As part of the funding agreement between the Dictionary of Canadian Biography and the Canadian Museum of History, we invite readers to take part in a short survey.

PīTIKWAHANAPIWīYIN (Poundmaker), Plains Cree chief; b. c. 1842 in what is now central Saskatchewan, the son of a Stoney (Nakoda) father, Sīkākwayān (Skunk Skin), and a mixed-blood mother; d. 4 July 1886 at Blackfoot Crossing (Alta).

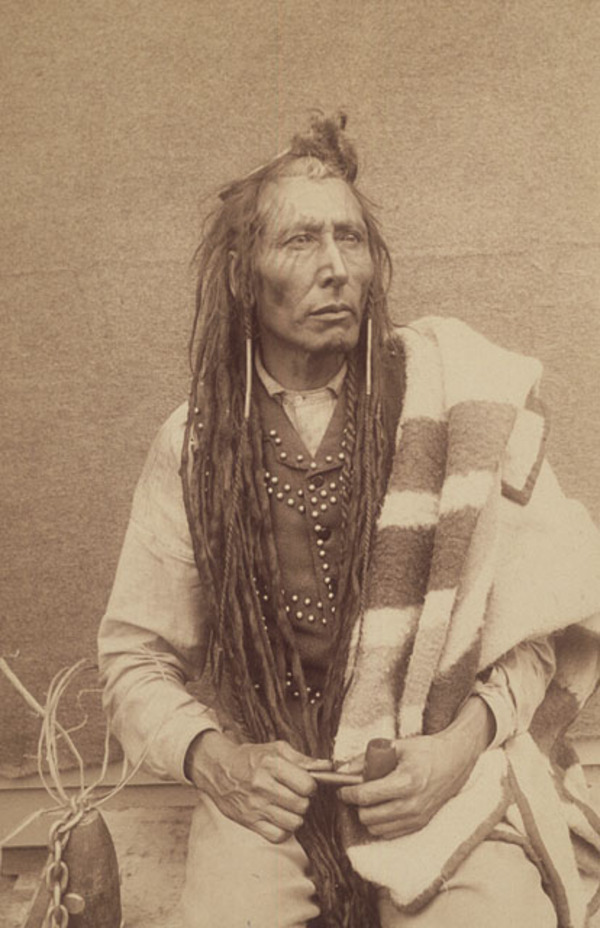

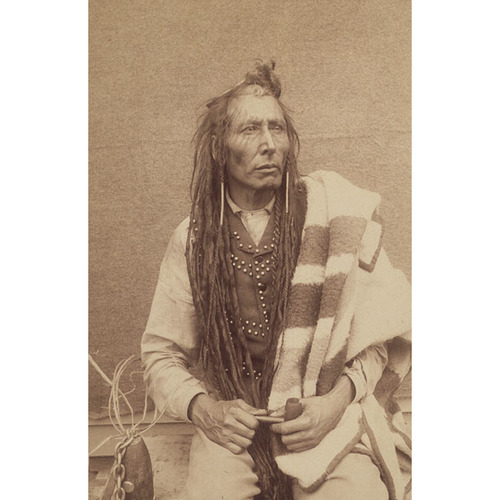

Poundmaker was born into a prominent Plains Cree family from the House band, his maternal uncle being Mistawāsis (Big Child), a leading chief in the Eagle Hill (Alta) area. Although his mother was a descendant of a French Canadian, Poundmaker was entirely Plains Cree in culture and appearance. Robert Jefferson, the farm instructor on the Poundmaker Reserve, writing some years after Poundmaker’s death, described him as “tall and good looking, slightly built and with an intelligent face, in which a large Roman nose was prominent; his bearing was so eminently dignified and his speech so well adapted to the occasion, as to impress every hearer with his earnestness and his views.”

