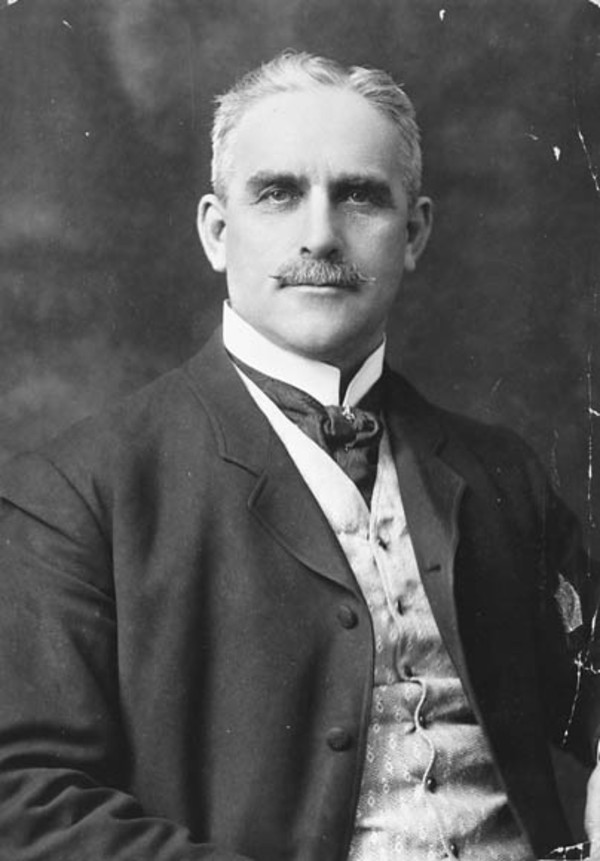

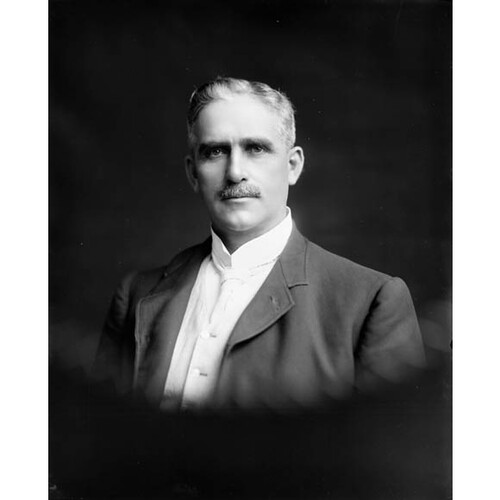

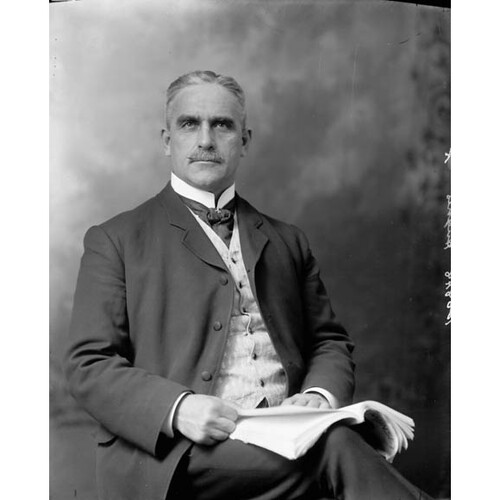

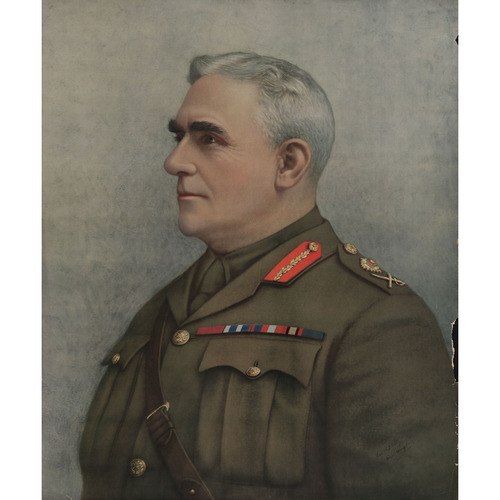

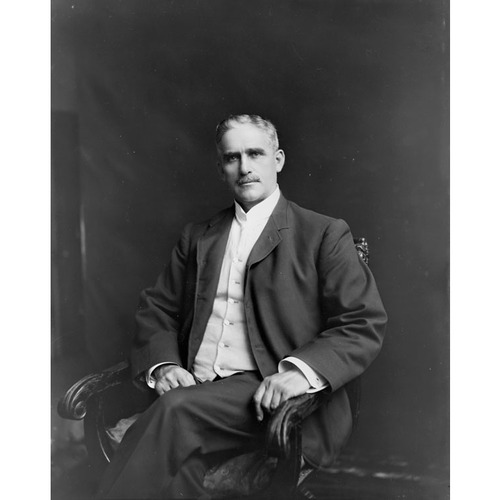

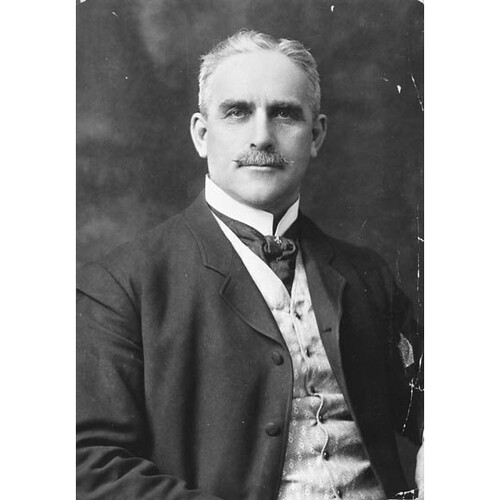

HUGHES, Sir SAMUEL, teacher, militia officer, newspaper proprietor, and politician; b. 8 Jan. 1853 in Darlington Township, Upper Canada, son of John Hughes and Caroline Laughlin; m. first 1872 Caroline J. Preston (d. 1873); m. secondly 5 May 1875 Mary Emily Burk in Darlington, and they had a son, Garnet Burk*, and two daughters; d. 24 Aug. 1921 in Lindsay, Ont.

Sam Hughes’s father emigrated from Ireland to Durham County, Upper Canada, in the 1840s and made his living as a farmer and a schoolteacher. He married the daughter of a British artillery officer serving in the colony, and they raised a large family: four sons, of whom Sam was the third, and seven daughters. Sam took his early education in the public schools of Durham and at home, where he read widely with a special interest in travel accounts and military campaigns. As a young man, he developed a love of fishing, hunting, and organized sports; he became a competitive runner and a particularly aggressive lacrosse player. His fondness for hunting would continue throughout his life. He left school after his 16th birthday to become a primary teacher and to attend the Toronto Normal School, where he earned a first-class certificate.

