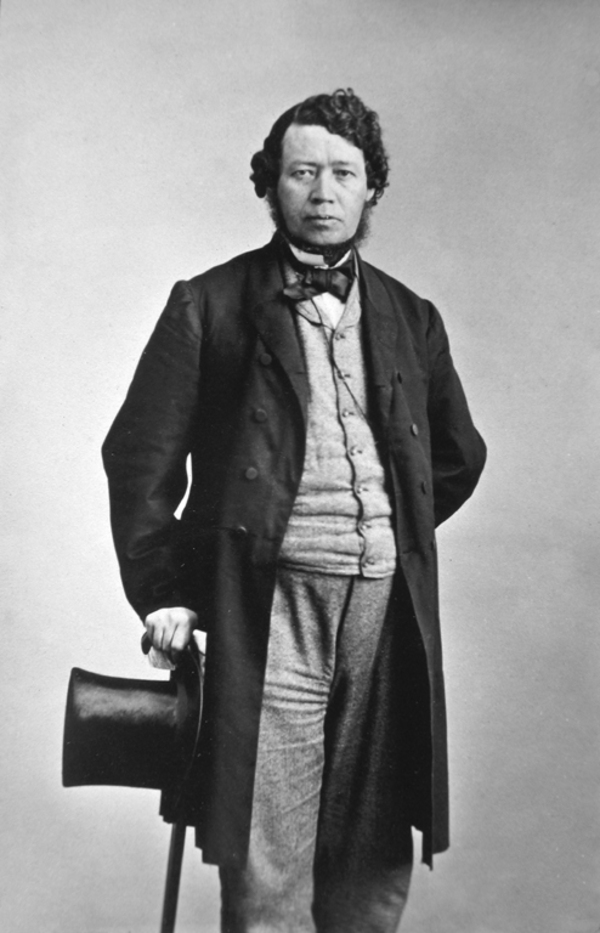

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

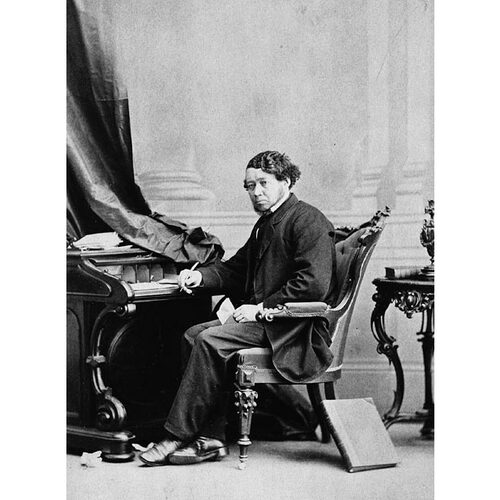

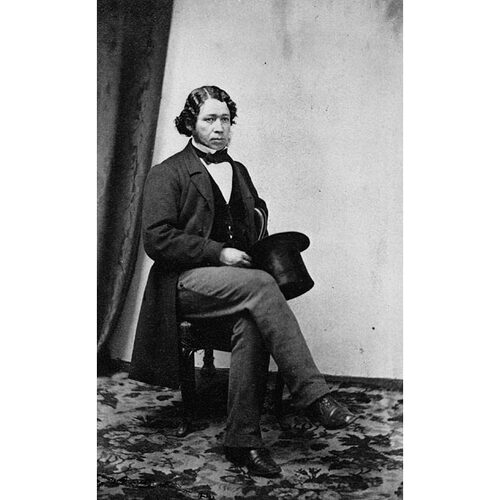

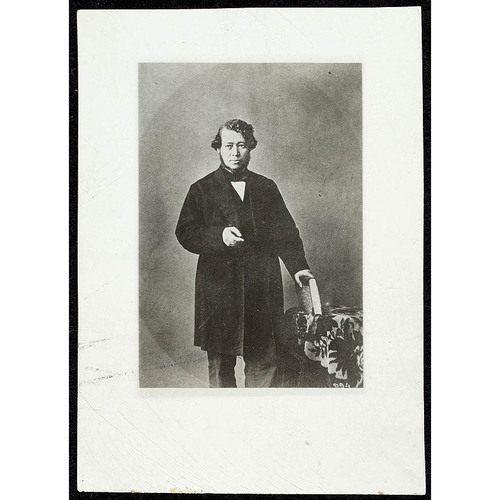

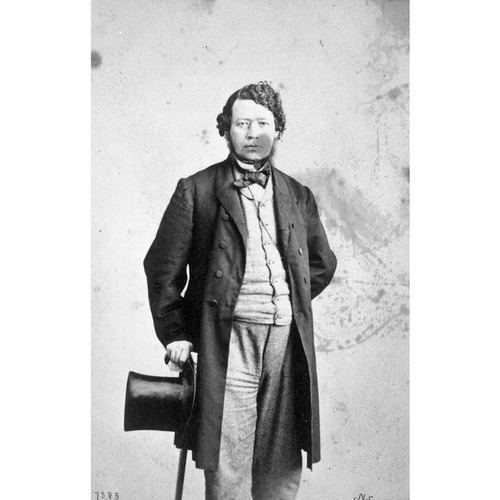

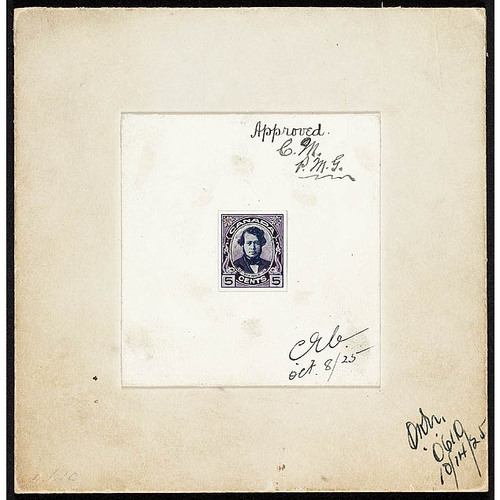

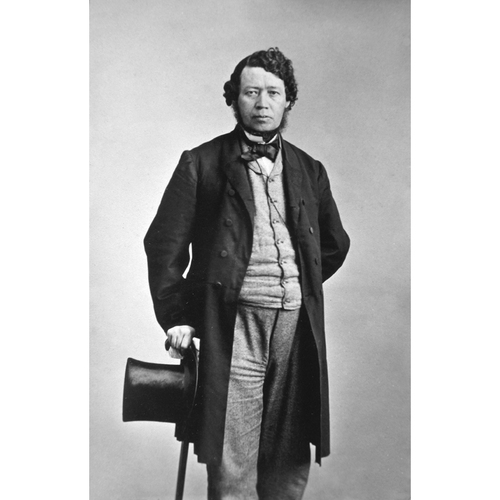

McGEE, THOMAS D’ARCY (he signed both McGee and M’Gee), journalist, poet, and politician; b. 13 April 1825 in Carlingford, County Louth (Republic of Ireland), fifth child of James McGee and Dorcas Catherine Morgan; assassinated 7 April 1868 in Ottawa.

Thomas D’Arcy McGee’s formative years were spent in Ireland. His mother’s family was reputed to have been involved in the 1798 Irish rebellion. His father worked for the Coast Guard Service, and in 1833 was transferred to Wexford, the town where the memories of the bloody 1798 rebellion were the most vivid. D’Arcy’s mother died shortly after the family’s arrival in Wexford; he obtained an informal elementary education in a Catholic “hedge school.” He was influenced at an early age by Father Theobald Mathew’s temperance movement, by Daniel O’Connell’s campaign to repeal the union between Ireland and Great Britain, and by the work of Celtic scholars published in the Dublin Penny Journal.

