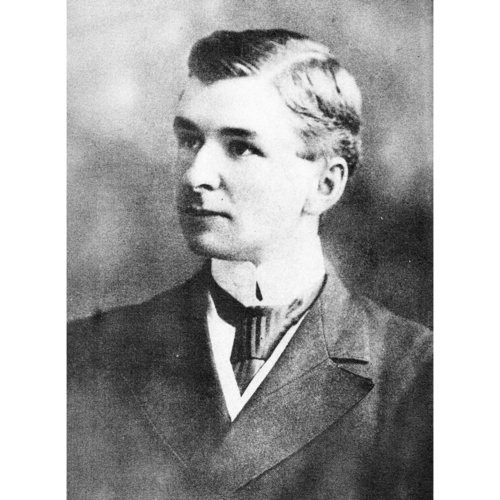

DUPLESSIS, MAURICE LE NOBLET (baptized Joseph-Maurice-Stanislas), lawyer and politician; b. 20 April 1890 in Trois-Rivières, Que., son of Nérée Le Noblet Duplessis and Berthe Genest; d. unmarried 7 Sept. 1959 in Schefferville, Que., and was buried in his hometown.

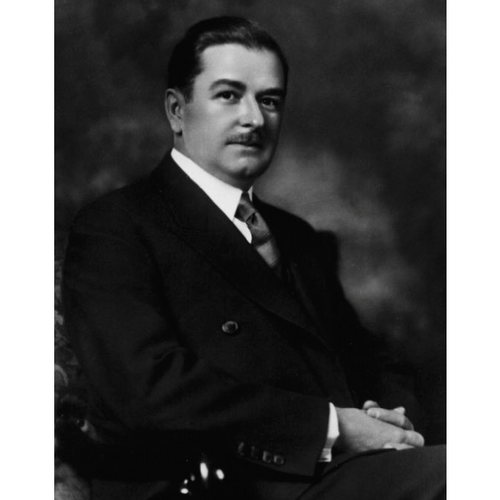

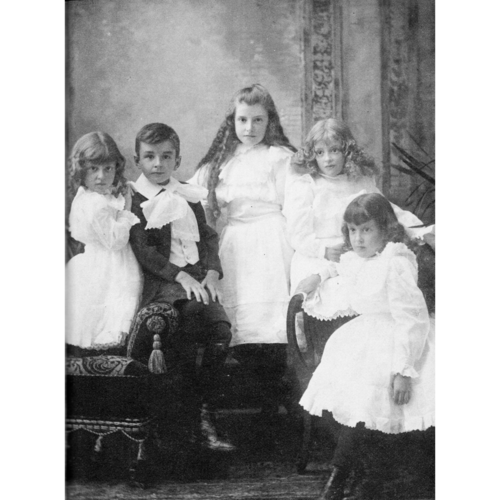

Maurice Le Noblet Duplessis, who would be called “the Chief” or Maurice Duplessis, was to devote his life to politics, following in the footsteps of his father, a Conservative mla for the riding of Saint-Maurice from 1886 to 1900, town councillor and mayor of Trois-Rivières, and later judge of the Superior Court. From early childhood, Maurice, who would have four sisters, Marguerite, Jeanne, Étiennette, and Gabrielle, was steeped in an atmosphere of religious and political conservatism. The ultramontane Bishop Louis-François Laflèche* gave advice to his father, whom Maurice sometimes accompanied on election campaigns and to the Legislative Assembly. He also witnessed meetings with prominent members of the Conservative Party in his family home.

In 1898 Maurice was a boarder at the Collège Notre-Dame in Côte-des-Neiges (Montreal), where he made the acquaintance of Brother André [Alfred Bessette*]. In 1902 he entered the Séminaire de Saint-Joseph des Trois-Rivières for classical studies. There he distinguished himself in versification, history, Greek, Latin, and English. Often standing first in his class, he won many prizes as well as debates. In 1910 he enrolled in the law faculty of the Université Laval in Montreal and articled in that city at a firm headed by two Bleu lawyers, Rodolphe Monty and Alfred Duranleau. In September 1913, shortly after graduating, he was called to the bar, and he took up his profession in Trois-Rivières with his partner Édouard Langlois, a former fellow student at the seminary, who would marry his sister Gabrielle. Léon Lamothe would join them later.

During his twenty-some years as a lawyer, Duplessis practised civil, municipal, parish, and educational law more than criminal law, and his clients were more often ordinary citizens than companies. Sometimes, however, he did represent industries, such as the Shawinigan Water and Power Company. As a lawyer, Duplessis made a name for himself and built up a network of clients who would be very useful to him when the time came to seek election to Quebec’s legislature.

In 1923 Duplessis ran in a provincial election under the Conservative banner in the riding of Trois-Rivières. On 5 February he was defeated by 284 votes, after a campaign in which he had presented himself as the candidate of Trois-Rivières and a defender of municipalities’ rights, a theme he would replay in the next campaign. He spent the following four years in a pre-electoral campaign, visiting many municipalities, tracking his opponent wherever he went, meeting constituents individually, remembering all their names. His win by a majority of 126 in the general election of 16 May 1927 put an end to 27 years of Liberal rule in the riding. He would be returned there in the next eight general elections, from 1931 to 1956. On 19 Jan. 1928 the novice mla delivered his first speech in the Legislative Assembly with the self-assurance of a party leader; he presented an overview of current politics, laying emphasis on the difficulties encountered by municipalities that were competing for industries, and on industrial development, which seemed to attract more attention than the progress of agriculture and small business. Along the way, he decried the disrespect for the religious character of Sunday, the rise in taxes, the lack of an inventory of forest resources, and the government’s delay in imposing an embargo on the export of electricity; as well, he demanded a reorganization of the provincial police force. He made a strong impression on the whole house, even his opponents. When Premier Louis-Alexandre Taschereau stood up to shake his hand at the end of the speech, he supposedly remarked, “Keep an eye on this young man, he will go far.” Duplessis took advantage of his early years in parliament to create a network of contacts in Quebec City among both his Conservative colleagues and some members of the Liberal government.

