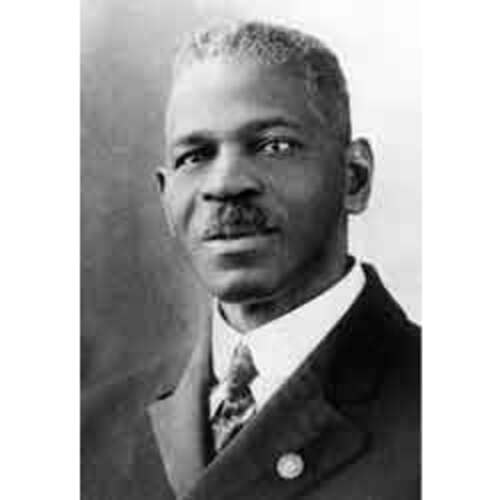

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

WHITE, WILLIAM ANDREW, Baptist clergyman and military chaplain; b. 16 June 1874 in King and Queen Court House, Va, son of James Andrew White and Isabella Waller; m. 28 June 1906 Izie Dora White in Truro, N.S., and they had 13 children; d. 9 Sept. 1936 in Halifax.

The son of former slaves, William Andrew White grew up in a remote area of northeastern Virginia. His hometown had been more or less destroyed in 1864, near the end of the Civil War, but with reconstruction came gradual improvement in the lives of the black inhabitants. By 1866 black churches, mostly Baptist, had begun to form in King and Queen County. As of 1872 eight black public schools were operating; by 1894 there was also a black high school. Little is known of White’s early years. In the 1890s he made his way to Baltimore, Md, where he became a member of the Union Baptist Church, and then to Washington, D.C., to attend Wayland Seminary, which had been preparing freedmen for the Baptist ministry since 1867. Among the faculty was Mary Helena Blackadar, an alumna of Acadia University, a Baptist institution of higher learning in Wolfville, N.S. Acadia had graduated its first African Canadian, Edwin Howard Borden, in 1892. It seems that Blackadar, who was well connected with the Baptist Convention of the Maritime Provinces, put White in touch with the superintendent of its Home Mission Board for Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island, and she wrote to her alma mater on his behalf. He was accepted by Acadia in 1899 and moved to Canada. Not only did he do well in his classes but the six-foot-four athlete also excelled on the sports field.

During the summer of 1902 White was supply minister at Cornwallis Street Baptist Church, Halifax, principal congregation of the African Baptist Association; both had been founded by Richard Preston*. While there, White made the acquaintance of the province’s first native-born black lawyer, James Robinson Johnston*, who was well on his way to becoming a leader in the African Canadian community. When White received a ba in 1903, the Baptist Convention of the Maritime Provinces ordained him its second black minister (Wellington Ney States* had been the first). He was immediately appointed the Home Mission Board’s general missionary to people of colour. He toured Nova Scotia’s black settlements and churches from Cape Breton Island to Yarmouth County, and along the way he established Second Baptist Church in New Glasgow. It was probably during one of these missionary circuits that he met and became engaged to Izie Dora White of Mill Village, which had a small but thriving population descended from slaves of the New England Planters who had settled Liverpool Township in pre-loyalist days.

White’s role as ordained missionary was undermined and ultimately derailed by tension between the white Baptist Convention and the African Baptist Association; the latter resented the intrusion of a convention minister just after it had appointed States as its own field missionary. With a view to maintaining good relations, the Home Mission Board decided to release White so that he could find a permanent post. He chose Zion Baptist in Truro, whose pulpit had fallen vacant in October 1904 when its pastor returned to the United States. Zion had been formed in 1896 by a secession of black people from the local Baptist congregation. Despite the fact that the black presence in the area dated back to its settlement by Scots-Irish American farmers in the 1760s [see Alexander McNutt*], racism had gained ground as the memory of slavery receded. During the second half of the 19th century segregation in Nova Scotia communities had become the norm, and the establishment of separate houses of worship was generally accepted as an enlightened example of progressive race relations and practical Christianity. White was no stranger to the fledgling church, having assisted there when he graduated from Acadia, and in May 1905 he was installed as its pastor. The following year he married 18-year-old Izie Dora, and they would have a large family, among whom was the internationally renowned contralto Portia May White*.

