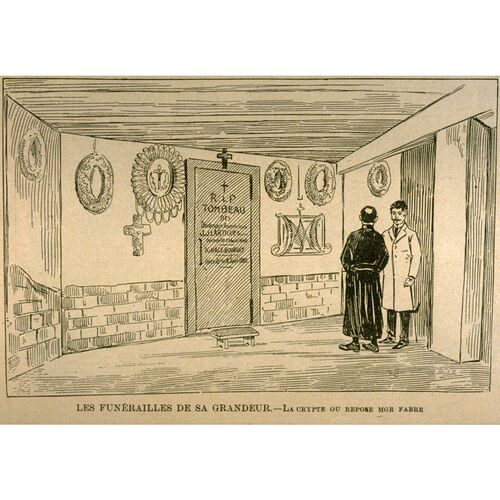

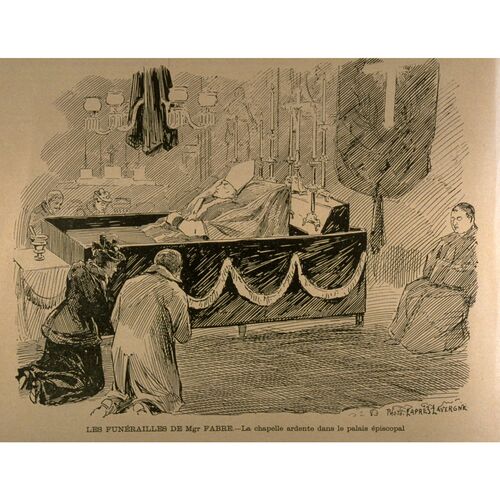

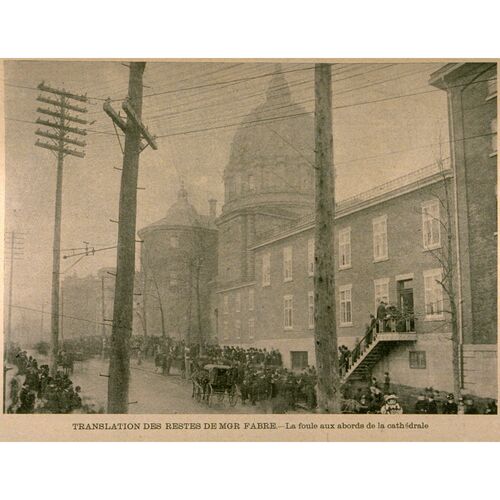

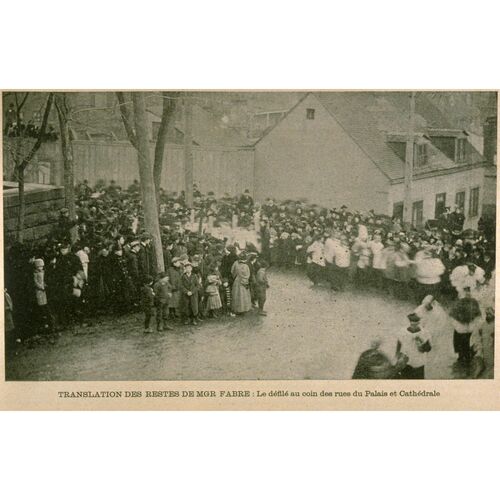

In the course of his episcopacy Fabre often travelled outside his diocese. In 1887, after completion of the Canadian Pacific Railway, he went in a special car to St Boniface, Man., for the consecration of Bishop Alexandre-Antonin Taché’s newly completed cathedral and then continued west to Victoria. He also visited Prince Edward Island, and outside the country he went to New England, Maryland, Britain, and France. He was in Rome several times and it was during a stay in the Eternal City in 1896 that he was found to have cancer of the liver. After returning to Montreal, he died “gently, without agony,” on 30 December. He was buried on 5 Jan. 1897 in the cathedral of Saint-Jacques. In respect for his dislike of funeral ostentation there were neither flowers nor speeches at the service, which was attended by, among others, the lieutenant governor, 5 archbishops, and 17 bishops. His material possessions having already been distributed to needy seminarians, Fabre left no will; 2,000 masses were said for the repose of his soul.

