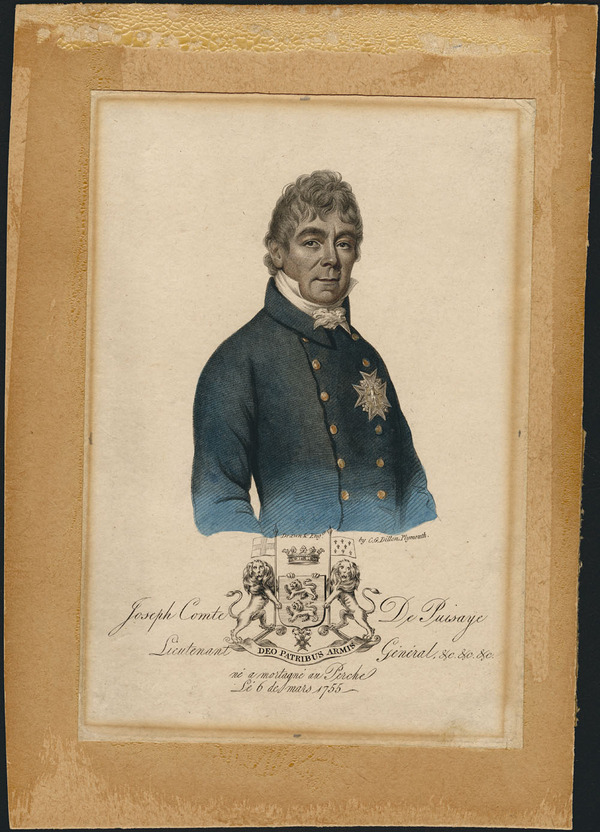

PUISAYE, JOSEPH-GENEVIÈVE DE, Comte de PUISAYE, Marquis de BRÉCOURT, Marquis de MÉNILLES, colonizer and author; b. 6 March 1755 in Mortagne-au-Perche, France, son of André-Louis-Charles de Puisaye, Marquis de La Coudrelle, a high judicial officer, and Marthe-Françoise Bibron (Biberon) de Corméry; d. 13 Dec. 1827 near Hammersmith (London), England.

As a fourth and youngest son, Joseph-Geneviève de Puisaye was destined for the church to preserve the patrimony for his elder brothers and sister. He received the tonsure at the age of seven. Educated by a tutor until he was nine, he was then sent to the Collège de Laval, the Collège de Sées, and the Séminaire de Saint-Sulpice in Paris. The seminary’s superior saw that this 17-year-old had no religious vocation and encouraged him to seek a worldly calling.

Following his father and brothers, Puisaye went into the army in 1773, but it gave him no experience of warfare. Through his maternal grandmother, he obtained a second lieutenant’s commission in a cavalry regiment on the German frontier in February 1775. Since the regiment was at reduced strength, he was free to read and travel. He was summoned from this indolent life when his grandmother obtained the promise of a dragoon company for him. He did become a supernumerary captain in the Régiment de Lanan in 1779, but the company did not exist. Disillusioned with peace-time soldiering, he retired to Mortagne-au-Perche in 1781–82.

The next five years, he wrote, were “the happiest of my life,” for his birthplace contained “all the delights of an agreeable and select society.” Advised not to resign from the army without the cross of the Order of Saint-Louis, he bought a colonelcy and an honorary position in the king’s household guard to qualify for this award. On 19 June 1788 he married Louise Le Sesne, the sole heir of the Marquis de Ménilles; “this marriage,” he admitted, “put me into possession of a truly fine estate,” at Pacy-sur-Eure in Normandy. Although he had other properties, he divided his time between this estate and Paris. Despite his professed dislike of public affairs, he helped draft the cahier de doléance of the Perche nobility and he was selected in 1789 to represent them in the Estates General. His family had a traditional pre-eminence in that province’s nobility.