The election of 1927 had left the Conservatives with only nine mlas. During the party’s convention on 9 and 10 July 1929, its head, Arthur Sauvé*, whose leadership was challenged by the rank and file, resigned and was replaced by Camillien Houde, the member for Montréal-Sainte-Marie, who was acclaimed. Houde, who had just become mayor of Montreal, was a rising star. Duplessis knew that Houde would be too undisciplined to be anything other than a shooting star in the sky of the capital: he would wait his turn. The two men were to be rivals for more than a decade. In the general election of 24 Aug. 1931, held in the midst of the Great Depression, the Conservatives managed to add only two members to their caucus, despite getting a larger share of votes than in the previous election; even Houde lost his seat. He and Thomas Maher, an active Conservative supporter, wanted to contest the elections of 63 Liberal mlas. Duplessis, who had taken his riding by 41 votes, was one of the dissident members who did not want to risk having their own elections overturned, and he was criticized for his reluctance by his leader, Houde. Taschereau had the rules governing the judicial contesting of elections changed by legislation known as the Dillon act and frustrated the Conservative plan [see Henry George Carroll*]. Defeated in the Montreal mayoralty race on 4 April 1932, Houde resigned as leader of the Conservative Party on 19 September. On 7 November some Conservatives met in caucus and chose Duplessis as leader of the opposition over Houde’s hand-picked heir apparent, Charles-Ernest Gault.

Duplessis now began his ascent, thanks to his talent, experience, and determination, but also as a result of the circumstances, with the Liberals undermined by the wearing effect of being in power, by corruption, and by the economic crisis. He became leader of the Conservative Party at the convention held in Sherbrooke on 4 and 5 Oct. 1933, defeating, with 332 votes to 214, the federal mp Onésime Gagnon*; the latter was supported by Houde’s followers and federal and English-speaking Conservatives, while Duplessis depended, within the party, on the young advocates for provincial autonomy who recognized his leadership qualities. He would consolidate his base by rewarding those who championed him and punishing those who opposed him. This victory represented above all a vote of confidence in the man, who soon gave up his career as a lawyer. Duplessis argued his last case on 4 Jan. 1934 for the Shawinigan Water and Power Company. Until then, he had spoken out mainly in support of agricultural credit for farmers and of farming as a vocation in the province of Quebec, and he had criticized the Liberals’ leniency towards the trusts and abusive monopolies, especially the electric-power companies, thereby repeating a popular theme, but with no strong personal conviction. It was in this period that he began managing to translate his talent for reading public opinion into votes at the polls. He had to flesh out his program at a time when the province was sinking deeper into the depression.

From the outset of the decade, Roman Catholic intellectuals who were French Canadian nationalists had been seeking solutions to the crisis of capitalism, while avoiding socialism. In November 1933, ten of them, including Esdras Minville*, Philippe Hamel, Albert Rioux*, Alfred Charpentier*, René Chaloult, and Wilfrid Guérin, under the signature of the École Sociale Populaire [see Joseph-Papin Archambault*], published in Montreal the Programme de restauration sociale. A rather conservative document inspired by the social teachings of the Roman Catholic Church, especially corporatism, it proposed support for family farming and local industry, introduction of basic social legislation, and opposition to monopolies. This desire for reform also won over some members of the Liberal Party, which had been in power since 1897; they were disappointed by the impotence of the Taschereau government, which was weakened by allegations of corruption. In 1934 these dissidents founded the Action Libérale Nationale, under the leadership of Paul Gouin*, the son of former premier Sir Lomer Gouin*. Drawing inspiration from the Programme de restauration sociale, the new party promised, among other things, to give back to French Canadians control of their economy, encourage family farming through colonization and introduction of agricultural credit, carry out labour reforms, fight against the electric-power trusts, create a ministry of industry, and clean up politics.

As the 1935 election approached, Duplessis feared that the division within the opposition forces might let the Liberals hold onto power despite popular discontent. Eighteen days before the polls on 25 November, the formation of an alliance, the Union Nationale Duplessis–Gouin, was announced. The agreement on which it was based provided for ridings to be shared: 25 to 30 candidates for the Conservative Party and the rest (about 60) for the Action Libérale Nationale. The program adopted would be that of the latter group, which had many fine orators, but not a penny in the bank. In the event of a victory, the government would be led by Duplessis and most of the ministers would be chosen by Gouin from among the members of the Action Libérale Nationale. On election night, the Liberals held 48 seats, only six more than the two opposition parties, with 26 going to the Action Libérale Nationale and 16 to the Conservatives.

Although technically leader of the third party in the Legislative Assembly, Duplessis quickly pushed Gouin aside and took over what became the Union Nationale in 1936. His political style was unique. It would be said of Duplessis that he was a populist, because he cultivated his rural electoral base and expressed anti-elitist ideas when he spoke; that he was authoritarian, because he made arbitrary decisions; but also that he was generous, because he was known to come to the assistance of Liberal opponents who had become vulnerable. His influence over the opposition mlas and his popularity with the voters grew rapidly in the spring of 1936 when, convening the public accounts committee of the Legislative Assembly, he set himself up as a prosecutor in investigating the Taschereau regime.

The testimony given before this committee was damning and created a scandal. On 11 June the premier asked for the dissolution of the Legislative Assembly (which precipitated an election), submitted his resignation, and handed power over to Adélard Godbout. As reported in the Quebec City Action catholique that day, Duplessis reacted sarcastically: “Mr Speaker, there is no need for me to tell you that with a regime so dissolute, dissolution was imperative.” During a meeting held at the Windsor Hotel in Montreal on 17 June, Duplessis refused to renew the 1935 agreement. The past year had confirmed him as leader of the opposition forces. The break was finalized three days later in Sherbrooke during a special caucus meeting of 33 opposition mlas, when some stalwarts of the Action Libérale Nationale backed Duplessis. Gouin’s party was unable to get organized for the electoral contest. He himself so hesitated to stand that on 10 August he arrived at the registration office one hour after the closing time for nominations. The last of his supporters either declined to run or did so as independents. Not one of them was elected. During this campaign Duplessis posed as a reformer, committed himself to attacking the “moneyed powers,” suggested measures to clean up politics, and promised as well to rescue agriculture. But in the wake of the public accounts committee hearings, he especially emphasized the corruption of the Liberal regime. The Union Nationale published Le Catéchisme des électeurs d’après l’ouvrage de A. Gérin-Lajoie in Montreal, a pamphlet attributed to Louis Dupire, Louis Francœur, Roger Maillet, and Édouard Masson. Modelled on Catholic publications, it sought to extol the virtues of the party in opposition while stressing the shortcomings of the Liberal government.