D’Arcy McGee left for North America in 1842, one of almost 93,000 Irishmen who crossed the Atlantic that year, the greatest number in any one year before the famine. McGee’s father had married again, and the stepmother was not popular with the children. He travelled the classic route to North America, sailing on a timber ship from Wexford to Quebec, and continuing to New England, where he was welcomed to the home of his mother’s sister in Providence, R.I. He then moved to Boston to look for work. Soon after his arrival he was asked to address the Boston Friends of Ireland celebrating the Fourth of July. It was his first recorded public address in America, and it revealed a hostile attitude towards British rule in Ireland: “The sufferings which the people of that unhappy country have endured at the hands of a heartless, bigoted, despotic government, are well known to you . . . . Her people are born slaves, and bred in slavery from the cradle; they know not what freedom is.” The speech made a favourable impression, and the 17-year-old immigrant was asked to join the staff of the Boston Pilot, New England’s principal Catholic newspaper.

McGee was taken on as the Pilot’s travelling agent, and for the next two years travelled through New England collecting overdue accounts and new subscribers. He also lectured to the scattered Irish population of New England, describing the movements begun in Ireland by Daniel O’Connell and Father Mathew. During the same period he contributed 40 articles to the Pilot on the history of literature in Ireland. The response to his articles was enthusiastic, and McGee was asked to become editor of the newspaper; his first editorial appeared on 13 April 1844, on his 19th birthday.

McGee edited the Pilot for a year. In his editorials he urged the Irish in America to support Ireland’s struggle for nationality, arguing that the Irish in America would never be recognized as equals until Ireland was recognized as a nation. The young editor also defended Irish Catholic immigrants against hostile Protestant and nativist opinion and led a successful campaign for the establishment of evening schools for adult immigrants. He published two books in Boston during his first stay in the United States: Eva MacDonald, a tale of the United Irishmen (1844) and Historical sketches of O’Connell and his friends (1845).

While in Boston, McGee had the opportunity to comment on Canada, and his perspective was distinctly Irish. At first, he urged the Irish in Canada to support Robert Baldwin* and Louis-Hippolyte La Fontaine, and wrote that “‘Repeal of the Union’ is the Irish for ‘Responsible Government.’” When a correspondent informed him that in Canada the Tories were more tolerant towards the Catholic Church, McGee answered: “The Tories! Well may the Catholics of Canada exclaim, ‘Oh, save us from our friends!’” Later, the annexation of Texas and the Oregon boundary dispute led McGee to reconsider his views on Canada and to see it in a new light. He now confessed that he could find no reason for Canada’s remaining separate from the United States: “The United States of North America must necessarily in course of time absorb the Northern British Provinces . . . . One vast Federal Union will stretch from Labrador to Panama. A river like the St. Lawrence cannot safely be left in European hands . . . . Either by purchase, conquest, or stipulation, Canada must be yielded by Great Britain to this Republic.”

McGee was offered in 1845 a position with the Freeman’s Journal in Dublin and in June returned to Ireland. He reported on the proceedings in Dublin of the Repeal Association organized by Daniel O’Connell and then moved to London where he covered the parliamentary session of 1846 which repealed the Corn Laws. While working for the Freeman, however, McGee became closely associated with Young Ireland, an enthusiastic group of Irish nationalists who believed that self-government was a fundamental principle of nationality, and who were trying to develop a sense of Irish identity by their contributions to journalism, history, and literature. McGee contributed two volumes to their “Library of Ireland,” Gallery of Irish writers in 1846 and A memoir of the life and conquests of Art MacMurrogh in 1847. He also began to contribute to the Nation, Young Ireland’s journal. Finally he was asked to resign from the Freeman. McGee transferred to the Nation just after his 21st birthday.

In July 1846, Daniel O’Connell announced his support for the new Whig government which promised Irish reform; McGee supported the leaders of Young Ireland when they resigned from the Repeal Association and established the Irish Confederation to promote what they believed were the original aims of the association, repeal of the union between Ireland and Great Britain. He was a principal speaker at all of the new association’s public meetings and was elected secretary in June 1847. On 13 July 1847 he married Mary Theresa Caffrey in Dublin. The couple were to have five daughters and one son, but only two daughters survived their father.

