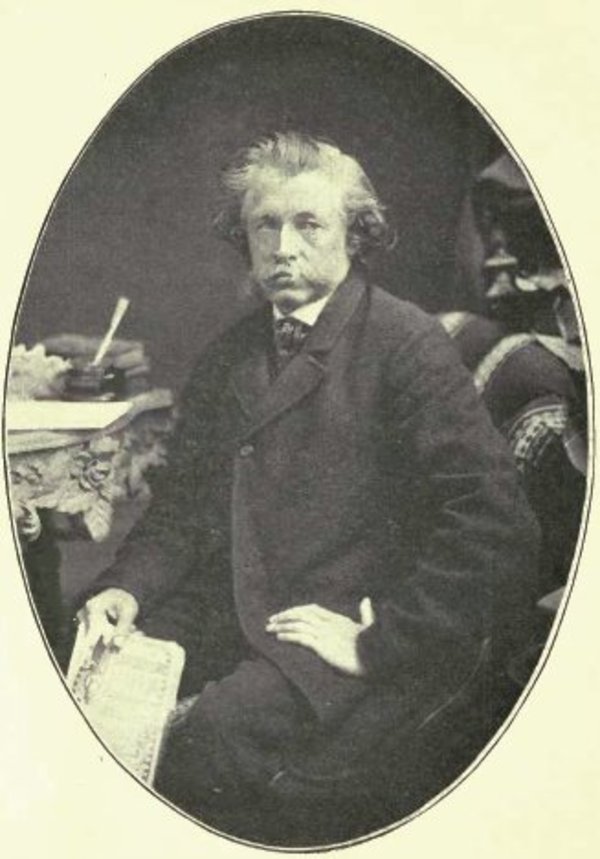

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

SANGSTER, CHARLES, poet, civil servant, and journalist; b. 16 July 1822 near Kingston, Upper Canada, son of James Sangster and Ann Ross; m. first 16 Sept. 1856 Mary Kilborn (d. 1858) in Kingston; m. secondly 30 Oct. 1860 Henrietta Charlotte Meagher at Niagara Falls, and they had three daughters and one son; d. 9 Dec. 1893 in Kingston.

By temperament quiet and introspective, Charles Sangster strove for harmony in his relationship with humanity and for spiritual fulfilment in God’s will. His life, however, was characterized by an unfortunate series of events that, after the mid 1860s, contributed to anxiety, to uneven literary productivity, and eventually to nervous breakdown. An understanding of these paradoxes and how they shaped his work elicits respect for the artist, whose life was committed to poetry. His talent dominates the literature of colonial Canada, and his creations earned the accolades of readers and reviewers of his time.

Sangster’s life was defined within a narrow geographic area from Kingston to Ottawa; visits to relatives and friends widened the circumference to include Montreal, Niagara Falls, and Buffalo, N.Y. Paradoxically, his imagination carried him throughout the world. Though outwardly kind and passive, he expressed in his poetry deep feeling and personal conflict. He described himself in a note to his friend and literary executor William Douw Lighthall* as “a self made and pretty much a self taught man,” yet his work reveals extensive knowledge of geography, history, literature, science, and contemporary events.

The poet’s paternal grandfather came from Leith, Scotland. According to Sangster’s description, “a fiery old Scot . . . brave as a lion,” he fought in the American revolution and later settled in Prince Edward Island. There he married an “Irish woman,” and they had seven sons, including Charles’s father, James. James grew up on the Island, where he married Ann Ross, daughter of Hugh Ross, also from Scotland. “So I suppose,” Sangster later wrote, “the Scotch will, with some justice, lay claim to me, although my grandmother on my father’s side was Irish, and my grandmother on my mother’s side was English almost.”

Sangster’s parents left Prince Edward Island, possibly in 1802 or 1803, and proceeded “upward to Canada.” They may have lived at Quebec for a few years but by 1814 were settled in Kingston, where James received a grant of land as a result of his military attachment. He was employed with the navy yard at Point Frederick as a “joiner,” “shipwright,” or “shipbuilder,” and his responsibilities required him to move from port to port on the Great Lakes. He died before Charles was two years old, leaving Ann to raise the five surviving children alone. She, as Charles reports, “honorably brought up and provided for [them] by the labour of her hands.”