In the election of 17 Aug. 1936 Duplessis’s party, which would be in power for more than 18 of the next 23 years, took 76 seats and 56.9 per cent of the vote, against 14 seats and 39.4 per cent for the Liberals, whose leader was personally defeated. In the fall the new premier called an emergency session of the Legislative Assembly. He declared from the outset, on 13 October, that he wanted to make agriculture “the fundamental basis of all the economic progress in [our] province,” and that he wanted “to develop colonization as a logical and indispensable complement of [its] agricultural development.” And so the Farm Credit Bureau came into being on 12 November, at a time when Quebec’s agriculture was suffering the severest crisis of its history. In the long run, this move would bring Duplessis the support of farmers, a basic factor in the longevity of the Union Nationale, given the over-representation of rural regions on the electoral map.

During this short session, Duplessis established an old-age pension program in conjunction with the federal government (something the Liberals had been rejecting since 1927, but had agreed to just before the election), and he introduced several amendments to the electoral law and the law on workplace accidents. Relieved of the reform wing of his party, he turned his back on radical policies such as nationalization of the electric-power companies and adopted a liberal approach that differed little from that of his predecessor. About corporatism he said not a word. One of the most striking measures of his first term of office was the Act respecting communistic propaganda (or Padlock Law), given royal assent in 1937, following a campaign launched by Cardinal Jean-Marie-Rodrigue Villeneuve* the year before. It was a measure intended to exploit the insecurity of the populace during that turbulent period. Applauded at first by the Catholic labour organizations, it would, in the end, constitute a threat to the trade-union movement: any place being used for the propagation of communism or Bolshevism could be condemned by the attorney general. The year 1937 set the tone for relations between the unions and Duplessis, whose most progressive step was the creation of the Fair Wage Board. It was not well received, however, by the trade-union movement, which preferred collective bargaining to the arbitration process set up to establish a minimum wage. In addition, Duplessis prohibited the closed shop (in which workers must belong to a designated union to be hired) and he exempted public works carried out for the government from the provisions of the Fair Wages Act and the Act respecting the extension of collective labour agreements (given royal assent in 1934). Moreover, he gave the government the right to revise agreements that had been extended by decree to an industrial sector. Last of all, that year Duplessis and his minister of labour, William Tremblay, intervened in the strike at the Dominion Textile Company Limited, ordering the workers to return to their jobs before negotiating. The government called in the provincial police in the shipyard workers’ strike in Sorel (Sorel-Tracy).

For Duplessis, the nationalization of electricity, or any other direct governmental intervention in the economy, was out of the question. It was mainly for this reason that he soon lost the confidence of Oscar Drouin, Joseph-Ernest Grégoire*, and Philippe Hamel, nationalist mlas and ministers from the Action Libérale Nationale whose concerns were with economic matters. Their resignations from the Union Nationale were followed by those of René Chaloult and Adolphe Marcoux. In June 1937 Chaloult and Marcoux, along with two members of the Legislative Council, formed the Parti National, which undertook to fulfil Duplessis’s unkept promises. The advent of Duplessis and the Union Nationale to power in the province represented primarily a changing of the guard. Economic liberalism would still be in the forefront, and in addition a social conservatism of a more definite ideological hue.

Much would be said about an alleged connivance between Duplessis and the Roman Catholic Church and even about the church’s undue influence over the state and vice versa. As a devout believer, the new premier went every Wednesday to Notre-Dame basilica in Quebec City to pray to St Joseph. After the death of his friend Brother André on 6 Jan. 1937, he had a mausoleum built in his memory. That year Duplessis introduced social measures compatible with the views of the church: assistance to needy mothers (but not unwed mothers and separated or divorced women), assistance to the blind, and renewed encouragement for colonization. He preferred the idea of charity to that of justice. In 1938, in his opening speech to the National Eucharistic Congress held in Quebec City, Duplessis explicitly rejected the principles of the French revolution and reiterated his profession of faith as a Catholic. He gave a ring to the archbishop of Quebec, Cardinal Villeneuve. The cardinal responded by emphasizing that this gesture signified the union of the temporal and the spiritual.

During his first term in office Duplessis witnessed a deterioration in the province’s economic situation as a result of the depression, and he attributed the mess in public finances to manoeuvres by Ottawa to restrict Quebec’s borrowing power. To put the unemployed back to work, he demanded that the federal government initiate a program of public works. He agreed to support a few of them himself, such as the completion of the Montreal Botanical Garden, which Brother Marie-Victorin [Conrad Kirouac*] had requested. Ottawa was also thinking of putting in place an unemployment-insurance scheme. When the royal commission on dominion–provincial relations (the Rowell–Sirois commission) was appointed [see Newton Wesley Rowell*; Joseph Sirois*], the Duplessis government put forward the basis of its autonomist thinking, grounded on the thesis articulated by judge Thomas-Jean-Jacques Loranger* in the 1880s: the Canadian confederation stemmed from a pact between the provinces, which the federal government had to honour. In taking this stance, Duplessis presented himself as Honoré Mercier*’s successor. Until World War II broke out, he would enjoy the support of his Ontario colleague, Premier Mitchell Frederick Hepburn.

For the time being, attention turned to the rising tensions in Europe. On 17 May 1939 Duplessis, with grace and dignity, welcomed King George VI and Queen Elizabeth, who were visiting North America to encourage support for their country in the coming conflict. Speaking in French in the chamber of the Legislative Council at the Parliament Buildings, he assured them of the loyalty of the French Canadian people. The king replied in the same language, praising the spirit of tolerance, brotherhood, and harmony between the two great “races” in the province of Quebec. Yet upon the outbreak of hostilities, Duplessis took a stand against participation in the war, thereby alienating English-speaking Conservative voters. On 23 Sept. 1939, shortly after World War II began, he called an election, hoping to catch the Liberal opposition off guard, with the idea that he could embarrass them by mention of the possibility of conscription. The strategy backfired when the Liberals guaranteed that no soldier would be forced to fight in Europe. Duplessis had to be defeated, they contended, or federal ministers Ernest Lapointe*, Pierre-Joseph-Arthur Cardin*, and Charles Gavan Power* would resign, leaving the field open to Ottawa conscriptionists. Moreover, because Duplessis refused to submit his scripts to federal censorship, he could not use the radio during the election campaign and relied instead on public meetings.

On 25 Oct. 1939 Godbout’s forces won a resounding victory: 70 seats and 54.1 per cent of the votes, against 15 seats and 39.1 per cent of the votes for the Union Nationale. From this defeat Duplessis learned two political lessons: to strengthen his electoral machine, and to do everything in his power to keep Quebec from finding itself financially at the mercy of the federal government. As leader of the opposition from 1939 to 1944, he often attacked the government’s fleeting impulses to exercise control over the provinces. The theme of provincial autonomy, foreshadowed in his stance on the Rowell–Sirois commission, would be central to his post-war speeches. In particular, he criticized Godbout for agreeing to the constitutional amendment that transferred unemployment insurance from provincial to federal jurisdiction, and opposed both the Rowell–Sirois report’s conclusions on centralizing direct taxes in Ottawa and putting them into effect for the duration of the war.