In 1872 Hughes married Caroline Preston, one of his students and a daughter of a farmer in Manvers Township. Soon afterwards he found work with a railway company in Milwaukee, Wis. Caroline’s sudden death a year later brought him back to Ontario to resume teaching, in Bowmanville, and then take up accounting. In 1875 he took a second wife, the daughter of Harvey William Burk, a well-to-do farmer who was also the Liberal mp for Durham West. Mary and Sam moved to Toronto, where his brother James Laughlin* was a school inspector. After a brief apprenticeship in law, Sam began teaching English and history at the Toronto Collegiate Institute. He took courses in history and modern languages at the University of Toronto on a part-time basis, earned a provincial school-inspector’s certificate, and played lacrosse. His abiding interest, however, was the active militia, in which he would serve for more than half a century. He had joined a rifle company of the 45th (West Durham) Battalion of Infantry in 1866 and he climbed through its ranks to become a lieutenant in 1873 and captain and adjutant five years later.

In 1885 Hughes gave up teaching and purchased the Victoria Warder, a Conservative newspaper in Lindsay. As its editor and proprietor, he vigorously supported the Conservative party and, while it was in power in Ottawa under Sir John A. Macdonald*, he enjoyed the favour of government advertising in his paper. He founded the Victoria County Rifle Association and became a member of the Lindsay Board of Trade, the freemasons, the Oddfellows, and the Orange order. In 1888 he sat on the provincial organizing committee of the Imperial Federation League, which championed the interests of British imperialism in Canadian affairs.

