![Charles Allan Smart

Date : [Vers 1950]

Source: https://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/3108623 Original title: Charles Allan Smart

Date : [Vers 1950]

Source: https://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/3108623](/bioimages/w600.14710.jpg)

Source: Link

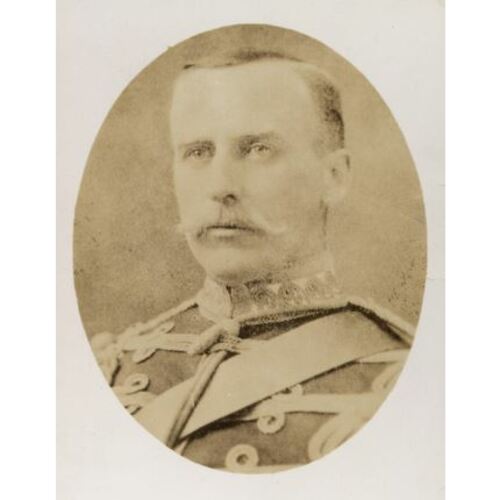

SMART, CHARLES ALLAN, businessman, militia and army officer, and politician; b. 23 March 1868 in Montreal, son of Robert Smart, a shoemaker, and Margaret Clark; m. there 28 June 1893 Ellen Maud McWood, and they had one daughter; d. 4 June 1937 in Westmount, Que.

Charles Smart grew up in Montreal in a family of hard-working Scottish immigrants. His father was from Aberdeen and his mother from Arbroath. He was educated in public schools and at the High School of Montreal. His first job, in 1881, was as a clerk for Alexander Buntin and Company (from 1883 Buntin, Boyd and Company) [see Alexander Buntin*], a stationery firm. After three years there, he switched to a dealer in oils, Tellier, Rothwell and Company, where he spent seven years. Next, he worked as a commercial traveller for the Dominion Bag Company Limited and advanced to the positions of manager and secretary. In 1906 he became a representative for the Consumers’ Cordage Company.

In 1898 Smart had joined the 6th Hussars, a militia cavalry regiment in the Eastern Townships. He was promptly commissioned a second lieutenant and assigned to the Clarenceville (Saint-Georges-de-Clarenceville) squadron. In August 1900, with a first-class certificate from the cavalry school in Toronto, he rose to lieutenant, and by 1902 he headed his squadron with the rank of major. The British general officer commanding the Canadian militia, Lord Dundonald [Cochrane] invited Smart to organize a new regiment, the 13th (Scottish) Light Dragoons. Trained cavalry officers were scarce. The officers Smart chose for his new regiment shared a characteristic that drew the attention of members of Sir Wilfrid Laurier*’s Liberal cabinet: five, like Smart himself, were active Conservatives. Sydney Arthur Fisher*, minister of agriculture and acting minister of militia and defence when Smart’s list of officers was submitted for approval, struck out the name of a poorly qualified candidate and reluctantly approved the rest. Dundonald, already furious at the government for its indifference to his preparations for the American invasion he believed was imminent, publicly denounced Fisher’s partisan meddling. He was hurriedly recalled to Britain.

Meanwhile, Smart, newly promoted lieutenant-colonel, devoted his leisure time to training his regiment. After two years, the 13th was highly regarded, and in 1907 Smart completed his term as commanding officer. He then retired to the reserve of officers and used his business experience to create, in 1906, the Smart Bag Company Limited, of which he was president and managing director. The firm produced jute and cotton sacks, tailors’ canvas, buckram, hessian, twines, and linings for shirt collars in a factory at 800 Mullins Street in Montreal. Soon Smart had additional factories in Toronto and Winnipeg and, after he was joined by James William Woods of Ottawa around 1913, Smart-Woods Limited built more factories, in Ottawa and Welland, Ont. Its product lines expanded to include tents, awnings, duck, and grey cloth.