Duplessis also took advantage of his years in opposition to examine his conscience. There were more and more alarm signals. His fortunes were at their lowest ebb. His taste for alcohol had hurt his political performance, his reputation, and his health to the point that some people were questioning his leadership. He had already spent ten days in hospital in September 1929 following an automobile accident at Notre-Dame-du-Bon-Conseil (he had fallen asleep at the wheel). He underwent surgery for a strangulated hernia in March 1930 and again at the beginning of 1942. The first time, he was confined to bed for several months because of a haemorrhage. The second time, he spent four months in hospital recovering, his convalescence delayed by a bout of pneumonia. Refusing to admit defeat, he decided to stop drinking while there was still time. Diabetes would force him to slow down on several occasions, notably when he would be hospitalized in February 1952, and then in the course of his last term (1956–59).

During the early months of 1942, while Duplessis was in hospital, the province of Quebec was in a full-blown crisis over conscription. In January, Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King* had announced a Canada-wide plebiscite to release himself from his promise not to impose conscription for overseas service. For the most part, Union Nationale mlas took a stand against conscription. Duplessis was back in the Legislative Assembly five days before the vote on 27 April and he also recommended voting against it. However, the Ligue pour la Défense du Canada, led by such rising stars as André Laurendeau*, Jean Drapeau*, and Michel Chartrand*, had taken charge of the anti-conscription campaign. It was this organization that received most of the credit for the “no” victory (around 73 per cent of the vote) in the province of Quebec, a result diametrically opposite to that in the rest of Canada. The movement subsequently evolved into a political party, the Bloc Populaire Canadien, and threatened the Union Nationale’s monopoly of the nationalist vote.

Duplessis nonetheless remained a symbol of French Canadian nationalism, promising to defend the economic and political interests, as well as the traditions and identity, of the rural and Roman Catholic French province. He did this by presenting pressures for change, whether from the federal government, labour unions, or religious minorities, as outside influences harmful to the people. By flattering voters’ nationalism, he was able to preserve his alliance with the clergy, rural classes, and business community, and to advocate a model of development based on private initiative, even if financed by American capital.

Determined to climb back up and regain power, Duplessis fiercely attacked the reforms of the Godbout government. On 25 April 1940 he had echoed the opinion of Cardinal Villeneuve by opposing women’s suffrage, and in April 1943 he spoke out against the Act respecting compulsory school attendance for children from six to fourteen years of age. By summertime the three parties had embarked on a pre-election campaign, during which the Union Nationale and the Bloc Populaire Canadien vied for the support of the nationalist voters. In October 1943 Godbout announced the nationalization of the Beauharnois Light, Heat and Power Company and the Montreal Light, Heat and Power Consolidated, and in March 1944 the creation of the Quebec Hydro-Electric Commission (Hydro-Quebec), both of which were enacted into law in April. Having advocated control of monopolies several years earlier, Duplessis criticized the move mainly for its electioneering nature and the details of its implementation, and recalled that he himself had succeeded in forcing these companies to lower their rates without resorting to state ownership.

On 28 June 1944 Godbout called a general election for the summer. Duplessis emphasized the premier’s weak stand against Ottawa. On 8 August, benefiting from distortions in the electoral map and the presence of the Bloc Populaire Canadien (which, though appealing to the same nationalism as the Union Nationale, attracted Liberals happy with Godbout’s reforms but disappointed by his alignment with Ottawa), Duplessis was returned to power by a narrow margin, with 38 per cent of the votes and 48 seats. The Liberals, who had not been able to exploit the fear of conscription as they had done in 1939, won 37 seats, with 39.4 per cent of the vote. The war was coming to an end, and for this and other reasons the Bloc Populaire Canadien could not maintain the momentum of the anti-conscription campaign of 1942, and had to be satisfied with four seats for the 14.4 per cent of the votes cast for it.

So began an uninterrupted reign of more than 15 years for Duplessis. Unlike the time when he first rose to power in 1936, the province of Quebec was no longer in the grip of a depression. The war had boosted the economy and the increase in population in the post-war years sustained consumption. Despite the fact that the province was becoming industrialized, Duplessis continued to assert that agriculture was at the heart of its development. In 1945 he created the Bureau of Rural Electrification, which in ten years extended the distribution of electricity from 20 per cent of rural properties to nearly 90 per cent. The province had, however, become predominantly industrial and urban. Unlike Ontario, which would have more heavy and technologically based industries, much of Quebec’s economic growth would be founded on labour-intensive light industries and the extraction of natural resources that were in demand in the United States. The premier from Trois-Rivières encouraged foreign capital, especially American, to invest in Quebec, particularly in the north shore of the St Lawrence and Nouveau-Québec regions, boasting of its docile and hard-working labour force, its extremely low tax rates, and its minimal government intervention. His model for economic development, very similar to Taschereau’s, aimed at creating employment by attracting foreign investors. Paradoxically, this economic liberalism helped deprive French Canadians of control over their economy.

Convinced that the Catholic religion and the French language were the bedrock of the province of Quebec, and according paramount importance in his speeches to the established order – all of which put him in the good graces of the traditional nationalist elite circles, the clergy, and many of the local notables – the leader of the Union Nationale was still a social conservative. He distrusted the elites of the new generation, lay intellectuals, and union leaders, who advanced a concept of society different from his own. He was opposed to plans for public programs of social security, even to those adopted by most western governments of the day. At the beginning of 1945 he abolished the Quebec Health Insurance Commission, which had been set up two years earlier to study the institution of a health plan. In 1936, when his government had brought in the Act providing for the organization of a department of health, and again in 1946, when he created the Department of Social Welfare and of Youth to administer social allowances and organizations working with young people, he took care not to call into question the monopoly of the church and other private organizations in managing and delivering the services of hospitals, schools, and charitable undertakings. He would, however, provide them with an increasingly necessary legislative framework and financial support.

Duplessis was particularly opposed to the social programs put in place by the federal government. Shortly before the 1944 provincial election, King, who was getting ready to impose conscription, had announced the payment of family allowances. Duplessis denounced this project, which he considered contrary to the constitutional division of powers, while the church nearly convinced the prime minister that in the province of Quebec the allowances should be paid to fathers of families. The program took effect just in time for the 1945 federal election campaign, which the Liberals won.