The Irish Confederation was frustrated in the general elections of 1847, and a radical faction developed which called for armed action. When the radicals were purged from the Confederation at the beginning of 1848 McGee supported the conservative leadership. But the French revolution of February persuaded the conservatives to adopt a revolutionary course of action, and McGee now participated in the plans for an Irish rebellion. He was actually arrested for sedition on the eve of his first wedding anniversary, but the charges were dismissed the next day. The government suspended habeas corpus in Ireland towards the end of July, and the Irish Confederation appealed to the country for armed support. McGee was dispatched to Scotland where he was to collect an expedition of armed sympathizers, but the main resistance did not last two weeks and McGee’s expedition did not embark. He returned to Ireland; when he could not obtain a following in the northeast he left again for the United States.

McGee arrived in Philadelphia in October 1848, and issued a public letter describing recent events in Ireland. He blamed the Irish clergy for the rebellion’s failure and signed the letter defiantly, “Thomas D’Arcy McGee, A Traitor to the British Government.” He then moved to New York City and started his own newspaper, the Nation, in which he tried to arouse American sympathy for the liberal and nationalist revolutions in Europe and supported the annexation movement in Canada as a part of the same cause. His newspaper became a forum for Irish Canadian opinion on the subject. However, McGee antagonized the bishop of New York by supporting the Roman republic against Pope Pius IX, and by the end of 1849 he had alienated Irish republicans in New York when, following yet another shift in position, he began to support a new Irish reform movement which planned to work within the existing Irish constitution. The dispute became personal, and two Irish republicans, who were to become Fenian leaders, challenged McGee to a duel. The combination of clerical and republican opposition forced him to leave New York in the spring of 1850.

McGee returned to Boston where he started another newspaper, the American Celt and Adopted Citizen. He now emphasized Irish interests in America and supported a naturalization campaign among the Irish of New England. He also published A history of the Irish settlers in North America (1851) to demonstrate that the Irish had made a significant contribution to the history of North America. When the pope appointed an English episcopacy in 1851, anti-Catholic opinion was aroused in Britain and America, and McGee, unable to endure the charge made by Catholics that he was contributing to the nativist campaign by attacking the clergy, made his peace with the Catholic Church. He moved the American Celt to Buffalo in the summer of 1852, but it did not prosper. McGee and his newspaper returned to New York City in the summer of 1853.

For the next four years, McGee worked on behalf of the Catholic interests in the United States, condemning revolutionary liberalism as a threat to Christianity and civilization. He completed three books during this period: A history of the attempts to establish the Protestant reformation in Ireland (1853), The Catholic history of North America (1855), and A life of the Rt. Rev. Edward Maginn (1857). Gradually McGee became more critical of the United States, arguing that American society required the tempering influence of Catholicism to balance the disorderly tendencies of the New World. By 1855 he was urging the American Irish Catholics to leave the eastern cities and to found a colony in the newly opening west where they could recover their Celtic and Catholic character. He was the principal organizer of the Buffalo Emigrant Aid Convention of 1856, but the project failed when it aroused the opposition of the Catholic hierarchy in the east who insisted that the Irish had neither the skills nor the capital necessary for colonization. McGee believed, however, that the eastern hierarchy was afraid an exodus of Catholics would jeopardize the financial situation of their dioceses.

In the spring of 1857 McGee moved to Montreal. He came at the invitation of leaders of that city’s Irish community who expected him to promote their interests. His attitude toward Canada had changed from the days when he supported annexation: after his reconciliation with the Catholic Church, McGee defended Canada as a place where Catholic rights were recognized. He had visited Canada in the fall of 1852 and in the winter of 1856. After the Irish rebels of 1848 were granted amnesty, McGee lectured in Ireland in 1855 and urged emigrants to choose Canada over the United States.