Charles had no family members or known acquaintances of literary culture who might have influenced his artistic development. His education was meagre, not only because of the absence of good teachers but also through his own lack of interest. In his words, he “went to school for a number of years, and learned to read and write if nothing more.” Yet he has also recalled that in his younger days he would have read more if he had had the opportunity; few books were available, and he believed that “thinking [my] way without them may have done [me] good.” “The Bible, the Citizen of the World, by dear old Noll, in two volumes, made up all [my] library for many years, with an occasional Sunday School prize . . . until cheap literature came. . . . There was no Sanford and Merton, no Arabian Nights, or Robinson Crusoe until [I] had almost attained maturity.” At the age of 15 he had to leave school to help support his family.

Nevertheless, two years later Sangster had nearly completed a long narrative poem in iambic tetrameter couplets titled “The rebel,” which he never published. He would later send it to Lighthall explaining that it had been “intended for a poem in Three Cantos, but [was] found among my papers absolutely forgotten, where it had lain since 1839.” The poem, 757 lines in length, contains an extensive vocabulary and rich and imaginative historical and geographical allusions, which reveal a maturity of mind beyond what might be expected of a boy, even a superior one, who had so little formal education. It is his earliest known work, but the content and form suggest considerable previous writing.

Like his formal education, Sangster’s first jobs were modest. On leaving school in 1837, he took full-time employment in the laboratory at Fort Henry, making cartridges for the defence of the fort during the rebellion. Two years later he was transferred to the Ordnance office at the fort, where in his own words he “ranked as a messenger, received the pay of a labourer, and did the duty of a clerk.” He continued in this work for ten years until, frustrated and disgusted, he left Kingston and moved to Amherstburg. There he became editor of the weekly Courier and Western District Advertiser. Little else is known about Sangster during the period 1837–49, but he evidently continued to develop his literary aptitude. He published poems, usually anonymous or pseudonymous, in newspapers. Many of the pieces that would later appear in The St. Lawrence and the Saguenay were written or drafted during this period.

Following the death of James Augustus Reeves, owner of the Courier, in the autumn of 1849, Sangster returned to Kingston to take a job as a proof-reader and bookkeeper with the British Whig [see Edward John Barker*] the following spring. He continued in this position at least until 1861, perhaps to 1864. These years of busy and possibly monotonous work with the paper were productive poetically. They culminated in The St. Lawrence and the Saguenay, and other poems, published in 1856 at Sangster’s expense by John Creighton* and John Duff in Kingston and Miller, Orton and Mulligan of Auburn, N.Y.

The book was received with unanimous acclaim as the best and most important book of poetry produced in Canada until that time. Readers and reviewers in North America and Britain praised the work and the man. Susanna Moodie [Strickland*] wrote a warm congratulatory letter from Belleville on 28 July: “Accept my sincere thanks for the volume of beautiful Poems with which you have favored me. If the world receives them with as much pleasure as they have been read by me, your name will rank high among the gifted Sons of Song. If a native of Canada, she may well be proud of her Bard, who has sung in such lofty strains the natural beauties of his native land.” A London magazine commented, “Well may the Canadians be proud of such contributions to their infant literature. . . . There is much of the spirit of Wordsworth in this writer, only the tone is religious instead of being philosophical. . . . In some sort, and according to his degree, he may be regarded as the Wordsworth of Canada.”

The volume reveals a wide knowledge of the classics, history, mythology, and British and American authors, including Shakespeare, Milton, Burns, Shelley, Scott, Byron, Wordsworth, Tennyson, P. J. Bailey, Longfellow, and Whittier. It contains threads of melancholy and despondency interwoven with joy in animate and inanimate nature and with religious optimism. Sangster’s most successful themes are love (the dominant one), nature, and religion; less successful are the frequently sentimental reflections on children, acquaintances, and domestic matters. The nature poems are the most descriptively accurate and aesthetically accomplished by any British North American poet to his time.