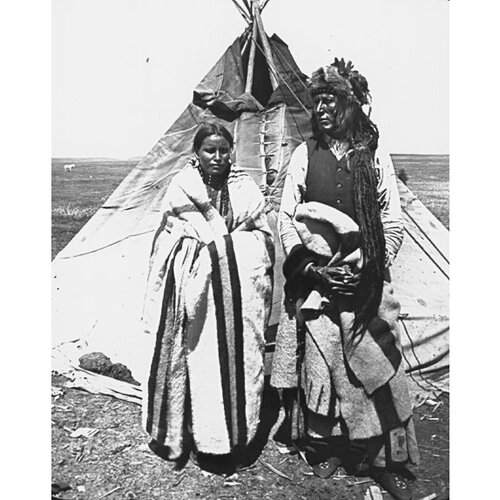

A trader who encountered Poundmaker in the late 1860s recalled that at that time “he was just an ordinary Indian, [an] ordinary man as other Indians.” Poundmaker’s life changed, however, after Crowfoot [Isapo-muxika], a head chief of the Blackfoot, lost a son in 1873 during a raid on a Cree camp. Not long after, when a short-lived peace treaty was made between the two nations, one of Crowfoot’s wives saw Poundmaker and was struck by his resemblance to her dead son. The Blackfoot chief immediately adopted the Cree and invited him to remain with the Blackfeet at Blackfoot Crossing, giving Poundmaker a Blackfoot name, Makoyi-koh-kin (Wolf Thin Legs).

When Poundmaker returned to the Crees, his influence with the Blackfeet as Crowfoot’s son and the wealth in horses gained from his new family gave him increased status among his own people. By August 1876, when the indigenous communities of central Saskatchewan came together at Fort Carlton to negotiate a treaty with the Canadian government, he was considered to be a councillor, or minor chief, under Pihew-kamihkosit (Red Pheasant) of the River people. Unlike his uncle, Mistawāsis, Poundmaker questioned the intent of Treaty No.6 after the lieutenant governor of Manitoba and governor of the North-West Territories, Alexander Morris, outlined the terms. Poundmaker claimed that the government should be prepared to provide indigenous communities, including future generations, with instruction in farming and assistance after the buffalo had gone, in exchange for their lands. When the lieutenant governor demurred, Poundmaker said that he had no knowledge of building houses or farming, and added: “From what I can hear and see now, I cannot understand that I shall be able to clothe my children and feed them as long as the sun shines and water runs.” In the end, however, Poundmaker accepted the terms of the treaty and signed on 23 Aug. 1876. Two years later, when Pihew-kamihkosit agreed to settle on a reserve, Poundmaker formed his own band, which continued to hunt the diminishing herds of buffalo, but in 1879 he too accepted a reserve and settled at the confluence of Battle River and Cut Knife Creek, about 40 miles west of Battleford (Sask.); he continued to hunt whenever the opportunity arose.

In 1881 Poundmaker was chosen to accompany the Marquess of Lorne [Campbell*], governor general of Canada, on a tour from Battleford to Blackfoot Crossing. During this trip Poundmaker impressed the viceregal party with his knowledge of Cree culture and his philosophy as a peacemaker. Poundmaker, too, was impressed with the information gained from the dignitaries, and several months later, when providing a feast for his band, he urged his followers to remain peaceful; “. . . the whites will fill the country,” he said, “and they will dictate to us as they please. It is useless to dream that we can frighten them, that time has passed. Our only resource is our work, our industry, our farms.”

In 1883, as part of a government economy drive, many Indian Department employees were dismissed and rations to indigenous populations reduced. Delays in delivering supplies caused rumours to spread that rations would be curtailed completely and communities left to starve. Moreover, as complaints by the agents that people were starving after the severe winter of 1883–84 went unheeded by officials in Ottawa, Poundmaker was unable to maintain peace among his followers, particularly the younger warriors. In June 1884, many indigenous people, including Big Bear [Mistahimaskwa] and his followers, assembled at Poundmaker’s reserve to discuss the situation. In spite of the efforts of the North-West Mounted Police to disperse them, more than 1,000 Crees put on a Thirst Dance, their major religious celebration, in which the participants reaffirmed their faith in the sun spirit. During the ceremonies a man was accused of assaulting John Craig, the farm instructor on an adjacent reserve. Anticipating a possible outbreak of violence, the NWMP fortified the Battleford agency and sent a force of some 90 men to arrest the accused. However, Poundmaker and Big Bear refused to turn him over while the Thirst Dance was in progress, and Poundmaker offered himself as a hostage. Later, when the police threatened to arrest the wanted man forcibly, Poundmaker denounced their actions, angrily waving a four-bladed war club at them. But the fugitive was taken into custody and escorted to Battleford, where he was sentenced to a week in jail.

