Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

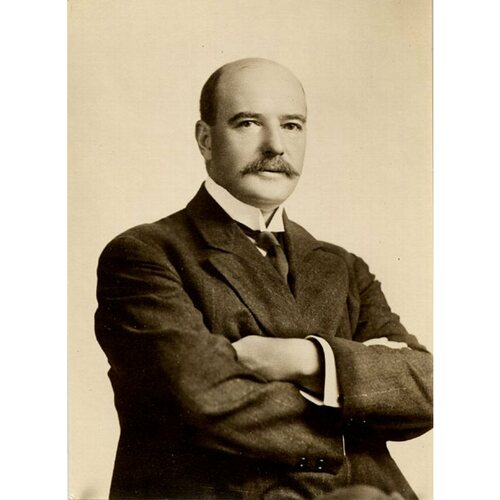

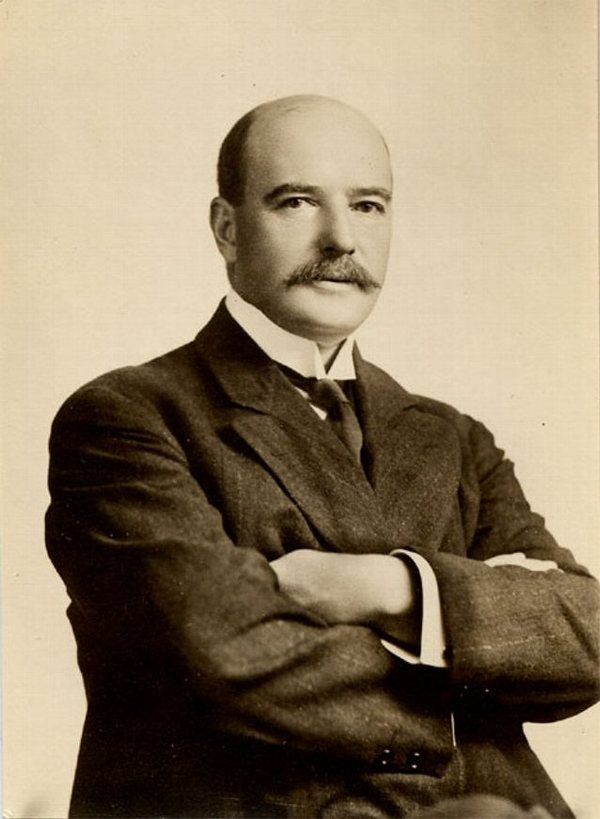

PRICE, Sir WILLIAM, businessman, industrialist, officer, and politician; b. 30 Aug. 1867 in Talcahuano, Chile, son of Henry Ferrier Price, a businessman, and Florence Rogerson; m. 25 Jan. 1894 Amelia Blanche Smith at Quebec, and they had four sons and two daughters; d. 2 Oct. 1924 in Kénogami (Jonquière), Que., and was buried there on 13 Oct. 1924 in the cemetery of St James Anglican Church.

William Price spent his early childhood in Chile, where his father, the son of the late William Price*, an important lumber merchant in Quebec, was a cattle breeder. When he was about five years old, his parents sent him to Canada. He was educated first at Bishop’s College, in Lennoxville, Que., and later at St Mark’s School in Windsor, England. His classmates nicknamed him Chile Price. In 1885 he embarked on a career in the lumber trade with the Quebec firm of Price Brothers and Company, which was owned by his uncle, Evan John Price*.

From 1885 to 1899 William participated in making the administrative decisions of the firm, which by then owned vast timber limits in many parts of the province. During the last three decades of the 19th century, the company invested in numerous sawmills, which were located at Cap-Chat and Matane in the Gaspé region, Saint-Firmin (Baie-Sainte-Catherine) and Sault-au-Cochon (Forestville) on the north shore of the St Lawrence, Montmagny, Cap-Saint-Ignace, and Trois-Saumons (Saint-Jean-Port-Joli) on the south shore of the St Lawrence, Trois-Pistoles, Saint-Germain-de-Rimouski (Rimouski), Saint-Octave-de-Métis (Grand-Métis), and Le Bic in the lower St Lawrence region, Chicoutimi and Grande-Baie (La Baie) in the Saguenay region, and Saint-Romuald near Lévis.