In Victoria South, a federal constituency where religion and politics were the most comfortable of bedfellows, Hughes, a Presbyterian turned Methodist, used the Warder to promote imperial centralization and a strident anticatholicism. As well, he maintained an unshakeable belief in the militia as a force better suited to Canada’s requirements than the small, professional Permanent Force, which was commanded by a British officer. Hughes’s positions, which sat well with the Conservatives of Victoria South, except for a small group of Catholics, helped him rise to prominence in the local party organization. The opportunity to advance his ideas on a larger stage came in 1891 when he challenged the Liberal incumbent in Victoria North, John Augustus Barron, for his seat in the House of Commons. Hughes was badly beaten but he contested the election, won his case, and was returned in a by-election the next year. He would hold the seat (which became Victoria and Haliburton in 1903) until his retirement from politics in 1921.

Hughes was a backbencher in the troubled years after Macdonald’s death in 1891, when four successive prime ministers struggled to keep the fractious Tory party together. The Manitoba school issue dominated the religious politics of these years [see D’Alton McCarthy*]. Hughes seldom missed an occasion to denounce the Catholic Church’s promotion of separate schools in Manitoba. Just as frequent were his advocacy of the active militia and his outspoken criticism of the dominion’s Permanent Force. In 1894 he engaged in a public feud with its general officer commanding, Major-General Ivor John Caradoc Herbert*, over Herbert’s plan to make the force the core of Canada’s defence. For his part, Herbert complained openly about Hughes’s persistent efforts to use his elected position and his place in the West Durhams to get militia appointments for his Tory comrades.

Hughes supported Sir John Sparrow David Thompson* during his prime ministership, was unenthusiastic about Sir John Joseph Caldwell Abbott* and Sir Mackenzie Bowell*, and welcomed Sir Charles Tupper* when he returned from England to lead the Tories in the general election of 1896. On the Manitoba school issue Hughes favoured neither the remedial measures Thompson, Bowell, and Tupper had advanced nor the extremism of the opponents of remedial action in the Orange order [see Nathaniel Clarke Wallace*]. Distrustful of all organized churches as “the greatest enemy of civilization,” he was an uncompromising champion of secular education controlled by the state. In the election the Liberal party, led by Wilfrid Laurier*, soundly defeated the Conservatives. Hughes held his seat by 338 votes.

Accustomed to the privileges of power, the Conservatives were now in opposition. It was a difficult time for Hughes. There was no patronage to bestow and the Warder was not a financial success. Nor were his efforts to sell a ventilating system for railway cars, as president of the Hughes Ventilator Car Company, the limited stock company that he had formed in 1894 along with William Mackenzie, James Ross*, and other capitalists. In 1898 Hughes gave up the company and the Warder to pay off his debts. In later years his fortune would pick up, largely through highly rewarding investments in Standard Oil and Imperial Oil, but that recovery was far in the future. As the century came to a close, his business ventures were only sources of trouble. He found personal compensation in the militia where, in 1897, he had been given command of the 45th Battalion and promoted lieutenant-colonel.

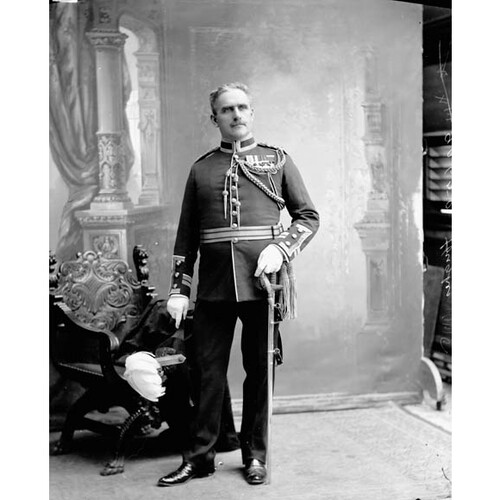

Two years later, on the eve of the South African War, Hughes, as the 45th’s commander, impetuously wrote to the colonial secretary, Joseph Chamberlain, and to the Canadian minister of militia and defence, Frederick William Borden*, offering to lead a regiment or brigade. With almost certain deliberation, he bypassed his superior officers and angered the goc, Major-General Edward Thomas Henry Hutton. In due course the government sent a volunteer force under a distinguished Permanent Force officer, Lieutenant-Colonel William Dillon Otter, who wanted no part of Hughes because of his unruly nature and lack of “professional qualifications.” Hughes nonetheless joined them, as a civilian.