The kind of discontent reflected in this altercation was rampant throughout much of the prairies, among Métis and First Nations. It resulted in Métis spokesmen inviting Louis Riel to return from Montana to seek a solution. Poundmaker played no part in sending for Riel; however, because of his leadership, especially of the young warrior element, at the outbreak of the rebellion in 1885 his camp grew in population to several times its normal size and included Cree, Stoney, and even a number of Métis. After the Métis victory at Duck Lake in March and the killing of a farm instructor by Stoney men, most of the white settlers abandoned their farms and fled to the barracks of the NWMP near Battleford, while a few others who had been taken prisoner by Poundmaker’s followers found shelter in his lodge. The chief then travelled to the Battleford barracks, located about a quarter of a mile from the village, to see the Indian agent and to obtain overdue rations. When the agent refused to leave the protection of the NWMP, Poundmaker was unable to prevent the young warriors accompanying him from ransacking the village, which had also been abandoned for the barracks by its inhabitants.

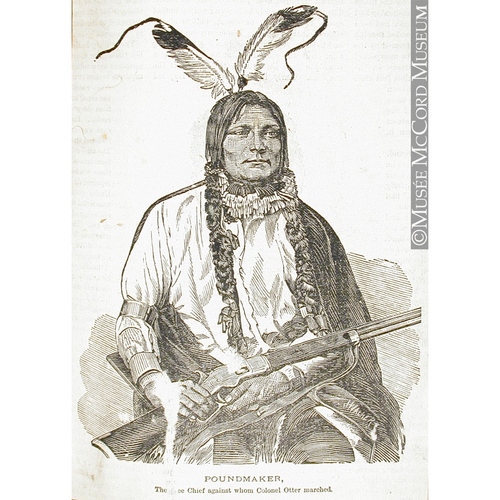

After the group returned to Cut Knife Creek, Poundmaker remained their nominal leader with considerable influence, but a warrior’s lodge erected in the camp became the real centre of authority. In particular, a number of Stonies who had been involved with the killing of the farm instructor actively supported a policy of open warfare against the whites. In the mean time, Lieutenant-Colonel William Dillon Otter*’s column arrived at Battleford. Deciding to “punish” Poundmaker for pillaging the village, Otter set off with 325 men, two cannons, and a Gatling gun to attack Poundmaker’s camp near Cut Knife Hill. However, in the early morning of 2 May 1885 news of the advancing column was received, and a number of Cree and Stoney warriors immediately set out to thwart the government attack. After seven hours of fighting, Otter’s forces withdrew. Although Poundmaker had played no part in the battle, he was able to prevent the warriors from pursuing the retreating forces. Otter’s army was in sufficient disarray by this time that any further conflict would have resulted in heavy losses.