Evan John Price died in August 1899. By the terms of his will, his nephew William took over the management of Price Brothers and Company, which, because of the decline in shipbuilding and in timber exports at the port of Quebec, had been caught in an economic downturn since the 1880s. Although the company’s financial resources were estimated to be between $500,000 and $1 million in July 1900, they had become so shaky that it was on the brink of bankruptcy. That year its principal creditor, the Bank of Montreal, appointed an outside administrator, Robert Ritchie, to represent it and he helped Price to straighten out his firm’s affairs.

At the beginning of the century a major change of direction took shape at Price Brothers. While retaining interests in sawmills, Price turned to a new sector: pulp and paper. In 1901 he founded Montmagny Light and Pulp Company and bought the Compagnie de Pulpe de Jonquière. The former, which was equipped with four grinders and four wet machines, could produce nearly 18 tons of pulp a day. This pulp was used to supply the latter company, which had been founded in 1899 by merchants and farmers in Jonquière and specialized in manufacturing cardboard. In 1902, in partnership with Oswald Austin Porritt, who managed the sawmill in Saint-Germain-de-Rimouski, Price founded a joint-stock venture there, the Price-Porritt Pulp and Paper Company. The enterprise, with a capital of $250,000, produced mechanical pulp and cardboard from wood, using hydroelectric resources that it counted on harnessing; it would remain in operation until 1927. He next began a lengthy restructuring of Price Brothers and in 1904 it was incorporated. Price Brothers and Company Limited, with share capital of $2 million and a head office at Quebec, became the parent company of the Compagnie de Pulpe de Jonquière, Montmagny Light and Pulp Company, and Price-Porritt Pulp and Paper Company. The members of its first board of directors were William Price, Henry Edward Price, Robert Ritchie, Gustavus George Stuart, and Andrew Thomson*, all from Quebec City, Edward George Price and Ion Hamilton Benn of London, England, Granger Farwell of Chicago, and William S. Hofstra of New York.

Price continued to operate businesses elsewhere in the province, but from now on most of his industrial activity was carried out in the Saguenay region. Chicoutimi was his main centre of action in this region until 1902, when, as a result of a few misfortunes, he moved his operations to Jonquière. In 1900 there had been an initial lawsuit over the ownership of the quays located at Chicoutimi, in the basin of the Rivière Saguenay. Built by Price Brothers some 30 years earlier and maintained by them, these quays were considered a waterfront lot belonging to the crown and were sold by the provincial government to the Chicoutimi Pulp Company [see Julien-Édouard-Alfred Dubuc*]. Four years later, the disputes continued with the sale of the sawmill in Chicoutimi, which was immediately demolished by the new owners. Moreover, the Price family’s monopoly on the lumber industry in the region [see Evan John Price; William Price] came increasingly under attack from some of the leading citizens of Chicoutimi [see Joseph-Dominique Guay]. The clashes occurred mainly around 1906, when plans for constructing an aqueduct and electrifying Chicoutimi led to confrontations in the municipal council. Price – who was accused by his detractors of being opposed to progress – did not favour these local initiatives, which threatened to trigger a substantial increase in municipal taxes.

Business was going well, however. In 1905, when its principal trustee, the Bank of Montreal, issued a series of bonds to the value of $1 million, the total assets of Price Brothers were estimated at $4,317,500. Since the beginning of the new century, the firm had made profits estimated at more than $1,200,000. The Prices owned most of the shares: 83.8 per cent in 1907, 83.3 per cent in 1908, and 87 per cent in 1909. Of these family assets, William owned 79.2 per cent in 1907, 78.7 per cent in 1908, and 79.5 per cent in 1909.

The Compagnie de Pulpe de Jonquière had a particularly profitable factory. Equipped with six grinders, it gradually phased out the production of cardboard from mechanical pulp, in favour of producing paper from chemical pulp. A water slide carried the pulp, cardboard, and paper down three miles to the Rivière Saguenay. The factory was powered by its own hydroelectric station, which also served the village of Jonquière. In 1911 it would produce almost equal quantities of pulp and manufactured forest products: 8,000 tons of mechanical pulp, 2,600 tons of sulphite pulp, 6,000 tons of cardboard, and 4,000 tons of paper. It would remain in operation until the end of the 1950s.

In 1910 Price Brothers and Company Limited became Price Brothers Limited and increased its registered capital to $5 million. It specialized increasingly in the production of paper, for a market which the government of Sir Lomer Gouin hoped to stimulate that year by banning the export of pulpwood taken from crown lands. In 1911 Price Brothers began building a new paper mill, which led the following year to the creation of Kénogami, a municipality that was then estimated to have a population of nearly 4,000. The industry, whose source of electricity was a power station with a capacity of nearly 33,000 horsepower, manufactured 150 tons of paper a day from the time it went into production in December 1912.