Once in South Africa, in the spring of 1900, he used his influence with British friends to gain command of a small force of irregulars fighting behind the main line of battle, under a British lieutenant-general, Sir Charles Warren. In two brief campaigns Hughes had some success clearing out pockets of Boer resistance. He was proud of his display of leadership. In a series of letters to newspapers at home and in the Cape Colony he boasted of his exploits, continued his fulminations against Hutton, and criticized the competence of the senior British command. Together with his refusal to carry out a crucial order from Warren, Hughes’s outrageous letters swiftly led to his dismissal by the British army with orders to return to Canada. He was humiliated and angry. Blind to his own arrogance and wilful disregard for authority, he believed not just that he had been wrongfully dismissed, but that he had been denied not one but two Victoria Cross awards for his bravery. The episode hardened his lack of respect into a lasting distrust of professional soldiers, be they British or Canadian.

When the Tory caucus received Tupper’s resignation as party leader in November 1900, Hughes was in Ottawa. He and the new leader, Halifax lawyer Robert Laird Borden*, were very different men, but they would support each other for nearly a generation. Hughes had learned his politics in the 19th century, Borden was learning his in the 20th. The mp for Victoria North was a skilful practitioner of inflammatory rhetoric, back-room deals, and parish-pump patronage. Borden’s speeches read like legal briefs. His goal was to rebuild the Conservative party with a future-oriented outlook; nevertheless, over his ten years as leader of the opposition, he depended heavily on old warriors such as Hughes. Many, including Hughes, resisted Borden’s efforts to democratize the party’s national organization, and there were open revolts against Borden, but Hughes was not part of them. However much he and his leader differed on party matters, however much he disliked the business-minded reformers whom Borden attracted into the party, he remained loyal. When Borden suffered personal defeat in 1904, Hughes was the first to offer him a seat, a favour he never forgot. In 1910 and 1911, when factions within caucus again challenged Borden’s leadership, Hughes stood by him. Borden, Hughes told a crony in March 1911, was “very capable, but not a very good judge of men or tactics; and is gentle hearted as a girl.”

In the early and middle years of the Laurier period, the government, led by its capable minister of militia and defence, Frederick Borden, had initiated a number of reforms designed to expand the militia and bring it directly under government control. Hughes, who encouraged the reforms, was especially interested in the Ross rifle, which the minister had adopted as the rifle for Canada’s forces late in the South African War. The War Office was opposed to Canada having a rifle other than the Lee-Enfield, the standard imperial issue. Borden countered with a bipartisan selection committee of mps, including Hughes, which vigorously “pumped” the Ross. Ultimately Hughes would become the fiercest champion of the Ross, a symbol of all the virtues he assigned to the volunteer citizen soldiers of the militia. And, ultimately, this championship would jeopardize his career in World War I.

In September 1911, after campaigning on the naval issue in Quebec, the reciprocity issue in English Canada, and Liberal corruption everywhere, R. L. Borden’s party returned to power. Only four days after the votes were counted, Hughes wrote to Borden seeking appointment as minister of militia and defence. The prime minister read of Hughes’s dark fears that others were conspiring against him, of his service to the party and to Borden, and of his distinguished military record. “In your coming Cabinet operations difficulties may from time to time arise,” Hughes advised. “It strikes me that it might be that again, my tact, firmness and judgement might come in to help matters along.” He concluded by telling Borden that “in my walks through life easy management of men has ever been one of my chief characteristics – and I get the name of bringing success and good luck to every cause.” Men first elected just days before, and others from Borden’s select group of “new style” politicians, were offered places in cabinet. Hughes, like another veteran of 19th-century political wars, George Eulas Foster*, waited. Finally, Borden summoned Hughes. “I impressed strongly upon him the mischievous and perverse character of his speech and conduct,” Borden later recalled. “He broke down, admitted that he often acted impetuously, and assured me that if he were appointed I could rely on his judgment and good sense. This promise was undoubtedly sincere but his temperament was too strong for him. He was under constant illusions that enemies were working against him.” Hughes was sworn in along with the rest of cabinet on 10 October.

