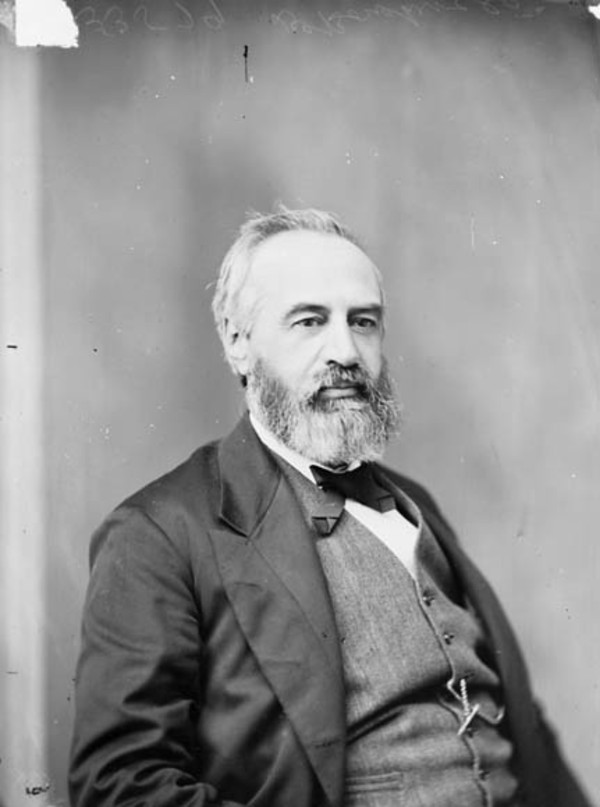

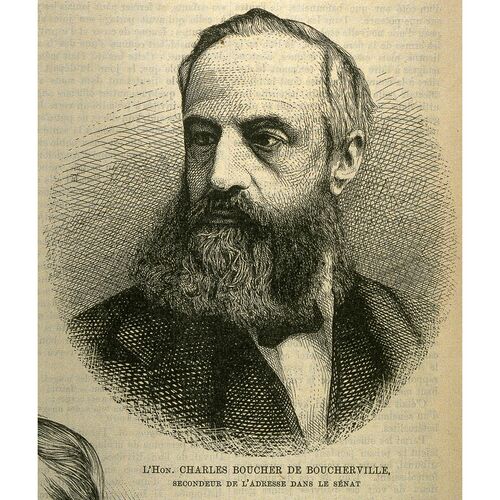

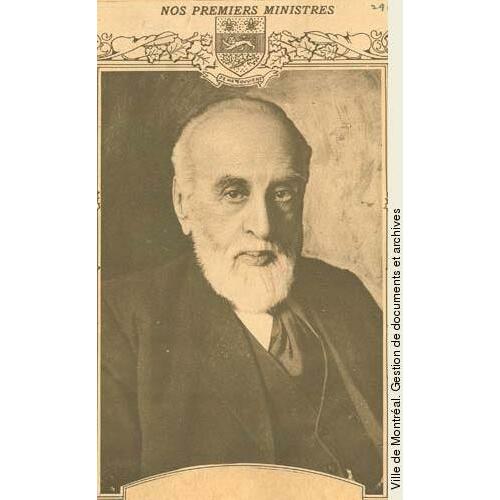

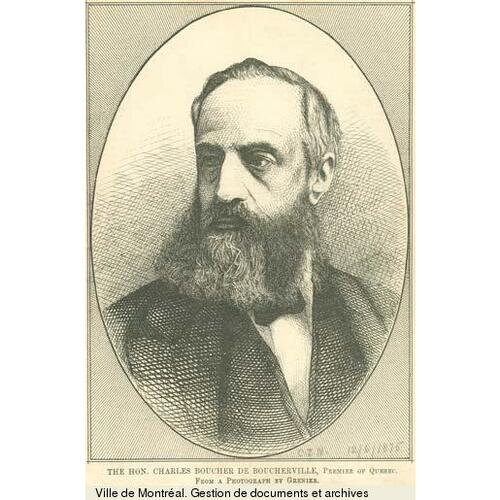

BOUCHER DE BOUCHERVILLE, Sir CHARLES (baptized Charles-Eugêne-Napoléon, he signed C. B. de Boucherville), physician and politician; b. 4 May 1822 in Montreal, one of the three children of Pierre de Boucherville, seigneur of Boucherville, and Marguerite-Émilie Bleury; younger brother of Georges de Boucherville*; m. first 4 Sept. 1861 Susan Elizabeth Morrogh in Montreal, and they had a child, but both mother and child died shortly after the birth; m. secondly 26 Sept. 1866 Marie-Céleste-Esther Lussier in Varennes, Lower Canada, and they had a son and a daughter; d. 10 Sept. 1915 in Montreal.