Even after investing $2.5 million in infrastructure, Price Brothers estimated its profits at some $460,000 at the end of the fiscal year 1911–12. Its assets were evaluated at $15 million and 85.5 per cent of the $6 million in first-mortgage bonds had already been put on the financial market. Price continued to serve as chairman of the board of directors.

Canada’s entry into the war, however, disrupted Price’s life. An ardent patriot and imperialist, he had already put in a number of years of military service. He was an officer with the 8th Regiment (Royal Rifles) and had raised two companies during the South African War. Promoted lieutenant-colonel, he was appointed by Samuel Hughes, the minister of militia and defence, to take charge of all aspects of organizing the camp at Valcartier, near Quebec City. The work began on 10 Aug. 1914, with the electrification of the camp and the construction of an aqueduct, various buildings, and a railway siding. By 25 August, 20,000 soldiers had arrived at the camp, and within two weeks there would be 32,665. As the person in charge of embarking troops and military equipment, Price had to cope with inexperienced staff. Embarkation orders disregarded, congestion in the port of Quebec, and vessels ill-suited to transporting cannons and trucks were some of the factors that led to chaos. On 5 October, when the last of the 31 ships sailed, his nightmare came to an end. His efforts were rewarded with a knighthood on 1 Jan. 1915.

Price now took a personal hand in recruiting and equipping the 171st Infantry Battalion, with which he arrived at the military camp in Witley, England, on 12 Jan. 1917. At the end of the month, after his unit had been disbanded, he became captain of the 4th Battalion, Canadian Railway Troops and went across to France. His military duties were purely administrative. In March 1917 he was transferred to the 87th Infantry Battalion (Canadian Grenadier Guards) as supply officer attached to the 4th Division. Suffering from fatigue, he obtained his release from these duties in July 1917. He was sent back to England in September and then returned to Canada.

This long military interlude in Price’s life had no negative effect, however, on the fortunes of Price Brothers; its assets were estimated at $19.5 million in 1919 (an increase of $1.4 million over the previous year) and the company recorded a registered capital of $10 million. The Kénogami plant had a daily output of 212 tons of paper, 90 tons of chemical pulp, and 178 tons of mechanical pulp, the one in Jonquière 34.55 tons of paper and 69 tons of mechanical pulp. The factory in Saint-Germain-de-Rimouski produced 10,000 tons of mechanical pulp per year, and the sawmills owned by Price Brothers at that time (in Batiscan, Montmagny, Cap-Saint-Ignace, Saint-Germain-de-Rimouski, Matane, and Lac-au-Saumon) had an annual output of 30 million feet of lumber, 80,000 railway ties, and several billion cedar shingles.

After a period of consolidation in the 1910s, Price Brothers entered a phase of expansion. In 1920 it increased its registered capital to $60 million. Its projects were huge: the construction of a hydroelectric station at La Grande Décharge of Lac Saint-Jean to supply power for a new pulp and paper mill it planned to build on land that in 1925 would become the town of Riverbend (Alma). Hence in 1920 Price became a minority shareholder (with one-quarter of the shares) in the Quebec Development Company Limited [see Benjamin Alexander Scott]; founded in 1913, its majority shareholder was James Buchanan Duke, president of the American Tobacco Company [see Sir Mortimer Barnett Davis]. Duke owned the water-power rights on Île Maligne and Price was to obtain, from the government of Louis-Alexandre Taschereau*, who had recently become premier of the province, the necessary permits that would, among other things, let them keep the water level at La Grande Décharge at its maximum height and develop the potential for hydroelectric power. This first step was ratified by an order in council on 7 Dec. 1922.

Price agreed he would transfer 2,850 shares in the Quebec Development Company Limited to Duke, and then buy back 5,950 shares in it for $855,000. In return, the company was to issue an initial bond series of $4 million and undertake the construction of the hydroelectric station, assuming 75 per cent of the cost, with the other 25 per cent to be paid by Price Brothers. It also agreed to supply electricity to the Price Brothers paper mills in the Saguenay region for some 20 years. The work was begun in 1923 and a second series of bonds, to the value of $12 million, had to be issued the following year. The shareholders adopted the corporate name of Duke-Price Power Company Limited, and this firm obtained letters patent in July 1924 with an authorized capital of $1.5 million. The Riverbend plant went into production and the hydroelectric station at Île Maligne began transmitting its first kilowatts in 1925, after the death of Price. In order to sell the electricity produced by this station, Duke-Price Power merged that year with the Aluminium Company of America and its Canadian subsidiary, the Aluminium Company of Canada Limited. These two companies would buy it out in 1926. This transaction would be the first setback in the fortunes of the Price empire, which would thus find its share in the partnership substantially reduced.