Once in office he opposed Borden’s attempts to reform the inside (Ottawa-based) civil service and strongly resisted having his department’s spending brought under the control of the Department of Finance. He pestered Borden to have him promoted to the rank of major-general, and in 1912 Hughes forced through the Militia Council a general order allowing for such promotion of a civilian minister. Patronage in militia and defence was as old as the department itself, its muscle and bone in one of the most politically oriented departments of the pre-war government. This was Hughes’s environment and one in which, he told the commons on 7 March 1913, “I am the boss while I am here.” He worked tirelessly to build up the militia to unprecedented levels of strength, to improve equipment and training, to construct new armouries and drill-halls (59 by 1915), and to push for a second dominion arsenal, at Lindsay. At the same time, between 1911 and 1914, he ignored recommendations from his senior staff officers that the Permanent Force be expanded, to supervise the training of the growing militia. He evinced equal disinterest in his staff’s efforts to formulate defence plans. Steps to prepare a war book for Canada, to address anticipated hostilities in Europe, originated not with Hughes but with Sir Joseph Pope of the Department of External Affairs, in January 1914.

That spring Hughes’s departmental budget was nearly twice what it had been in 1911. No Canadian could have imagined that a few months later the commons would pass (with scarcely any debate) an initial war appropriation of $50 million, that Hughes would take personal responsibility for raising more than 30,000 men for the Canadian Expeditionary Force, and that censorship would be instituted under his control [see Ernest John Chambers].

In the beginning, Sam Hughes had a very good war. An expeditionary force was authorized by cabinet on 6 Aug. 1914 and Hughes, ignoring the mobilization plans prepared by his chief of staff, Willoughby Garnons Gwatkin, sent flurries of contradictory orders across the country. Instead of gathering the force at Petawawa, an established training site in Ontario, he ordered the men to report to Valcartier, an undeveloped site near Quebec City. His contractors, under the direction of William Price, had a huge camp ready there in less than three weeks; its first commander was Hughes’s brother John. In late September, amidst more confusion, the 1st Division of the CEF began boarding hastily assembled transports at Quebec, several thousand men overstrength. It landed in England on 15 October. On the 22nd Hughes was finally gazetted major-general. To give him seniority of rank over his chief of staff, the promotion was backdated to 1912, when his appeal had started.

On his way to England to consult with the division’s commander, Lieutenant-General Edwin Alfred Hervey Alderson, Hughes had announced in New York on the 7th that Canada “could send enough men to add the finishing touches to Germany without assistance either from England or France.” In England, without Borden’s knowledge, he appointed Colonel John Wallace Carson as his “special representative.” Carson was joined by Sir William Maxwell Aitken*, another irregular appointment, as “Canada’s eye-witness” in the first stage of a series of Hughes nominations that thoroughly confused the War Office.

By early November Hughes was back in Canada and recruiting for a second division was well underway. In January 1915, as the 2nd Division was preparing to embark [see Sir Samuel Benfield Steele*] and the 1st was in final training before going to the front, Hughes authorized recruitment for a third division. Voluntary recruiting continued successfully throughout 1915 but began to fall off sharply in the early months of 1916, after Borden had increased the level of Canada’s force to 500,000. In the last six months of 1916 a mere 2,810 men were sent overseas.

Sam Hughes was everywhere, except in his office in Ottawa. Biographer Ronald G. Haycock notes that between August 1914 and November 1916 he was out of the country one-third of the time. When in Canada he rushed from one camp or speech to another, inspecting “his boys,” promoting recruiting, making promises and issuing orders unknown to his department, and lashing out at a growing list of critics. They were, he told a crowd in London, Ont., “yelping like a puppy dog chasing an express train.” “I am loved by millions,” he assured his prime minister. Borden, who sincerely admired Hughes’s work at Valcartier, defended his colleague, praising his energy and enthusiasm. On 24 Aug. 1915, on nomination from Colonial Secretary Bonar Law, Hughes was made a kcb (military) while in England with the prime minister. “He has earned it,” Borden wrote in his diary.

But behind the scenes, Borden grew increasingly concerned about Hughes’s management of Canada’s military effort. Hughes continuously confused his roles as a senior militia officer and as a minister of the crown, and the latter always took second place. Borden had reprimanded him in December 1914 for running his department without informing or getting the approval of the Militia Council. In September 1915 he criticized him for his long absences from his office: “Your first duty is to administer your Department.” Hughes untruthfully retorted that he met his subordinates “more than all the other Cabinet Ministers put together consult theirs,” adding that “I, as the responsible Minister, and having an experience second to none in any Department and far superior to many, and generally being considered as endowed with some common sense, will certainly not delegate my responsibility to any subordinate officer in my Department, or to any Militia Council in my Department.”

