Source: Link

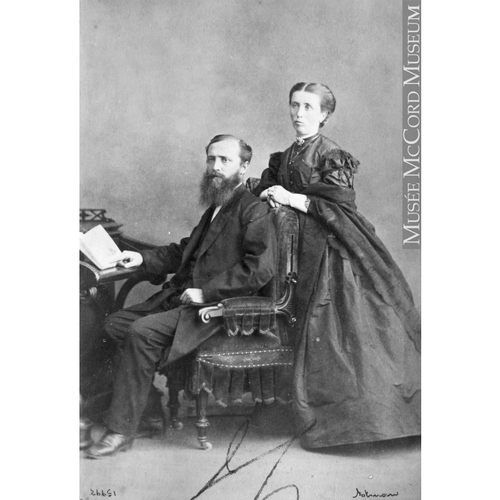

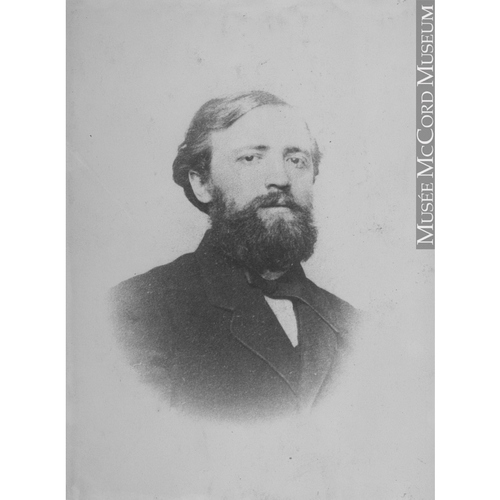

LESPERANCE (Lespérance), JOHN (in 1888 he added Talon to his name and became John Talon-Lesperance), author, journalist, editor, and office holder; b. 3 Oct. 1835 in St Louis, Mo., son of Jean-Baptiste Lespérance and Rita-Élizabeth Duchanquette; m. 20 Sept. 1866 Lucie-Parmélie Lacasse in Saint-Jean (Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu), Lower Canada, and they had three children; d. 10 March 1891 in Montreal.

Born into a family of “Creole origin,” as he described it, John Lesperance, “aged 23 months,” was baptized in St Louis on 3 Sept. 1837. In February 1845 he was enrolled in the “preparatory department” of Saint Louis University and continued to study there until 1851, when he entered the noviciate of St Stanislaus, Society of Jesus, at Florissant, Mo. He studied philosophy at Saint Louis University in 1856 and at the Jesuit college in Namur, Belgium, in 1857 and 1858. In 1859, 1862, and 1863 he taught at Saint Louis University; in 1860 and 1861, at St Joseph’s College, Bardstown, Ky. During these years he also wrote poetry and drama. One of his youthful poems was later used in a handbook of rhetoric prepared for “the lower college classes” of Saint Louis University and neighbouring Jesuit colleges. His play “Elma, the Druid martyr,” was frequently acted by students at Jesuit institutions in the St Louis area. In 1864 Lesperance enrolled in first-year theology at St John’s College (now Fordham University) in New York City, but poor health, probably an attack of the mental illness that was to recur throughout his life, forced him to return to St Louis. There, in 1865, he asked for and received a dispensation from his vows and permission “to resume life in the world.”

In later years Lesperance apparently invented various stories to explain what he did in the 1850s and 1860s. These fictions, which included periods of study at a European university and service with the Confederate army during the American Civil War, have been repeated in most biographical entries on Lesperance since his death.

Until shortly after his marriage to his first cousin in September 1866, Lesperance was living in Montreal. He then settled for some time in Saint-Jean before he moved back to the city with his family. Over the next decade he worked as a journalist for the Saint-Jean News and Frontier Advocate and the Montreal Gazette, and for the Canadian Illustrated News, which he helped edit for several years. He also contributed articles to other periodicals; “The dumb speak,” his report on new methods of teaching the dumb, for example, appeared in the Toronto Canadian Monthly and National Review in December 1872.