Along with his involvement in Price Brothers, Price had fully participated at the beginning of the 20th century in the endeavour to revive the economy of Quebec City. In 1903 he was elected president of the Quebec Chamber of Commerce. Since the late 1890s plans for rail connections had been on the drawing board, with a view to creating a railway terminus of national scale in the old capital. Besides the Great Northern Railway’s plan, which was already being carried out [see Richard Reid Dobell*], there were two others, those of the Quebec and James Bay Railway Company and the Trans-Canadian Railway Company. Price was a director of both corporations. Unfortunately, in comparison with the Grand Trunk and the Canadian Northern Railway, the proposals of the Quebec City bourgeoisie carried little political weight. The governments of Sir Wilfrid Laurier* and Simon-Napoléon Parent* lost interest in them. Laurier saw them as competing with his intention to construct a new transcontinental link that favoured a different route. As for Parent, he took so long to make up his mind that by 1906 not a single stretch of railway had been built. The projects would be taken over by the Canadian Northern Railway group.

Since 1900 Price had been a director of the Union Bank of Canada [see Andrew Thomson], and Price Brothers had their offices in its building, which had been renovated and enlarged in 1897. In 1908, when he became the bank’s vice-president, its balance sheet showed a profit. In the course of that year it opened eight new branches in Saskatchewan, one in Ontario, and one in British Columbia, and it paid the shareholders a dividend of seven per cent – nearly $222,500. Price was also a director of the Quebec Steamship Company, the Guaranteed Pure Milk Company of Quebec Limited, the Quebec Bridge Company, the Quebec Railway, Light and Power Company, Jeffery Hale’s Hospital, and the Prudential Trust Company Limited.

Early in the 20th century, Price had, moreover, embarked on a political career. He ran unsuccessfully as a Conservative in the riding of Rimouski in the federal general election of 1904. Four years later he made another attempt in Quebec West. The constituency had been held by his Liberal opponent, William Power, since the death in 1902 of his predecessor, Dobell, and indeed by the Liberals ever since Laurier’s first victory in 1896. The election campaign was bitterly contested. Like Rodolphe Forget*, Price was identified with the trusts and millionaire businessmen. His opponents accused him of not using the port infrastructure at Quebec, which he promised nonetheless to develop if elected. Price himself denounced the political inertia of Power in particular and of the federal Liberals in general, who, although they had held the riding for many years, had not managed to develop either a modern port or a railway terminus of national scale. Price won the election by 10 votes, following a judicial recount. His infrequent speeches in the House of Commons dealt with maritime issues (the construction of a building in the port of Vancouver), military matters (the enlargement of the Royal Military College of Canada), and railways (the administration of the Intercolonial Railway). From a man eager to put Quebec City back on the road to progress and prosperity, it was hardly a brilliant performance.

In the federal general election of 1911, Price ran in the same riding and faced the same opponent. Once again the Liberals accused him of being a millionaire who took no interest in the economic development of the old capital. He defended himself by pointing out that as an opposition mp his influence was limited. He believed, moreover, that commercial reciprocity with the United States would seriously hurt farmers, industrialists, and working people. The domestic market, developed by means of the National Policy [see Sir Samuel Leonard Tilley*], should, in his opinion, be preserved, as well as economic ties with the mother country, England. In his view, prosperity followed east-west, rather than north-south, lines. This profession of faith, at once Canadian and imperialistic, failed to win him the riding. Power obtained a majority of 91 votes and Price’s active political career was over.