After completing his classical education at the Petit Séminaire de Montréal in 1840 with excellent marks, Charles Boucher de Boucherville enrolled in medicine at McGill College, from which he graduated with an md in 1843. Then, like many of the wealthy medical students of his generation, he went to study at the Université de Paris; he returned home that same year. After obtaining his licence from the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Lower Canada on 11 November, he established his practice in Varennes. He would remain there until 1861, when he abandoned medicine for politics and moved to Boucherville. As befitted a man of seigneurial ancestry, he became involved in all spheres of communal activity. He promoted and supported works of piety, education, and charity with his counsel and money; he served as captain of the 1st Battalion of Chambly militia; and he was inexorably drawn into politics.

Boucherville was first elected to the Legislative Assembly of the Province of Canada for Chambly on 4 July 1861. The following May he joined with many supporters of the government of George-Étienne Cartier* and John A. Macdonald* to vote against the Militia Bill, their defection causing the collapse of that administration. The new ministry formed by John Sandfield Macdonald* and Louis-Victor Sicotte* was soon found wanting; independents and Conservatives such as Boucherville defeated it in May 1863. In the elections which followed in June, Boucherville was re-elected for Chambly, and he remained its member until 1 July 1867. During this period he supported the “Great Coalition” [see George Brown*] which promoted confederation.

Following confederation, the new premier of Quebec, Pierre-Joseph-Olivier Chauveau*, appointed Boucherville speaker of the Legislative Council, thus automatically making him a member of the cabinet. He was sworn in on 15 July. The position of speaker was a recognition of his influence in the ridings south of Montreal where he, Gédéon Ouimet*, and Louis Archambeault* became the electoral strategists for the government. His appointment to the council for the division of Montarville was confirmed on 27 November. He would sit until his death in 1915. Boucherville soon became involved in the heated discussions surrounding the plans of the Roman Catholic bishop of Montreal, Ignace Bourget*, to carve up the Sulpician-controlled parish of Notre-Dame. In cabinet he unsuccessfully promoted the bishop’s plea for civil recognition of the new parishes he had created under canon law.

In February 1873 the new premier, Ouimet, replaced Boucherville as speaker with John Jones Ross*. Before long, however, the Ouimet government began to disintegrate because of the Tanneries scandal [see Louis Archambeault]. Conservatives looked to the upright Boucherville to form a new administration. Boucherville was seen as a suitable choice to undertake the political cleansing required. Although lacking political panache and charisma, he came from a family with a history of public service dating back to its ancestor Pierre Boucher*. He was not disliked by any faction of the Conservative party, being supported by the Roman Catholic clergy, respected by the English-speaking community, and able to rally the ultramontanes [see François-Xavier-Anselme Trudel*]. Nevertheless, the task of forming a cabinet acceptable to all was not easy and he had to rely on the intervention of Hector-Louis Langevin*, the leader of the federal Quebec Conservatives. He bought peace with the English-speaking community by continuing Joseph Gibb Robertson* as provincial treasurer. He reconciled the Bleus under Auguste-Réal Angers, who became solicitor general, and he made room for the impatient young opportunists under Joseph-Adolphe Chapleau* by appointing Levi Ruggles Church* attorney general. Sworn into office on 22 Sept. 1874, Boucherville became premier, provincial secretary, registrar, and minister of public instruction.

The main thrust of the first session of the legislature, which began in December 1874, was to distance the Conservatives from the Tanneries scandal and, it was hoped, to clear the Ouimet administration of wrongdoing. A committee was set up to inquire into the affair. The Conservatives, who formed the majority of the committee, prevented the report from commenting on the innocence or guilt of any member of the Ouimet cabinet, but they joined with the Liberals in recommending that the exchange of land which had caused the scandal be annulled. Boucherville thus effectively defused the issue.

Boucherville also marked his first session by introducing major electoral reforms, including the secret ballot, the holding of elections on the same day in all ridings, new property qualifications for voting, and new rules of eligibility for running. A number of corrupt practices to secure votes, such as gifts, loans, threats, and the distribution of food and drink, were outlawed. The reforms came into effect in time for the provincial general elections of 7 July 1875.