The 1870s marked Lesperance’s greatest output of creative writing. His poems, contributed to various periodicals, included “Abbandonata,” published in the Canadian Monthly in January 1876. “My Creoles . . . ,” a semi-autobiographical story of the Mississippi valley, was serialized in the St Louis Republican in 1878; it ran in the Canadian Illustrated News from July to November 1879. “Alma Mater,” an article celebrating the golden jubilee of Saint Louis University, appeared in the Republican on 13 Sept. 1879. Most of Lesperance’s creative work, however, focused on his adopted homeland. In the early 1870s he wrote three short stories on Canadian subjects for the Canadian Illustrated News. The longest, “Rosalba . . . ,” by Arthur Faverel, one of Lesperance’s pseudonyms, centred on the rebellion of 1837–38; it was serialized in March and April 1870. To help celebrate the centennial of the American revolution in 1876, Lesperance composed a play, One hundred years ago . . . , which was published in Montreal that year. Dealing with the last years of the war, it dramatizes the mixed motives and loyalties of citizens of the Thirteen Colonies during the rebellion. Probably for the same centennial, Lesperance also wrote what became his most popular work, The Bastonnais. . . . Serialized in the Canadian Illustrated News from January to September 1876 and published in volume form in 1877, this novel is set against the background of the attempt by American forces to capture Quebec in 1775–76. Translated into French and published in that language at least once, “Rosalba,” One hundred years ago, and The Bastonnais are typical of Lesperance. Each deals with an event in North American history. Each focuses on the crises this occurrence causes for people of different nationalities on the same, or a different, side, and analyses these tensions by means of at least one courtship. And each, particularly the two works of fiction, describes local customs and legends. Both works of fiction, furthermore, are historical romances, a form that Lesperance called “one of the most efficient means of popular instruction and entertainment.”

From the mid 1870s the dissemination of information about Canadian history and literature became increasingly important for Lesperance. In February 1877, in a speech to the Kuklos Club of Montreal, a club for English-language journalists that he had helped found in 1875, Lesperance, a voracious reader, reviewed “The literary standing of the dominion.” “Different men have different ways of testing the progress of a country,” he began. “My test is the progress of its literature.” He then described briefly several Canadian authors and works. Among writers in French he mentioned François-Xavier Garneau* and his Histoire du Canada . . . , Philippe-Joseph Aubert* de Gaspé, author of Les anciens canadiens, and James MacPherson Le Moine*, “a gentleman equally at home in the English language.” Susanna Strickland* Moodie’s Roughing it in the bush . . . and Life in the clearings . . . , he commented, “have a force of realism about them which accounts for their reputation both in England and the United States.” Charles Heavysege*, Charles Mair*, and Charles Sangster were “true Canadian poets.”

Lesperance’s encouragement of Canadian talent led him to publish one particular poet, in the Canadian Illustrated News of 10 May 1879. He recalled the story in a speech in 1884. “I received a small copy-book containing a number of short poems, written out in a schoolboy’s hand. . . . I at once plucked out . . . a sonnet [“At Pozzuoli”] and published it . . . . I felt sure that we should soon hear from this New Brunswick boy again. And so we did. In 1880, there was published in Philadelphia a dainty little volume, entitled Orion, and other poems.” Its author was Charles George Douglas Roberts*.

In the late 1870s Lesperance, “sapped by overwork,” probably had another breakdown, which led to his resignation from the Canadian Illustrated News in 1880. Recovering, he worked in 1881 for the Montreal Gazette and Star. For several years in the 1880s he contributed “Ephemerides,” a Saturday column, to the Gazette; William Douw Lighthall*, his friend and fellow littérateur, described the series as “short paragraphs, containing scraps of history or antiquarianism, quotations, musings, sometimes poetry of his own or of others, classical references, an occasional announcement of a new book, and even a cookery recipe or two, the whole being signed ‘Laclède,’ after [Pierre de] Laclède Liguest, the founder of his native city, St Louis.” The “attraction” of the series “lay almost altogether in its unveiling of the individuality of one of the dearest, most idealistic men who ever lived or wrote.”

From 1882 until 1886 Lesperance was also provincial immigration agent in Montreal. Throughout the decade he continued to encourage the study and creation of Canadian history and literature. A founding member of the Royal Society of Canada in 1882, he spoke at its annual meetings on such topics as “The literature of French Canada” (1883), “The poets of Canada” (1884), “The analytical study of Canadian history” (1887), and “The romance of the history of Canada” (1888). In the last, Lesperance, who had become convinced that he was a relative of Jean Talon*, called him “perhaps the most useful man who ever wrought in Canada.” From then until his death, Lesperance became Talon-Lesperance. In 1888, for example, as Talon-Lesperance he contributed a biography of Joseph-Adolphe Chapleau arid one of Pierre-Joseph-Olivier Chauveau* to the series on “Prominent Canadians” running in the Toronto Week.