Price died on 2 Oct. 1924. While he was in the lumber yard at the Kénogami plant with two engineers, examining a hole left by a cave-in, he had been swept into the Rivière aux Sables by a landslide. His body was found a week later. His sons John Herbert and Arthur Clifford, who were both in their early twenties, succeeded him at the helm of Price Brothers. Although they were responsible in 1929–30 for the construction of the first skyscraper in the old capital, they did not enjoy the financial success their father had. During the depression of the 1930s, Price Brothers was driven to the brink of bankruptcy, and the members of the founding family lost control of it. At the outset of the 21st century, a few of Price’s descendants continue to live in the Quebec City region, where they own an inn and two museums, as well as interests in the pulp and paper and lumber industries. What’s bred in the bone will come out in the flesh. In 2002 a few relics of the bygone days could still be found: the Price building in the historic quarter and the Price residence on Rue Grande Allée at Quebec, and the monument to William Price (Sir William’s grandfather) in Chicoutimi. But other bits of history have disappeared with the passage of time, including the Price Cup, which was awarded in 1911 to the winners of two races, one for sailboats and the other for motor boats. Like their founder, these contests had fitted both the tradition of the 19th century and the modernity of the 20th.

Information about Sir William Price’s activities as a businessman can be found in the Quebec Official Gazette, especially for the years 1899–1900, 1902, 1910, 1912, 1919–20, 1923–24, and in the Pulp and Paper Magazine of Canada (Gardenvale, Que.), specifically from 1905 to 1913 and in 1924. The most important source, however, is the Price Brothers fonds (P666) at ANQ-SLSJ (mfm. at ANQ-Q). Of particular interest are S1, SS2, 1.5–1.8; SS3, 20.7; SS7, SSS1, 36.4–36.16; S11, SS1, 283.1; SS2, 284; S14, SS1, SSS1, 288.3, 288.18.

ANQ-Q, CE301-S61, 25 janv. 1894. LAC, RG 150, Acc. 1992–93/166. Le Devoir, 3–4 oct. 1924, 28 avril 1926. Le Progrès du Golfe (Rimouski, Qué.), 7, 14, 21, 28 oct., 4 nov. 1904. Quebec Chronicle, 28, 30 Sept., 7–8, 13, 16, 18–19, 22–24, 27 Oct. 1908; 30 Aug., 6, 11, 16, 18, 21–22 Sept. 1911. La Semaine commerciale (Québec), 9 juill. 1897; 1er févr., 30 août 1901; 23 janv., 20 mars, 24 avril, 8 mai 1903; 9, 30 mars 1906; 27 nov. 1908; 1er janv., 3, 9 avril, 8 mai, 11 juin, 2 juill. 1909. Le Soleil, 6, 13, 20, 30 oct., 2 nov. 1908; 20, 22 sept. 1911; 10–11, 16, 25, 28 août 1914; 15, 18 févr., 19 avril 1919; 21 juin 1998; 4 oct. 2001. Jules Bélanger et al., Histoire de la Gaspésie (Montréal, 1981). Can., House of Commons, Debates, 1909–11. Canadian directory of parl. (Johnson). Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1912). J.-P. Charland et Jacques Saint-Pierre, Les pâtes et papiers au Québec, 1880–1980: technologies, travail et travailleurs (Québec, 1990). Cyclopædia of Canadian biog. (Rose and Charlesworth), vol.3. Directory, Quebec and Lévis, 1900–1, 1906–7. J.-C. Fortin et Antonio Lechasseur, Histoire du Bas-Saint-Laurent (Québec, 1993). Camil Girard et Normand Perron, Histoire du Saguenay–Lac-Saint-Jean (Québec, 1989). Histoire de la Côte-du-Sud, sous la dir. d’Alain Laberge (Québec, 1993). Histoire de la Côte-Nord, sous la dir. de Pierre Frenette (Québec, 1996). Histoire de Lévis-Lotbinière, sous la dir. de Roch Samson (Québec, 1996). Nicholson, CEF. Pierre Poulin, “Déclin portuaire et industrialisation: l’évolution de la bourgeoisie d’affaires de Québec à la fin du XIXe siècle et au début du XXe siècle” (mémoire de ma, univ. Laval, Québec, 1985). Prominent people of the province of Quebec, 1923–24 (Montreal, n.d.). Que., Statutes, 1900, c.73. Bérard Riverin, “La pulperie de Jonquière (1898–1902),” Saguenayensia (Chicoutimi, Qué.), 17 (1975): 94–100. Mason Wade, The French Canadians, 1760–1967 (rev. ed., 2v., Toronto, 1968).

Cite This Article

Jean Benoit, “PRICE, Sir WILLIAM,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 21, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/price_william_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/price_william_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | Jean Benoit |

| Title of Article: | PRICE, Sir WILLIAM |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2005 |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | February 21, 2026 |