Source: Link

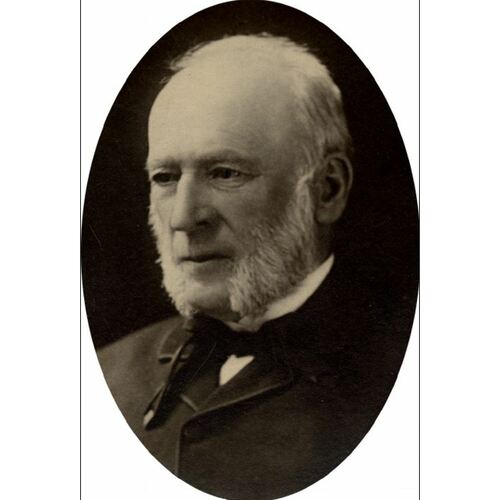

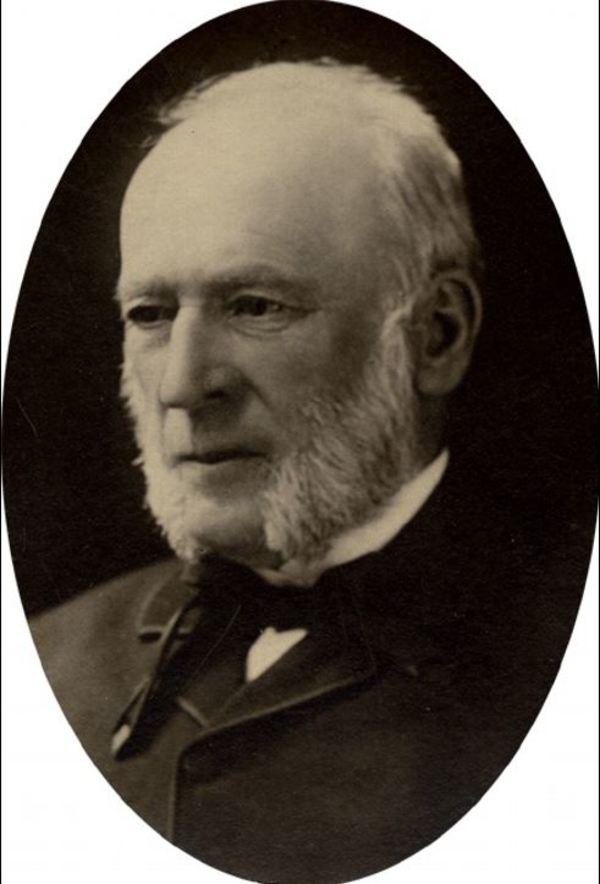

LE MOINE, Sir JAMES MacPHERSON, lawyer, office holder, and author; b. 21 Jan. 1825 at Quebec and baptized 20 February in the Roman Catholic cathedral of Notre-Dame, son of Benjamin Le Moine (Lemoine) and Julia Ann McPherson; m. 5 June 1856 Harriet Mary Atkinson in St Andrew’s Presbyterian Church at Quebec, and they had two daughters; d. 5 Feb. 1912 in Sillery, Que., and was buried 7 February in Mount Hermon Protestant Cemetery following a funeral service in the Roman Catholic church of Saint-Michel.

James MacPherson Le Moine’s mother came from a family of United Empire Loyalists who had settled in the Gaspé and then purchased the seigneury of Île-aux-Grues. His father, who was descended from a seigneurial and bourgeois family connected by marriage to the Dunières, the Trefflés, dit Rottot, and the Woolseys, had served as a militia officer during the War of 1812. He had then taken up a career in business before becoming an office holder. Unlike his son Benjamin-Henri, Benjamin Le Moine would not be involved in politics. But even before 1837 he had become friends with Louis-Joseph Papineau* and later, in the era of the United Province of Canada, with William Lyon Mackenzie*. Keenly interested in history, he was one of a group of old residents of Quebec City including François-Xavier Garneau*, Georges-Barthélemi Faribault*, Philippe-Joseph Aubert* de Gaspé, and several others, who used to meet in Charles Hamel’s store on Rue Saint-Jean [see Aubert]. The Le Moine–McPherson marriage, which took place in the manor-house on Île-aux-Grues, is recorded in the registers of the Anglican Cathedral of the Holy Trinity at Quebec.

For the first few years of his life, James lived on Rue Saint-Georges (Rue Hébert) in Quebec City. When his mother died in 1828, he was sent to his maternal grandparents. He stayed with them in the manor-house and later in Montmagny. At age 13 he moved back with his father to complete his education. He added the patronymic MacPherson to his name at that time as a mark of gratitude to his grandfather. For the next six years he studied at the Petit Séminaire de Québec. After being articled to Joseph-Noël Bossé, he was called to the bar of Lower Canada in March 1850, and he practised law at Quebec until 1858. From then on he devoted himself wholly to his work as collector of inland revenue, an office he had held since 1847, and from 12 Oct. 1869 to 31 Dec. 1899 to his duties as an inspector in the same department. In 1860 he moved to Spencer Grange, a villa set in the heart of a 40-acre estate in Sillery. There Le Moine led a dazzling social life, frequently entertaining prominent Canadians, Europeans, and Americans from the world of letters, politics, or science. Like many Victorians who had re-embraced humanist aspirations, he accumulated knowledge about the past and about nature, which he communicated through his writings.

