Source: Link

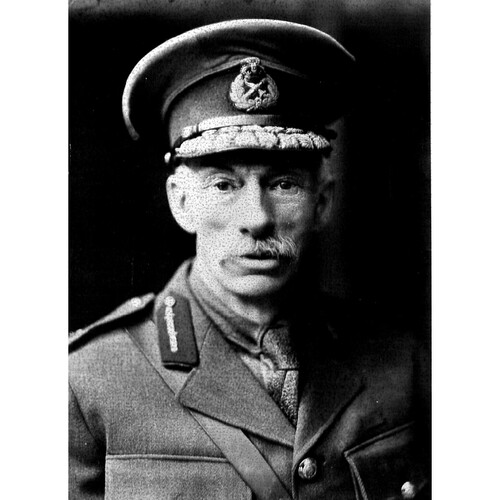

CRUIKSHANK, ERNEST ALEXANDER, militia officer, author, historian, civil servant, and army officer; b. 29 June 1853 or 1854 in Bertie Township, Upper Canada, third child and only son of Alexander Cruikshank and Margaret Milne; m. first 26 June 1879 Julia E. Kennedy (d. 5 June 1921) in Buffalo, N.Y.; m. secondly 8 Jan. 1923 Matilda Jane Murdie in Ottawa; no children were born of either marriage; d. there 23 June 1939 and was buried in Beechwood Cemetery.

Ernest Alexander Cruikshank’s parents emigrated from Scotland in 1835 and eventually settled in Bertie Township, Welland County. There they established a farm, built a brick home, and earned an increasingly comfortable income from properties that they acquired and then leased to local farmers. The Cruikshanks had three children, of whom Ernest was the youngest by 13 or 14 years. He began his education at the public school in Fort Erie, and in 1866 he started attending the grammar school in St Thomas, where he lived with his sister Eliza Ann and her husband. There Ernest became friends with future historian James Henry Coyne*, who served with a militia unit, the St Thomas Rifle Company, which was mobilized but did not see action during the Fenian raids of that year. The association with Coyne and the mentorship of William Napier Keefer, headmaster of the school and drill sergeant of the local student rifle brigade, fostered Cruikshank’s lifelong interest in military history, especially the battles on the Niagara frontier during the War of 1812. He attended Toronto’s Upper Canada College as a boarder from 1869 to 1870, but never went to university.

After leaving school, Cruikshank moved to the United States, where he worked as a correspondent for several daily newspapers. He had a gift for learning languages and was employed by an American commercial firm as a professional translator of French, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, German, Dutch, Danish, and Swedish. In about 1874 Cruikshank returned to the family farm in Bertie Township, where he made his living as a farmer and landlord. In 1879 he married Julia Kennedy, originally of Scranton, Pa, who had lived most of her life on the American side of the Niagara peninsula. A witty and well-read woman, Julia likely had an influence on her husband’s intellectual development. A journal she kept in the early 1900s, which was later published as Whirlpool Heights: the dream-house on the Niagara River (London, 1915), indicates that they both enjoyed literature, solitude, and the outdoors. Their marriage, which her journal entries suggest was an affectionate one, would last 42 years, until her death in 1921.

In the late 1870s Cruikshank became prominent in local politics and public administration, being elected to serve as Bertie Township’s assessor (1876–77) and treasurer (1877–78), and as reeve of Fort Erie (1878–82, 1885–87, and 1889–93). In 1886 he was also warden for Welland County. Cruikshank championed prison reforms, the protection of game animals, and the development of public access to Niagara Falls. He was clerk of the district court for many years, before moving to the town of Niagara Falls in 1904 to become police magistrate for the community and the surrounding area.

On 28 Sept. 1877, soon after entering public life, Cruikshank had joined the 44th (Welland) Battalion of Infantry as an ensign. The Canadian militia was as much a social and political organization as it was an armed force, but he took his military duties seriously. Only 11 years earlier the Niagara frontier had been breached by the Fenians, and since 1871, when the British military presence in the dominion was reduced to a garrison located in Halifax, a tiny professional force and the militia had been Canada’s only land-based defences. After becoming a lieutenant in 1881 and a first lieutenant a year later, in 1883 Cruikshank was given command of the battalion’s No.4 Company, stationed at Fort Erie; he was made captain the following year. He took an active part in the life of the regiment and taught courses for junior recruits at the School of Military Instruction in Toronto. In 1894 he was promoted brevet major (raised to full major in 1897), and on 25 Feb. 1899 he was placed in command of the 44th, at the rank of lieutenant-colonel. Five years later he relinquished this position and moved to Niagara Falls. On 23 March 1905 he became the 44th’s honorary colonel, and on 13 Oct. 1905 he took over the 5th Infantry Brigade, headquartered in Niagara Falls, which he led until 1 May 1909. After his death Cruikshank would be described by one contemporary, Winnipeg Free Press writer Harold Moore, as “a remote, a diffident, personality in a lanky frame imbued with an instinct for modern soldiering.” He never saw combat: Cruikshank was not part of the military effort to put down the North-West rebellion in 1885, and although he volunteered twice to serve in the South African War (1899–1902), he was turned down both times.