Returned to power with a solid mandate, Boucherville immediately tackled delicate issues of importance to the Roman Catholic Church. Besides giving civil recognition to Bourget’s parishes in Montreal, the government withdrew from what was possibly its most important area of intervention, the field of education. The key to this reform was the removal of politicians from interference with the educational system through the abolition of the Ministry of Public Instruction and the re-establishment of a department. The cabinet minister accountable to the assembly was replaced by a senior civil servant known as the superintendent of public instruction [see Gédéon Ouimet], who was to follow the directives of the Council of Public Instruction. In effect, politicians were ceding control of education to the Roman Catholic bishops and the Protestant leaders who dominated their respective committees of this council. The reform marked the end of the evolution of a single educational organization in Quebec and divided the system into two completely independent sections, based on religious persuasion. Boucherville would serve for a brief period as a member of the Catholic committee, resigning in 1888.

Besides radically altering the educational system, Boucherville changed railway policy. In September 1875 the government decided to take over construction of the North Shore Railway, from Quebec City to Montreal, and the Montreal Northern Colonization Railway, from Montreal to Ottawa. Merging the two lines, it created the Quebec, Montreal, Ottawa and Occidental Railway that year. Consequently, when the Grand Trunk Railway, which serviced the south shore of the St Lawrence, persuaded financiers not to grant the project needed capital, Boucherville was forced to intervene to protect the province’s substantial investment. Because of the severe depression in the 1870s, the government decided to stop subsidizing all railways except the Quebec, Montreal, Ottawa and Occidental.

In January 1876 Robertson, from the Eastern Townships, resigned because he was unable to obtain subsidies for a railway in his area. Taking this opportunity to remake his cabinet, Boucherville added agriculture and public works, including the railway, to his responsibilities. The new cabinet was sworn in on 25 Jan. 1876.

Burdened with a huge deficit, by 1878 the government found itself unable to continue the railway. Having borrowed more than $7,000,000 and exhausted further possibilities of credit, it decided to fall back on the municipalities along the rail route, since they had pledged funds but had yet to make any contributions. Boucherville introduced a bill at the end of January 1878 to force them to honour their commitments. This initiative provided the lieutenant governor, Luc Letellier* de Saint-Just, with an excuse to dismiss the premier.

Letellier, a Liberal, and Boucherville, a Conservative, had mistrusted one another from the outset of the lieutenant governor’s term, in December 1876. Because he believed Letellier would inform the Liberals of the government’s policy, Boucherville had held back information. He had also come to consider Letellier’s assent a simple matter of form. Some of his negligence resulted from having dealt in the past with an ailing lieutenant governor, René-Édouard Caron*. Nevertheless, Boucherville was wrong to issue, in November 1877, proclamations under Letellier’s signature which the lieutenant governor had never signed. On the other hand, Letellier had an inflated view of his role. He justly claimed that he should be consulted on all matters of administration and policy, but mistakenly believed that his wishes were binding on his ministers. His dismissal of Boucherville on 2 March 1878 was therefore questionable, the more so because Boucherville commanded a majority in the assembly.

Boucherville’s removal from office undermined his position as leader of the Conservatives. Letellier called on a Liberal without a majority, Henri-Gustave Joly*, to form a government and he granted him a dissolution. In the election of 1 May 1878 the Liberals gained a number of seats and held on to office. Because Angers, the house leader, had been defeated, the Conservatives turned to Chapleau to lead them in the assembly. Bowing to the inevitable, Boucherville resigned as leader of the party.

The contribution Boucherville had made to the Conservative party was not forgotten; when Sir John A. Macdonald returned as prime minister in the fall of 1878, he had the former premier appointed to the Senate. Boucherville took his seat for the division of Montarville on 13 Feb. 1879. Unlike some senators from Quebec, he focused largely on his province. He began to express opposition to the policies of the new Conservative government there led by Chapleau, who came to power in October 1879. Although smarting over Chapleau’s snatching of the party leadership, Boucherville did not break with him until the Quebec premier announced his railway policy in 1882.