White was in his tenth year at Zion when World War I broke out in 1914. He championed the determination of men of colour to serve king and country. Although Colonel Samuel Hughes*, minister of militia and defence, declared that black Canadians should be allowed to enlist, those who tried to do so were often rejected by local battalion commanders [see Rankin Wheary*]. In mid 1916 a segregated, non-combatant unit, to be led by white officers, was authorized. Nearly 700 black men from across Canada (more than half of them Nova Scotians) volunteered for the No.2 Construction Battalion, Canadian Expeditionary Force. White, who helped lead recruitment efforts, became their chaplain and was made an honorary captain. He was part of the Canadian Chaplain Service [see John Macpherson Almond], but as a supernumerary he needed special permission to proceed overseas with the unit.

Some members of the battalion trained in Windsor, Ont., and the rest in Pictou, N.S., and later Truro. In March 1917 the unit embarked for England. They were attached to the Canadian Forestry Corps (Jura Group) and relegated to the status of “company” because they were about 300 men under strength. In May they were sent to eastern France, where they worked alongside white troops during logging and milling operations but were segregated the rest of the time. Their chaplain had a hard row to hoe: white soldiers would not accept his ministrations, even when they otherwise lacked the services of a clergyman. Nevertheless he was an unmitigated force for good across racial lines. Such were his courage, moral authority, and physical stature that he once interposed himself between his unit and a group of white men to avert a riot.

After the war the No.2 Construction Battalion was demobilized. In 1919 White, who had felt compelled to resign from his position at Zion in the spring of 1918, was called back to Cornwallis Street Baptist Church, which had been without a preacher for several months. As leader of the mother church he became more active and influential in the wider Baptist and Protestant community in the city. In 1915 he had replaced the murdered James Johnston as secretary (also styled clerk) of the African Baptist Association, a position in which James Alexander Ross Kinney substituted after White departed overseas. In 1922 he resumed his work with the organization, now called the African United Baptist Association, and would go on to become moderator from 1929 to 1931. He would be re-elected moderator in absentia just two days before his death. He was the first black clergyman to preach before the Baptist Convention and was a member of its ordination council. In addition he was appointed secretary of the Halifax and Dartmouth Ministerial Association in 1926. In the early 1930s he instigated monthly radio broadcasts of his worship services from Cornwallis Street, which were heard across Canada and in the northern United States, and he was proud to preside over the centenary of his church in 1932. Four years later his alma mater awarded him an honorary dd, just a few months before he succumbed to pneumonia resulting from acute ulcerative colitis.

William Andrew White has achieved almost mythic status since his death. Two documentary films about him have been produced: Captain of souls: Rev. William White (1999) and Honour before glory (2001). White’s legacy is important not only because he was, as historian Robin W. Winks says, “the universally recognized leader of the province’s Negroes regardless of faith or heritage,” but also because he was the first African Baptist to be fully accepted by the white clerical establishment, thanks in part to his university education. African American pastors had come and gone before him; few remained long, and fewer still made any appreciable impact. White was the exception: he came, saw, conquered – and stayed. He thus reversed the path taken by E. H. Borden, who had headed to the United States and fashioned a distinguished career in the ministry. However, given the parochialism and xenophobia of Nova Scotia’s blacks, the American-born White could never be a race leader in the same sense as his native-born contemporaries Johnston, States, and Kinney. Nevertheless he paved the way for another Acadia alumnus, William Pearly Oliver*, who succeeded him as pastor of the mother church, thus perpetuating for at least a generation de facto leadership by African Baptist ministers. “More than a pastor,” a contemporary of White’s eulogized, “he was the counsellor, arbitrator and authority for the entire colored population east of Montreal.” As such he was instrumental in bringing Nova Scotia’s black population into the 20th century, and he remains one of the most significant figures in the history of black Atlantic Canada.

The author acknowledges with most grateful thanks the assistance of Patricia Townsend, Archivist, Acadia Univ. (Wolfville, N.S.), in the preparation of this biography.