Duplessis, who was personally in charge of intergovernmental relations, intensified his protests against what he considered threats by Ottawa to the autonomy of his province, demanding respect for the “confederation pact” of 1867. At the 1945 federal–provincial conference on post-war reconstruction, he insisted on the provinces’ right to tax personal and corporate incomes, estates, and gasoline. In 1947 the province ended its participation in wartime fiscal arrangements, as did Ontario, on the initiative of his counterpart, George Alexander Drew*. Ontario would not rejoin the agreement among the English-speaking provinces until 1952.

The fight against federal encroachment was not Duplessis’s only battle. On 4 Dec. 1946 he had the liquor licence of restaurateur Frank Roncarelli cancelled. A Jehovah’s Witness, he was posting bail for his co-religionists arrested for various infractions of municipal regulations; once released, they resumed their campaign against the Roman Catholic Church, much to the annoyance of clergy and the public. Roncarelli launched a suit against Duplessis that would end in a Supreme Court judgement on 27 Jan. 1959 in the restaurateur’s favour, but not without enhancing the Chief’s popularity. On 16 Feb. 1948 the provincial police invoked the Padlock Law to close the premises of the Labor-Progressive Party’s Montreal weekly, Le Combat. The Supreme Court would declare this legislation unconstitutional on 8 March 1957, putting an end to Duplessis’s crusade against the communists [see Francis Reginald Scott*]. The premier would, however, benefit until the end of his term in office from the favourable political fallout of a related matter that touched the sensibilities of Catholics and anti-communists: the Polish treasures from Wawel Castle in Kraków that had been kept out of Nazi hands. In 1948 Duplessis had them brought to the Musée de la Province in Quebec City, and he steadfastly refused to turn them over to the Polish communist government.

On 21 Jan. 1948 Duplessis announced that the province of Quebec had adopted the fleur-de-lys, which would henceforth fly on the flagstaff of the Parliament Buildings as a symbol of Quebec’s distinct identity. This move complemented the Liberals’ adoption, on 9 Dec. 1939, of a coat of arms and the motto Je me souviens. The raising of the flag was soon followed, on 9 June 1948, by the launching of another provincial election. Houde, once more mayor of Montreal and now reconciled with Duplessis, participated energetically in the Union Nationale’s campaign, carried out under the slogan: “The Liberals give to foreigners, Duplessis gives to his province.” (Duplessis’s reconciliation with Houde had come in 1944, when the latter had been hailed by the crowds after being interned for resisting conscription.) The theme of autonomy, as well as the effects of the Union Nationale’s patronage system – the promise of governmental favours to only those voters and businessmen who supported the Union Nationale – contributed to a resounding victory on 28 July 1948. The Union Nationale won 82 seats with 51.2 per cent of the vote, while the Liberals, with 36.2 per cent, took only eight. The Bloc Populaire Canadien had disbanded, but the Union des Électeurs, which preached the doctrines of Social Credit, got 9.2 per cent of the vote. This was the last election for Godbout, who lost the riding of L’Islet and would be appointed to the Senate by Louis-Stephen St-Laurent*, the new prime minister.

The term of office that lasted from 1948 to 1952 was marked by tensions in labour relations and by the appearance of serious opposition to the Duplessis regime. On 9 Aug. 1948 a group of artists, mainly from the visual arts, with Paul-Émile Borduas as their head, launched in Montreal their published collection Refus global, in which they denounced the traditionalism of Quebec society and its resistance to progress. Other centres of criticism would link the Duplessis regime’s conservatism to the social, educational, economic, and political backwardness of the province. These included the Montreal journal Cité libre, founded in 1950 by Gérard Pelletier* and Pierre Elliott Trudeau*; the École des Sciences Sociales, Politiques et Économiques of the Université Laval in Quebec City, founded in 1938 on the initiative of Father Georges-Henri Lévesque*; the Montreal newspaper Le Devoir, edited since 1947 by Gérard Filion*, whose editorial team included André Laurendeau; and Radio-Canada (the French-language network of the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation), which offered a platform for Duplessis’s detractors. Without a leader in parliament from 1949 to 1953, except for an acting head, George Carlyle Marler*, from July 1949 to May 1950, the Liberal opposition could not take advantage of the Union Nationale government’s weaknesses. All these adversaries helped portray the Duplessis regime, in a none-too-subtle manner, as a period of “great darkness.”

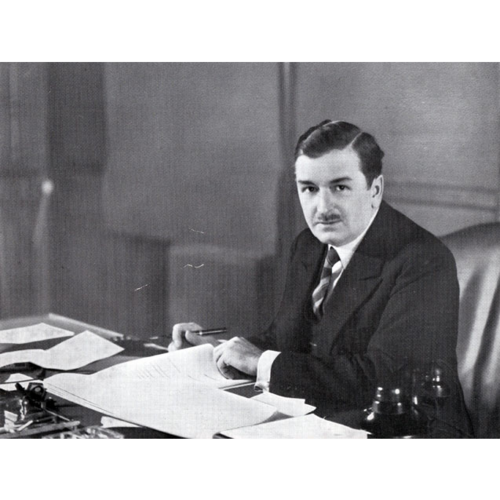

For Duplessis, politics was more a matter of favours than rights. His main objective was to stay in power. He dominated his party, whose members worshipped him. All could express their opinions at cabinet meetings, but he trusted only his own. He had his tried-and-true followers and those whom he kept on for reasons of electoral opportunism. In the house he whispered answers to them, or interrupted them, answering in their stead. On 16 June 1958 Le Devoir would report that he had silenced Antoine Rivard* in Baie-Comeau by saying, “Keep quiet, keep quiet.… Let me do it!” Sometimes he would intervene directly in the affairs of a ministry, overriding the authority of the minister in charge. During his first term of office, for example, he had taken personal charge of contracts for roads. In his political biography The Chief, published in Montreal in 1963, journalist Leslie Roberts would write: “As Premier, Maurice Duplessis was the government of Quebec.” He had a network of personal informers throughout the province.

