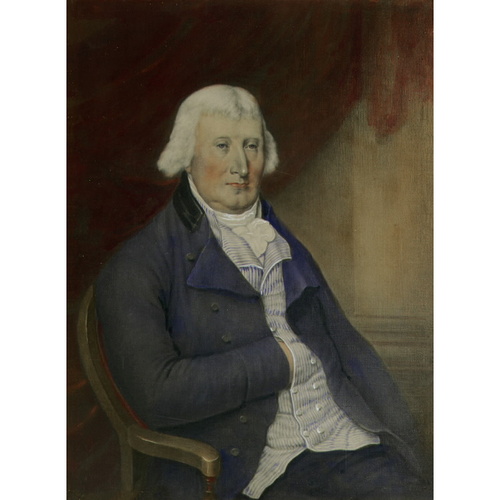

RUSSELL, PETER, office holder, politician, and judge; b. 11 June 1733 in Cork (Republic of Ireland), only son of Richard Russell and his first wife, Elizabeth Warnar; d. 30 Sept. 1808 in York (Toronto), Upper Canada.

Peter Russell was the son of an improvident Irish army officer who claimed without much evidence to be related to the Duke of Bedford. His formal education consisted of boarding for four years with the Reverend Barton Parkinson, first at Cork and then at Kinsale, where he shared studies and a bed with his first cousin William Willcocks and where he became “a very pretty Schollar” according to Parkinson. For six months in 1751 he attended St John’s College, Cambridge, but his university career ended abruptly because of his extravagance. He considered entering the army, navy, or trade; he chose the army because he thought he was too weak for the navy and too old for his first choice, trade. Unfortunately there was neither enough money to buy his commission nor enough influence to get one without purchase; Russell had to wait for the Seven Years’ War to enter the army.

In 1754 Major-General Edward Braddock, commanding officer of Russell’s father’s regiment, the 14th Foot, and newly appointed commander-in-chief in North America, advised Russell to go there as a volunteer because chances of a commission were good. Russell arrived in South Carolina on 21 May 1755, but delayed joining Braddock’s army because of sickness, difficulties in communication, and high living. In July he heard of Braddock’s defeat and death, and of his own appointment as an ensign in the 14th, still at Gibraltar. Russell stayed in North America until November, finally arriving in Gibraltar the following May. From July to October 1756 he took part in the second abortive attempt to relieve the garrison on Minorca [see John Byng*]. After becoming a lieutenant on 8 May 1758, Russell returned to England, became dissatisfied, and “quitted his commission in a pet.” Realizing, however, that he was too old to begin a new career he accepted Lieutenant-Colonel John Vaughan’s offer of a lieutenancy in a new regiment, the 94th Foot, raised for service in North America. Commissioned on 12 Jan. 1760, Russell sailed for North America on 26 August, serving as adjutant and paymaster mostly in the West Indies until the reduction of the regiment on 24 Oct. 1763.

In August 1763 Russell arrived in New York owing more than £1,000 after a disastrous final week of gambling in Martinique. Successful gambling in New York enabled him to settle his army accounts; even greater success in Virginia brought him a 462-acre tobacco plantation 42 miles west of Williamsburg. Here Russell lived on half pay for almost eight years, hiding from his creditors and longing for capital to enter the lucrative slave trade. To raise funds he once more tried gambling, but again he lost; to pay his Virginia debts he had to sell his estate and return to England. Arriving home on 14 Oct. 1771, he was beset with demands for payment of his Martinique debts, and in November 1773 he was forced to fly to the Netherlands where he stayed for ten months before returning. After a humiliating residence within the bounds of Fleet prison he was discharged on 7 Oct. 1774 under the Insolvent Debtors Relief Act.

War in America once more gave him an occupation. On 15 Aug. 1775 Russell was commissioned lieutenant in an additional company of the 64th Foot raised for the war. For several years he recruited in Ireland; finally on 25 Feb. 1778 he sailed for America because promotions were given only to officers there. He succeeded to the captain-lieutenancy of the 64th on 18 August and in October became an assistant secretary to the commander-in-chief, Sir Henry Clinton. After taking part in the capture of Charleston, Russell was appointed judge of the Vice-Admiralty Court of South Carolina on 19 May 1780 by Clinton, but this appointment was disallowed and given to a lawyer with prior claim. On 19 December Russell finally received his captaincy in the 64th. He sold it nine months later at an inflationary price of £2,000 just before leaving with Clinton on his unsuccessful attempt to relieve Lieutenant-General Charles Cornwallis at Yorktown, Va. On 1 Jan. 1782 Clinton appointed him superintendent of the port of Charleston and on 15 April captain in the Royal Garrison Battalion, but Clinton’s career in America was over, and on 13 May 1782 he and Russell sailed for England.