William Andrew White left neither a will nor an estate settlement case file. His overseas diaries, October 1917–December 1918, are held in the William Andrew White fonds (R15535-0-8) at LAC; if there were other journals, they are no longer extant. His wartime activities are well documented by military holdings at LAC, including the war diary and other records of the No.2 Construction Battalion (also known as the No.2 Canadian Construction Company); see the guide “Sources relating to units of the Canadian Expeditionary Force,” Canadian Forestry Corps, No.2 Canadian Construction Company: www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/discover/military-heritage/first-world-war/Documents/canadian%20forestry%20corps.pdf (consulted 21 Aug. 2015). See also the Canadian Chaplain Service records (R611-275-6) and corr. (R611-360-8, vol.4634, file R-MC-15) and White’s service file (RG 150, Acc. 1992–93/166, box 10307-29), all at LAC. White’s library and personal papers, which must have been voluminous, probably did not survive the death of his widow, who married in 1949 a younger brother of James Robinson Johnston and died in 1972.

Nova Scotia archival sources consulted include the records of Cornwallis Street United Baptist Church, the Home Mission Board of the United Baptist Convention of the Atlantic Provinces, and Wolfville United Baptist Church, all held at the Atlantic Baptist Arch., Acadia Univ.; the subject’s marriage and death registrations, accessible at NSA, “Nova Scotia hist. vital statistics,” Colchester County, 1906, and Halifax County, 1936: www.novascotiagenealogy.com (consulted 31 July 2015); and the Zion Baptist Church records (1905–18), held at Zion United Baptist Church, Truro (N.S.).

Acadian (Wolfville), 1903–34. Maritime Baptist (Saint John), 1905–36. E. S. Mason, “The late Rev W. A. White, D.D.: an appreciation,” Maritime Baptist, 16 Sept. 1936. Messenger and Visitor (Saint John), 1903–5. Truro Daily News, 1905–19. Wolfville Acadian, 1934–36. Acadia Athenaeum (Wolfville), 1903–36. Acadia Bull. (Wolfville), 1913–36 (esp. the obit. by G. C. Warren in v.23 (1936): 6–8, available online at openarchive.acadiau.ca/cdm/landingpage/collection/AAB). African Baptist Assoc. of N.S., Minutes (Halifax), 1903–36. J. G. Armstrong, “The unwelcome sacrifice: a black unit in the Canadian Expeditionary Force, 1917–19,” in Ethnic armies: polyethnic armed forces from the time of the Habsburgs to the age of the superpowers, ed. N. F. Dreisziger (Waterloo, Ont., 1990), 178–97. Baptist year book of the Maritime provinces of Canada … (Halifax, etc.), 1903–5; continued by United Baptist year book (Saint John), 1906–37. Captain of souls: Reverend William White, written and directed by Fern Levitt, produced by Peter Raymont and Lindalee Tracey (videorecording, Toronto, 1999). D. [W.] Crerar, Padres in no man’s land: Canadian chaplains and the Great War (Montreal and Kingston, Ont., 1995). S. F. Foyn, “The underside of glory: AfriCanadian enlistment in the Canadian Expeditionary Force, 1914–1917” (ma thesis, Univ. of Ottawa, 2000). Honour before glory, written, produced, and directed by Anthony Sherwood (videorecording, [Brampton, Ont.], 2001). B. B. Kaplan and Robert Willis, Land and heritage in the Virginia Tidewater: a history of King and Queen County ([Richmond, Va?], 1993). Bridglal Pachai, Beneath the clouds of the promised land: the survival of Nova Scotia’s blacks (2v., Halifax, 1987–91), 2 (1800–1989). C. W. Ruck, The black battalion, 1916–1920: Canada’s best kept military secret (rev. ed., Halifax, 1987). D. B. Sealey, Colored Zion: the history of Zion Baptist Church & the black community of Truro, Nova Scotia (Dartmouth, N.S., 2000). J. W. St G. Walker, “Race and recruitment in World War I: enlistment of visible minorities in the Canadian Expeditionary Force,” CHR, 70 (1989): 1–26. R. W. Winks, The blacks in Canada: a history (2nd ed., Montreal and Kingston, 1997).

Cite This Article

Barry Cahill, “WHITE, WILLIAM ANDREW,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 27, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/white_william_andrew_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/white_william_andrew_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Barry Cahill |

| Title of Article: | WHITE, WILLIAM ANDREW |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 2017 |

| Access Date: | April 27, 2025 |