The title poem is Sangster’s most ambitious composition. In 110 Spenserian stanzas, interspersed with a number of lyrical pieces, it describes a voyage down the St Lawrence River from Kingston and up the Saguenay. The poet is stirred by the majestic scenery and the rich history and legend it evokes. The poem is also a journey away from civilization into nature and toward God as revealed in nature. The narrator and the mysterious “Maiden” who is his guide travel down the St Lawrence, symbolic of the material world, and up the Saguenay, which represents the spiritual life, to ultimate union with each other and with God. These themes are summed up in the concluding stanza:

All, all is thine, love, now: Each thought and hope

In the long future must be shared with thee.

Lean on my bosom; let my strong heart open

Its founts of love, that the wild ecstacy

That quickens every pulse, and makes me free

As a God’s wishes, may serenely move

Thy inmost being with the mystery

Of the new life that has just dawned, and prove

How unutterably deep and strong is Human Love.

Sangster’s ability to express the beauty of the Canadian landscape and the themes of love and spiritual life in a style never used before in his own country earned him the title, from some contemporary reviewers, of the father of Canadian poetry.

In September 1856 Sangster married 21-year-old Mary Kilborn, and the preponderance of love poetry in his first volume no doubt reflects his personal experience. Their happy union ended suddenly 16 months later on 18 Jan. 1858, when Mary died of pneumonia. Memories of the marriage would live in his consciousness for the rest of his life.

In 1860 Sangster’s second volume, Hesperus, and other poems and lyrics, appeared. It was published by John Lovell in Montreal and Creighton in Kingston. Although this collection of 75 poems contains the same general themes as the 1856 volume, it also reveals a tone of personal grief arising from Mary’s death. There is a new preoccupation with patriotic themes that reflects the growing nationalism in pre-confederation Canada, themes that will dominate Sangster’s later collection “Norland echoes.” The poems range in time from “The Plains of Abraham” and “Death of Wolfe” to a “Song for Canada,” whose “Sons are living men, / [Her] daughters fond and fair.” “Brock,” written for the inauguration of the new monument to Sir Isaac Brock* at Queenston Heights in 1859, demonstrates Sangster’s ability to create a successful occasional poem. After establishing the unity of Canadians in honouring the dead – “One voice, one people, one in heart / And soul, and feeling, and desire!” – he gives Brock a universal and timeless aura through the use of classical allusions:

Some souls are the Hesperides

Heaven sends to guard the golden age

………………………………

True Martyr, Hero, Poet, Sage:

And he was one of these.

………………………………

Wrestling with some Pythonic wrong,

In prayer, in thunder, thought, or song;

Briareus-limbed, they sweep along,

The Typhons of the time.

Sangster’s belief in pure Christian morality, his idealization of the past, and his joy in the simple, primitive life of the pioneer infuse his descriptions of nature, his patriotic poems, and the light songs and introspective lyrics that are his best work in the volume. Hesperus was well received, and many critics considered it superior to The St. Lawrence and the Saguenay, as did Sangster himself.

He became a reporter for the Kingston Daily News in 1864. The same year 13 selections from his two published volumes and three new poems appeared in Edward Hartley Dewart*’s Selections from Canadian poets . . . (Montreal), the first anthology of Canadian poetry. He wrote “The Bryant Festival” for the celebration held in New York on the occasion of American poet William Cullen Bryant’s 70th birthday. In this eventful year as well he and his second wife, Henrietta Charlotte, had a daughter, Charlotte Mary – his first child. By 1867, however, he was in a poor financial situation and suffered increasingly from ill health, depression, and a nervous disorder that would cause him deep mental pain the rest of his life. The exact nature and cause of the illness are unknown.