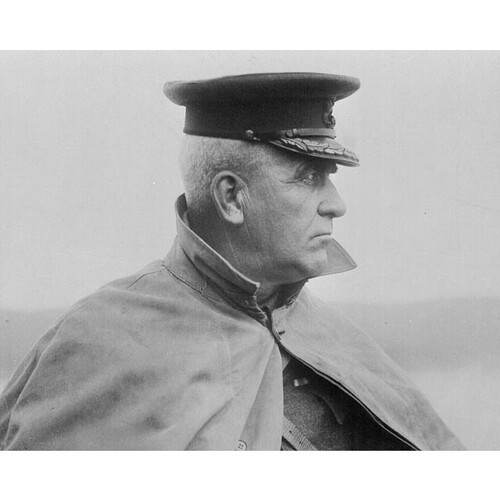

There were other problems – many of them. Overseas, though Hughes continually boasted of the superiority of Canadian equipment over British issue, Alderson had had to replace the 1st Division’s boots (developed for use in the South African War), webbing, and other equipment before the troops left for the front. In their first battle in the Ypres salient, their Ross rifles failed. “It is nothing short of murder to send our men against the enemy with such a weapon,” one officer reported. Alderson replaced the Ross with the Lee-Enfield in June, thus ensuring his status as an enemy of Sam Hughes.

Overseeing the expenditure at home of millions of dollars for supplies and equipment for recruitment and the CEF, Hughes had been joined by a committee of fellow cabinet ministers well tutored in the art of allocating patronage. Though Hughes was not responsible, there were scandals over the purchase of drugs, horses, and other materials. Two Conservative mps turned out to be the culprits in the drugs and horses scandals and they were thrown out of caucus by Borden. In June 1915 he appointed Sir Charles Peers Davidson, former chief justice of the Superior Court of Quebec, to investigate purchasing. Meanwhile, Hughes’s Shell Committee, formed in September 1914 to implement the manufacture of munitions in Canada for the allied governments, struggled to get orders and, when it did, struggled to fill them. Ugly rumours abounded that financier-manufacturer John Wesley Allison, a Hughes crony and an honorary colonel, was profiting hugely from Shell Committee contracts. In April 1916 Sir William Ralph Meredith, chief justice of Ontario, and Lyman Poore Duff* of the Supreme Court of Canada constituted a commission to examine charges against Allison and the work of the Shell Committee.

Though the commission would exonerate Hughes, he was increasingly a problem. As the war grew in intensity and expense, as more and more men were shipped overseas, the voluntary spirit and pluck that characterized Hughes’s leadership became out of place, inefficient, and outdated. On both the European front and the home front, professionalism and orderly management and execution were required. Hughes never understood or accepted the change that swirled about him. Gradually, the prime minister removed more and more of his responsibilities and placed them in other, more capable hands. In May 1915 the management of spending for supplies had been assigned to the newly formed War Purchasing Commission, chaired by Toronto manufacturer and mp Albert Edward Kemp. In November the Shell Committee was replaced by the Imperial Munitions Board, responsible to the British Ministry of Munitions and headed by Joseph Wesley Flavelle*, another Toronto businessman with an impeccable reputation. The following spring, during the Shell Committee investigation, Borden took over administration of Hughes’s department. Then, in June 1916, he appointed Fleming Blanchard McCurdy*, a Nova Scotia mp and financier, as parliamentary secretary of the department to assist Hughes and “provide for continuity in the conduct of the Department’s business and business policy.”

After initial protests, Hughes took much of this takeover in stride. His attention by 1916 was almost solely concentrated on the overseas forces. At the front the Canadian Corps fought within the British armies. In England the CEF had an autonomous command structure but was in complete disarray. Hughes failed to straighten things out during a trip in March and April. Called home during the Shell Committee investigation, he made a whirlwind tour of eastern Canada – in Ontario he opened Camp Borden on 11 July – but he returned to England later that month. At the end of July Borden instructed him to send back his recommendations for approval by cabinet. Follow-up queries in August were ignored by Hughes.

“I do not mind fault-finding by my enemies,” he wrote Borden on 1 September. “You have never known me fail you in anything yet,” he boasted, but he was doing just that. Borden learned in the press on the 6th that Hughes had created a “Sub-Militia Council,” with Major-General Carson as its president, in direct violation of Borden’s instructions. It had met, in further violation, the day before. Hughes, at last, had gone too far. He was, Borden wrote, “wrong-headed and stupid as ever.” Borden took his remaining responsibilities away, created the Ministry of Overseas Military Forces of Canada, and appointed his trusted friend Sir George Halsey Perley*, the acting high commissioner in London, as minister. Hughes was summoned home. When the new ministry was announced at the end of October, he wrote an “impertinent” letter to Borden criticizing his demands for constitutional and orderly procedures and accusing the prime minister of joining the nest of conspirators. On 9 Nov. 1916 Borden demanded his resignation. It was tendered two days later. Kemp replaced Hughes as minister of militia and defence. “The nightmare is over,” Sir George Foster observed.