In approaching Le Moine’s historical work, it must be borne in mind that he came from a pluralistic milieu and that his father had adopted an attitude of tolerance, or even indifference, in matters of religion. Although this background led him to ignore the question of religious belief, it also kept him free of any political commitment based on ethnic antagonism. Confronting the historical past, Le Moine could not consider himself either victor or vanquished. He was both at once. He therefore adopted an ordinary human attitude, knowing that participants in past and present events are most often victims of political decisions made by others. He tried, for instance, to do away with the notion of guilt. In any case he was not interested in ideological disputes. As learned scholars do, he preferred to base his thinking on accumulated data. The more numerous the facts, he believed, the more they would enable him to produce an exhaustive work.

A tireless researcher, Le Moine found his material in public and private archives. He interviewed older people and relied on the good offices of historian friends such as Abbé Louis-Édouard Bois* and Abbé Jean-Baptiste-Antoine Ferland*. Moreover, like today’s archaeologists, anthropologists, and ethnologists, he did field work. From this diversity of sources would come a substantial and varied literary output.

Although Le Moine was interested in the whole period from the European discovery to confederation and although he concerned himself with the political institutions that in succession governed the country, he focused his research on the city of Quebec and its outskirts. So extensive was his knowledge that he could write about both great and small events occurring there, evoke many of the figures who had played even a minor role, and describe the streets, buildings, and landmarks, against the background of the transformations wrought by passing centuries.

Le Moine did not always handle his material in the same way. Sometimes, as in Quebec past and present, he used it chronologically, following the practice of many historians. Sometimes he fitted it around itineraries and journeys, as in his travel guides – Picturesque Quebec, for example. This less rigid approach is ideally suited to the antiquarian, since it allows him to include every detail. He used it also .in accounts of his trips along the shores of the St Lawrence and in the Lac Saint-Jean district, and of his hunting and fishing expeditions in more distant forests. And then there are the seven volumes of Maple leaves, published from 1863 to 1906, which are collections of short articles reflecting all his concerns.

Le Moine was drawn to history, but he did not overlook nature, which constituted the other pole of his writing. From childhood he had been attracted by flora and fauna, and especially by birds. He made observations, collected material, and in 1860 and 1861 brought out his two-volume Ornithologie du Canada. In this work, the first of its kind to be published in French in Canada, he based his nomenclature on the classification system used by Spencer Fullerton Baird of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, who had adopted that of Baron Georges Cuvier. Accepting the model, Le Moine had, however, adapted it, adding to the descriptions of species observations that he had made or that friends had provided. He published numerous other studies on fauna and, fearing that some species might become extinct, he issued warnings and suggested protective legislation.

In one or other of the two languages he had spoken since childhood and had mastered, Le Moine produced a literary output dealing with many subjects and drawing on diverse disciplines. But, like many others, without his penchant for facts he probably would have been forgotten. His pages, so rich in information and eyewitness accounts of all kinds, are still a delight to those interested in the history of Quebec City and its surroundings, or in hunting, fishing, and the great outdoors of the 19th century.

James MacPherson Le Moine received many tokens of respect. He was elected president of a number of associations, such as the Literary and Historical Society of Quebec, and was made an honorary member of a great many Canadian, American, and European societies. In 1882 Governor General Lord Lorne [Campbell] invited him to help draft a constitution for the Royal Society of Canada and to propose a list of potential members. Le Moine was elected president of the French section, and then of the four sections of the society. In 1901 Bishop’s College in Lennoxville conferred on him an lld honoris causa. On 4 Feb. 1897 he received a signal honour for a writer when he was knighted by Queen Victoria.

The following are the best known of Sir James MacPherson Le Moine’s publications: Ornithologie du Canada; quelques groupes d’après la nomenclature du Smithsonian Institution de Washington (2v., Québec, 1860–61); Maple leaves: history, biography, legend, literature, memoirs, etc. (7 ser., Quebec, 1863–1906); Quebec past and present, a history of Quebec, 1608–1876 (Quebec, 1876); and Picturesque Quebec; a sequel to “Quebec past and present” (Montreal, 1882). A complete bibliography of Sir James’s works appears in Roger Le Moine, Un Québécois bien tranquille (Sainte-Foy, Qué., 1985).

AC, Québec, État civil, Catholiques, Saint-Michel (Sillery) [et inhumation dans le cimetière protestant Mount Hermon, Sillery], 7 févr. 1912. ANQ-Q, CE1-1, 20 févr. 1825; CE1-61, 6 sept. 1810, 19 mai 1828; CE1-66, 5 juin 1856. NA, MG 29, D61: 4908–16; D72. J. D. Blackwell, ‘“Borrowed and stolen feathers’: a case of plagiarism in Victorian Quebec,” Épilogue (Halifax), 8 (1993): 33–56. DOLQ, vol.1. Hamel et al., DALFAN. J.-M. Lebel, “Le chevalier de Spencer Grange: l’écrivain et historien James MacPherson Le Moine (1825–1912),” Cap-aux-Diamants (Québec), 1 (1985–86), no.3: 13–17. Roger Le Moine, “La mort de Winceslaus Dupont selon James McPherson Le Moine,” Centre de Recherche en Civilisation Canadienne-Française, Bull. (Ottawa), 16 (avril 1978): 5–11. Edith Le Moyne-White, Le Moyne des Pins: genealogies from 1655 to 1930 . . . (Lévis, Que., 1930).

Cite This Article

Roger Le Moine, “LE MOINE, Sir JAMES MacPHERSON,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 12, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/le_moine_james_macpherson_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/le_moine_james_macpherson_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | Roger Le Moine |

| Title of Article: | LE MOINE, Sir JAMES MacPHERSON |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1998 |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | December 12, 2025 |