By restricting the freedom of trade unions through legislation, by making the Labour Relations Board biased through his appointments, and by intervening personally in labour disputes – often by using the provincial police – Duplessis alienated the working class in the province of Quebec. Before 1952 such actions would not have significantly affected his popularity in largely working-class ridings. (In 1953, to counter the negative effects among working people, Duplessis would amend the electoral law to make it easier to manipulate the urban vote. The voters’ lists would be drawn up by a single enumerator, appointed by the Union Nationale.) Duplessis had some success in attacking the most militant trade unions to maintain social peace that he considered essential to economic progress. Indeed, between 1945 and 1959, Quebec had only half as many strike days as Ontario did. To achieve his purpose, Duplessis often resorted to the provincial police, as he had done in Sorel in 1937 and Lachute in 1947. During the strike at Ayers Limited in Lachute, Duplessis had three militant trade unionists arrested, including Madeleine Parent*, who was charged with “seditious conspiracy.” Her trial lasted three months.

On 19 Jan. 1949, the minister of labour, Antonio Barrette*, introduced Bill 5, proposing to revise the labour laws into a labour code that Duplessis had already had drawn up without consulting his minister. Members of the clergy, some intellectuals, and all left-wing groups opposed this legislation. The government’s intention was clear: to restrict the trade unions’ right to organize and to strike, and to confer discretionary powers on the Labour Relations Board. The bill provoked an outcry among the unions, which refused to discuss it, mobilized against its adoption, and demanded it be scrapped. On 9 February Duplessis withdrew it, but he would return to the issue in the 1950s with piecemeal legislative amendments retroactive to 1944.

For the time being, the unions were emboldened by this retreat of the premier, who would soon be confronted with a historic labour dispute. Le Devoir had just published a series of articles on the ravages of asbestosis, a disease affecting asbestos miners. A few weeks later, a strike broke out at Asbestos and at Thetford Mines. The workers called for higher wages, a healthier workplace, and automatic union dues check-off. They also wanted a voice in management, one of the recent demands made by the Catholic unions. Duplessis had no intention of letting the workers oppose employers’ proprietary rights with this new principle of labour relations.

This strike became a symbol of two things: Duplessis’s fight on the side of the employers against the unions, but also the appearance of cracks in the alliance between his regime and the Roman Catholic Church. As a result of divisions between the conservative and progressive members of the clergy, including the bishops, the 5,000 striking asbestos workers enjoyed the moral and material support of many priests, including Archbishop Joseph Charbonneau of Montreal. In addition, there was the chorus of protests from the premier’s usual opponents. The strike, which was illegal, dragged on from 14 Feb. to 1 July 1949. It was marked by clashes between the strikers and the provincial police. Archbishop Maurice Roy* of Quebec was brought in as a mediator to settle the dispute, which ended with minor gains for the workers. They were given no voice in management and no steps were taken to control asbestos dust. From then on the distinction between the Catholic unions and the international unions became purely theoretical, as the textile workers’ strikes in Louiseville, Salaberry-de-Valleyfield, and Montreal in 1952 showed.

On 16 July 1952 the Union Nationale was re-elected with a very comfortable, though considerably reduced, majority, its share of the vote remaining at 50.5 per cent, while that of the Liberals rose to 45.8 per cent. The government in its new term of office, which would last from 1952 to 1956 and be dominated by the question of federal–provincial relations, began with 68 members and faced 23 in the opposition. Georges-Émile Lapalme*, head of the Liberals since 1950, had lost in his constituency and had to wait for a by-election in 1953 before he could take his seat as opposition leader.

Quebec and Ontario no longer received annual payments under the tax-rental program because they had withdrawn in 1947 from the fiscal agreements negotiated during the war. In 1952, when the formula for calculating these payments was amended, Ontario re-entered the arrangement. Since Duplessis, once more, refused to do so, Quebec found itself alone in maintaining an autonomist stance within the Canadian confederation. In December he announced that he would no longer accept federal grants to universities (initiated in October 1951 as a result of the royal commission on national development in the arts, letters, and sciences, or Massey–Lévesque commission, of 1949–51) because he considered this program the beginning of the federal government’s invasion into the field of education. At the end of 1952 Duplessis thus found himself in an awkward political position: his two refusals were costing the province millions of dollars.

By entrusting the royal commission of inquiry on constitutional problems, created on 12 Feb. 1953, to his old friend judge Thomas Tremblay, Duplessis hoped to achieve a balance of power with Ottawa by reaffirming the fiscal autonomy of his province, to give it some financial leeway. The commission’s hearings revealed that his standing on principle had considerable support, even from his political opponents. Taking advantage of this enthusiasm, he announced on 14 Jan. 1954 that a provincial tax amounting to 15 per cent of the federal tax would be imposed, and demanded that the latter be reduced by this percentage. A compromise was negotiated with Prime Minister St-Laurent, who spoke about it in the House of Commons on 17 Jan. 1955. Following two federal–provincial conferences held later that year, on 24 Feb. 1956 Duplessis announced an agreement on the new revenue-sharing formula: provinces not participating in the fiscal agreements would be allowed to have a reduction of up to 10 per cent of the federal tax on personal incomes, which would enable Quebec to keep its tax. St-Laurent had abandoned the Rowell–Sirois commission’s objective of centralizing financial resources in the hands of the federal government. Thus Duplessis was able to set aside the Tremblay report, which had been submitted a few days earlier; its conclusions went farther than he had wished, especially with respect to the province’s assumption of social programs and to educational reform.

In the field of labour relations, Duplessis had got the powers of the Labour Relations Board amended in 1954 through the adoption of Bills 19 and 20, which gave it the authority to refuse certification to unions whose executives included communists and to those favouring strikes in public services. It was a move that brought union members out into the streets once more. This time, unlike the occasion in 1949, Duplessis did not flinch. The episode – and the 1957 seven-month strike in Murdochville, which was marked by confrontations between workers and police – showed that nothing had changed between Duplessis and organized labour.

Another matter sullied the Chief’s last years: the highly controversial conviction of the prospector Wilbert Coffin for the murder of three American hunters in 1953. Duplessis challenged the attempt by the federal minister of justice, Stuart Sinclair Garson*, to have the Supreme Court intervene in the case. He considered this action an infringement on provincial authority in the field of the administration of justice. In any event Coffin was hanged on 10 Feb. 1956, but in the eyes of those who continued to protest his innocence in the years ahead, Duplessis was his executioner.

Despite these controversies, Duplessis was ready to go to the polls in 1956. Armed with a work by the nationalist historian Robert Rumilly*, Quinze années de réalisations: les faits parlent, published that year in Montreal, he boasted not only about his victory over federal centralization, but also about his accomplishments, including amendments to the Youth Protection Schools Act (1951), the Act respecting the regulation of rentals (1951), the founding of the Université de Sherbrooke (1954), and the establishment of the Quebec Agricultural Marketing Board (1956). On 20 June 1956 he and his party were re-elected with a slightly higher majority: 72 seats against 20 for the opposition. With 44.9 per cent of the vote, compared to 51.8 per cent for the Union Nationale, the Liberals were forced to recognize that they had been badly served by their pro-federal position in the debate on provincial autonomy. However, this election ushered in a period of disfavour, indeed decline, for Duplessis and his party, who would propose nothing new apart from an increase in prospecting in the Nouveau-Québec region to the benefit of American companies that would pay meagre royalties to the province.