In July 1888 Talon-Lesperance, described as “well known throughout Canada as an erudite, scholarly, and interesting writer,” joined the newly established weekly of George-Édouard Desbarats, the Dominion Illustrated, as director of its “literary portion.” From July to December he contributed short stories, poetry, articles, and a variety column. He was president of the Society for Historical Studies, and in 1889, founding vice-president of the Society of Canadian Literature. He continued to busy himself with the Royal Society of Canada. On 27 Jan. 1889, for example, he reported to his friend George Taylor Denison* that he had voted for Charles Mair’s membership in the society. In the same letter Lesperance wrote that he had published, “for the first time,” Mair’s “The last bison” and “Kanata” in the Dominion Illustrated. His own “Empire first” appeared in Songs of the great dominion . . . (1889), the important anthology of Canadian poetry that Lighthall selected and edited.

On 17 July 1888 Rita, Talon-Lesperance’s favourite child, died. The shock eventually undermined his already fragile health. In February 1889 he was seized with an “insidious paralysis attended with gentle delusions,” as Lighthall described the illness. He died on 10 March 1891, and after a funeral service at the Roman Catholic church of Notre-Dame was buried in Côte-des-Neiges Cemetery on 13 March.

John Lesperance is on the whole not well known today. Yet he published prolifically. He explored Canadian customs, history, and legend in his own writing. In the 1870s and 1880s especially, when the new dominion was creating a national identity, he worked hard to encourage others to figure forth in their works the people, events, and themes that formed – and form – the “romance” and “philosophy” of Canadian culture.

The works of John Lesperance include the novel “Rosalba; or faithful to two loves: an episode of the rebellion of 1837–38,” serialized under the pseudonym Arthur Faverel in the Canadian Illustrated News (Montreal), 19 March–16 April 1870. It was translated into French by Emmanuel-Marie Blain* de Saint-Aubin as “Rosalba ou les deux amours: épisode de la rébellion de 1837” and published in L’Opinion publique, 27 April–8 June 1876, and in Le Monde illustré (Montréal), 1898–99. Lesperance also wrote One hundred years ago; an historical drama of the War of Independence in 4 acts and 20 tableaux (Montreal, 1876), a play known in French as Il y a cent ans; drame historique de la guerre de l’Indépendance, en 4 actes et 20 tableaux. His novel The Bastonnais: a tale of the American invasion of Canada in 1775–76 (Toronto, 1877) came out originally in the Canadian Illustrated News, January–September 1876. A French translation, the work of Aristide Piché, was first published in La République (Boston) in 1876; Les Bastonnais was reissued in the Rev. canadienne in 1893–94, and in Montreal in 1896 and in 1925. “My Creoles; a story of St Louis and the southwest twenty-five years ago” was published in the Republican (St Louis, Mo.) in 1878, and reprinted in the Canadian Illustrated News, July–November 1879.

ANQ-M, CE1-51, 20 juill. 1888, 13 mars 1891; CE4-10, 20 sept. 1866. NA, MG 29, E29, 3–4, 27 Jan. 1889. Dominion Illustrated (Montreal), 7, 28 July 1888; 21 March 1891. Gazette (Montreal), 11 March 1891. DOLQ, vol.1. Oxford companion to Canadian lit. (Toye), 451–52. The evolution of Canadian literature in English . . . , ed. M. J. Edwards et al. (4v., Toronto and Minneapolis, Minn., 1973), 2: 16–24. Songs of the great dominion: voices from the forests and waters, the settlements and cities of Canada, ed. W. D. Lighthall (London, 1889). Léon Trépanier, On veut savoir (4v., Montréal, 1960–62), 4: 83. C. M. Whyte-Edgar, A wreath of Canadian song, containing biographical sketches and numerous selections from deceased Canadian poets (Toronto, 1910), 147–52. M. J. Edwards, “Essentially Canadian,” Canadian Literature (Vancouver), no.52 (spring 1972): 8–23. “John Lesperance,’52,” Fleur de Lis (St Louis), 3 (1902): 174–83.

Cite This Article

Mary Jane Edwards, “LESPERANCE (Lespérance, Talon-Lesperance), JOHN,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 1, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/lesperance_john_12E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/lesperance_john_12E.html |

| Author of Article: | Mary Jane Edwards |

| Title of Article: | LESPERANCE (Lespérance, Talon-Lesperance), JOHN |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1990 |

| Year of revision: | 1990 |

| Access Date: | January 1, 2026 |