Even before he launched his own business, Smart had belonged to the St Andrew’s Society, the Engineers’ Club, the Montreal Military Institute, the Caledonian Society, and the Carnarvon chapter of the Royal Arch Masons. A leading Presbyterian, he was a master of his masonic lodge, a Shriner, and a Knight Templar, as well as vice-president of the local branch of the Canadian Manufacturers’ Association. For recreation and business connections he belonged to the Beaconsfield and Westmount Golf clubs. Prosperity enabled the Smarts to move from their modest house on Sussex Street to the new town of Westmount. Local politics there was uncomplicated. The Westmount Municipal Association, composed of prominent residents, offered a slate of approved candidates who were routinely elected. In 1910 Smart became a councillor. Two years later, he easily defeated Liberal William Rutherford in the newly created provincial constituency of Westmount to become the riding’s first representative in the Legislative Assembly.

Having acquired experience in product distribution, Smart brought his skills to the marketing of seafood as president of the Maritime Fish Corporation Limited in 1910. By then he was president of the Canadian International Corporation Limited. Shrewd investments in Quebec-based mining operations raised him to the boards of several mining companies. In 1911 he was appointed a director of the Banque d’Hochelaga and would retain the post until the bank merged with the Banque Nationale in 1924. Nor did he neglect his military interests. Samuel Hughes*, named federal minister of militia and defence after the Conservative victory in 1911, was eager to recognize old friends and loyal Tories. Smart was both. Early in 1912 he took over the Eastern Townships Cavalry Brigade and, soon after his promotion to colonel, he led the Provisional Cavalry Division in the 1914 manoeuvres in Petawawa, Ont.

When the First World War broke out, there was no obvious need for cavalry on the Western Front. Requirements changed as Turkey prepared to attack British-occupied Egypt. Ottawa volunteered to send 12 regiments of mounted rifles. Hughes offered Smart command of the 2nd Canadian Mounted Rifles Brigade, with the 4th, 5th, and 6th regiments. Smart assembled his men at Valcartier, Que., and sailed for England in mid July 1915. By then, the Turks had retreated from Egypt, and Ottawa had abandoned the notion of fighting them. Instead, on 22 October, Smart and his brigade embarked for France to join the new Canadian Corps. The corps needed a third division of infantry, not more horsemen. Frustrated and powerless, Smart fell sick and insisted on being sent to convalesce at a Voluntary Aid Detachment Hospital in southern France. Meanwhile, his men became the nucleus of the new 8th Infantry Brigade, commanded by Brigadier-General Victor Arthur Seymour Williams*. After his recovery Smart returned to England on 1 Jan. 1916 to head the 15th Infantry Brigade, a reinforcement formation.

On 31 October Smart took charge of the Canadians training in Crowborough. In April 1917 he replaced the elderly Samuel Benfield Steele* as commander at Shorncliffe, where he remained until he was demobilized on 15 Dec. 1918. Although he was obviously Hughes’s protégé, two mentions in dispatches, a companionship in the Order of St Michael and St George awarded on 4 June 1917, and promotion to brigadier-general in 1918 suggest that he satisfied his superiors. However, leading men in training camps was an undistinguished way to spend a war, and his deep bitterness would soon be vented.

While Smart was overseas, Quebec Liberal premier Sir Lomer Gouin* presented motions in the assembly requesting that the indemnities of Westmount’s representative be paid in full despite his absence. In the provincial election of 22 May 1916, he ensured that the “gallant Colonel Smart” was elected by acclamation. When Smart again took his seat, he was greeted by loud applause. After Canadian troops rioted on 4 and 5 March 1919 in Kinmel Park camp in north Wales in frustration at the slow pace of demobilization and five men died in the violence, an astonished assembly heard Smart pour out his resentment against the Canadian overseas administration in England. He revived allegations about the influence of Lady Perley, wife of Sir George Halsey Perley, former head of the Ministry of Overseas Military Forces, which claimed that she had persuaded her husband to leave Canadians in the hands of unskilled English doctors and untrained volunteer nurses while wasting of millions of dollars. He described his commander in England, Lieutenant-General Sir Richard Ernest William Turner*, as a “weak man,” surrounded by incompetents of his own choosing.