Hughes told Borden on the 15th that he had left cabinet “with regret, not on account of the office or anything special, outside of friendships which will last – but for the welfare of the soldiers,” adding that “a kindly, watchful eye will be kept over them by your humble servant.” He remained in parliament, keeping a watchful, not always kindly, eye on Borden. The following spring, apparently impatient that the prime minister had taken so long to introduce conscription, Hughes tried to drum up support for a conscriptionist third party, headed by himself. He failed. In the fall he opposed Borden’s plan for a union government, but he then ran successfully as a Unionist candidate in the general election in December 1917. On 1 Oct. 1918, while the Canadian Corps was in a fierce battle at Cambrai, he wrote to Borden accusing its commander, General Sir Arthur William Currie*, of the “needless massacre of our Canadian boys.” In the debate over the throne speech the following March, Hughes, in a vicious attack on the Union government, his former colleagues, and Flavelle, made his letter public. Currie, he went on, had sacrificed the lives of even more Canadian soldiers in his attack on Mons and should be “tried summarily by court martial and punished so far as the law would allow.” Hughes was protected from charges of libel by parliamentary privilege. Despite spirited defences of Currie in the days that followed, the ugly smear would persist until his vindication in a celebrated trial in 1928.

Hughes’s shameful speech was, perhaps, the most outrageous act in his long public career of colourful and irresponsible behaviour. On 6 Oct. 1919 he stood up in the commons to proclaim that he had initiated or urged much of Canada’s apparatus of war, including defensive trenches and numerous kinds and placements of weaponry. He was 66, bitter, and physically failing. The war had ruined both his career and his health. In the winter of 1915–16 he had been in hospital for some weeks; in March 1916 he advised Borden he was suffering from insomnia and had been told by his doctor that he had some marked irregularity in the action of his heart. In 1917, after his dismissal from cabinet, he began building an impressive summer home, Glen Eagle, in Guilford Township in the Haliburton highlands, but whatever rest he got there did not help. By the fall of 1920 he was bedridden in Ottawa, diagnosed as a victim of the then lethal disease, pernicious anaemia. Major-General Sir Sam Hughes died at his home in Lindsay on 24 Aug. 1921, and was buried with full military honours.

AO, RG 22-357, no.3322; RG 80-5-0-212, no.6180. NA, MG 26, H; MG 27, II, D9. R. C. Brown, Robert Laird Borden, a biography (2v., Toronto, 1975–80). R. C. Brown and Donald Loveridge, “Unrequited faith: recruiting the CEF, 1914–1918,” Rev. internationale d’hist. militaire, no.[54] (éd. canadienne, Ottawa, 1982): 53-79. Can., Parl., Sessional papers, 1915–19. Canadian annual rev., 1914–19. John English, The decline of politics: the Conservatives and the party system, 1901–20 (Toronto, 1977). J. L. Granatstein and J. M. Hitsman, Broken promises: a history of conscription in Canada (Toronto, 1977). R. G. Haycock, Sam Hughes: the public career of a controversial Canadian, 1885–1916 (Waterloo, Ont., 1986). A. M. J. Hyatt, General Sir Arthur Currie: a military biography (Toronto, 1987). J. A. Keshen, Propaganda and censorship during Canada’s Great War (Edmonton, 1996). Desmond Morton and J. L. Granatstein, Marching to Armageddon: Canadians and the Great War, 1914–1919 (Toronto, 1989). Nicholson, CEF. Nila Reynolds, In quest of yesterday (3rd ed., Minden, Ont., 1973). R. J. Sharpe, The last day, the last hour: the Currie libel trial ([Toronto], 1988).

Cite This Article

Robert Craig Brown, “HUGHES, Sir SAMUEL,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 1, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hughes_samuel_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hughes_samuel_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | Robert Craig Brown |

| Title of Article: | HUGHES, Sir SAMUEL |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2005 |

| Year of revision: | 2013 |

| Access Date: | January 1, 2026 |