At the height of his popularity, and indeed when a third and fourth volume might have been expected to follow, Sangster was awarded an appointment at the Post Office Department in Ottawa on 20 March 1868. He was nominated by his neighbour, politician Alexander Campbell, who was postmaster general. Sangster’s salary as a senior second-class clerk was $500 a year. (It would rise to $1,300 by 1879 and to $1,400 two years later.) He remained with the Post Office for 18 years. The appointment required such heavy work that Sangster had no time to write poetry or to rewrite and edit poems completed before he left for Ottawa. He did not even have the opportunity to polish a manuscript he took with him, and he would return to Kingston in 1886 with it still untouched.

In 1868 his daughter, Charlotte Mary, died of diphtheria on 6 April, three weeks after the family had arrived in Ottawa. She was three years old. A second daughter, Florence, had been born at Kingston the same year. Gertrude would be born in Ottawa in 1870 and his only son, Roderick, in 1879.

The year 1868 saw the appearance of Sangster’s poem “The greater sphinx” in Stewart’s Literary Quarterly Magazine, published in Saint John, N.B., by George Stewart*. It was followed in 1869 in the same journal by another poem, “The oarsmen of St. John,” and an article on a new edition of Charles Heavysege*’s Saul: a drama, in three parts, published in Boston that year. Sixteen poems were published between 1870 and 1878 in Belford’s Monthly Magazine (Toronto), the Canadian Monthly and National Review (Toronto), and Stewart’s quarterly. Sangster’s low literary productivity during these years reflects his overwork and his poor health. Most of what he published at this time had been written before he moved to Ottawa. In 1875 he suffered a nervous breakdown. To reduce his work-load, he was appointed private secretary to the deputy postmaster general though he remained in the official category of senior second-class clerk.

The 1880s were a period of significant change and great sadness in Sangster’s life. His wife died some time between 1883 and 1886, leaving him to raise their three children. In March 1886, after another breakdown in his health, he took a six-month leave from his job. That year he resigned from the Royal Society of Canada, to which he had been elected a charter fellow in 1882; he had attended the first four meetings but had not presented any papers. Finally in September he retired from the civil service to live in Kingston. For the next two years he rested and did little but try to regain his health; he never fully recovered.

On 8 July 1888 Sangster received a letter from Lighthall enquiring about poems from The St. Lawrence and the Saguenay and Hesperus for a forthcoming anthology, most probably his Songs of the great dominion . . . , which was published in London the following year. The letter, showing interest in Sangster’s work, was answered the same day, and the correspondence between the two men that followed revitalized the poet. For the next five years, until his death in 1893, Sangster devoted his time and energy to revising and editing his 1856 and 1860 volumes and to completing two other collections, which, however, remained unpublished in his lifetime.

Except for moments of sadness caused by a lost love or the death of a friend, the tone of the 1856 and 1860 volumes as published is generally optimistic. The poems reflect the poet’s joy in love, friends, art, and nature, and his faith in God. By 4 July 1891, when at the age of 68 Sangster completed the two manuscript collections and mailed them to Lighthall, the focus of his poetry had changed significantly. In “Norland echoes and other strains and lyrics,” which contains 60 poems including the untitled introduction, patriotism has become the dominant theme. It is expressed with admirable openness and sincerity. The collection opens with “Our norland” and closes with the same pride of country in “Our own far-north”; the pair enclose poems on Canadian places, historical events, and people. “The angel guest and other poems and lyrics” contains 33 poems without formal or thematic division. The title piece and the final poem, “Flights of angels,” express the influence of angels on human life. The collection does not contain any new themes but confirms the thematic preoccupations of Sangster’s other three volumes, with their stylistic strengths and weaknesses. The poems in both these collections were probably written before he left for Ottawa in 1868, and they likely do not reflect Sangster’s mental state in the 1870s and 1880s.

Early in his correspondence with Lighthall, on 13 July 1888, Sangster wrote that Hesperus “is nearly alright.” He then made some two hundred revisions that improve the diction, imagery, rhythm, and action. These adjustments indicate no changes in his philosophy, but they reinforce the beliefs he held when he first published Hesperus in 1860, and they enhance the expression and smoothness of the poems.