Cruikshank was a student of military history, especially the Canadian campaigns of the War of 1812. He published his first book, A historical and descriptive sketch of the county of Welland … (Welland, Ont., 1886) while serving as warden of the county. Soon afterwards he became involved in historical societies in southwestern Ontario, giving papers on various topics, notably the War of 1812 battles of Queenston Heights, Lundy’s Lane, and Beaver Dams, and the siege of Fort Erie. Several of these papers were developed into books that would be published in multiple editions. Shy and reserved, Cruikshank does not appear to have enjoyed the sociable mingling that typically followed his public talks: Julia notes in Whirlpool Heights that on one occasion when members of the Ontario Historical Society crowded around him to praise his lecture, “he looked as if he wished he were in the woods.”

As a historian Cruikshank was devoted to a British conception of Canadian history that emphasized military events and the role of the United Empire Loyalists in fostering an imperial identity. His work won him much praise among contemporary historians: in 1899 he was elected an honorary member of the Ontario Historical Society, and in 1906 he became a fellow of the Royal Society of Canada. He was active in the Historic Landmarks Association, the forerunner of the Canadian Historical Association, as was his friend James Coyne. One of Cruikshank’s most significant contributions as a historian was as a collector and compiler of documents, most notably so in his nine-volume series, The documentary history of the campaign upon the Niagara frontier … (Welland, 1896–1908). He resigned as police magistrate in 1908 to become keeper of the military documents at the Public Archives of Canada (PAC), headed by Arthur George Doughty. At the PAC Cruikshank indexed British records pertaining to Canada’s early military history. His work would result in the publication of the Inventory of the military documents in the Canadian Archives (Ottawa, 1910) and a supplemental collection, Documents relating to the invasion of Canada and the surrender of Detroit, 1812 (Ottawa, 1912).

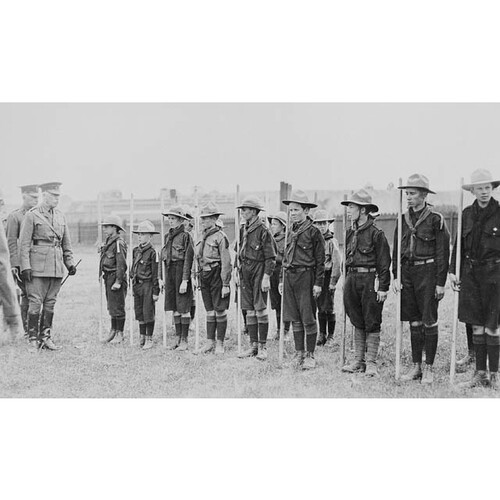

In May 1909, after spending only a year at the PAC, Cruikshank joined Canada’s small Permanent Force and moved to Calgary, where he assumed command of Military District No.13 (Alberta and the District of Mackenzie). These districts provided a basic organizational structure for the militia and the Permanent Force. Cruikshank was tireless in his efforts to improve soldiers’ training and efficiency. Writer Harold Moore remembered: “No one worked more incessantly in camps where few could be older than himself … his instructional talks to officers were vivid … his inclination to efface himself curiously created a pervasive influence among the troops encamped under his command.” Cruikshank also took an active interest in intelligence gathering. Between 1910 and 1912 he made secret visits to training camps in the United States and submitted reports on American military activities to the chief of the general staff of the Canadian militia in Ottawa.

On 1 March 1917, in the aftermath of local gossip and lawsuits against the federal government for property damage, Cruikshank accepted a position with the Department of Militia and Defence in Ottawa, where he compiled historical records relating to the Canadian Expeditionary Force. His transfer from the command of a military district to a non-command post in which he organized papers must have been humiliating, but he took solace in the fact that it allowed him to return to studying history. At Militia and Defence headquarters he sorted and arranged records as he had done at the PAC. In April 1918 he was made full brigadier-general and assigned to special duty with Sir Albert Edward Kemp*’s Ministry of the Overseas Military Forces. In this capacity Cruikshank spent three months visiting England and the battlefields of France. On 15 November, four days after the armistice, he was made director of the newly established Army Historical Section.