In Montreal McGee’s first effort was another newspaper, the New Era, which he published for one year. The newspaper was designed to launch his career in Canadian politics, and it concentrated on attacking the influence of the Orange Order and defending the Irish right to representation in the assembly. McGee also devoted considerable space in the New Era to the future of Canada, and outlined a programme for the development of what he called “a new nationality.” This included proposals for extensive economic development by means of railway construction, the fostering of immigration, and the application of a protective tariff. McGee also urged economic cooperation between Canada and the Maritime colonies and suggested that this would lead to “a federal compact” among the provinces. A federal system, McGee argued, would solve Canada’s constitutional problems and provide for the survival of French Canada. McGee urged Canadian colonization of the Hudson’s Bay Company territory, but, at the same time, called for a policy which would allow for the integration of the indigenous people of the western territory into the new order; his plan included extensive Canadian economic assistance.

McGee’s concept of the “new nationality” was based on the desirability of developing an alternate experience in North America to that of the United States. An essential characteristic of Canada’s experience was its relationship with Great Britain, and McGee’s solution to the problem of retaining the connection between them yet providing for Canadian sovereignty was a proposal that one of Queen Victoria’s younger sons establish a Canadian dynasty in a “kingdom of the St. Lawrence.” Equally important in McGee’s mind was the development of a distinctive Canadian literature. After asking, “Who reads a Canadian book?” he went on to suggest ways in which Canadian literature might be encouraged, including tariff protection for Canadian publishers. Much of McGee’s Canadian programme was derived from the nationalist theories of Young Ireland, and he applied them to the particular circumstances of Montreal and British North America during the economic depression of 1857. Later he described his programme as his “national policy,” and its tenets influenced the course of his public life in Canada.

In December 1857 D’Arcy McGee was one of three members elected to represent Montreal in the Legislative Assembly. He had been nominated by the St Patrick’s Society of Montreal and his property qualification was obtained by public subscription among the Irish community. When the Conservative government nominated Henry Starnes* to oppose him, McGee joined himself with Luther Hamilton Holton* and Antoine-Aimé Dorion* against John Rose*, George-Étienne Cartier*, and Starnes. Rose, Dorion, and McGee were all returned, and it was believed that the Irish vote had decided the contest.

In parliament McGee supported the short-lived Reform government of George Brown* and Dorion during the 1858 session, and when they left office he sat in opposition to the coalition of Cartier and John A. Macdonald*. Outside the assembly, McGee developed a political organization among the Irish Catholics of Canada West and urged them to support George Brown’s Reformers. He also tried to change the Reform party so that it would be acceptable to both sections of the province. At the very time the 1859 convention of western Reformers adopted a federal policy, McGee and three other members of the opposition from Canada East issued a manifesto endorsing a federal union of the two Canadas. It was rumoured that McGee had persuaded the western Reformers to consider the Irish national school system as a model for solving the school problems of Canada West.

McGee’s hopes of winning Irish Catholic support for a reconstructed Reform party under George Brown did not survive long after the 1861 general election when McGee’s school policy was attacked in a public letter signed by the Roman Catholic hierarchy of Canada. McGee was himself re-elected in 1861, but Brown went down to defeat and believed that his failure was due to John Joseph Lynch*, the Catholic bishop of Toronto. McGee’s alliance with Brown ended when Richard William Scott* introduced his separate school bill which the Globe categorically opposed and McGee supported. Nevertheless, McGee continued to oppose the Conservatives after the 1861 election. When the Cartier-Macdonald government was defeated on its militia bill in 1862, McGee was asked to become president of the council in the moderate Reform administration of John Sandfield Macdonald*. McGee immediately went to work on a programme to reform the civil service and tried to have all matters of immigration transferred to his office. Despite his government’s retrenchment policy, McGee urged economic expansion and chaired the Intercolonial Railway conference which met in September 1862 at Quebec. When Sandfield Macdonald’s government supported the railway, Dorion resigned; when the railway scheme fell through, Dorion returned and McGee was dropped from the cabinet. In the general election that followed, McGee announced he would run as an independent and declared: “I intend to adhere to the national policy I have always advocated and acted upon. . . .” The Sandfield Macdonald-Dorion government decided to nominate a candidate to oppose McGee, and McGee then supported Cartier and Rose against Holton and Dorion. On this occasion, McGee, Cartier, and Rose were returned.