Boucherville saw corruption at the heart of Chapleau’s division and sale of the Quebec, Montreal, Ottawa and Occidental [see Louis-Adélard Senécal*]. Chapleau viewed the line as part of a great transcontinental railway. Unable to persuade the Canadian Pacific Railway to take all of it over, he had settled for a compromise which would ensure the eastern summer terminus for Montreal. Boucherville saw the railway as a local line only, whose principal objective was to serve the population on the north shore of the St Lawrence. Because of accusations of criminal activity which surfaced after the deal, he called for an inquiry. Chapleau’s supporters attacked him mercilessly in the press; Joly, the leader of the opposition, invited him to join an alliance, but Boucherville was too much a Conservative to consider the offer, believing his party would survive the actions of some of its members. He received only partial satisfaction: the provincial government established a royal commission at the end of 1884 [see Sir Adolphe-Basile Routhier], but the sale of the railway was not revoked.

Although Boucherville had been unable while premier to solve the problem of the Jesuit estates [see Antoine-Nicolas Braun*], early in 1885 he prepared a plan which seems to have provided the basis on which the question was finally settled by the Liberal government of Honoré Mercier* in 1888. Boucherville, who was decidedly pro-Jesuit, accepted responsibility for steering the necessary bill through the Legislative Council.

Boucherville’s emphasis on provincial affairs had not kept him from further straining his relationship with Chapleau, a federal cabinet minister since July 1882. Chapleau, who actively defended the Conservative cabinet’s decision to hang Métis leader Louis Riel* in 1885, was disappointed that Boucherville remained silent on the issue. Further alienating Chapleau, Boucherville spoke against a section of a bill introduced by the minister in 1885 restricting Chinese immigration. Consequently, the following year Chapleau vetoed Boucherville’s entry into the provincial cabinet of John Jones Ross and refused to allow him to be appointed speaker of the Senate in the spring of 1891. Macdonald hoped Boucherville would be able to rally Conservatives in preparation for the upcoming elections; Chapleau argued that only a loyal supporter should receive the job.

Although denied the speakership, Boucherville received a larger prize that December, the premiership of his province. Strangely, he came to power through a coup d’état which mirrored the one that had cost him the premiership in 1878. On 16 December Lieutenant Governor Angers dismissed Premier Mercier because of the scandal over the Baie des Chaleurs Railway and called on Boucherville to form a government. When Boucherville assumed office on 21 Dec. 1891 Liberals questioned, as Conservatives had done in 1878, whether the lieutenant governor had the right to dismiss a premier who commanded a majority in the assembly. A second constitutional question arose when Boucherville, hoping to obtain a Conservative majority, immediately advised the lieutenant governor to dissolve the legislature and call an election for 8 March 1892. The Liberals argued that a new session was required by 29 Dec. 1891 because, under the constitution, a parliament had to be held every 12 months. Boucherville replied that the people would decide if his actions were justified; he received an overwhelming majority.

During his second administration Boucherville maintained peace with the Roman Catholic Church by avoiding a number of thorny issues, such as the Manitoba school question [see Thomas Greenway*], additional reform of the educational system, and state intrusion into asylums. He continued colonization work in the Lac Saint-Jean area and allowed women to vote in municipal and school elections, although they could not run for office. Nevertheless, his primary focus was on finances. Under Mercier the provincial debt had more than doubled and ordinary expenditure had increased by almost one-third. The premier’s solution was a series of taxation bills: one imposed a tax on every shopkeeper and every firm engaged in manufacturing; a second taxed members of the liberal professions, such as lawyers and engineers; a third increased taxes on commercial corporations; others placed duties on transfers of real estate and introduced succession duties. Accepted by major business interests, these harsh measures were not universally popular.

Boucherville was not destined to have to live with the consequences. At the end of 1892 Chapleau and Angers exchanged positions; Boucherville immediately informed the new Canadian prime minister, Sir John Sparrow David Thompson*, that he would refuse to serve under Chapleau as lieutenant governor. After submitting his resignation, he advised Chapleau to call on Louis-Olivier Taillon* to form a new government. He left office on 16 Dec. 1892. Although Chapleau suggested that Boucherville’s decision had too much pride and too little duty in it, they parted on good terms. For his services, on 26 May 1894 he was made a cmg.

Into his seventies and entering the twilight of his career, Boucherville continued to comment on the issues of the day from his seats in the Legislative Council and Senate. He strongly supported Prime Minister Sir Charles Tupper, who promised remedial legislation to settle the Manitoba school question in 1896, and he opposed the attempts of Quebec Premier Félix-Gabriel Marchand* to abolish the Legislative Council in 1900.