Displeased with the quality of The St. Lawrence and the Saguenay, Sangster rewrote the title poem, beginning in the 1860s, extending it to approximately 220 stanzas; he deleted many of the miscellaneous poems in the volume, made more than 2,000 alterations to those that remained, and added several new ones. He sent the revised title poem to his cousin Amos W. Sangster, an artist in Buffalo, to be illustrated, and it was placed in Amos’s safe for security. When the artist died, all trace of this manuscript was lost.

Excerpts from the revised “St. Lawrence and the Saguenay” appeared in a number of books and magazines during Sangster’s lifetime. The 29 new and 11 revised stanzas that have thus survived add a new dimension to the poem, showing the direction he was giving it, as well as suggesting the quality of the extended work. The revisions indicate the poet’s development in refining his technical skill and the degree to which he was influenced by the ideas, themes, and techniques of the confederation poets, Charles George Douglas Roberts*, William Bliss Carman*, Archibald Lampman, and Duncan Campbell Scott*, who were active during the last ten years of Sangster’s life.

Of the 62 “miscellaneous poems” in Sangster’s revision of The St. Lawrence and the Saguenay, 20 are expressions of romantic love, and these are the best in the volume. The lyric predominates, followed in frequency by Spenserian verse songs, blank verse, and sonnets. Sangster’s facility with the lyric is distinctive in Canadian poetry of his time. His ability to compress his ideas within a tight form and his skill in modifying the refrain to suggest a progression in the theme parallel the concern with structure in poetry being written in France and England from the mid 19th century.

Sangster’s correspondence with Lighthall, consisting of twelve letters and four postcards, is the only source for our knowledge of Sangster’s final years. The letters contain a detailed account of his revisions to his poems and reveal his attitude to his writing and to his civil service appointment. They show how this job “destroyed,” to use his own words, his “literary chances.” Lighthall’s letters to Sangster are not extant. He became one of Sangster’s literary executors, and shortly after the poet’s death he deposited the letters, unpublished manuscripts, and all associated documents in the McGill University library, where they remain.

Charles Sangster is the best of the pre-confederation poets. The revisions he made in the last five years of his life show that by the late 1880s he had appreciably refined his skill but remained a man enclosed in the ethos of the colonial period. It is fortunate for the history of Canadian literature that Lighthall motivated him to complete his revision of his two published works and to prepare the two other collections for publication. Together with the letters, they reveal a man of commendable talent who, despite educational, cultural, and vocational barriers, made a major contribution to Canadian poetry.

Charles Sangster’s papers are held by the McGill Univ. Libraries, Dept. of Rare Books and Special Coll. They include letters, miscellaneous fragments of unpublished poems, and a number of manuscripts: those of “Norland echoes and other strains and lyrics”; of “The angel guest and other poems and lyrics”; of the revised Hesperus, and other poems and lyrics; and of the “miscellaneous poems” for The St. Lawrence and the Saguenay, and other poems. In addition, some correspondence and a few historical documents are in the Sangster family papers at QUA, 2030, and three of his letters are in NA, MG 29, D11.

The December 1850 issue of the Literary Garland (Montreal) carried two of Sangster’s poems, “The orphan girl” and “Bright eyes” (in new ser., 8: 543 and 567 respectively); they are the earliest published works known. In July 1855 “A ‘Thousand Island’ lyric” appeared in the Anglo-American Magazine (Toronto), 7 (July–December 1855): 111. The title of this poem was later changed to “Lyric to the isles” and it became part of “The St. Lawrence and the Saguenay.” Stanzas of Sangster’s later revisions of “The St. Lawrence and the Saguenay” were originally published in three works: two revised and four new stanzas in Morgan, Sketches of celebrated Canadians, in 1862; two revised and four new stanzas, headed “Wolfe,” in the 13 Jan. 1866 issue of the Saturday Reader (Montreal), 1 (1865–66): 297; and ten revised and twenty-seven new stanzas in the British America volume of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s anthology Poems of places (31v., Boston, 1876–79), 30.