As McGee moved from the Reformers to the Conservatives, he renewed his public efforts on behalf of the programme he had outlined in the New Era. During the summer of 1863 he wrote several public letters and contributed two articles to the British American Magazine in which he defined a destiny for British America. British America and the United States, McGee argued, both enjoyed a freedom native to their continent and unknown in Europe. Americans had developed their freedom into a republican system of government, and, although it was a magnificent experiment, it had many shortcomings. British Americans, on the other hand, had not separated from Britain and had developed their institutions along different lines. By retaining a system of constitutional monarchy, they had achieved a better balance between their natural freedom and the need for authority. Their society was more orderly and more free. “To the American citizen who boasts of greater liberty in the States, I say that a man can state his private, social, political and religious opinions with more freedom here than in New York or New England. There is, besides, far more liberty and toleration enjoyed by minorities in Canada than in the United States.” McGee was fond of citing the example of minority rights and he brought this to the attention of the Irish press, contrasting the position of the Irish in “British and Republican North America.” In the summer of 1863 McGee took his appeal for British American nationality to New Brunswick and Nova Scotia. He addressed audiences in Saint John and Halifax, and used the same arguments he had put forward in Canada. “I invoke the fortunate genius of a united British America, to solemnize law with the moral sanction of religion, and to crown our fair pillar of freedom with its only appropriate capital, lawful authority, so that, hand in hand, we and our descendants may advance steadily to the accomplishment of a common destiny.”

McGee became the minister of agriculture, immigration, and statistics in the Conservative government which was formed after the defeat of Sandfield Macdonald’s second administration in 1863. He retained that office in the “Great Coalition,” and was a Canadian delegate to the Charlottetown and Quebec conferences of 1864. At Quebec, McGee introduced the resolution which called for a guarantee of the educational rights of religious minorities in the two Canadas.

The years which inaugurated confederation coincided with a crisis in Ireland, and the crisis touched McGee. The Irish Republican Brotherhood, popularly known as the Fenians, had obtained wide support among the Irish in Great Britain and the United States, and appealed to the Irish in Canada. McGee openly opposed the movement, and based his opposition on two grounds: first, he objected to the republican programme for Ireland and urged the Irish to adopt the Canadian model of self-government within the British Empire; second, McGee attacked the Fenian plan to invade British America and called on the Irish in Canada to “give the highest practical proof possible that an Irishman well governed becomes one of the best subjects of the law and the Sovereign.” When he visited Ireland in 1865 as the Canadian delegate to the Dublin International Exposition McGee addressed an audience in Wexford, the town where he had spent his boyhood, and spoke on the Irish immigrant in Canada and the United States. He also described his career as an Irish rebel as “the follies of one and twenty.” This “Wexford Speech” attracted great attention in Ireland, Britain, the United States, and Canada, and McGee was accused of being a turncoat and a traitor to Ireland.

By 1866, McGee was in political trouble with his Irish constituents in Montreal. He had antagonized the Irish vote and had become a liability in Canadian politics. He was not invited to the London conference in 1866, nor was he included in the first dominion government. As the federal general election of 1867 approached, McGee was expelled from the St Patrick’s Society, and the society’s president, Bernard Devlin*, was nominated to oppose him. Although McGee was returned for Montreal West, he had lost the Irish vote and was defeated as a candidate for Prescott in the Ontario provincial election. He now expressed a desire to leave politics. John A. Macdonald promised him a civil service post for the summer of 1868, and McGee intended to turn his full attention to literature and Canadian history. He was dead before the appointment was made.