Because of the sale of his commission Russell for the first time in his life had money, which he showered on his father, his half-sister Elizabeth*, and even the mendicant Willcocks family. By 1786, when his father died leaving him only debt and the responsibility for Elizabeth, Russell was once more a poor man begging unsuccessfully for insignificant posts. Since his return to England he had helped Clinton in his controversy with Cornwallis and had written a monumental history of the American campaigns attacking Cornwallis. To protect Russell it was decided to publish it under Clinton’s name, although as Clinton wrote, “You have already uttered too many galling truths to be forgiven.” Russell’s book was too controversial to be published, and it finally appeared under Clinton’s name in 1954.

In 1790, then, when Upper Canada was about to come into existence, Russell was struggling to support himself and Elizabeth on a captain’s half pay, his patron having lost all influence through his quarrel with Cornwallis. Clinton and other fellow officers, including Simcoe whom Russell had met in America, still tried to help, and in the summer of 1790, when Simcoe was promised the lieutenant governorship of Upper Canada, it seemed as if Russell too was to be fortunate. In October he accepted the position of secretary to Andrew Elliott, who was going as British minister to the United States, but Elliott eventually declined the posting, destroying Russell’s prospects. Simcoe then recommended Russell to Home Secretary Henry Dundas on 12 Aug. 1791 for appointment as Upper Canadian receiver and auditor general with seats on the Executive and Legislative councils. The appointments were approved in September, although Russell’s commission was not issued until 31 Dec. 1791 and not received until a year later. He still hoped for something better since he would have to give up his half pay in return for only £300 a year, but when nothing materialized he left England in the spring with his half sister, Chief Justice William Osgoode*, and Attorney General John White*, arriving at Quebec on 2 June 1792.

When Russell arrived in Upper Canada he was 59, much older than most of his colleagues. His closest friends were probably the ablest members of Simcoe’s government – Osgoode, White, and Surveyor General David William Smith* – but he disagreed with White and Smith in their criticism of Simcoe’s autocratic methods. With Simcoe himself he was on good if not cordial terms. He was a faithful member of the councils and did his share in establishing the working machinery of government. Because all senior government officers were ill-paid, bickering over their relative portion of fees began early and continued for many years; in this squabbling Russell also did his share.

In the beginning there were only four executive councillors, with Russell’s name the last on the list. In 1794, however, after Chief Justice Osgoode was transferred to Lower Canada and only one judge was left on the Court of King’s Bench in Upper Canada, it was Russell whom Simcoe appointed a temporary puisne judge, with a salary of £500 a year. On 6 July 1795 Russell took over Osgoode’s former position as speaker of the Legislative Council. On 1 Dec. 1795 Simcoe requested leave of absence, and recommended that Russell, “the senior Executive Counsellor, (not a Roman Catholick) and . . . in all respects the proper person” be chosen to administer the government. Russell was appointed administrator on 20 July 1796, and on the following day Simcoe left York. At 63, Russell was in a position of authority for the first time in his life.

Russell’s administration began auspiciously with the peaceful transfer of six border posts from the British to the Americans under the terms of Jay’s Treaty. Even the American occupation of Fort Niagara (near Youngstown), N.Y., within firing range of Fort George (Niagara-on-the-Lake), went off smoothly without the repercussions that were feared. It was a good beginning but Russell’s early days in office were marred by the discovery that Simcoe had left him only 12 official documents, taking with him all his other papers including his correspondence with London and Quebec. Throughout his administration, the unfortunate Russell was ignorant of the intentions of both Simcoe and the British authorities on every aspect of government.

At this period the granting of land was the most important responsibility of government. By 1796 the machinery for handling it was grinding slowly and capriciously, not keeping up with the demand for crown grants or for the transfer of property. There was justifiable fear that speculators were acquiring too much land. Russell had always been interested in the problem: 25 years earlier, on his return from Virginia, he had tried to interest the government in his program of reform for land-granting abuses there. In Upper Canada he tightened up the system, closing loopholes and making it more efficient. The loyalist lists were revised; claims for privilege through family relationships were restricted; the surveyor general’s office was to keep a list of undesirables; every petitioner was to state clearly what land he had already been granted and this declaration was to be checked; every petition was to be approved by the lieutenant governor or the administrator; no land was to be transferred until the deed had been issued; the system for the collection of fees was revised.

Because of previous irregular land transfers an act was passed in June 1797 to secure land titles, establishing a land commission to settle individual cases. The Heir and Devisee Commission reported the following month on the grants of townships to proprietors who had agreed to settle and improve them. Simcoe had already rescinded township grants to several proprietors including Russell’s cousin, William Willcocks, who had accomplished nothing. Russell went even further and rescinded all township grants, giving compensation for actual settlement only. The most famous instance involved William Berczy, who lost Markham Township. His vehement protest was in vain for “all the Branches of this Government,” according to Russell, “have but one opinion” and thus settlement by township proprietors ended. During Russell’s administration there was one other attempt at mass settlement, wished on him by the British government. In the autumn of 1798, 40 French émigrés led by Joseph-Geneviève Puisaye*, Comte de Puisaye, arrived and were settled up Yonge Street. Russell obediently followed instructions to assist this scheme, but it was doomed to failure from the outset.