Puisaye was surprisingly liberal: he favoured a constitutional monarchy without the destruction of social ranks and allied himself with the Girondins. After the first session of the National Constituent Assembly, he stopped attending and he was not re-elected in 1792. His reformist politics and ambition had allowed him to become commander of the national guard in the Evreux district in 1790. When in 1793 the Jacobins in the National Convention proscribed the Girondins, Puisaye turned against the revolution; this late conversion made other, more conservative, counter-revolutionaries distrust him.

Puisaye was commanding the advance guard of a Norman army of federalists and royalists when it was surprised and scattered in July 1793; his nearby estate was sacked. He escaped to the forest of Pertre in Brittany where he tried to weld the anarchistic Chouans into a disciplined anti-Jacobin army. His ambition was both noble and selfish: to rally all insurgents under his leadership. By chance, he intercepted dispatches from England addressed to leaders of the royalist forces and he-replied to them himself. His proposals so impressed the British government that it supported him with arms and money. As a constitutional monarchist, Puisaye was more acceptable than other French royalists. In another act of bravado, he initiated manifestos calling on the government troops to desert and the population to rebel. To arrange a royalist landing by sea that was to spark a general insurrection, Puisaye went to London in 1794.

His plan failed catastrophically. In June 1795 the Royal Navy landed 6,000 royalist troops at the Baie de Quiberon in southwest Brittany. Recognized by the British as commander, Puisaye found that the French princes had given command of the royalist regiments equipped by Britain to the cautious Comte d’Hervilly. Under a divided leadership, the royalist and Chouan allies did not act decisively. They were soon confined to the narrow Quiberon peninsula and then driven back to the water’s edge. Thousands drowned trying to reach the British ships and those who surrendered were shot. Puisaye had already boarded a ship, ostensibly to save the official correspondence.

The count landed once more in Brittany in September 1795 to unite the remaining Chouans. Their factionalism and willingness to make peace with the republican government caused him to return to England, where he met a hostile and equally divided French community in exile. He was unjustly blamed for the Quiberon disaster and for being a coward. Puisaye believed that only a Bourbon prince’s presence in France could revive the royalist forces there. When he organized a collective appeal to the Comte d’Artois in December 1797 to provide that leadership as promised, a curt refusal was sent back and Puisaye’s resignation as lieutenant-general in the king’s armies was accepted.

Since 1793 there had been proposals to resettle exiled French royalists in the Canadas, where émigré priests had found a refuge [see Philippe-Jean-Louis Desjardins]. One French officer wrote of a common desire “to go and enjoy in Canada a less impure air than that of Europe . . . [and] to add to the number of Great Britain’s faithful subjects.” The British government was intimidated by the cost of aiding a mass migration until Puisaye and his associates presented a scheme that promised repayment of public expenses while converting those who were a burden to public and private charity in England into productive, self-supporting colonists who would help defend British North America. The plan would also “place decided Royalists in a country where Republican principles and Republican customs are become leading features.”

Forty-one persons under Puisaye sailed from England in the summer of 1798 to lead the way for an expected migration of thousands of “French loyalists.” They were to receive the same land grants and aid given to the American loyalists. With Puisaye were Major-General René-Augustin de Chalus, Comte de Chalus; Colonel Jean-Louis de Chalus, Vicomte de Chalus; Colonel Jean-Baptiste Coster, dit Coster de Saint-Victor; Colonel Jean de Beaupoil, Marquis de Saint-Aulaire; and Lieutenant-Colonel Laurent Quetton St George, among others. Most were veterans of the Breton army. When the main party reached Kingston in late October, their final destination in Upper Canada was unknown. The refugees wanted to settle apart from the established French-speaking population. As William Windham, the British secretary at war, explained, “considering themselves as of a purer description than the indiscriminate class of emigrants and being in some measure known to each other, they wish not to be mixed with those whose principles they are less sure of and whose future conduct might bring reproach upon the Colony.” The administrator of Upper Canada, Peter Russell*, chose a site in Markham and Vaughan townships, equidistant from the French-speaking settlements on the Detroit River and in Lower Canada. Fifteen miles north of York (Toronto), the émigrés could be closely supervised and they would protect the little capital from a northern attack while at the same time extending Yonge Street to Lake Simcoe. The exiles were well armed and would have been formed into a regiment, had they been more numerous. Legislative councillor Richard Cartwright* recommended Puisaye as one who “brings with him a large Property” and whose colonists “will be a valuable Accession to the higher & anti-democratical Society of this Province.” Bishop Pierre Denaut* of Quebec hoped that the newcomers would strengthen the position of the Roman Catholic Church in Upper Canada.