Two poems, “Quinté” and “Niagara,” appeared in the British American Magazine (Toronto), 1 (1863): 179–81 and 234–35 respectively. The piece in honour of W. C. Bryant was published in The Bryant Festival at “The Century,” November 5, M.DCCC.LXIV., a work put out by the Century Assoc. of New York in 1865. “McEachren” appeared in the Chronicle and News (Kingston, [Ont.]), 15 July 1866. Some poems from Sangster’s two published volumes were included in W. D. Lighthall’s anthologies, Songs of the great dominion: voices from the forests and waters, the settlements and cities of Canada (London, 1889) and Canadian poems and lays: selections of native verse, reflecting the seasons, legends, and life of the dominion (London, [ 1893?]). The poem Our norland was published in pamphlet form in Toronto around 1896.

The St Lawrence and the Saguenay and other poems; Hesperus and other poems and lyrics, intro. Gordon Johnston (Toronto and Buffalo, N.Y., 1972), reprints the 1856 edition of The St. Lawrence and the Saguenay and the 1860 edition of Hesperus. Sangster’s revisions of these volumes and the two unpublished collections have been edited by Frank M. Tierney and published in Ottawa as Norland echoes and other strains and lyrics (1976); The angel guest and other poems and lyrics (1977); Hesperus and other poems and lyrics (rev. ed., 1979); and St. Lawrence and the Saguenay and other poems (rev. ed., 1984), which also includes extracts from “The rebel,” Sangster’s earliest extant manuscript.

Numerous reviews and articles on Sangster’s poems were published during his lifetime. Excerpts of contemporary reviews appear in the 1860 edition of Hesperus, which also reprints Susanna Moodie’s letter, and in Morgan, Sketches of celebrated Canadians.

George Stewart, “Charles Sangster and his poetry,” Stewart’s Literary Quarterly Magazine (Saint John, N.B.), 3 (1869–70): 334–41. Daily News (Kingston), 9 Dec. 1893. Cyclopædia of Canadian biog. (Rose and Charlesworth), vol.2. R. P. Baker, A history of English-Canadian literature to the confederation . . . (Cambridge, Mass., 1920), 159–65. A. S. Bourinot, “Charles Sangster [1822–1893],” Leading Canadian poets, ed. W. P. Percival (Toronto, 1948), 202–12; Five Canadian poets . . . (Ottawa, 1968), 12–19. E. K. Brown, On Canadian poetry (rev. ed., Toronto, 1944), 29–33. E. H. Dewart, “Charles Sangster, a Canadian poet of the last generation” in his Essays for the times; studies of eminent men and important living questions (Toronto, 1898), 38–51. W. D. Hamilton, Charles Sangster (New York, 1971). Desmond Pacey, Ten Canadian poets: a group of biographical and critical essays (Toronto, 1958), 1–33. Donald Stephens, “Charles Sangster: the end of an era,” Colony and confederation: early Canadian poets and their background, ed. George Woodcock (Vancouver, 1974), 54–61. D. M. R. Bentley, “Through endless landscapes: notes on Charles Sangster’s ‘The St. Lawrence and the Saguenay,’” Essays on Canadian Writing (Downsview [Toronto]), no.27 (winter 1983–84): 1–34. A. S. Bourinot, “Charles Sangster (1822–1893),” Educational Record of the Prov. of Quebec (Quebec), 62 (1946): 179–85. E. H. Dewart, “Charles Sangster, the Canadian poet,” Canadian Magazine, 7 (May–October 1896): 28–34. F. M. Tierney, “The unpublished and revised poems of Charles Sangster,” Studies in Canadian Literature (Fredericton), 2 (1977): 108–16.

Cite This Article

Frank M. Tierney, “SANGSTER, CHARLES,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 1, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/sangster_charles_12E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/sangster_charles_12E.html |

| Author of Article: | Frank M. Tierney |

| Title of Article: | SANGSTER, CHARLES |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1990 |

| Year of revision: | 1990 |

| Access Date: | January 1, 2026 |