Federal matters took precedence in the latter part of his life. When, in July 1899, the House of Commons passed a carefully worded resolution supporting certain British actions against the Boers, he spoke in the Senate against condemning the Boers without official knowledge of the situation. He strongly advocated the creation of a national capital district in the Ottawa region, similar to the District of Columbia in the United States. In contrast to his orthodox approach to economic questions, Boucherville was more liberal than most Canadians on the matter of Chinese immigration. He opposed the government’s increase in the Chinese head tax from $100 to $500 in 1903 because he did not believe British subjects (some Chinese came from Hong Kong) should be forced to pay $500 to come to Canada and because the new legislation amounted to the prohibition of Chinese immigration.

Boucherville’s last great political fight concerned the establishment of a Canadian navy. At age 87 he spoke against the Naval Service Bill proposed by the Liberal government of Sir Wilfrid Laurier because the creation of a navy involved an enormous expense and because the fleet, if placed under British command, might draw Canada into conflicts without its consent. Like a number of Quebec Conservatives, he opposed his own party’s policy on the issue and urged that a referendum be held. He found himself on the losing side of this issue, as he did at age 91 in 1913 when he supported the Conservatives’ Naval Aid Bill, defeated in a Liberal-dominated Senate. For his loyal service, Prime Minister Robert Laird Borden* secured a knighthood for him on 22 June 1914.

Hale and alert to the end, Boucherville took ill in early September 1915 and died a week later. A capable and experienced parliamentarian, he was always a gentleman. He was fluent in both English and French, clever in repartee, a great conversationalist although a poor speaker, and an omnivorous reader with a retentive memory. Handsome and distinguished, he had travelled much of the world and enjoyed recounting the legends and stories of French Canada to anyone who would listen.

A lover of history, Boucherville has received scant attention from historians. No one has written his biography and he is mentioned only in passing in general works. He was, however, a far more important figure in French Canadian public life than this historiography would seem to indicate. Close to the centre of power for five and a half decades, he represented a disappearing class of individuals who viewed public office as a trust to be accepted out of duty to the community. He found himself at odds with a new breed of professional politician who sought power in order to divide the spoils of office. Staunchly Roman Catholic, he believed religion had a role to play in the community, in contrast to those who favoured separation of church and state. Generally influencing policy from behind the scenes, he worked tirelessly to maintain the dominance of the Conservative party.

ANQ-M, CE1-51, 6 mai 1822, 4 sept. 1861; CE6-10, 26 sept. 1866. NA, MG 26, A; D. Montreal Daily Star, 11 Sept. 1915. L.-P. Audet et Armand Gauthier, Le système scolaire du Québec (2e éd., Montréal, 1969). [Georges de Boucherville], The DeBoucherville government and the causes which led to their dismissal; an historical account (Montreal, 1878). Can., Parl., Sessional papers, 1879, no.19; Senate, Debates, 1879–1916. Canadian directory of parl. (Johnson). Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898 and 1912). J. Desjardins, Guide parl. M. Hamelin, Premières années du parlementarisme québécois. [Louis Lalande], Une vieille seigneurie, Boucherville; chroniques, portraits et souvenirs (Montréal, 1890). K. J. Munro, The political career of Sir Adolphe Chapleau, premier of Quebec, 1879–1882 (Queenston, Ont., [1992]). Qué., Assemblée Législative, Débats, 1871–75; Journaux, 1874–75; Commission royale, Enquête concernant le chemin de fer Québec, Montréal, Ottawa et Occidental (4v., Québec, 1887); Conseil Législatif, Débats, 1882. Rumilly, Hist. de la prov. de Québec, vols.1–12.

Revisions based on:

McGill College, Calendar (Montreal), 1859–60.

Cite This Article

Kenneth Munro, “BOUCHER DE BOUCHERVILLE, Sir CHARLES (baptized Charles-Eugêne-Napoléon; C. B. de Boucherville),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 30, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/boucher_de_boucherville_charles_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/boucher_de_boucherville_charles_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | Kenneth Munro |

| Title of Article: | BOUCHER DE BOUCHERVILLE, Sir CHARLES (baptized Charles-Eugêne-Napoléon; C. B. de Boucherville) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1998 |

| Year of revision: | 2018 |

| Access Date: | March 30, 2025 |