During his time at Militia and Defence headquarters, Cruikshank contemplated writing an official history of Canada’s involvement in the First World War. By the end of 1918 there were three organizations competing for jurisdiction over such a work: the Canadian War Narrative Section under Sir Arthur William Currie’s authority at Canadian Corps Headquarters in France; the Canadian War Records Office under Lord Beaverbrook [Aitken*] in London, England; and Cruikshank’s Army Historical Section in Ottawa. According to historian Tim Cook, Cruikshank, unlike either Currie or Aitken, believed that an official account had to be set within the larger political and historical context of Canada’s imperial ties to Great Britain. He thus began working on a multi-volume record of the Canadian militia and Britain’s military forces in Canada since the Seven Years’ War.

With this admirable intention, Cruikshank followed his usual methodology of compiling massive inventories of documents and reprinting only a few selections in combination with short narrative overviews. But when he completed the first four volumes (the first three of which were published), having drafted several more, senior officers were dissatisfied with his work. By framing his chronicle of the First World War within the context of Canada’s long-standing connection to Britain, Cruikshank was emphasizing continuity rather than change. In contrast Currie’s headquarters had produced and published a narrative account of the Last Hundred Days campaign that glorified the role of the Canadian Corps in general, and that of Currie in particular. Not surprisingly, Currie did not approve of Cruikshank’s fourth volume, which covered Canada’s involvement in the First World War through to the end of the second battle of Ypres. Writing on 12 Jan. 1921 to James Howden MacBrien, chief of the general staff of the militia, Currie remarked: “One feels that it was necessarily written by a man whose absence from the operation deprived him of the power of living the events. It lacks fire and imagination and impressiveness.” MacBrien recommended that Cruikshank retire and then promoted Colonel Archer Fortescue Duguid to replace him as director of the Army Historical Section as well as author of the official history.

By the time of his retirement from the army, Cruikshank had already found a place for his talents as a historian and antiquarian: the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada (HSMBC). Created in 1919 by the Union government of Sir Robert Laird Borden, the board was supposed to designate historical landmarks and take over authority from other federal departments for maintaining old forts and important public works. The absence of a clear mandate and adequate funding, however, limited the HSMBC’s activities to selecting historically significant sites for commemoration. Cruikshank served as the first chair, a position he held for 20 years. In May 1939, when he chaired his final meeting, he reported that the board had erected more than 294 plaques, most of them in Ontario and Quebec. In this way Cruikshank and his old friend James Coyne, who worked alongside him on the board, took leading roles in shaping the public memory of the country’s history, focusing primarily on sites related to the loyalists, the fur trade, and Canada’s British military history, especially the War of 1812.

During the last two decades of his life, Cruikshank continued to publish history, producing edited collections of the papers of John Graves Simcoe* and Peter Russell* for the Ontario Historical Society, as well as The settlement of the United Empire Loyalists on the upper St. Lawrence and Bay of Quinte in 1784: a documentary record (Toronto, 1934). His last two books were The life of Sir Henry Morgan with an account of the English settlement of the island of Jamaica (1655–1688) (Toronto, 1935) and the story of the spy John Henry*, The political adventures of John Henry: the record of an international imbroglio (Toronto, 1936). In the spring of 1939 Cruikshank fell ill with pleurisy after inspecting several HSMBC sites during a rainstorm; he died in Ottawa on 23 June. His pall-bearers included Colonel Duguid, his replacement as the author of the abortive official history of the Canadian Expeditionary Force, and Colonel John Grant Rattray, a former commanding officer of Calgary’s 10th Infantry Battalion. Cruikshank was buried in Beechwood Cemetery.

Although his body of work earned him accolades in his own lifetime, Ernest Alexander Cruikshank’s scholarship was viewed more harshly by later historians. In 1965 his principal biographer, William David McConnell, concluded that Cruikshank was a dogged researcher but an unimaginative thinker and a poor writer whose books were little more than compilations of primary documents. Fifty years later historian Alan Gordon made a similar assessment: “Certainly he was never the most skilled or consistent practitioner of a narrative approach to history. Indeed, he does not seem to have thought about it much beyond the historian’s obligation to tell an accurate story in the proper order.” Nevertheless, Cruikshank was able to popularize an interpretation of Canadian history that celebrated the country’s British connection and military heritage, and which resonated long after his death.