Leaving the others in winter quarters at Kingston, Puisaye hurried on to York to confer with officials and he then took soldiers from his party to the designated site to clear the land and build shelters amid the snow. The settlement, near present-day Richmond Hill, was named Windham after the secretary at war who had befriended the émigrés. Eighteen homes were framed by February 1799 and more colonists proceeded to Windham. The hardships, privation, and isolation of pioneer life sapped their morale. They were a costly distance from York and roads were often impassable. Puisaye set off, the colonial government was told in March, to acquire a place at the head of Lake Ontario, near the mouth of “a little river capable of bearing a bateau to reach our establishment.” This was to be an entrepôt for Windham, it was said, but Puisaye failed to obtain a government building at Burlington Beach (Hamilton) for the purpose. He bought an American loyalist’s farm near Niagara (Niagara-on-the-Lake) and negotiated with Joseph Brant [Thayendanegea*] and the Mississauga Ojibwas for a large shoreline tract near Burlington Bay (Hamilton Harbour). Puisaye seemed to be looking for a more accessible and congenial location for the entire colony.

A few of the aristocrats at Kingston and Windham were discontented. They had expected estates upon which others would do the hard work. Of the 25 soldiers and servants brought from England as labourers, two drowned at Quebec and seven deserted. They were replaced by eight adults with a dozen children, hired in Lower Canada. Puisaye was helped by a manservant, a soldier, his young housekeeper Mrs Susanna Smithers, whom he had secretly married in 1797 (his first wife having died two years before), and her brother William Kent. Most of the émigrés could not afford to pay for servants.

A government agent was disturbed by the situation in May 1799. “The Emigrés do not seem to be united; the Gen’l. de Puisay, after having made great exertions in the winter to have Huts erected and Land cleared, has purchased for himself a House near Niagara seemingly intending to provide for himself a settlement and to have his followers to shift for themselves,” reported Isaac Winslow Clarke. Windham was then inhabited by “only the Viscount de Chalus and six other officers with about a dozen Privates,” as well as a score of Canadian servants. Coster de Saint-Victor reproached Puisaye for his promises of collective labour and military appointments for the officers; “not being educated to work the land, it would be impossible for me to obtain my living from it,” he wrote. Saint-Aulaire also felt deceived. “This military unit in which I might find emoluments, these Breton peasants whose arms were to aid me are only a fantastic hope,” he complained to Governor Robert Prescott*. Suspecting the count of maligning him, Saint-Aulaire wrote a long, defamatory memorial about Puisaye and his assumed mistress, Mrs Smithers. These two malcontents, Coster de Saint-Victor and Saint-Aulaire, returned to England. Some of the refugees settled in Lower Canada, a few drifted into commerce, and one shot himself. By June 1802 just sixteen, including two children born in Canada, remained at Windham. The agricultural colony continued to decline over several years and the anticipated influx of French exiles never came, although a few more individuals arrived.

After the spring of 1799 Puisaye lived at Niagara with a few of the emigrants. He still regarded himself as the head of the Windham settlement, where he owned land, and he sent supplies and lent money to the colonists. At Niagara he supervised improvements to his farm, planned a windmill, dabbled in trade, and composed his memoirs. He acquired a second farm and had a house built at York. The British government had already supplied the exiles with transportation, land, seed-grain, farm implements, and rations, yet Puisaye petitioned for a food allowance for his servants and for more land. He claimed that he had spent his own money to establish Windham and, in May 1802, he set out for England to obtain financial restitution, to publish his memoirs, and, possibly, to find some new position of authority. At New York he gave Quetton St George money to buy goods for a shop that the lieutenant-colonel and Captain Ambroise de Farcy were setting up in Puisaye’s farmhouse near Niagara. William Kent later returned to manage the Niagara farm and the count’s other Canadian properties.