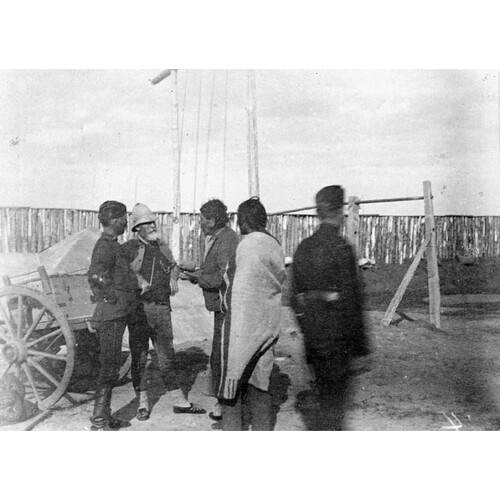

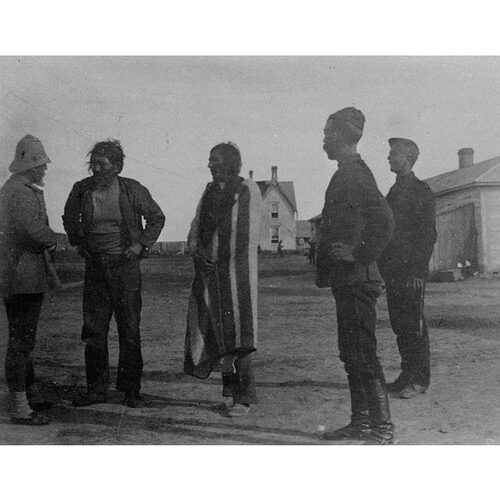

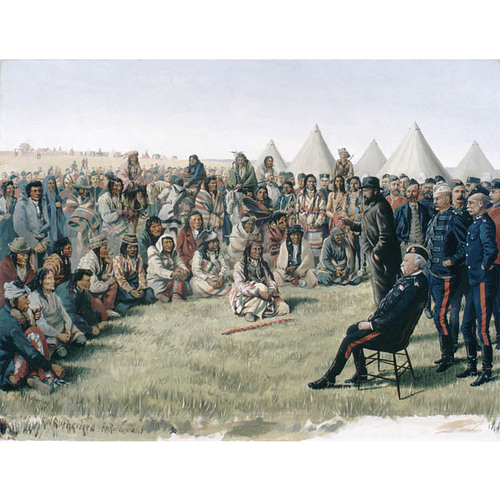

After the attack a number of Métis persuaded Poundmaker’s camp to join Riel’s forces at Batoche. Poundmaker himself made several attempts to travel instead to Devil’s Lake, but the Stoney warriors would not permit it. A short time later, when the Métis captured a wagon supply train, through the intervention of Poundmaker the prisoners were protected and well treated. When the camp learned that Riel’s forces had been defeated at Batoche on 12 May, Poundmaker sent a priest, Father Louis Cochin, with a message to Major-General Frederick Dobson Middleton*, saying he was prepared to negotiate a peace settlement. The general rebuffed the appeal and demanded that Poundmaker surrender unconditionally at Battleford. On 26 May Poundmaker and his followers came into the fort, where they were immediately imprisoned.

Poundmaker was put on trial for treason at Regina in July 1885. “Everything I could do was done to stop bloodshed,” Poundmaker protested in court. “Had I wanted war, I would not be here now. I should be on the prairie. You did not catch me. I gave myself up. You have got me because I wanted justice.” He was found guilty and sentenced to three years in prison. After serving a year in Stony Mountain Penitentiary, Man., broken in spirit and health, he was released. Only four months later, while visiting his adoptive father, Crowfoot, on the Blackfoot reserve, he suffered a lung haemorrhage and died.

Not until the rebellion hysteria had passed was Poundmaker belatedly recognized as a man who had never abandoned the peacemaker’s role and had fought only in defensive actions. Official acknowledgement of these facts came much later. On 23 May 2019 at the Poundmaker Cree Nation, northwest of Saskatoon, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, on behalf of the Government of Canada, “fully exonerated” Poundmaker “of any crime or wrongdoing.” In “an apology for the historic injustices, hardships and oppression suffered by Chief Poundmaker and your community,” he noted, “It has taken us 134 years to reach today’s milestone.”

Can., Parl., Sessional papers, 1886, XIII, no.52. Louis Cochin, Reminiscences . . . a veteran missionary of the Cree Indians and a prisoner in Poundmaker’s camp in 1885 . . . ([Battleford, Sask., 1927]). Robert Jefferson, Fifty years on the Saskatchewan . . . (Battleford, 1929). Morris, Treaties of Canada with the Indians. W. H. Williams, Manitoba and the north-west: journal of a trip from Toronto to the Rocky Mountains . . . (Toronto, 1882), 104–10. John Maclean, Canadian savage folk: the native tribes of Canada (Toronto, 1896). Norma Sluman, Poundmaker (Toronto, 1967). Stanley, Birth of western Canada; Louis Riel. Mary Weekes, Great chiefs and mighty hunters of the western plains . . . (Regina, [1947?]), 7–27. [Edward Ahenakew], “The story of the Ahenakews,” ed. R. M. Buck, Saskatchewan Hist. (Saskatoon), 17 (1964): 12–23. J. W. Shera, “Poundmaker’s capture of the wagon train in the Eagle Hills, 1885,” Alberta Hist. Rev. (Edmonton), 1 (1953), no.1: 16–20.

Revisions based on:

Justin Trudeau, Prime Minister of Can., “Statement of exoneration for Chief Poundmaker”: pm.gc.ca/eng/news/2019/05/23/statement-exoneration-chief-poundmaker (consulted 10 June 2019).

Cite This Article

Hugh A. Dempsey, “PĪTIKWAHANAPIWĪYIN (Poundmaker),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 29, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/pitikwahanapiwiyin_11E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/pitikwahanapiwiyin_11E.html |

| Author of Article: | Hugh A. Dempsey |

| Title of Article: | PĪTIKWAHANAPIWĪYIN (Poundmaker) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1982 |

| Year of revision: | 2019 |

| Access Date: | March 29, 2025 |