Ernest Alexander Cruikshank was a remarkably prolific historian. Some indication of the sheer volume of his work is provided in Ernest Green, “In memoriam: Ernest Alexander Cruikshank,” Ont. Hist. Soc., Papers and Records (Toronto), 33 (1939): 5–9, which states that “he was the author of numerous books and pamphlets and contributed hundreds of articles to military and historical publications in Canada, the United States and Great Britain.” In addition to the books and collections that have been specified in the text above, some of his most important works, which were published in Welland, Ont., unless otherwise stated, include: The battle of Lundy’s Lane, 1814: an address delivered before the Lundy’s Lane Historical Society, October 16th, 1888 (1888; 2nd ed., 1891); The fight in the beechwoods: a study in Canadian history (1889; 2nd ed., 1895); Queenston Heights (1890; 2nd ed., 1891; 3rd rev. ed., 1904); The battle of Lundy’s Lane, 25th July, 1814: a historical study (3rd ed., 1893); The story of Butler’s Rangers and the settlement of Niagara (1893); Drummond’s winter campaign, 1813 ([1895?]; 2nd ed., [1900]); The siege of Fort Erie, August 1st–September 23rd, 1814 (1905); and Camp Niagara: with a historical sketch of Niagara-on-the-Lake and Niagara camp (Niagara Falls, Ont., 1906). Cruikshank also edited The correspondence of Lieut. Governor John Graves Simcoe, with allied documents relating to his administration of the government of Upper Canada (5v., Toronto, 1923–31), and, with A. F. Hunter, The correspondence of the Honourable Peter Russell, with allied documents relating to his administration of the government of Upper Canada … (3v., Toronto, 1932–36).

Volume 1 of the Ernest Alexander Cruikshank fonds at LAC (R3261-0-5) consists of general correspondence; most useful is that pertaining to the military (1910) and James Coyne (1895–1903). Volumes 2 to 31 contain manuscripts and notes for his historical work, including his years with the Army Hist. Section; volume 31 also contains the minutes, agendas, and reports from the meetings of the Hist. Sites and Monuments Board of Can. for 1939. Volume 32 includes a diary from 1918, review clippings about his later books, copies of obituaries, and other personal papers. Military district records (R112-137-7, vols.4693–758) cover his time as commander of Military District No.13. On the Calgary riots see RG24-C-1-a, vol.1255, file HQ-593-1-86, file pt.1 (Investigation of riot caused by CEF troops at Calgary, Alberta). Cruikshank’s First World War service record can be found in RG 150, Acc. 1992-93/166, box 2187-34. His activities at the Army Hist. Section are documented in R112-134-1, vols.1732–65, 1902–9, 1883–1901, 1810–50; and his service at the Hist. Sites and Monuments Board can be traced in the board’s minutes in RG84-A-2-a, vol.2329, file U325, mfm. T-16531. See also R7180-0-5 (Arthur William Currie fonds), vol.11, file 34, Currie to MacBrien, 12 Jan. 1921.

Calgary Daily Herald, 12 Feb. 1916. Winnipeg Free Press, 20 July 1939. Can., Dept. of Militia and Defence, Militia list (Ottawa), 1899–1917. Tim Cook, Clio’s warriors: Canadian historians and the writing of the world wars (Vancouver and Toronto, 2006). Alan Gordon, “Marshalling memory: a historiographical biography of Ernest Alexander Cruikshank,” Journal of Canadian Studies (Peterborough, Ont.), 49 (2015), no.3: 23–54. P. W. Lackenbauer, “The military and ‘mob rule’: the CEF riots in Calgary, February 1916,” Canadian Military Hist. (Waterloo, Ont.), 10 (2001), no.1: 31–42. W. D. McConnell, “E. A. Cruikshank: his life and work” (ma thesis, Univ. of Toronto, 1965). Y. Y. J. Pelletier, “The politics of selection: the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada and the imperial commemoration of Canadian history, 1919–1950,” CHA, Journal, 17 (2006), no.1: 125–50. C. J. Taylor, Negotiating the past: the making of Canada’s national historic parks and sites (Montreal and Kingston, Ont., 1990).

Cite This Article

Mark Osborne Humphries, “CRUIKSHANK, ERNEST ALEXANDER,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 4, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/cruikshank_ernest_alexander_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/cruikshank_ernest_alexander_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Mark Osborne Humphries |

| Title of Article: | CRUIKSHANK, ERNEST ALEXANDER |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2024 |

| Year of revision: | 2024 |

| Access Date: | March 4, 2026 |