The 20 years during which Édouard-Charles Fabre was bishop and then archbishop of Montreal constitute, for religious historians such as Nadia Fahmy-Eid and Rolland Litalien, a period of growing power for the church in Quebec society. Fabre’s bourgeois origins among the most prominent Patriote elements and his passage to the ultramontane hierarchy underline the complexity of ideological currents and social structures in 19th-century Quebec. Distancing himself from the liberalism of his father on the one hand and the extreme ultramontanism of Bourget on the other, he sought an accommodation with moderate, pragmatic adherents to both poles of thought. At the same time he reinforced the puritanism and social conservatism that had characterized Bourget’s episcopacy. He strengthened the church’s control over the diverse social elements of his diocese – the popular classes, women, the clergy, the press, labour, and the liberal professions. He subordinated sexuality, popular culture, the spheres of women’s activities, and religious diversity to priorities of order, discipline, duty, strict liturgy, and male domination of the public and private worlds. He put diocesan finances back on a sound basis despite the construction of a huge cathedral and the opening of many new parishes. Finally, he did much to establish ecclesiastical peace by his central role in settling the university question and in the division of the archdiocese of Quebec. Although Fabre did not have the prominence of his predecessor, Bourget, or of his successor, Paul Bruchési*, his episcopacy is one of considerable significance for an understanding of the evolution of Quebec society in the final quarter of the 19th century.

[Peter Gossage, Christian Roy, and Lise St-Georges provided research assistance for this biography.

Photographs of Édouard-Charles Fabre are published in L.-O. David, Biographies et portraits (Montréal, 1876); Rolland Litalien, “Monseigneur Édouard-Charles Fabre, troisième évêque de Montréal (1876–1896),” Église de Montréal: aperçus d’hier et d’aujourd’hui, 1836–1986 ([Montréal, 1986]), 83–88; L’Opinion publique, 24 avril 1873; Gérard Parizeau, La chronique des Fabre (Montréal, 1978); and Léon Pouliot, Trois grands artisans du diocèse de Montréal (Montréal, 1936).The bishop’s palace in Montreal has a portrait of Fabre and the Musée de la Civilisation (Quebec) a bust. The principal sources for Fabre’s career are located at the ACAM and they are described in François Beaudin, “Inventaire d’archives: Archives de la chancellerie de l’archevêché de Montréal, instruments de recherche, 1877–1896,” RHAF, 24 (1970–71): 111–42; ACAM, dossier 902.004, is of particular interest. b.y.]

ANQ-M, P1000-7-561; P1000-17-669. ANQ-Q, P1000-37-693. ASSM, 27, tiroirs 103–4. Mandements, lettres pastorales, circulaires et autres documents publiés dans le diocèse de Montréal depuis son érection (23v., Montréal, 1869–1952), 9–12. La Semaine religieuse de Montréal (Montréal), 1 (1883)–30 (juill.–déc. 1897). Gabriel Dussault, Le curé Labelle; messianisme, utopie et colonisation au Québec, 1850–1900 (Montreal, 1983). Nadia Fahmy-Eid, Le clergé et le pouvoir politique au Québec: une analyse de l’idéologie ultramontaine au milieu du XIXe siècle (Montréal, 1978). Jean Hamelin et Nicole Gagnon, Histoire du catholicisme québécois: le XXe siècle (2v., Montréal, 1984), 1. René Hardy, Les Zouaves; une stratégie du clergé québécois au XIXe siècle (Montréal, 1980). Lavallée, Québec contre Montréal. Pouliot, Mgr Bourget et son temps. J.-L. Roy, “Édouard-Raymond Fabre, bourgeois patriote du Bas-Canada, 1799–1854” (thèse de phd, univ. McGill, Montréal, 1972); Édouard-Raymond Fabre, libraire et patriote canadien (1799–1854): contre l’isolement et la sujétion (Montréal, 1974). Robert Rumilly, Histoire de Montréal (5v., Montréal, 1970–74), 3; Mercier et son temps. Voisine, Louis-François Laflèche. Jean De Bonville, “La liberté de presse à la fin du XIXe siècle: le cas de Canada-Revue,” RHAF, 31 (1977–78): 501–23. Édouard Fabre Surveyer, “Édouard-Raymond Fabre d’après sa correspondance et ses contemporains,” RSC Trans., 3rd ser., 38 (1944), sect.i: 89–112. J.-L.Roy, “Livres et société bas-canadienne: croissance et expansion de la librairie Fabre (1816–1855),” Social Hist. (Ottawa), 5 (1972): 117–43.

Cite This Article

Brian Young, “FABRE, ÉDOUARD-CHARLES,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 4, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/fabre_edouard_charles_12E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/fabre_edouard_charles_12E.html |

| Author of Article: | Brian Young |

| Title of Article: | FABRE, ÉDOUARD-CHARLES |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1990 |

| Access Date: | April 4, 2025 |