Smart’s charges, familiar to those who had spent the war in the ministry overseas but unknown to most Canadians, were enthusiastically embraced by the Liberal opposition and by newspapers struggling back to their pre-war partisanship. Most of his victims, such as Turner and the director general of medical services, Major-General Gilbert Lafayette Foster, could only expostulate in private letters. Had Smart shared the discomforts of his soldiers or faced the enemy with them? questioned Foster. “No, he remained less than three months in France and as much of that time as he could was spent under the sheltering care of the Medical Service.” Sir Robert Laird Borden’s Union government benefited from a careful rebuttal by Sir Andrew Macphail, the official historian of Canada’s medical services. Few Canadians wanted to rehash wartime politics, least of all veterans who were full of contempt for generals who had stayed safely in England during the fighting.

Smart’s career now centred on politics and business. He kept his Westmount seat in the general elections of 1919 (which he won again by acclamation), 1923, 1927, 1931, and 1935. He spoke rarely in the assembly, intervening only during the annual budget debate or to represent the interests of manufacturers, veterans, and Westmount and neighbouring municipalities. When, in 1926, the legislature had to ratify the federal charter for the United Church of Canada, he tried in vain to persuade the Roman Catholic majority to protect Presbyterian interests. Ill health prevented him from running in 1936, but the new premier, Maurice Le Noblet Duplessis* of the Union Nationale, was an old friend who remembered that Smart had helped him when he was an inexperienced politician. Duplessis named him to the Legislative Council for Inkerman Division on 18 May 1937. Smart’s condition improved and he was even seen walking without his wife’s support; however, on 4 June he died suddenly in his Westmount home, before he could take his seat on the council. His ashes were buried in Mount Royal Cemetery in Outremont (Montreal). At his death his fellow politicians referred to him as a gentleman, yet had trouble remembering his legislative contributions. As a militia officer, he had sacrificed time, energy, and money to keep Canadians safe, although few of them had believed they were in any danger. During the war he had obviously pleased his superiors, but his later comments illustrate some of the internal political conflicts that had troubled the Canadian command.

BANQ-CAM, CE601-S66, 28 juin 1893; CE601-S121, 26 avril 1868. LAC, R2421-0-0. Gazette (Montreal), 9 June 1904, 15 March 1919, 5 June 1937. J. S. Bryce, “The making of Westmount, Quebec, 1870–1929: a study of landscape and community construction” (ma thesis, McGill Univ., Montreal, 1990). Can., Dept. of Militia and Defence, Militia list (Ottawa), 1898–1905. Canadian annual rev., 1917, 1919. Directory, Montreal, 1891–1937. Desmond Morton, Ministers and generals: politics and the Canadian militia, 1868–1904 (Toronto and Buffalo, N.Y., 1970); A peculiar kind of politics: Canada’s overseas ministry in the First World War (Toronto, 1982). Prominent people of the province of Quebec, 1923–24 (Montreal, n.d.). Que., Legislative Assembly, Debates, 1912–37. Québec, Assemblée Nationale, “Dictionnaire des parlementaires québécois depuis 1792”: www.assnat.qc.ca/fr/membres/notices/index.html (consulted 22 May 2013). Who’s who and why, 1914, 1915/16. Who’s who in Canada, 1922, 1923/24, 1925/26, 1928/29, 1930/31, 1934/35.

Cite This Article

Desmond Morton, “SMART, CHARLES ALLAN,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 26, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/smart_charles_allan_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/smart_charles_allan_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Desmond Morton |

| Title of Article: | SMART, CHARLES ALLAN |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2015 |

| Year of revision: | 2015 |

| Access Date: | December 26, 2025 |