Another vexing problem concerning land was the anomalous status of the large tract on the Grand River belonging to the Six Nations Indians. Joseph Brant [Thayendanegea], the Indian leader, asserted the Indians’ right to sell their land; however, Simcoe and Russell maintained that it had been given in perpetuity and could not be alienated. After Simcoe’s departure Brant became more insistent; Russell temporized, writing desperately to London for instructions when Brant sold 381,480 acres and demanded that deeds be issued to the purchasers. During the winter of 1796–97 there were rumours of unrest among the Indians on the Mississippi River, so that the continued loyalty of the Upper Canadian Indians was vital. On 29 June 1797 the Executive Council recommended that Russell come to an immediate decision without waiting any longer for instructions from London. Accordingly Russell agreed to issue the deeds. On 15 July, before the details had been settled with Brant, the dispatch from London finally arrived instructing Russell not to accede to Brant’s request; the British government would give the Indians an annuity in lieu of permission to sell their land. Brant refused this offer, forcing Russell to disobey his instructions and to issue the deeds on condition that no more land be alienated. In the midst of this controversy Russell learned that responsibility for Indian affairs in Upper Canada had been transferred to him from Quebec on 15 Dec. 1796.

Until the arrival of the new chief justice, John Elmsley, on 20 Nov. 1796 Russell’s Executive Council was weak. Unfortunately Elmsley, although strong, opposed Russell almost continually. Their first major battle was over the seat of government. Before Simcoe left he had moved his capital from Newark (Niagara-on-the-Lake) to York, despite the lack of enthusiasm of most government officials, including Russell. Elmsley objected vigorously, but Russell doggedly followed Simcoe’s directions, and met his first parliament in York in June 1797. He spent much effort in improving the capital: the New Town was surveyed and opened west of Simcoe’s original site; a primitive zoning plan was established; work on public buildings was accelerated; plans were made for adequate defence; some local self-government was granted; police-force regulations were proposed (but blocked by Elmsley); better transportation links with other parts of the province were provided by extending Simcoe’s Dundas and Yonge streets into the town and by building the Danforth Road east to Kingston.

Russell’s reappointment of himself to the Court of King’s Bench was also sharply criticized by Elmsley. Though the reason for his holding the judgeship was no longer valid, Russell kept reissuing his own commission, the last time being on 17 March 1798. He probably did it for the salary; as administrator he received no additional remuneration. With no legal training Russell was vulnerable to ridicule on the bench while at the same time he was breaching the principle of separation of executive and judicial powers. Finally he was ordered to give up the judgeship in return for half Simcoe’s salary and fees.

Until the spring of 1798 Russell had expected Simcoe’s return to Upper Canada. Thereafter he hoped, without much expectation, to become governor, but in June 1799 he heard of Peter Hunter’s appointment and that August Hunter arrived in Upper Canada. The new lieutenant governor was much impressed by Elmsley, so that Russell’s influence as well as his position was greatly diminished. He remained receiver general and was a member of the small committee that governed the province during Hunter’s absences, but he had little power. Simcoe had asked that some provision be made for him because he was very old, but nothing was done. After Hunter’s death in 1805 Alexander Grant was appointed administrator because his name preceded Russell’s on the official list; Russell protested in vain. Although he owned thousands of acres of land in Upper Canada (as an executive councillor he was given 6,000 acres) he could not find purchasers and could not therefore afford to return to England. He remained in York, tired, sick, and old, still interested in scientific experiments which he had begun long ago in Virginia, still conscientiously doing his duty as receiver general. At his death his estate, which was rapidly increasing in value, passed to Elizabeth, who left it to William Willcocks’s daughters in 1822.

Russell has never been considered one of the great men of Ontario. Although later criticism has rather unjustly charged him with greed for land, his contemporaries objected to his greed for fees and offices. As administrator he was cautious, practical, capable, and painstaking. Unlike Simcoe he had little imagination, sometimes had difficulty making decisions, and was willing to devote much thought and effort to detail. Russell, however, was administrator, not lieutenant governor, and he had neither the authority nor the security of governorship. Yet the record of legislation during his administration is impressive, not for great statutes but for those which corrected abuses, improved conditions, or made the machinery of government work more smoothly. Russell was not a great man and his abilities may have been pedestrian, but his accomplishments were very real.

Some of Peter Russell’s early correspondence has been published in “The early life and letters of the Honourable Peter Russell,” ed. E. A. Cruikshank, OH, 29 (1933): 121–40, while a comprehensive collection of his official correspondence as administrator of Upper Canada is available in Corr. of Hon. Peter Russell (Cruikshank and Hunter). The journal he kept during the Charleston campaign appears as “The siege of Charleston; journal of Captain Peter Russell, December 25, 1779, to May 2, 1780,” ed. James Bain, American Hist. Rev. (New York and London), 4 (1898–99): 478–501.

AO, ms 75;

Cite This Article

Edith G. Firth, “RUSSELL, PETER,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 5, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 20, 2024, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/russell_peter_5E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/russell_peter_5E.html |

| Author of Article: | Edith G. Firth |

| Title of Article: | RUSSELL, PETER |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 5 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1983 |

| Year of revision: | 1983 |

| Access Date: | December 20, 2024 |