From 1803 to 1808 Puisaye published his memoirs in six volumes, based on a voluminous collection of papers now in the British Library. In vindicating his military reputation, he disparaged others, including the Comte d’Avaray, confidant of Louis XVIII. Puisaye was not welcome in France after the restoration of the monarchy in 1814 and did not visit it, even to see his daughter, Joséphine. “I have had a small number of friends,” he wrote, and “a much larger number of enemies.” In 1806 he reported that “I have now retired to the countryside, fifteen miles from the capital [London], in a little cottage that I bought, where I lead almost the same sort of life as at Niagara, amid my chickens and cows – seeing, by chance, a few friends who . . . are sometimes good enough to come and share my solitude.” He did not publicly acknowledge Susanna Smithers as his wife. His explanation in 1816 was that “though we are married those nineteen years, she does not bear my name, as my Circumstances Do not afford the means of Maintening her according [to] her real Rank in Life.” Considering his pride in his own ancestry, it is probable that he was ashamed of her humble origins. Despite his poor health, his pen was always active in writing to friends, in upholding his reputation, in seeking recovery of debts from other émigrés, and in petitioning the government for confirmation of his land grants and for compensation for the use of and damage to his properties during the War of 1812.

When the Gentleman’s Magazine reported his death in 1827 “at Blythe-house, near Hammersmith, after a long and painful illness,” Puisaye was described as “tall, well-formed, and graceful; his face was handsome, . . . and his eyes beamed with intelligence and spirit.” The journal added that he “was well read, brought his knowledge to bear with facility and effect upon any subject, reasoned with force and precision, and spoke with a fluent and polished eloquence, which he often enlivened with flashes of playful or pointed wit.” His persuasiveness, bravery, and energy had served the royalist cause well. Like many of the exiled French aristocracy, he was inordinately jealous of his rank and authority. When his failures and grandiose ambitions brought hostile comments, he became paranoid and used calumny and intrigue to destroy his critics. It was this sort of rivalry and backbiting that undermined French royalist undertakings, whether in France or in Canada.

Joseph-Geneviève de Puisaye is the author of Mémoires du comte Joseph de Puisaye . . . qui pourront servir à l’histoire du parti royaliste françois durant la dernière révolution (6v., Londres, 1803–8); proclamations and other official publications issued in France under his name are listed in the British Museum general catalogue and the Catalogue général des livres imprimés de la Bibliothèque nationale (231v., Paris, 1897–1981).

A chalk portrait of the Comte de Puisaye and a watercolour painting of his home in Niagara are in the John Ross Robertson Canadian Hist. Coll. at the MTL.