The electoral methods used by Duplessis were brought to light in July 1956 by Abbés Gérard Dion* and Louis O’Neill*. In an article originally intended for the clergy but later widely disseminated (notably by Le Devoir on 14 Aug. 1956 under the title “L’immoralité politique dans la province de Quebec”), they accused the Duplessis regime of corrupting the electoral and political systems, extorting money from businesses and entrepreneurs, stealing the votes of some voters, and buying the tacit consent of the clergy by supporting its charitable works and playing the card of anti-communism. The eruption of the natural-gas scandal in June 1958 proved that Duplessis was beginning to lose control of his troops. Several ministers in his government were said to have purchased blocks of shares in the Quebec Natural Gas Corporation before the sale of the gas network was made public, and thereby becoming guilty of insider trading. The affair would drag on past the end of the Union Nationale government. The commission under judge Élie Salvas, established in 1960 by the government of Jean Lesage* to investigate the scandal, would also uncover the system of government purchasing controlled for the benefit of the Union Nationale by Gérald Martineau and Joseph-Damase Bégin*, respectively then a legislative councillor and a minister.

During the natural-gas scandal, Guy Lamarche, a journalist at Le Devoir, was barred from attending one of Duplessis’s press conferences. The premier was well aware of the power of the press. For this reason he was judicious in awarding government advertising contracts; as a result, even Liberal newspapers treated him with comparative moderation. Duplessis quite liked talking to journalists, and rewarding them, as long as they said good things about his administration. Television did not, however, show him to advantage, so he preferred radio.

Concerned to establish relations within the new federal government, and desiring to take revenge on the Liberals, Duplessis had discreetly extended his support and his party’s resources to the Progressive Conservatives of John George Diefenbaker* in the federal elections of June 1957 and March 1958, thereby contributing to their victory. In May 1958 Lesage, an mp and former federal Liberal cabinet minister, became leader of the Quebec Liberal Party, replacing Lapalme, who would stay on as leader of the opposition until 1960.

Duplessis, with the characteristic style that so pleased voters, declared on 1 June 1959, according to his biographer Robert Rumilly, “No one loves the province of Quebec more than the man who is speaking to you.” Indeed, Duplessis cultivated his populist image, both in his appearance and by his attitude. On 3 Sept. 1959, after visiting iron mines on the north shore of the St Lawrence region, the man who had been premier for more than 15 consecutive years suffered a cerebral haemorrhage in Schefferville, in a cottage belonging to the Iron Ore Company of Canada. He died in the very early hours of 7 September, Labour Day. He was succeeded by his heir apparent, Paul Sauvé, who prepared for an election campaign on the theme of change. But Sauvé himself died on 2 Jan. 1960, at the end of what the press dubbed the “100-day revolution.” It was Antonio Barrette who led the ranks of the Union Nationale to defeat at the hands of Lesage’s Liberals on 22 June 1960.

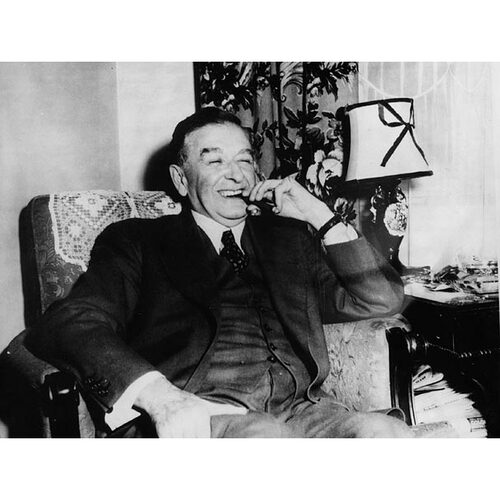

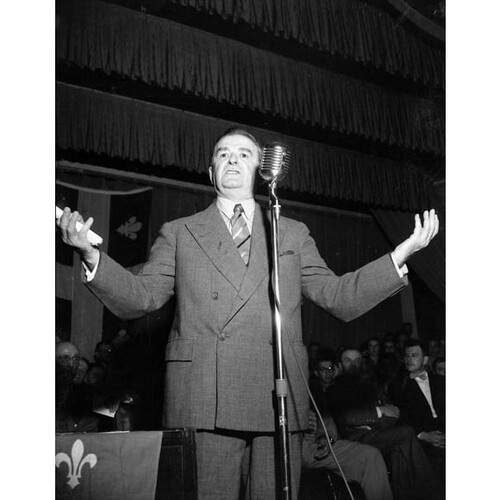

Duplessis will go down in history as a man of extraordinary intelligence and memory, with an exceptional political instinct. Of average height, he had a full head of hair until the end of his life, and a prominent nose that was much caricatured. His physical appearance was ordinary. He dressed plainly, but was always well groomed. To avoid tarnishing his image as a man of the people, he never wore conspicuous hats. For the same reason, he never boasted about his reading. He stood out mainly because of his personality and his frank manner of speaking. A fearsome debater, his diction nevertheless left much to be desired. Yet he was argumentative and quick-witted. He had a gift for repartee and puns, and liked to ridicule his opponents: for example, before the public accounts committee he attacked the spending of Irénée Vautrin, the minister of colonization, game, and fisheries in Taschereau’s government, after he asked to be reimbursed for the cost of his work pants, and Duplessis thereby immortalized the legendary “trousers of Vautrin.” Because he was a populist, his detractors were apt to call him a demagogue. Duplessis showed no mercy to his opponents, whose weaknesses he quickly spotted, but he could be magnanimous when he was in a position of strength. With the exception of Pierre Gravel, the curé at Boischatel, Duplessis had more accomplices than friends. But he showed almost a father’s love for Paul Sauvé and confided in the Montreal Gazette’s parliamentary correspondent, Abel Vineberg. Among his most loyal colleagues were Auréa Cloutier, his long-time private secretary; Gérald Martineau, the treasurer of the Union Nationale; Joseph-Damase Bégin, his chief organizer; Émile Bouvier, a Jesuit and professor of industrial relations who tended to favour employers; and Hilaire Beauregard, assistant director and later director of the provincial police. Totally involved in politics, Duplessis had few pastimes other than his interest in music and World Series baseball. Although he did not marry, he had a number of female companions. Never much attached to material goods, he collected the works of Canadian and Quebec painters that were given to him as presents.