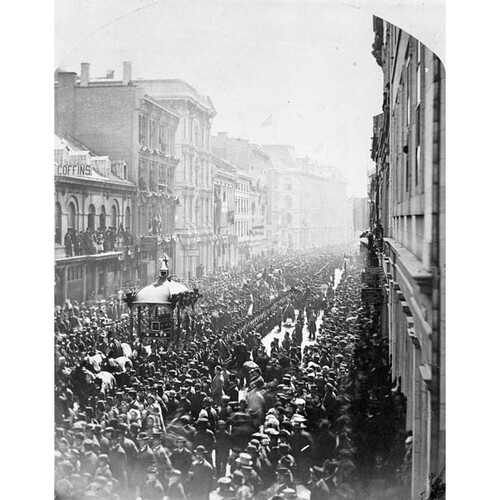

McGee was assassinated in Ottawa during the early morning hours of 7 April 1868. He was buried a week later in Montreal on his 43rd birthday. It was generally believed at the time that his murder was part of a Fenian conspiracy. Patrick James Whelan, an Irish immigrant, was charged with the crime, found guilty, and hanged publicly in Ottawa on 11 Feb. 1869. The crown, however, never accused Whelan of being a Fenian, and the charges against other alleged members of the conspiracy were dismissed.

Aside from his public speeches and newspaper editorials, Thomas D’Arcy McGee left behind a significant body of literature. His first piece, Eva MacDonald, was historical fiction. The only other fiction he wrote was a drama intended for Catholic schools, Sebastian, or the Roman martyr (1861). All of his other prose work was historical, most of it propagandist and designed to justify a present position through historical argument. His best historical work was his last, A popular history of Ireland (1863). Its title was significant: although McGee did some primary research, he depended on the work of other scholars and popularized their discoveries. The work was well received, and he was elected to the Royal Irish Academy.

McGee also published a large number of poems throughout his career under the pseudonym “Amergin,” and 309 of them were collected and published after his death by his close friend, Mary Anne Sadlier [Madden*]. McGee’s poetic style was lyrical when he expressed personal emotion; he used the ballad for historical subjects, and once expressed the ambition to write a ballad history of Ireland. As a poet, he was a part of the Young Ireland school which published in the Nation, and which included Thomas Osborne Davis, James Clarence Mangan, Sir Samuel Ferguson, and “Speranza,” the future Lady Wilde and mother of Oscar Wilde. McGee’s verse, his love of the Celtic past, his interest in history, and his political ideas were all consistent with the romantic milieu in which he lived.

D’Arcy McGee’s personality and private life are difficult to evaluate, as very few of his private papers are available. He was well known for his speaking ability, being generally acknowledged as the finest public speaker in Canadian politics at the time. This ability was apparent from his earlier career, when he obtained a substantial part of his income from lectures and speaking tours. He never enjoyed an independent income, and always depended on writing, journalism, lectures, public subscriptions, and government appointments for income. He was generally in debt, and this condition contributed to the charge that he changed ideological and political positions for personal gain. The truth of this charge is difficult to determine accurately. His early flirtations with revolutionary liberalism and anti-clericalism, followed in later years by a passionate faith in Catholicism and conservatism, was a common pattern among many 19th century romantics. So too was the tendency towards personal escapism. Many prominent romantic personalities were acknowledged to be users of drugs, and McGee was known for his heavy drinking. This pattern of behaviour was most noticeable during times of stress, such as the crisis preceding his reconciliation with the church, the conflict with Sandfield Macdonald, and his confrontation with the Fenians. At the time of his death he had renewed his pledge of total abstinence, a pledge he had first taken from Father Mathew in Ireland.