AAQ, 20 A, 1: 12–14; 210 A, IV: 10–11, 18–19, 42, 78. ANQ-Q, P-40/8: 476–80; P-289. AO, ms 88, Hamilton to St George, 8 Aug. 1808. Arch. du Ministère des Armées (Paris), Service d’hist. de l’Armée, classement généraux armées royales de l’intérieur concernant le général J.-G. de Puisaye. BL, Add. mss 8075, 104: 1–120 (transcript at PAC). MTL, Laurent Quetton de St George papers; St George papers, sect.ii; D. W. Smith papers, A11: 103–8; B5: 211–12, 221–22; B7: 353–56; B8: 159–60. Niagara North Land Registry Office (St Catharines, Ont.), Niagara Town and Township, abstract index to deeds, 1: 146v–47v. PAC, MG 11, [CO 42] Q, 57, pt.ii: 372–73, 389–408; 140, pt.ii: 393–94; 285: 465; 286: 478; 310: 289–90; 316: 217–22; 321: 172; 324: 423–24; MG 24, A6, letter-books, 1799–1805: 57–58, 89–91, 119, 139–40 (transcripts); RG 1, E14, 8: 579–80; L1, 22: 247, 330–1; 26: 21 (mfm. at AO); L3, 204: 65/52; RG 5, A1: 662–63; RG 8, I (C ser.), 14: 135–36; 77: 130–31; 106: 142–43; 515: 164; 556: 88, 90; 619: 4–151 [This source is invaluable. p.n.m.]; 620: 4–9, 34–62, 66–72, 81–84, 99–106, 109–10, 119–24, 140–41; 744: 39–40; RG 19, E5(a), 3732, claim 21; 3742, claim 173; 3745, claim 369. QUA, Richard Cartwright papers, letter-books, Cartwright introducing Puisaye to D. W. Smith, 4 Nov. 1798 (transcripts at AO). Corr. of Hon. Peter Russell (Cruikshank and Hunter), vols.2–3. “French royalists in Upper Canada,” PAC Report, 1888: 73–87. Gentleman’s Magazine, July–December 1827: 639–40. James Green, “Lettre de James Green au comte de Puisaye,” BRH, 40 (1934): 644. Inventaire des papiers de Léry conservés aux Archives de la province de Québec, P.-G. Roy, édit. (3v., Québec, 1939–40). “Minutes of the Court of General Quarter Sessions of the Peace for the Home District, 13th March, 1800, to 28th December, 1811,” AO Report, 1932: 3–4.

Caron, “Inv. de la corr. de Mgr Denaut,” ANQ Rapport, 1931–32: 153–54, 157, 161, 181; “Inv. de la corr. de Mgr Plessis,” ANQ Rapport, 1927–28: 218. Landmarks of Canada; what art has done for Canadian history . . . (2v., Toronto, 1917–21; repr. in 1v., 1967), nos.1214–15, 1305. Dionne, Les ecclésiastiques et les royalistes français. Maurice Hutt, Chouannerie and counter-revolution: Puisaye, the princes, and the British government in the 1790s (2v., Cambridge, Eng., and New York, 1983). L. E. Textor, A colony of émigrés in Canada, 1798–1816 ([Toronto, 1905]). Vendéens et chouans (2v., Paris, 1980–81). Janet Carnochan, “The Count de Puisaye: a forgotten page of Canadian history,” Niagara Hist. Soc., [Pub.], no.15 (2nd ed., 1913): 23–40. [A. J. Dooner, named] Brother Alfred, “The Windham or ‘Oak Ridges’ settlement of French royalist refugees in York County, Upper Canada, 1798,” CCHA Report, 7 (1939–40): 11–26. Mrs Balmer [E. S.] Neilly, “The colony of French émigrés in York County, Ontario – 1798,” Women’s Canadian Hist. Soc. of Toronto, Trans., no.25 (1924–25): 11–30. G. C. Patterson, “Land settlement in Upper Canada, 1783–1840,” AO Report, 1920. P.-G. Roy, “Le nom Vallière de Saint-Réal était-il authentique?” BRH, 29 (1923): 164–67. Télesphore Saint-Pierre, “Le comte Joseph de Puisaye,” BRH, 3 (1897): 146–48. Philippe Siguret, “Le comte de Puisaye . . . : épisode de la chouannerie dans le Perche,” Cahiers percherons (Paris), no.17 (1963): 3–26 [An excellent article. p.n.m.].

Cite This Article

Peter N. Moogk, “PUISAYE, JOSEPH-GENEVIÈVE DE, Comte de PUISAYE, Marquis de BRÉCOURT, Marquis de MÉNILLES,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 6, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 29, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/puisaye_joseph_genevieve_de_6E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/puisaye_joseph_genevieve_de_6E.html |

| Author of Article: | Peter N. Moogk |

| Title of Article: | PUISAYE, JOSEPH-GENEVIÈVE DE, Comte de PUISAYE, Marquis de BRÉCOURT, Marquis de MÉNILLES |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 6 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1987 |

| Access Date: | April 29, 2025 |