A man of his generation, who drew on traditional values and on themes familiar to rural people despite the growing industrialization and urbanization of his province, Duplessis boasted that he led the only Catholic government in North America. As late as June 1956, according to Émilien Lafrance in Nous avons connu Duplessis, a work published in Montreal in 1977, he had declared, “A vote for the Union Nationale is a vote for your religious and Catholic faith.” The province of Quebec is indebted to him for the building of all kinds of infrastructure (roads, schools, hospitals, electric-power stations, and transmission lines to serve the whole province), the opening of the Chibougamau region and the north shore of the St Lawrence, and the industrial development of the Lac-Saint-Jean area. Under his government the province’s economic prosperity was ensured by spin-offs from mining (iron, asbestos) and by the manufacturing sector, as well as aluminum plants and chemical factories.

Socially and politically, Duplessis’s repressive labour policy and dishonest electoral methods led to more and more protests, both within the province and without. His system of patronage, a mix of favouritism and corruption, meant that it was necessary to vote “the right way” to benefit from the government’s largesse. He used in particular the private bills committee, which he chaired, to punish the enemies of his regime and reward its friends.

Duplessis had a minimalist view of the state. He ran the province economically by keeping the systems of education, health, and social services in the hands of under-financed religious communities. To make the most of federal funding, he had no hesitation in entrusting a large number of orphans to institutions for the mentally ill. The fact that the scandal of “Duplessis orphans” did not erupt until several decades later shows that his actions reflected some of the traditional values of his time.

Duplessis offered a vision of the autonomy of the province of Quebec that was criticized by his opponents, as well as by the generation that would experience the Quiet Revolution. He sought to preserve the liberal economic model that had been in place from the beginning of the 20th century. Since he refused to use the province’s powers to undertake reforms, this autonomy was described as purely defensive. His nationalism was also disputed, given that he was holding back the development of the province by handing over its resources to foreign investors on terms advantageous to them, though he himself had denounced this policy when it was pursued by his predecessors.

For the generation who knew him, Maurice Le Noblet Duplessis was a controversial figure, adulated by some, held in contempt by others. During the Quiet Revolution, his years in power were referred to as the “great darkness” and his political style as “Duplessism” or “partitocracy,” until with greater objectivity historians passed a more balanced judgement on the man and his work. In subsequent re-evaluations, his defence of provincial powers of taxation and his refusal to transfer constitutional jurisdiction in the field of pensions to the federal government have been acknowledged to have preserved, for future governments, Quebec’s capacity to act. As well, more discriminating comparisons have shown that the patronage and favouritism displayed by the Duplessis regime were not exceptional and were even common practice (although not in so systematic a way) in the political mores of other North American states.

The principal manuscript sources concerning the life and work of Maurice Le Noblet Duplessis can be found at the Arch. du Séminaire Saint-Joseph de Trois-Rivières, Que., 0019 (fonds Maurice L. Duplessis), the institution where he did some of his studies. This collection provides evidence mostly for his political career between 1927 and 1959. Before being made available to the public, this fonds was held for 30 years by the Société des amis de Maurice L. Duplessis Inc. Auréa Cloutier, Duplessis’s private secretary even before his political debut, assumed responsibility for its classification. She allowed three of his biographers, Robert Rumilly, Conrad Black, and Bernard Saint-Aubin, access to the fonds. Moreover, nine rolls of microfilm, containing copies made by Black, can be found at the Bibliothèque et Arch. Nationales du Québec, at the Centre d’arch. de la Mauricie et du Centre-du-Québec (Trois-Rivières) and the Centre d’arch. de Québec (where the fonds Maurice Duplessis are numbered respectively ZC9 and ZC44), and at York Univ. Libraries, Arch. and Special Coll. (Toronto), F0303 (Maurice Duplessis fonds). The Univ. of Windsor Arch. (Windsor, Ont.) also holds material on microfilm: 96-024 (Maurice Duplessis fonds).

Beginning with his contemporaries, the earliest authors to study Duplessis’s life and career had difficulty in remaining neutral. Among the printed sources there are, first of all, memoirs: Antonio Barrette, Mémoires (Montréal, 1966); René Chaloult, Mémoires politiques (Montréal, 1969); G.-É. Lapalme, Mémoires (3v., [Montréal], 1969–73); and Gérard Pelletier, Souvenirs (3v., Montréal, 1983–92). Among the biographies, the following two, written by journalists, are hostile to him: Pierre Laporte, The true face of Duplessis, trans. Richard Daignault (Montréal, 1960), and Leslie Roberts, The chief, a political biography of Maurice Duplessis (Toronto, 1963). In contrast, Robert Rumilly, who many times supported him in public, is indulgent towards him in Maurice Duplessis et son temps (2v., Montréal, 1973). Even though the first part of the biography he devoted to him was inspired by his master’s thesis in history, Conrad Black finds it hard to conceal his fondness for his subject in Duplessis (Toronto, 1977) and Render unto Caesar: the life and legacy of Maurice Duplessis ([rev.ed.], Toronto, 1998). Finally, one had to wait for Bernard Saint-Aubin, Duplessis et son époque (Montréal, 1979), to learn that Duplessis was “neither a god nor a demon.”

The following work is useful for those seeking an introduction to the various historical interpretations: Duplessis: entre la grande noirceur et la société libérale, sous la dir. d’A.-G. Gagnon et Michel Sarra-Bournet (Montréal, 1997). Finally, many political science and sociological studies about Duplessis’s society and regime, including countless contemporary accounts, have been published. They can be found by consulting Michel Lévesque, L’Union nationale: bibliographie (Québec, 1988).

Bibliothèque et Arch. Nationales du Québec, Centre d’arch. de la Mauricie et du Centre-du-Québec, CE401-S48, 21 avril 1890. La Patrie (Montréal), 8 sept. 1959.

Cite This Article

Michel Sarra-Bournet, “DUPLESSIS, MAURICE LE NOBLET,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 18, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 2, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/duplessis_maurice_le_noblet_18E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/duplessis_maurice_le_noblet_18E.html |

| Author of Article: | Michel Sarra-Bournet |

| Title of Article: | DUPLESSIS, MAURICE LE NOBLET |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 18 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2009 |

| Year of revision: | 2019 |

| Access Date: | January 2, 2026 |