T. D’A. McGee, The Catholic history of North America; five discourses, to which are added two discourses on the relations of Ireland and America (Boston, 1855); Eva MacDonald, a tale of the United Irishmen (Boston, 1844); Gallery of Irish writers; the Irish writers of the seventeenth century (Dublin, 1846); Historical sketches of O’Connell and his friends . . . (2nd ed., Boston, 1845; 4th ed., 1854); A history of the attempts to establish the Protestant reformation in Ireland, and the successful resistance of that people; (time: 1540–1830) (Boston, 1853); A history of the Irish settlers in North America, from the earliest period to the census of 1850 (Boston, 1851; 5th ed., 1852); A life of the Rt. Rev. Edward Maginn, coadjutor bishop of Derry, with selections from his correspondence (New York, 1857; 2nd ed., 1860); A memoir of the life and conquests of Art MacMurrogh, king of Leinster, from A.D. 1377 to A.D. 1417, with some notices of the Leinster wars of the 14th century (Dublin, 1847; 2nd ed., [1886]); “A plea for British American nationality” and “A further plea for British American nationality,” British American Magazine; Devoted to Literature, Science, and Art (Toronto), I (1863), 337–45, and 561–67; The poems of Thomas D’Arcy McGee; with copious notes; also an introduction and biographical sketch, ed. Mrs. James Sadlier [M. A. Madden] (New York, 1869); ed. Brady (2nd ed., Boston, 1869), A popular history of Ireland . . . (2v., New York, 1863).

Georges P. Vanier Library (Concordia University, Montreal), G. E. Clerk diary, 18 Sept. 1856–21 Dec. 1857; T. D’A. McGee coll. PAC, MG 24, B30; C 16; MG 26, A, 46, p.18010; MG 27, I, E9; E12; III, B8; MG 29, D15; RG 1, E7. Royal Irish Academy (Dublin), Minute book of the Irish Confederation, 26 June 1847. American Celt (Boston, Buffalo, N.Y., and New York), 31 Aug. 1850; 31 May, 8 Nov. 1851; 18 May, 11 June 1853. Boston Pilot, 9 July 1842, 13 April 1844–17 May 1845, June 1845–May 1846, 7 Aug. 1847, 21 Oct. 1848. Gazette (Montreal), 3, 12 June 1863; 9 Dec. 1865; 15 April 1868. Globe, 13 Aug. 1858, 23 Aug. 1859. Montreal Herald, 26 Nov. 1856. Nation (Dublin), 19 Sept. 1846; 5 Feb., 15 July 1848; 22 June 1850; 8 March 1851; 4 Sept., 11 Dec. 1852; 2, 9 June 1855; 8 March 1856; 13, 20 May 1865. Nation (New York), 20 Jan., 31 March, 14 April, 1 Dec. 1849; 27 Jan. 1850. New Era (Montreal), 25 May 1857–1 May 1858. W. F. Adams, Ireland and Irish emigration to the New World from 1815 to the famine (New Haven, Conn., 1932). E. R. Cameron, Memoirs of Ralph Vansittart (Toronto, [ 1924]), 101–2. H. J. O’C. Clarke, A short sketch of the life of the Hon. Thomas D’Arcy McGee, M.P., for Montreal (West) . . . (Montreal, 1868). C. G. Duffy, My life in two hemispheres (London, 1898); Young Ireland; a fragment of Irish history (2v., London, 1880–83), II. M. G. Kelly, Catholic immigrant colonization projects in the United States, 1815–1860 (New York, 1939). Isabel [Murphy] Skelton, The life of Thomas D’Arcy McGee (Gardenvale, N.Y., 1925), 373. T. P. Slattery, “They got to find mee guilty yet” (Toronto and Garden City, N.Y., 1972). [J.] F. Taylor, Thos. D’Arcy McGee: sketch of his life and death (Montreal, 1868).

Revisions based on:

Bibliothèque et Arch. Nationales du Québec, Centre d’arch. du Vieux-Montréal, CE601-S51, 13 avril 1868. National Library of Ireland (Dublin), “Catholic parish registers,” Dublin city, St Andrew’s, 06610/01 (mfm), 13 July 1847: registers.nli.ie (consulted 21 Jan. 2020). Canada, Prov. of, Legislative Assembly, Journals, 1858.

Cite This Article

Robin B. Burns, “McGEE, THOMAS D’ARCY,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 9, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 28, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mcgee_thomas_d_arcy_9E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mcgee_thomas_d_arcy_9E.html |

| Author of Article: | Robin B. Burns |

| Title of Article: | McGEE, THOMAS D’ARCY |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 9 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1976 |

| Year of revision: | 2020 |

| Access Date: | March 28, 2025 |